VOL. 20

Beyond the Shooting: Eleanor Gray Bumpurs, Identity Erasure, and Family Activism against Police Violence

LaShawn Harris

ABSTRACT

DOWNLOAD

SHARE

During the 1980s, sixty-six-year-old Bronx resident Eleanor Gray Bumpurs maintained that “[Ronald] Reagan and his people had come through the walls” and placed “several cans of human excrement” in her bathroom.”1 Evidence of Bumpurs’s episodic delusions were substantiated during a thirty-minute home visit with a psychiatrist on October 25, 1984. Dr. Robert John, a psychiatric consultant for the Department of Social Services, along with a New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) employee interviewed Bumpurs, inquiring about her failure to pay the over $80 monthly rent on her 31=2 bedroom apartment in the Sedgwick Houses. Drawing on urban working-class families’ historic participation in rent strikes and withdrawals, Bumpurs stopped paying rent that summer, citing a need for apartment repairs. Rent nonpayment resulted in several emergency letters to Bumpurs and allegedly to her children and a scheduled eviction. Immediately after the brief meeting, Dr. John handwrote a short report to NYCHA officials, describing Bumpurs as “psychotic. [She] “does not know reality from non-reality. She is unable to manage her affairs properly and needs hospitalization.” John’s report also noted that Bumpurs held a butcher knife as they left the apartment. John did not perceive Bumpurs as a threat to himself or the NYCHA staffer. “I felt that she was holding the knife defensively [“like a security blanket”], and she made no offensive gesture with it, neither did she threaten us verbally. She was not a danger to herself or others.”2 Despite John’s professional assessment of Bumpurs, NYCHA proceeded with the scheduled eviction.

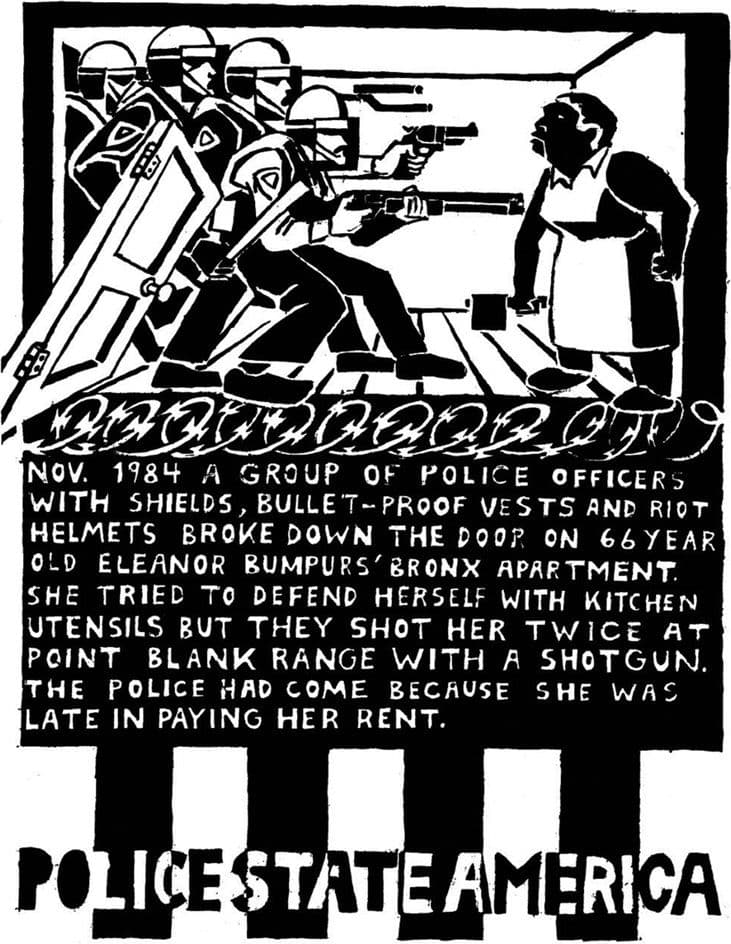

On Monday, October 29, sometime after 9:50 a.m., the Emergency Service Unit (ESU) and Housing Authority police of the New York Police Department (NYPD), the City Marshall, NYCHA workers, Emergency Medical Services technicians, several moving men, and a Department of Social Services caseworker stood outside Bumpurs’s fourth-floor apartment. NYCHA officials were at the apartment to evict Bumpurs and relocate her to a medical facility.3 They even arranged for a moving company to remove Bumpurs’s property from the apartment. The NYPD was on the scene in anticipation of violent resistance from Bumpurs. NYCHA informed police officers that Bumpurs was over 300 pounds, an emotionally disturbed person, and that she had “menaced maintenance men and others with a knife.” Someone in the eviction group also made the unsubstantiated claim that Bumpurs had a history of threatening and throwing lye on strangers. Projections of a chemical-throwing, deranged, and immensely strong Bumpurs erased her identity as a mother and grandmother who was loved by her family; as a scared and elderly woman in need of protection, compassion, and perhaps psychiatric care; and as a poor person who possessed the right to defend and protect their body and property.4 Such allegations and constructed identities forever changed Bumpurs’s life, making her susceptible to violent and inhumane treatment and punishment.5 Imagined constructions also weaponized the silver-haired woman; Bumpurs became a symbol of urban decay and danger, as well as everything that was socially, economically, and morally wrong with New York City. Believing Bumpurs was lethal, six heavily armed ESU officers forcefully entered the apartment. Officers carried plastic shields, a six-foot restraining bar, protective and bulletproof vests, gas masks, and a sawed-off twelve-gauge pump-action shotgun. Once in the apartment, ESU cops observed Bumpurs holding an “eight- to ten-inch butcher knife.” The apartment confrontation between Bumpurs and police officers is highly disputed and only lasted seconds. What is evident is that nineteen-year police veteran and ESU officer Stephen Sullivan, armed with the shotgun, fired two shots at Bumpurs. She was struck in her right hand, blowing off her thumb and index finger, and in the chest (Figure 1). At 10:50 a.m., a medical unit removed a critically wounded Bumpurs from her home. She was taken to Lincoln Hospital in the Bronx and pronounced dead around 11:35 a.m.6 Bumpurs’s killing was symbolic of an expanding carceral state and police power as well as the aggressive policing and management of public and private spaces. Moreover, the tragic apartment killing of a mentally ill and elderly woman illuminated how domestic spaces, entities once called “home,” became (and continue to be) contested terrains between black women and police. And for many New York women such spaces were sites of death.

Figure 1 “Eleanor Bumpurs & New York City Police Officers, October 29, 1984.” Drawing by Seth Tobocman, originally published in Peter Kuper and Seth Tobocman, World War 3 Illustrated: 1979–2014 (Oakland, CA: PM Press, 2014), 134. Image courtesy of Seth Tobocman.

Eleanor Bumpurs’s tragic killing is memorialized in African American literature and political and popular culture. In her 1985 Florida State University lecture, former Black Power activist Angela Davis called her audience to “defend the memory of Eleanor Bumpurs, the 67 year old Black women from the Bronx who was murdered in 1984 by New York Housing Authority policemen because she dared resist an attempted eviction.”7 Disturbed and saddened by Bumpurs’s death, feminist writer Audre Lorde authored “For The Record, In Memory of Eleanor Bumpers” in 1986.8 That same year, Brooklyn filmmaker Spike Lee referenced Bumpurs’s death and her killer’s not-guilty verdict in his black-and-white drama She’s Gotta Have It. Three years later, Lee dedicated his provocative Oscar Nominated film Do the Right Thing, a film centered on 1980s black life and culture in New York City, to Bumpurs and other black and Hispanic New Yorkers who were killed by the NYPD. Likewise, 1980s Hip Hop artists such as Black Star and GhostFace Killah wrote rap lyrics about Bumpurs’s death. More recently, scholars, writers, and political activists of the BLACK LIVES MATTER and #SAYHERNAME movements continue to recall Bumpurs’s killing, situating her death within historical and contemporary conversations about police violence against unarmed black and brown men, women, and children. In 2015, a racial and ethnically diverse group of young New York activists gathered at 1551 University Avenue, the building where Bumpurs lived and died, and staged a protest demonstration against her killing. Chanting “Black Lives Matter” and “Killing Cops Broke Down Her Door; We’re Doing This For Eleanor,” activists, those born well after 1984, gathered to advocate for legal justice for Bumpurs.

Bumpurs is buried under a sea of anti-police brutality placards, lost in the chants of “Black Lives Matter,” trapped in historical inaccuracies, and visually confined to a somber-looking 1980s newspaper photograph. Varying societal constructions of Bumpurs present narrow and troubling interpretations about her life. Bumpurs is etched in public memory as a sickly and overweight and violent person who suffered from mental illness. At the same time, she is viewed as a police-shooting victim, symbolizing a powerful and painful parable about systematic police violence against nonwhite citizens, especially African American women and girls like Californian Eula Love and Bronx resident Alberta Spruill. Heartfelt tributes and popular culture and scholarly accounts on Bumpurs chiefly speak, and at times inaccurately, to the last moments of her life, the way she perished, and the impact of her death on 1980s NYPD policies, New York City politics, and New Yorkers’ long-standing campaigns against police brutality. Somewhat lost in the fight for legal justice for the mother of seven and grandmother of ten was and continues to be her identity. Preoccupied, and understandably so, with the fight against state-sanctioned violence, political activists, scholars, and cultural producers, all who courageously #SAYHERNAME, have failed to go beyond one particular and horrific moment in Bumpurs’s life: her death. Concentration on Bumpurs’s violent slaying freezes her in time, confining her solely to events that occurred on October 29, 1984. Such a narrow lens limits Bumpurs’s socioeconomic and political experiences and possibilities, erases her identity, and fails, according to her daughter Mary Bumpurs, “to keep her [memory] moving.”

Eleanor Bumpurs was more than a police-shooting victim. She was more than a newspaper headline. Bumpurs was a complex individual who lived a complicated life. Her life entailed moments of happiness and joy as well as periods of trauma and disappointment and unfulfilled desires. Media interviews with family and close friends described Bumpurs as a loving and protective mother and neighbor, and as someone who adhered and refashioned normative ideas about female respectability. In a 1984 interview with the Sun City, a black-owned Brooklyn newspaper, Victor Garcia, one of Bumpurs’s neighbors and an eyewitness to the failed eviction, described Bumpurs as a sickly yet nurturing woman who loved children. “She took care of my child, for almost year. But she had to give it up because she was getting to sick. She loved my son. She used to call him Peanut and he used to call her Grandma.”9 At the same time, newspapers, citing from confidential mental health records and neighborhood interviews, deemed Bumpurs a danger to strangers, her family, and even herself.

This article recovers the life of Bronx resident Eleanor Bumpurs from historical obscurity, moving beyond her tragic death and departing from disability and legal studies that primarily focus on her killing, her health and mental issues, and NYPD officer Stephen Sullivan’s 1987 bench trial.10 It attaches a personal narrative to one of New York City’s most recognized yet understudied police brutality cases of the 1980s. Employing a variety of available primary sources including newspapers, photographic images, legal documents, city records, oral histories, and radio and news broadcasts, and reading against and beyond what scholars such as Saidya Hartman and Sarah Haley view as archival grains of death and destruction, I explore Bumpurs’s life prior to her death, situating her within early 20th-century Jim Crow North Carolina and post–World War II New York City.11 Snapshots of Bumpurs’s less familiar life as a southerner and urban migrant reveals her socioeconomic struggles and vulnerabilities, her encounters with carceral institutions, and her pleasure politics. The visibility of Bumpurs’s interior world restores her humanity, transcending the widely accepted police shooting victim image and challenging the “knife-wielding” madwoman caricature. Moreover, Bumpurs’s story is an entry point into the different ways varying socioeconomic and political structures and institutions, those deeply rooted in race, gender, and class oppression left African American women vulnerable to the vagaries of state violence.

Equally important, this work touches on another lesser-known aspect of Eleanor Bumpurs’s important narrative: the community activism of her daughter Mary Bumpurs. Like many 20th-century lynching victims, Eleanor Bumpurs and other police-shooting victims “were isolated from their kin in the last moments of their lives and in the histories written about them.”12 This article addresses that issue, illuminating how Mary Bumpurs was politically transformed by her mother’s death. When her mother died, a community activist was born. To borrow from civil rights activist Mamie Till-Mobley, the mother of 1955 lynching victim Emmett Till, Mary Bumpurs “took privacy grief and turned it into a public issue.”13 While grieving the death of her mother, the unemployed and single mother of three took part in local and national movements birthed out of collective and personal experiences with police violence. Mary Bumpurs was a fierce community advocate. She publicly refuted what the Bumpurs family considered to be falsehoods about their mother; she spoke at various political events with established city politicians, community activists, and other New Yorkers who lost family members to police violence; and she criticized the NYPD and city officials for failing to address police violence against urban citizens. Mary Bumpurs was part of an emerging cohort of 1980s urban leaders, and her activism was rooted in working-class black women’s historic fight against police brutality and urban inequality. Mary Bumpurs’s political efforts were inspired by a desire to radically transform and improve New Yorkers’ quality of life.

Figure 2 Eleanor Bumpurs family picture. Image courtesy of Mary Bumpurs.

The Life of Eleanor Bumpurs

One month after her death a photograph of a smiling Eleanor Bumpurs appeared in The New York Daily News (Figure 2). According to one of Bumpurs’s daughters, the picture was taken at a New York photography studio sometime in the 1950s or 1960s. Also in the original photo but cropped out was Bumpurs’s younger brother Raymond Williams. That day the siblings took several professional photos. Eleanor Bumpurs was happy that day. She was with family; she was excited about getting dressed up; and conceivably, on that day, the burdens of motherhood, romantic loss, economic survival, physical illness, and the emotional scars from childhood trauma were far from her mind. The only thing that mattered that day was spending time with Raymond. This photograph is telling. It points to a happier moment in Bumpurs’s life and raises important inquiries about her life prior to her fatal encounter with the NYPD.

Extant primary evidence complicates efforts at piecing together Eleanor Bumpurs’s family background. Surviving documentation suggests that Bumpurs was born Elna Gray Williams on August 22, 1918, in Louisburg, North Carolina. Her parents were John Williams (Williamson), a sawmill laborer and Fannie Belle Egerton Williams (Williamson), a domestic worker. Married in December 1901, the Williamses had at least six children. Eleanor was the only daughter.14 Coming of age in the Jim Crow South, Bumpurs witnessed and experienced firsthand the harsh realities of racial segregation and white supremacy. At an October 1985 political event in Harlem, featured speaker Mary Bumpurs recounted her mother’s horrific memories of white violence. “My mother told me a story, when I was about 13 years of age, about the experience that she had with the Ku Klux Klan. She saw homes burnt down by these men in white sheets. She saw these homes being burnt, she saw black people being taken in the woods and beaten to death.”15 North Carolina was cloaked in a system of de jure and de facto laws designed to exclude southern blacks from American public life. Black Carolinians like the Williams family were subjected to limited and inadequate education, discriminatory labor practices, political disenfranchisement, sexual assault, and violent encounters with white domestic terrorist organizations.

Family tragedy further complicated Bumpurs’s life. At the age of nine, Bumpurs lost one of the most important persons in her life: her mother. In November 1929, forty-four-year-old Fannie Williams died of pellagra.16 Several days before her own death in 1984, Bumpurs, during a home visit with a NYCHA mental health consultant, briefly mentioned her mother’s death. When asked about her family background, she simply stated “my mother died when I was nine.” Bumpurs offered no additional information about her mother’s death nor did the psychiatric evaluator inquire about how her mother’s death may or may not have impacted her life. Bumpurs’s loss of her mother, especially as the only daughter, was a life-altering experience. Losing her mother meant the “loss of [an] emotional caretaker” and possible long-lasting emotional and behavioral issues.17 After Fannie’s death, widower John Williams and a community of relatives were left to care for several children: seventeen-year-old laborer James Williams, ten-year-old Elma G. Williams, and one-year-old Raymond Williams. Even with the assistance of extended family, economic necessity compelled a grief-stricken John Williams to withdraw Bumpurs from school.18 It was common for working-poor southern families to forego their children’s educational pursuits to supplement household income and ensure family survival. As a child, Bumpurs likely labored as a care worker within her home, cooking and cleaning for her father and brothers. One of her primary responsibilities was tending to baby brother Raymond, who affectionately referred to her as “Satta.”19 Household obligations and economic instability warped Bumpurs’s timeline of maturity, forcing her to relinquish girlhood and quickly transition into adulthood. As a child moving into womanhood, she was expected to be self-sufficient, to put others before herself, and to think and act like a mature adult. More importantly, Bumpurs, while grieving the death of her mother and coping with the rigors of care work, was expected to be a survivor—a trait she constantly drew on during difficult times in her adult life.

In 1942, Bumpurs experienced another life-defining moment. In May of that year, a twenty-five-year-old Bumpurs, who labored as a domestic worker at a white-owned Louisburg hotel, was convicted of assault with a deadly weapon in Franklin county.20 Bumpurs’s criminal background was revealed in a memo from NYPD Commissioner Benjamin Ward, the NYPD’s first and only African American police commissioner, to New York City Mayor Edward Koch in November 1984. Ward informed Koch and later the media that: “a routine run of fingerprints turned up that in 1942 she served 8 months in [the State Women’s prison] in Raleigh N. C.”21 Ward’s memo did not reveal the details of Bumpurs’s arrest. Additionally, the circumstances surrounding Bumpurs’s offense are unknown due to legal restrictions on North Carolina inmate records.22 Conceivably, her crime was precipitated by a need to protect herself or a loved one or by the desire to maliciously do harm to another person. Whatever the criminal circumstances, Bumpurs’s confinement disrupted her home life, which at the time consisted of her husband, Earnest Hayes, and her young daughter Fannie Mae Hayes. After Bumpurs’s conviction, her husband, a former Works Project Administration laborer, was left to shoulder the economic burden of his wife’s absence and to raise their child.23 Seemingly, the couple’s relationship did not withstand Bumpurs’s time in jail. The couple separated before or during her jail stint or shortly after her 1943 release. Moreover, imprisonment separated Bumpurs from the most precious person in her life: her daughter. Separation from Fannie Mae was hard for Bumpurs. She understood firsthand the painful void left by a mother’s absence. Imprisonment hindered her ability to care for her daughter. Like many incarcerated mothers, she worried about her daughter’s day-to-day well-being and adjustment without her and probably wondered if her daughter would remember her after the passage of so much time. Presumably, the imprisoned mother also daydreamed about family reunification and freedom.

Prison release brought new possibilities for Bumpurs. She envisioned a new life for herself and her daughter. The Louisburg native yearned to leave her hometown, a space symbolic of racial and gender exclusion, painful childhood memories, and fractured domestic relationships. Migratory dreams also offered the chance to escape her criminal past. Embodying blues singer Bessie Smith’s 1924 “Woman’s Trouble Blues,” a song about migration, isolation, and imprisonment, and representative of what scholar Sarah Haley calls sonic carceral sabotage, Bumpurs imagined, perhaps while in captivity, “when I get out [of jail]. I’m gonna leave this town.”24 And she did leave Louisburg, never to return. Between 1943 and 1945 Bumpurs and her daughter migrated to New York City. A new spouse or partner, “Mr. Bumpurs,” another North Carolinian who would father some of Eleanor’s children, also accompanied the young mother to the bustling city. The couple joined the nearly 5 million black southerners who trekked to urban cities during the Second Great Migration. New York had the largest urban black population in the 1940s. The city’s black population stood at 458,000 and rose to over 700,000 by 1948. World War II–era New York underwent tremendous socioeconomic and political transformations, and Bumpurs likely bore witness to some of those changes. The southern migrant observed and perhaps experienced firsthand a fast-paced city where racial and ethnic minorities’ visions of decent housing, well-paying manufacturing jobs, quality education, and equality were thwarted by race, gender, and class oppression, residential and labor discrimination, school segregation, inadequate city services, and police brutality, which culminated in race riots during the 1940s and 1960s. At the same time, Bumpurs and other New Yorkers observed or read about the different ways a politically engaged African American, Caribbean and Hispanic, and white population vigorously contested the city’s deeply entrenched and pervasive systems of oppression.25 Little is known about Bumpurs’s settlement experiences in mid-20th-century New York. But varying aspects of her New York life reveal a blend of hardship and a profound desire and struggle for happiness. Like the ideals of many African American women of her generation, Bumpurs’s broader vision of happiness was connected to black women’s historic quest for citizenship, decent and fair housing and employment, public health services, neighborhood safety, and the longing to have their humanity recognized and accepted. Experiencing moments of happiness, especially amid encountering urban inequalities and racial violence, were vital to Bumpurs’s and other racially oppressed women’s emotional stability. Imagining Bumpurs’s pleasure politics, to borrow from Robin D. G. Kelley, “strip[s] away the various masks [she and other] African Americans [wore] in their daily struggles to negotiate relationships or contest power in public spaces, and [allows scholars to] search for entry into the private world hidden beyond the public gaze.”26

Bumpurs’s happiness was, in part, rooted in her ability to financially support and protect her family, and a desire to experience emotional and physical pleasure, love, and intimacy. Moreover, ordinary moments with loved ones brought Bumpurs a sense of happiness and perhaps even peace. Residing in several boroughs, including Brooklyn, Manhattan, and the Bronx, she, between 1945 and 1958, entered into several romantic unions, which resulted in the births of five daughters and two sons.27 Bumpurs enjoyed the holidays and birthdays with her children; she loved dancing; she enjoyed listening to her favorite mid-20th-century radio programs such as Mr. & Mrs. North and Stella Dallas; and she loved cooking for her family. The cultural work of cooking was therapeutic for the southerner. Frying fish or chicken, making peach cobbler, and preparing southern dishes and desserts relieved the stresses of parenthood and perhaps were sweet reminders of her family and happier times in North Carolina. Food preparation and consumption allowed Bumpurs to foster family connections, express familial love, and pass down southern black culinary traditions and recipes. For Bumpurs, household rituals such as cooking signified a sense of self-definition and illuminated her many contributions to her family.28 In a 2017 interview, Mary Bumpurs, reminiscing about her mother’s cooking skills, commented that: “we were poor but she always feed her children. Her cooking was so good. No store-bought food. Everything was from scratch. She could make water smell good.”29

Bumpurs’s hopes for happiness were fraught with difficulties. Labor instability, marital and partner separation, and single motherhood muddled Bumpurs’s chance at happiness. Her martial and romantic partnerships dissolved, making her a single parent and part of an increasing national phenomenon among black women. In 1950, African American households headed by women represented 17.6% and 28.3% by 1970.30 Raising and taking care of all seven children perhaps without the financial benefit of a partner, Bumpurs, throughout the 1950s, worked several informal and formal wage domestic service jobs to keep her household afloat. One of those jobs was at Manhattan’s posh Waldorf Astoria Hotel. By the late 1950s, a health scare and emergency medical surgery forced a fortysomething-year-old Bumpurs into early retirement, making it difficult for her to financially care for her family.31 Considered disabled, Bumpurs applied for and received monthly Supplemental Security Income benefits. It is unclear how Bumpurs supported her family or if she applied for and received federal assistance for her young and teenage children. Despite the family’s dire economic circumstance, one daughter commented that her mother “raised us to the best of her ability. Life was not easy for [our] mother who single-handedly made untold sacrifices just to feed and clothes all seven of [us].”32

The 1970s and 1980s, eras marked by fiscal crisis, deindustrialization, massive unemployment, diminishing city services, narcotic epidemics, and the emergence of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, continued to be difficult periods for the Bumpurs family.33 Imaginably, the burdens of poverty and single motherhood circumvented Bumpurs’s efforts at providing for her family. Bumpurs juggled the demands of motherhood, meeting the everyday demands of household management, and keeping her children safe from city crime. The “fear of crime” was “woven into the fabric of city lives.”34 New York City’s crime rate fluctuated between the 1970s and early 1980s, exposing residents to vandalism, prostitution, neighborhood and subway assaults, murder and rape, and public drug use. Police violence was another issue for New Yorkers, especially those of African descent. As 1970s Brooklyn residents, Bumpurs and her children were imaginably troubled by the brutal police beatings and killings of several unarmed black and Hispanic men, women, and children—including fourteen-year-old Brownsville, Brooklyn, resident Claude Reese and sixteen-year-old Canarsie High School student Rita Lloyd.35 During that time, the Bumpurs family had its own encounter with the NYPD. On November 1, 1973, nearly thirty years after her release from a North Carolina prison, an unemployed fifty-five-year-old Bumpurs, along with one of her daughters, was arrested for menacing, possession of a dangerous weapon, and possession of an unregistered rifle. She was arrested in East New York and detained at what would become the infamous and corrupt 75th Brooklyn Police Precinct.36 Bumpurs pled guilty to all charges and was sentenced to a conditional discharge. She served no time in jail. As with her 1942 arrest, the circumstances surrounding the 1973 arrest are not available to the public.

Bumpurs’s legal issues coincided with several visits to psychiatric facilities. Weeks after her death, the New York Daily News ran numerous stories about Bumpurs’s mental health history, “painting a picture of a disturbed woman.” Journalists reported that the elderly woman received eight years of psychiatric treatment in the Bronx Psychiatric Ward including one commitment and at least seven years of referrals to the Bronx’s Lincoln Hospital outpatient mental health clinic. Published accounts claimed that Bumpurs had “a long history of violent behavior including menacing her children with a knife.”37 In October 1976, Bumpurs “started acting bizarrely, took a knife and disappeared for two days. When she reappeared, she stated that she was on a mission to kill [one of her] daughter[s]. She then reportedly slashed her daughter’s hand with the knife and now refuses to admit that the people who brought her to the hospital are members of her family.” Bumpurs was diagnosed with acute psychosis and hospitalized at Bronx Psychiatric Ward for two months. A similar incident allegedly occurred in March 1977. One of Bumpurs’s daughters called the NYPD, claiming that their mother “was walking around with a knife—slashing at the air and threatening [the] children. She almost cut one of her children.” While these particular episodes were documented in Bumpurs’s confidential mental health file, Mary Bumpurs testified during Stephen Sullivan’s 1987 trial that her mother never harmed her family. Referring to one of the 1970s incidents, Mary stated that her older sister Fannie Hayes Baker, who died shortly after her mother in the mid-1980s, concocted the hand-stabbing story to get their mother admitted to the Bronx Psychiatric Hospital as a mental patient. Asked by Stephen Sullivan’s defense lawyer Bruce Smirty: “Your sister lied to get your mother into a hospital?” Mary replied, “Yes to get her helped.”38

Fabrication over Bumpurs’s criminal behavior revealed the family’s deep concern about their mother’s mental health. Moreover, this falsehood underscored her daughters’ desperate attempt at securing medical treatment for their mother. For some working-class and poor New York families, extracting images of criminality, violence, and madness was a strategic way of navigating city and state mental health admission policies and structural barriers that blocked the poor from receiving adequate care. New York psychiatric institutions underwent massive changes during the 1970s. Budget cuts, city officials’ initiatives to reduce mental health patient numbers, and post–World War II medical professionals’ ideas about psychiatric care resulted in the criminalization of mentally ill persons, inadequate mental health conditions and treatment, and the deinstitutionalization of mental health facilities. Consequently, New York mental health hospitals raised admission standards and typically admitted individuals that were severely violent and incapacitated.39 Sweeping procedural changes in mental health care culminated in increased interactions between law enforcers and the mentally ill, as well as the expansion of police power and the carceral state. “As reforms began emptying psychiatric hospitals, the most vulnerable people with mental illness increasingly ended up in prisons and jails” or on New York streets.40 Working poor blacks like the Bumpurs family perhaps understood the challenges poor people faced securing city services, and the difficulties they faced when denied access to medical care. Consequently, many New Yorkers including the Bumpurs children drew on historically rooted anti-black discourse and racist tropes in order to receive assistance from mental health officials.

The Bumpurs children were undoubtedly concerned with their mother’s mental health. They did not, as suggested by some 1980s news reports and contemporary scholarly accounts, “seem to miss her need for professional counseling.”41 In court and media interviews, Mary Bumpurs indicated that she remembered the day her mother informed her about “seeing her dead brothers walking through the walls” during the 1970s.42 The Bumpurs family painfully observed their mother’s shifting moods and behavior, watching, to borrow from Malcolm X’s reflections on his mother’s mental illness, their “anchor giving away.”43 Attending to their mother’s need, the Bumpurs family developed various strategies to support her. They displayed an outpouring of love and compassion and reluctantly admitted her to poorly maintained city hospitals. It is hard to discern whether Eleanor Bumpurs ever received the medical care her children believed she needed. Photographic images of Bumpurs’s Sedgwick Houses apartment and a visit to a mental health facility in the early months of 1984 suggest that she continued to struggle with deciphering “reality from non-reality.” That year, months before her death, Mary Bumpurs took her mother to Lincoln Hospital “after she got into a fight with another daughter.” Eleanor Bumpurs alleged that one of her daughters was “putting some kind of hex on her.”44

In September 1982, sixty-three-year-old Bumpurs moved into 1551 Sedgwick Houses in the Morris Heights section of the Bronx.45 While Bumpurs lived alone, her daughters and grandchildren lived a short distance away. Close proximity to family ensured that Bumpurs could spend time with them or rely on them if she fell ill. At the same time, the Bumpurs children recognized the importance of their mother living alone. They acknowledged the matriarch’s desire for independence and privacy. According to Mary Bumpurs, “she was of age that she didn’t need us to live with her, she could take care of herself.”46

Prior to her move to the Sedgwick Houses, Bumpurs lived for a short time with one of her daughters at the Amsterdam Houses in Manhattan. In 1980, a massive fire in another Bronx apartment forced Bumpurs to move in with her daughter.47 The fire occurred one floor above her second-floor apartment and forced tenants to evacuate the building. Bumpurs lost everything in the fire. The loss of personal property, her independence, and sorrow for those injured in the fire produced moments of sadness, frustration, and anxiety for Bumpurs. Her tremendous grief was captured in a local newspaper photograph. The widely circulated and only public image of Bumpurs, one of a somber looking and lonely elderly woman clothed in a light-colored bath rope, was taken in the aftermath of the fire (Figure 3). This particular image, often used and appropriated for various political agendas with no context, has defined Bumpurs’s identity as well as New Yorkers’ perception of her.

Bumpurs’s time at the Sedgwick Houses was brief, but some residents and neighbors, those who knew her well or occasionally spoke with her, described her as a friendly woman. Sedgwick Houses resident Florence Peaks described Bumpurs as a loner, yet a pleasant neighbor. Peaks observed Bumpurs routinely leaving her apartment “every Monday morning at about 10 [am]. [S]he’d go to the store [to shop and] to cash a bag full of empty bottles.”48 Another Sedgwick Houses tenant, Sandra Garcia, who lived across the hall from Bumpurs, noted her kindness. “She watched my baby while I went to trade school. She was a private person.”49 In the aftermath of the shooting, sixty-four-year-old Helen Lowe described Bumpurs, whom she called “Ma Bumpurs,” as kindhearted and sociable. The two friends frequently conversed over the telephone and socialized in the neighborhood park, smoking cigarettes, eating “vanilla and chocolate popsicles,” and commiserating over their physical ailments. “We used to call each other every day. We talk[ed] about our pain.”50

Figure 3 Eleanor Bumpurs after 1980 Bronx apartment fire. From the New York Daily News, October 30, 1984. Photo by Harry Hamburg/# The Associated Press via AP Images; used with permission.

Because of her declining health Bumpurs spend a considerable amount of time in her well-kept apartment, watching television and observing neighborhood happenings outside her window. Notwithstanding societal post–World World II perceptions of public housing recipients as idle unemployed home keepers residing in poorly maintained apartments, Bumpurs invested in her private space, “creating an attractive [and decorative] space that [she] call[ed] home.”51 Court trial and newspaper images of Bumpurs’s apartment show an orderly space. Her living room consisted of several small couches, two small tables and lamps, a dining table and chair, a wall clock, and several decorative wall statues and a picture of slain civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. Her kitchen was small but stocked with appliances, seasoning salts, and food. Her bedroom was tidy, and her clothes were organized and neatly folded in her dresser. While visiting her mother’s house after the shooting, Deborah Bumpurs, one of Eleanor Bumpurs’s daughters, commented on her mother’s clothes while refuting claims that she was mentally disturbed. “Look at how neatly these clothes are folded. Is that the way an emotionally disturbed person behaves?” Another family member also questioned the mentally disturbed claim, remarking, “how can they say that mammy was mentally disturbed when she kept this apartment so neat?”52

Conversely, Bumpurs’s living space did reveal glimpses of mental instability. A few weeks before Bumpurs’s eviction and death, NYCHA maintenance workers made a startling discovery in her bathroom. Entering the space, they encountered “a lot of … large flies and there was this horrible smell and in the bathtub there were several cans of human excrement.” When asked about the condition of the bathtub, Bumpurs claimed that: “[President Ronald] Reagan and his people had come through the walls and done it.”53 Several other brief conversations with the NYCHA workers underscored Bumpurs’s sense of reality. She claimed that: “her children were killed by [Cuban president Fidel] Castro and Reagan,” [who] also lived in the building” and that her nonpayment of rent was “because people had come through the windows, the walls, and the floors, and had ripped her off.”54 Faulting 1980s U.S. president Ronald Reagan and Communist leader Fidel Castro for the bathroom’s condition as well as for murder and burglary is telling. Even in Bumpurs’s seemingly declining mental state, her comments, particularly about Reagan, were representative of broader critiques on Reaganomics and its impact on the urban poor. Reagan’s economy plan, while giving tax cuts to wealthy corporations, slashed billions of dollars from Medicaid, Supplemental Security Income, Aid to Families with Dependent Children, job-training and food stamps programs, and other social welfare programs designed to serve the poor.55 Underprivileged Americans like Bumpurs viewed Reagan and his administration as villainous politicians who were indifferent to the economic needs of the working poor and unemployed. In a 1984 New Pittsburgh Courier editorial former civil rights leader Bayard Rustin noted that “under the Reagan Administration the poor [has] gotten poorer and the rich richer. The poor has suffered a serious erosion in their standard of living.”56 It is not evident whether or how Reaganomics impacted Bumpurs or her family. Conceivably, she did, however, like many New Yorkers, witness the devastating impact of economic violence on the city’s poorest residents.

“I’m Still without a Mother. [But] I’m Gonna Fight All the Way”: A Daughter’s Campaign for Legal Justice

Eleanor Bumpurs’s killing polarized New York residents, intensifying existing contentious and fragile race relations between varying racial and ethnic groups and among urban citizens and police. A broad interborough coalition of New York activists, including labor union and Communist Party organizers, civil rights and church leaders, prison activists, politicians, and middle and working-class urbanites, associated the 1984 killing with the NYPD’s long history of violence against city blacks and Hispanics, such as the 1970s and 1980s deaths of Arthur Miller, Clifford Glover, and Elizabeth Mangum.57 In a 1986 New York Amsterdam News (NYAN) editorial, one activist commented that: “the murder of Eleanor Bumpurs should not be seen as isolated incident of police murder. It must be seen in the broader context of the economic and political crisis facing African Americans and other minorities.”58 Public outrage over Bumpurs’s death culminated into citywide protests. New Yorkers staged anti–police brutality demonstrations, tenant meetings, and violent protests; organized grassroots groups like the Eleanor Bumpurs Justice Committee (EBJC), and embarked on letter-writing campaigns to city officials and black media outlets. For instance, in January 1987, more than one hundred New York State prison activists at the Attica Correctional Facility sent a petition to Bronx District Attorney Mario Merola. No strangers to political activism or state sanctioned violence, Attica inmates called for “the expeditious, diligent and vigorous prosecution” of Officer Stephen Sullivan. According to prison activist Charles Montgomery (Kenya Nkrumah), the petition symbolized “our outrage and concern over the killing of Eleanor Bumpurs, and to also let the public known that there are people in prison who are concerned about this case and who want to see Stephen Sullivan brought to trial for his unjust killing of Bumpurs.” The petition was also sent to the NYAN and the black-owned radio station WLIB.59 Similarly, in the immediate aftermath of Bumpurs’s killing, Brooklyn’s City Sun newspaper launched “A Petition To Stop Police Brutality and Violence Now.” Printed in several newspaper editions, the petition: “deplore[s] the killing of Mrs. Eleanor Bumpurs at the hands of New York City police officers, and we deplore every other such act that has violated, or that will violate, the fundamental civil rights of our neighbors, families, and friends.”60 Pressuring city politicians and the Bronx’s District Attorney’s office, activists, journalists, and ordinary citizens demanded the arrest of NYPD officer Stephen Sullivan and called for police procedural changes on interacting with mentally and emotionally disturbed persons.

No one pushed harder for legal justice for Eleanor Bumpurs than her daughter Mary Bumpurs. In the wake of her mother’s tragic death, Mary, a thirty-something-year-old unemployed and single Bronx mother, became a community activist in her own right. The death of her mother transformed Mary from an ordinary citizen into a powerful community leader. She became part of a historic and contemporary group of New Yorkers, including Annie Evans, Kadiatou Diallo, and Erica Garner, who became political activists as a result of losing a loved one to police violence.61 Joining an established group of 1980s New York activists, Mary courageously took part in local and national political movements that raised the nation’s consciousness about police brutality and her mother’s death. “Shotguns are for elephant hunting, not for an old woman who was terrified by people breaking into her apartment. I’ve lost something that I’ve had all my life. But even though I’m still without a mother. I’m here, and I’m gonna fight all the way.”62

Mary Bumpurs was a fierce advocate for her mother. As the family spokesperson, she gave radio interviews, was a featured guest at community events, and delivered heartfelt speeches at political rallies with city politicians and local activists. Public and political events were venues for Mary to discuss her mother’s life and connect her killing to New York activists’ broader campaigns against police violence and urban inequality. More importantly, Mary used public appearances to refute racist critiques about her mother, particularly scathing comments that disparaged Bumpurs for being overweight and for receiving public assistance. For instance, some New Yorkers, those who believed NYPD officer Stephen Sullivan justifiably killed Bumpurs, asserted that Bumpurs and her “many” children were “welfare cheat[s].” “Why didn’t her family of seven grown children pay her rent? Why did they let things get so bad; are they on welfare also? She got fat on our tax dollars.”63

The Policemen’s Benevolent Association (PBA) also took part in the postmortem vilification of Eleanor Bumpurs. Under the leadership of PBA president Phil Caruso, the over-10,000-member union opposed the Bronx District Attorney’s indictment of Sullivan and staged one of New York’s largest police protests in February 1985.64 Moreover, the PBA launched a well-orchestrated smear campaign against Bumpurs. Sometime in December 1984, the PBA used radio commercials and newspapers ads to censure Bumpurs, depicting her as a violent woman who endangered the lives of police officers. Rooted in racism, poverty, fatness, and ableism, the PBA’s media campaigns against Bumpurs were weapons of anti-black violence and intended to erase her humanity and lessen public sympathy for her. Paying more than $30,000 for media ads, the PBA attempted “to set the record straight. Our campaign merely attempts to place in perspective the police side of a controversial issue.” Commercials asserted that: “This 300-pound woman suddenly charged one of the officers with a twelve-inch butcher knife, striking his shield with such force that it bent the tip of the steel blade. It was as she was striking again that the shots were fired.”65 Inflammatory references to Bumpurs’s weight signaled to radio and television audiences that she was physically intimidating and capable of positioning her body in a threatening way; therefore, Sullivan had no choice but to use deathly force. The New York Daily News indirectly buttressed the image that Bumpurs was a danger to New York housing personnel, police officers, and anyone who entered her apartment. The newspaper published images of Bumpurs’s household knives, including the twelve-inch knife used to threaten Sullivan and the other officers. Imageries of an overweight knife-wielding woman erased Sullivan’s culpability, and resurrected 20th-century ideas that murdered and physically or sexually assaulted black women were responsible for their own demise.66

Mary presented an alternative image of her mother. In media interviews and at political demonstrations, the second-oldest daughter offered New Yorkers images of a resilient and protective mother who experienced cycles of pain and disappointment. Her testimonials exposed her mother’s veiled vulnerabilities and “clear[ed] up a couple of things” because “in the papers they showed my mother as being psychotic.” The newly minted activist expressed what was not reported in city papers, giving her audience a window into her mother’s life as a working-poor woman and as a single parent. Mary employed what scholar Leigh Raiford identified as critical black memory, “using history for the present” and gave voice to her mother’s “historical silences.”67 Moreover, her public talks rendered visible the emotional toll crime, particularly police violence, had on her family. “For 39 years I didn’t know what death was about, and to lose your mother in that kind of a way, that’s pretty painful. This hurt a lot of us. And it’s not fair. There’s no way they can ever justify it and give us anything, because there’s nothing they could give us back in the place of the what we lost.”68

Figure 4 Mary Bumpurs and Bronx Councilman Wendell Foster. From the photo collection held at the Tamiment Library, New York University, by permission of the Communist Party USA.

Mary Bumpurs’s newfound activist role brought her into contact with prominent city community leaders and politicians. On the one-year anniversary of Bumpurs’s death, the EBJC, an inter-borough grassroots group composed of local activists and Bumpurs’s relatives and friends, organized a commemoration program at Junior High School 82 in the Bronx. In remembrance of Bumpurs, program speakers, such as civil rights attorney C. Vernon Mason and Bronx pastor and City Councilman Wendell Foster, reminded attendees of “The Continued Fight for Justice.”69 An Alabama native and pastor of Christ Church in the Morrisania section of the Bronx, Foster became the first black elected city official in the Bronx in 1978. Foster was one of few city politicians who supported the Bumpurs family. The politically engaged pastor made funeral arrangements at his church for Eleanor Bumpurs, raised funds for the funeral services, and often appeared alongside Mary Bumpurs at citywide protests (Figure 4).70 Mary Bumpurs established a close partnership with another religious leader: Brooklyn Pastor Herbert Daughtry. A longtime city activist, Daughtry was a founding member and the chairman of the Black United Front (BUF), a 1970s political organization that was in the forefront of fighting police brutality. During the 1970s and 1980s, the BUF launched citywide protests against the police killings of fifteen-year-old Randolph Evans, Brooklyn entrepreneur Arthur Miller, and Luis Baez.71 Like Foster, the Brooklyn leader counseled Mary and often appeared with her on radio interviews. For instance, when a Bronx grand jury indicted Sullivan on second-degree manslaughter charges in February 1985, Mary and Daughtry held a press conference at Daughtry’s House of the Lord Church. Both expressed disappointment over the manslaughter charge, which carried a possible fifteen-year prison term. Mary told reporters: “I’m not satisfied. He should be sitting in jail for life. They gave me some justice, but not 100 percent. I was looking for something with a heavier penalty. This is a sign of hope but the jury’s decision is not going to stop me from fighting.”72

Mary Bumpurs also connected with fellow New Yorkers who had lost family members to police violence. After her mother’s killing, she joined a “club no black woman [or man] want[ed] to join.”73 Publicly and privately mourning with families that suffered from comparable tragedies, Mary forged relationships and networks of support and often appeared at protest demonstrations with those families. The Bronx activist frequently attended anti–police brutality demonstrations and speaking engagements with Veronica Perry, the mother of slain teen Edmund Perry. On September 24, 1985, Mary and Perry appeared at the Communist Party’s (CP) Spartacist Forum at Harlem’s Memorial Baptist Church.74 Perry’s college-bound son Edmund was fatally shot by a white plainclothes police officer in June 1985. Seated behind the CP Spartacist Forum’s banner “From Soweto To Harlem: Smash Racist Terror!,” and next to 1985 Spartacist Party mayoral candidate Marjorie Stamberg and Spartacist Party candidate for Manhattan Borough President Ed Kartsen, Bumpurs attentively listened as Perry tearfully discussed her son’s promising yet short life.75 A schoolteacher and community activist, Perry, like Mary, refuted claims that her son was a troubled teen. She lovingly described Edmund as a talented high school senior who attended New Hampshire’s prestigious Phillips Exeter Academy. Mary understood Perry’s pain as well as her feelings of hopelessness. At the same time, both women, despite their profound sorrow, encouraged their audiences “to stand together” against violent cops, whom they likened to the Ku Klux Klan (KKK). “We Will Not Stand for KKK in Blue Uniforms.” 76 Mary’s brief remarks zeroed in on Mayor Edward Koch, criticizing his visit to her apartment on Thanksgiving Day in 1984. She viewed his visit, nearly one month after her mother’s death, as a political maneuver. “He came to my house with his condolences. He came in with a white box. What was in there? Two dozen chocolate chip cookies. I’m suppose to be a fool, don’t understand that he’s sweetening up my mouth so I won’t talk or I won’t fight this thing? So, old Koch brings me two dozen chocolate chip cookies, to let me know that I’m what, a chocolate chip little ‘nigger’? He didn’t sweeten my tongue up enough to stop me from fighting for what was mine.”77

Throughout the mid- to late 1980s, Mary Bumpurs continued to make appearances with Veronica Perry and other relatives of police shooting victims. In October 1986, the Michael Stewart Justice Committee and BUF members organized a candlelight service for police victims and their families. Held at the Daughtry’s House of the Lord Church, the families of Randolph Evans, Michael Stewart, Eleanor Bumpurs, Edmund Perry, and Dennis Groce were presented with houseplants, representing life and growth. Additionally, Mary Bumpurs supported surviving families’ social justice events and political rallies. On April 4, 1986, the Michael Stewart Justice Committee planned a “Day of Absence” and a “March for Justice” on the anniversary of the assassination of Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King. The committee urged “people of goodwill and consciousness” to take a day off from work, school, and shopping and “march for justice in the spirit of Dr. King. We will be marching in the spirit of Dr. King, Nelson Mandela, Mr. Stewart and Eleanor Bumpurs.”78

Mary Bumpurs seemingly retreated from speaking at community and political events, particularly after Stephen Sullivan’s 1987 acquittal. The Bronx mother continued, however, to support New Yorkers’ collective resistance against city inequalities and mounting police violence. Mary Bumpurs reserved much of her energy for settling the ten-million-dollar wrongful death lawsuit against the NYCHA. In 1990, New York City’s first and only African American mayor David Dinkins and the Bumpurs family agreed to what many New Yorkers considered to be a “ridiculously low,” out-of-court settlement of $200,000.79 Mary Bumpurs and other city activists’ fights against police brutality also pressured city politicians and law enforcement officers to revise NYPD procedures on police interaction with mentally and emotionally disturbed persons. Modified NYPD policies, however, hardly stopped the tragic police killings of several unarmed New Yorkers with mental health issues, including Juan Rodriquez (1987), Renato Mercado (1999), Shereese Francis (2012), Deborah Danner (2016), and Saheed Vassell (2018).80 In recent years, an over-seventy-year-old Mary Bumpurs, while hoping to see an end to police violence, is still haunted by her mother’s death. Contemporary police shootings, particularly those occurring in New York, are painful reminders of her family’s loss. In an October 2016 interview with the New York Post, Bumpurs, briefly speaking about the police shooting death of sixty-seven-year-old and mentally ill patient Deborah Danner, commented that she “has never gotten over the outrage of that day. I relive it every time. That’s something that I’ll never get over because that’s something that was taken away from me.”81

Conclusion

On November 4, 1984, family members, friends and neighbors, community leaders, and politically engaged celebrities such as actors Ruby Dee and Ossie Davis crowded into the Bronx’s Gibson Funeral Home to celebrate the life of Eleanor Bumpurs. Journalists and photographers from the New York Daily News, the City Sun, and other local media outlets also assembled in the small one-story brick church. Mourners painfully spoke about the police violence that ended Bumpurs’s life, as well as their commitment to building a grassroots coalition that shined a spotlight on urban inequalities and the increasing police brutality against New York blacks and Hispanics. Actress and activist Ruby Dee hoped that Bumpurs’s “death be a coming together for all of us.” At the same time, loved ones’ heartfelt tributes went far beyond Bumpurs’s final moments alive and the derisive media portrayals that plagued her in death. For the over one hundred funeral attendees, the silver-haired matriarch was more than a victim or symbol of housing inequality, poverty, or police violence. For them, she was a self-sacrificing woman who possessed a compilation of life experiences—all of which failed to capture the public’s imagination. Collectively, relatives and friends reminded the public that the way Bumpurs lived was equally as important as how she died. They voiced her joys and vulnerabilities, her affinity for cooking and family, and her lifelong battle against poverty. “God knows the hard times she had,” stated one minister. Moreover, their testimonies weaved together a powerful narrative that illuminated Bumpurs’s interior world and her humanity.82

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Mary Helen Bumpurs, Reverend Herbert Daughtry, Maria Hammack, Sharita Thompson, Robert Thompson, Pero Dagbovie, Tiffany Gill, Shannon King, Mary Phillips, Kali Gross, Sarah Haley, Ula Taylor, Keona Ervin, David Stein, Dayo Gore, Kellie Carter Jackson, Priscilla Ocen, Prudence Cumberbatch, and Treva Ellison for their insightful feedback and comments.

WORKS CITED

1. Peter Noel, “Group Decries ‘Sham’ Bumpurs Murder Trial,” New York Amsterdam News, January 31, 1987, 10.

2. “The People of the State of New York against Stephen Sullivan,” New York Court of Appeals Records and Brief, 68 NY2D 495, Appellants Appendix, part 4 (Bronx County Indictment No. 394/1985), 820, https://books.google.com/books?id¼_u9Mi3ZDHXMC (accessed February 22, 2017).

3. “Victor Botnick to Edward Koch,” November 9, 1984, box 0000033, folder 21, Edward Koch Papers (La Guardia and Wagner Archives, La Guardia Community College).

4. Anna Mollow “Unvictimizable: Toward a Fat Black Disability Studies,” African American Review, 50, no. 2 (Summer 2017): 105–21.

5. Camille Nelson, “Racializing Disability, Disabling Race: Policing Race and Mental Status,” Berkley Journal of Criminal Law 15, no. 1 (2010): 13–17; Andrea J. Ritchie, Invisible No More: Police Violence against Black Women and Women of Color (New York: Beacon Press, 2017), 91.

6. Stuart Marques, “Tracking the Tragedy,” New York Daily News, February 1, 1985, 5; “The People of the State of New York against Stephen Sullivan,” New York Court of Appeals Records and Brief, 68 NY2D 495, appellants appendix, part 4; “Memo From Police Commissioner Ward,” City Sun, November 29–December 4, 1984, 5–6.

7. Angela Y. Davis, Violence against Women and the Ongoing Challenge to Racism (Latham, NY: Kitchen Table/Women of Color Press, 1985), 12.

8. Audre Lorde, The Collected Poems of Audre Lorde (Latham, NY: Kitchen Table/Women of Color Press, 1986), 411.

9. “Eyewitness: ‘It Was Like A War,’” City Sun, November 7–13, 1984, 7.

10. Bench trial is a jury by judge. Stephen Sullivan’s trial opened on January 12, 1987, and closed in February 1987.

11. Saidiya Hartman, Lose Your Mother: A Journey along the Atlantic Slave Route (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2008), 17; Sarah Haley, No Mercy Here: Gender, Punishment, and the Making of Jim Crow Modernity (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2016), 14.

12. Kidada E. Williams, “Regarding the Aftermaths of Lynching,” Journal of American History 101, no. 3 (2014): 856.

13. Mamie Till-Mobley and Christopher Benson, Death of Innocence: The Story of the Hate Crime that Changed America (New York: Random Publishing Group, 2011).

14. “Elna Gray Williams,” Register of Deeds, North Carolina Birth Indexes, North Carolina State Archives; “Marriages,” North Carolina County Registers of Deeds, microfilm, Record Group 048 (North Carolina State Archives, Raleigh, NC), available at Ancestry.com.

15. “Mary Bumpurs: “They’re Not Going to Get Away with What They Did,” Workers Vanguard, October 4, 1985, p. 7.

16. Karen Kruse Thomas, Deluxe Jim Crow: Civil Rights and American Health Policy, 1935–1954 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2011), 12–13; “Fannie Bell Williamson,” certificate of death #162 (November 1929) (microfilm: rolls 19-242, 280, 1040–1297) (North Carolina State Archives).

17. Hope Edelman, Motherless Daughters: The Legacy of Loss (Boston: Da Capo Press, 2014).

18. Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930 (Washington, DC: National Archives and Records Administration, 1931); Robert A. Margo, Race and Schooling in the South, 1880–1950 (Chicago: 1994), 10–11.

19. Mary Bumpurs, unrecorded interview by LaShawn Harris, July 27 and August 3, 2017, New York, NY.

20. “Wilborn and Boyd 8 Months,” Franklin (NC) Times, May 8, 1942, 1.

21. “Racism is ‘American as Apple Pie’: Ward” New York Daily News, November 17, 1984, 2.

22. State of North Carolina, Department of Correction, Division of Prisons, “Policy and Procedures,” November 14, 2011, 1–2, http://www.doc.state.nc.us/dop/policy_procedure_ manual/d0600.pdf (accessed March 15, 2017).

23. “Earnest Hayes,” U. S. WWII Draft Cards, Young Men, 1940–1947, available at Ancestry.com (accessed March 15, 2017); “Elenor Gray Williamson,” Social Security Applications and Claims, 1936–2007, 28b, 1940 United States Census, Louisburg, Franklin, North Carolina, enumeration district 35–25 (microfilm; roll M-t0627-02912), available at Ancestry.com.

24. Haley, No Mercy Here, 216, 219–20.

25. Martha Biondi, To Stand and Fight: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Postwar New York (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009).

26. Robin D. G. Kelley, Race Rebels: Culture, Politics, and The Black Working Class (New York: Free Press 1994), 36.

27. “Mary Bumpers,” birth certificate 28091, New York, NY, birth index, available at Ancestry.com; “Deborah Bumpurs,” birth certificate 16826, New York, NY, birth index, available at Ancestry.com; “Keenie Bumpurs,” birth certificate 39039, New York, NY, birth index, available at Ancestry.com; “Terry Bumpurs,” birth certificate 44229, New York, NY, birth index, available at Ancestry.com. I was unable to locate vital statistics for Bumpurs’stwo sons.

28. Psyche Williams-Forson, Building Houses out of Chicken Legs: Black Women, Food, and Power (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 110, 113.

29. Bumpurs interview.

30. Jacqueline Jones, Labor of Love, Labor of Sorrow: Black Women, Work and the Family, Slavery to the Present (New York: Basic Books, 1985), 305–06.

31. Bumpurs interview.

32. Ibid.; Bumpurs, “They’re Not Going to Get away with What They Did,” 7.

33. Alex S. Vitale, City of Disorder: How the Quality of Life Campaign Transformed New York Politics (New York: New York University Press, 2008); Themis Chronopoulos and Jonathan Soffer, “After the Urban Crisis: New York and The Rise of Inequality,” Journal of Urban History, 43, no. 6 (2017).

34. Vitale, City of Disorder, 126.

35. Mary Breasted, “Grand Jury to Get Report on Police Killing of Boy,” New York Times, September 17, 1974, 1; “‘Defensive’ Police Shots Kill a Girl, 16,” New York Times, January 28, 1973, 13.

36. “Eleanor Bumpurs,” Arrest and Complaint Report, Case # 526303 (November 1, 1973) Police Department Legal Bureau—FOIL Unit (New York City Police Department, New York, NY). The City of New York.

37. Suzanne Golubski and David Medina, “Bumpurs’ Past was Violent One,” New York Daily News, December 1, 1984, 4; “Anatomy of A Tragedy: A Troubled History,” New York Daily News, December 2, 1984, 19.

38. Frank Prial, “Daughter Cites Bumpurs’s Stay in State Hospital,” New York Times, January 28, 1987, B6.

39. Jonathan Soffer, Ed Koch and The Rebuilding of New York City (New York: Columbia University Press, 2010), 280–81, 291, 296.

40. Julilly Kohler-Hausmann, “Guns and Butter: The Welfare State, the Carceral State, and the Politics of Exclusion in the Postwar United States,” Journal of American History 102, no. 1 (June 2015): 91.

41. Christopher LeBron, The Making of Black Lives Matters: A Brief History of An Idea (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), 68.

42. “Bumpurs Kin Lied to Hospitalize Her,” New York Post, January 26, 1987, 4.

43. Malcolm X, The Autobiography of Malcolm X (New York: Random House Publishing Group, 2015), 23.

44. Golubski and Medina, “Bumpurs’ Past was Violent One.”

45. “Housing Authority Application,” box 0000033, folder 21, Edward I. Koch Collection (LaGuardia and Wagner Archives, LaGuardia Community College, New York, NY).

46. Bumpurs: “They’re Not Going to Get away with What They Did,” 7.

47. “Housing Authority Application,” box 0000033, folder 21, Koch Collection.

48. David Medina, “Says Bumpurs Could’ve Been Locked Outside,” New York Daily News, December 5, 1984, p. 7.

49. Jimmy Breslin, “Shot Down Like A Lynx,” New York Daily News, November 4, 1984, 3, 8.

50. Jimmy Breslin, “Double-Barreled Double-Talk,” New York Daily News, 8.

51. Lisa Levenstein, “Myth #11: “Tenants Did Not Invest in Public Housing,” in Public Housing Myths: Perception, Reality, and Social Policy, ed. Fritz Umbacj and Lawrence J. Vale (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2015), 64–90.

52. “David Medina, “Bumpurs’ Kin at Death Apt,” New York Daily News, November 28, 1984, 3; “Find Bumpurs Finger in Apt.,” New York Amsterdam News, December 1, 1984, 1.

53. “The People of the State of New York against Stephen Sullivan,” New York Court of Appeals Records and Brief, 68 NY2D 495, Appellants Appendix, part 1, People v. Sullivan (June 1986), 7, https://books.google.com/books?id¼_u9Mi3ZDHXMC (accessed December 18, 2016).

54. Ibid.

55. John Ehrman and Michael Flamm, Debating the Reagan Presidency (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2002), 50–51.

56. Bayard Rustin, “Three Years Later, the Poor Get Poorer,” New Pittsburgh Courier, September 15, 1984, 4.

57. David Vidal, “Crowd of 100 Gathers Outside Police Station for Protest on Slaying,” New York Times, August 20, 1979, 20; “Flatbush Woman, 35, Slain During Eviction, Had Rent Ultimatum,” New York Times, August 31, 1979.

58. “The Eleanor Bumpurs Case,” New York Amsterdam News, September 20, 1986, 14.

59. Noel, “Group Decries “Sham’ Bumpurs Murder Trial,” 1; “Attica Inmates Demand Justice in Bumpurs’ Slaying,” Daily Challenge, February 12, 1987, 2.

60. “A Petition to Stop Police Brutality and Violence Now,” Brooklyn City Sun, November 7–13, 1984, 11; Wayne Dawkins, City Son: Andrew W. Cooper’s Impact on Modern-Day Brooklyn (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2012).

61. Annie Evans’s son Randolph Evans was shot by police in 1976. In 1999, police officers shot and killed Kadiatou Diallo’s son Amadou Diallo. Pranay Gupte, “2,000 Mourn Randolph Evans at Emotional Funeral,” New York Times, December 1, 1976, 39.

62. Don Singleton, “Bumpurs’ Kin Sue City For 10M,” New York Daily News, December 21, 1984, 8; Anatomy of a Tragedy, New York Daily News, December 2, 1984, 31.

63. “Howard Beach: Black Victim on Trials,” Workers Vanguard, January 23, 1987, 1, 5; Rhonda Williams, The Politics of Public Housing: Black Women’s Struggles against Urban Inequality (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005).

64. Alexander Reid, “Thousands of Officers Protest Indictment of Colleague in Bumpurs Shooting,” New York Times, February 8, 1985, B1.

65. Sol Stern “PBA for The Defense,” Village Voice, January 1, 1985, 15; Phil Caruso, “Why the Police Have Had to Buy Ads,” New York Times, January 9, 1985, A2.

66. Gross, Colored Amazons, 25.

67. Leigh Raiford, Imprisoned in a Luminous Glare: Photography and The African American Freedom Struggle (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011), 62–63.

68. Bumpurs, “They’re Not Going to Get away with What They Did,” 7.

69. “Bumpurs Program,” New York Amsterdam News, October 26, 1985, 35.

70. Katherine Bindley, “Still Dreaming the Dream,” New York Times, February 13, 2009; “Rev. Not the Lord’s Will,” Brooklyn City Sun, November 7–13, 1984, 6.

71. Herbert Daughtry, No Monopoly on Suffering: Blacks and Jews in Crown Heights (Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 1997).

72. Utrice C. Leid, “15 Years Is Not Enough,” Brooklyn City Sun, February 6–12, 1985, 8.

73. Rhon Manigualt-Bryant, “A ‘Club’ No Black Woman Wants to Join: Confronting the Aftermath of Black Death,” Black Perspectives, last modified July 19, 2016, http://www. aaihs.org/confronting-the-aftermath-of-black-death/ (accessed July 22, 2016).

74. Harvey Klehr, Far Left of Center: The American Radical Left Today (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 1988), 71–72.

75. “Vote Spartacist!,” Workers Vanguard, November 1, 1985, 11.

76. Bumpurs: “They’re Not Going to Get Away with What They Did,” 7; Veronica Perry, “We Will Not Stand for KKK in Blue Uniforms,” Workers Vanguard, October 4, 1985, 7.

77. “Koch Visits Kin of Victim in Eviction,” New York Daily News, November 23, 1984, 7.

78. “Stewart Committee Marches for Justice,” New York Amsterdam News, April 5, 1986, 9.

79. J. Zamba Browne, “Outcry over $200,000 Court Settlement in Bumpurs Case,” New York Amsterdam News, April 6, 1991, 4.

80. Andrea Mcardle and Tanya Erzen, Zero Tolerance: Quality of Life and the New Police Brutality in New York City (New York: Fast Track Books, 2001), 74.

81. Stephanie Pagones, “NYPD Shooting of Mentally Ill Woman Invokes Memory of Eleanor Bumpurs,” New York Post,October 20, 2016, http://nypost.com/2016/10/20/nypd-shooting-of mentally-ill-woman-invokes-memory-of-eleanor-bumpurs/ (accessed November 10, 2016).

82. “Rites for Woman Police Killed,” New York Times, November 4, 1984, 53; Rueben Rosario, “Peace, At Last,” New York Daily News, November 4, 1984, 3.

Past Editions

1.

“The most unprotected of all human beings”: Black Girls, State Violence, and the Limits of Protection in Jim Crow Virginia

Lindsey Elizabeth Jones

2.

“We will overcome whatever [it] is the system has become today”: Black Women’s Organizing against Police Violence in New York City in the 1980s

Keisha N. Blain

3.

Beyond the Shooting: Eleanor Gray Bumpurs, Identity Erasure, and Family Activism against Police Violence

LaShawn Harris

4.

Care Cage: Black Women, Political Symbolism, and 1970s Prison Crisis

Sarah Haley

5.

Contested Commitment: Policing Black Female Juvenile Delinquency at Efland Home, 1919–1939

Lauren N. Henley

6.

Policing Black Women’s and Black Girls’ Bodies in the Carceral United States

Kali Nicole Gross

7.

The Aesthetic Insurgency of Sandra Bland’s Afterlife

Phillip Luke Sinitiere