On a gray, cold, and rainy Friday in Seattle, we—Vanessa, Joni, and Gloria, three girlfriends, art educators and Women of Color (WoC)—took a brief detour away from our attendance at the National Art Education Association (NAEA) conference. Our detour took us to visit the highly acclaimed Seattle Art Museum (SAM) exhibition, “Figuring History,” featuring Black American artists Robert Colescott, Jacob Lawrence, and Mickalene Thomas. By the second day of our conference, we were exhausted, tired, and depleted. However, our weary condition was not a result of having presented multiple times about our research and classroom practices. Instead, it was from our perceived need to perform, act, and engage in ways that did not align with our authentic ways of being. As three WoC at a three-day professional conference with predominantly White women, there was a persistent and undeniable truth, communicated both visually and through the conference content: that we, WoC, were in someone else’s space. From being critiqued for our equity-focused research, to even our mode of presentation, we were emotionally fatigued. Engaging with the visual art in “Figuring History”—where Black and Brown bodies were not only celebrated, but also portrayed as vibrantly multidimensional—was not only desired but necessary for us.

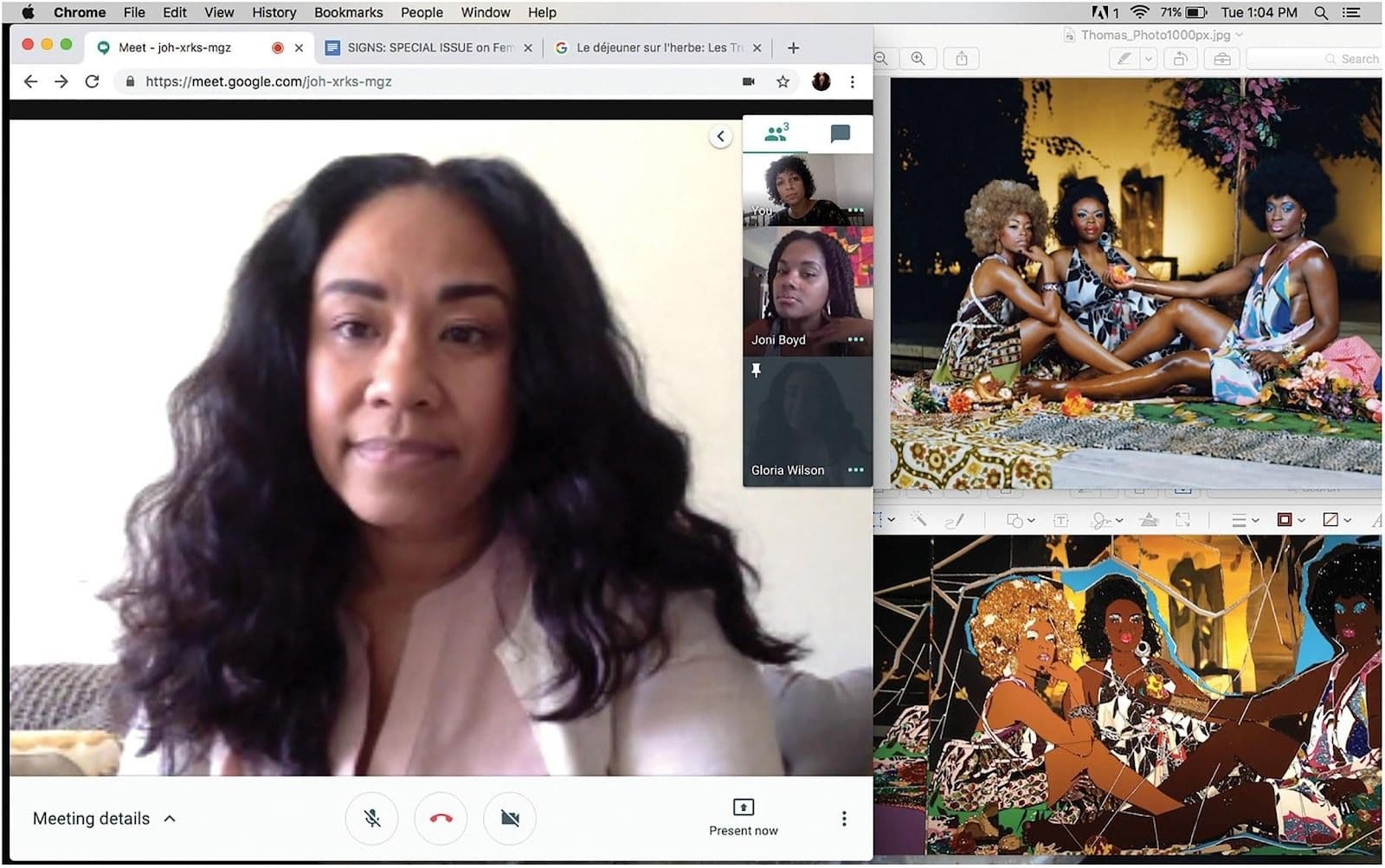

After about an hour of walking through the exhibition, we approached the artwork of Mickalene Thomas, a Black, queer woman. We were immediately overwhelmed by the enlarged, textured faces of three multitoned Black women looking back at us like a mirror. The Black women in Mickalene Thomas’s work titled “Le d,ejeuner sur l’herbe: Les trois femmes noires” (translated loosely into “Lunch on the Grass: Three Black Women”) so closely mimicked our three multitoned faces. “We have to take a picture!” Vanessa said. “Yeah. I know, right?!” responded Joni. Gloria agreed, “Fa sho!” Escaping briefly from our guided tour, the three of us decided to capture what would come to be an important moment for each of us. As Joni was about to capture the artwork with her phone, Vanessa stopped Joni and said, “No, we have to pose like the women in the work, in front of the work and get someone to take the picture of us.” So we did; each of us chose our positions on the floor, readying ourselves for the photo, glancing both at ourselves and backward at Mickalene’s three seated figures to be sure that our poses were in agreement (Figure 1).

That moment amplified not only our place within contemporary art history but also within our chosen profession. The nuances of our bodies, our figures, told an American story that largely remains ignored. During the moments of posing and trying to get our body positions and facial expressions just right, we knew and felt that we were doing something subversive and nourishing. We knew we were having an experience that was ours to own. When we returned back to the conference, there was a renewed sense of audacity to “just be.” We were emboldened, and reinvigorated by conversations ignited from that experience. Our Black and Brown Womanness was made more public in that instance.

***

The above narrative provides context for understanding how we, three art educators who are WoC, struggle to engage with a discipline that has historically paid little attention to the intersectionality of race and gender and its systemic impact on the field. For us, Thomas’s work visually captured the nuances of the racialized experiences among and between the three of us. More importantly, her work conceptually represented the ways in which the three of us work and maneuver within our predominantly White female field of art education. Just as Thomas’s intentions were to position her figures in relation to art history and the contemporary culture at large,[1] our intentions, whether or not we knew it at the time, were also a pointed commentary on the historical placement of WoC in art education. We would later make a commitment to return to our photograph, and Thomas’s work, in order to tease out the dimensions of these nuances. This article is the product of that commitment.

Figure 1. Vanessa, Joni, and Gloria seated in front of Mickalene Thomas’s “Le d,ejeuner sur l’herbe: Les trois femmes noires,” 2010.

According to data obtained from NAEA, the art education field, similar to the general education field, is over 80% White and female.[2] At its core, art education transcends preparing future preK–12 art teachers, it is also about recognizing the role the arts play in society. Such significant intention demands that critical connections be made between ones’ self and others, especially as it relates to representation. Unfortunately, the absence of Black and Brown voices in the art education field has resulted in hegemonic research, teaching practices, and ways of knowing and engaging in art that disregard our varied and divergent interpretations of the world. Black and Brown women’s knowledge, truths, and lived realities are often pushed to the periphery, or altogether silenced.[3] Likewise, WoC are often left out of the dominant paradigms, methodologies, research, and discourse of art education. WoC have had no “home place”[4] to attend to gender and race simultaneously in art education. In a field that is dominated by White women whose feminism more often disregards intersectionality, we, the authors, seek to consider what languages, actions, and considerations we deem necessary to shift the art education discourse so that it is attentive to the needs of WoC. Without considering the intersectional realities of WoC, the ways art educators articulate the role the arts play in society will be flawed.

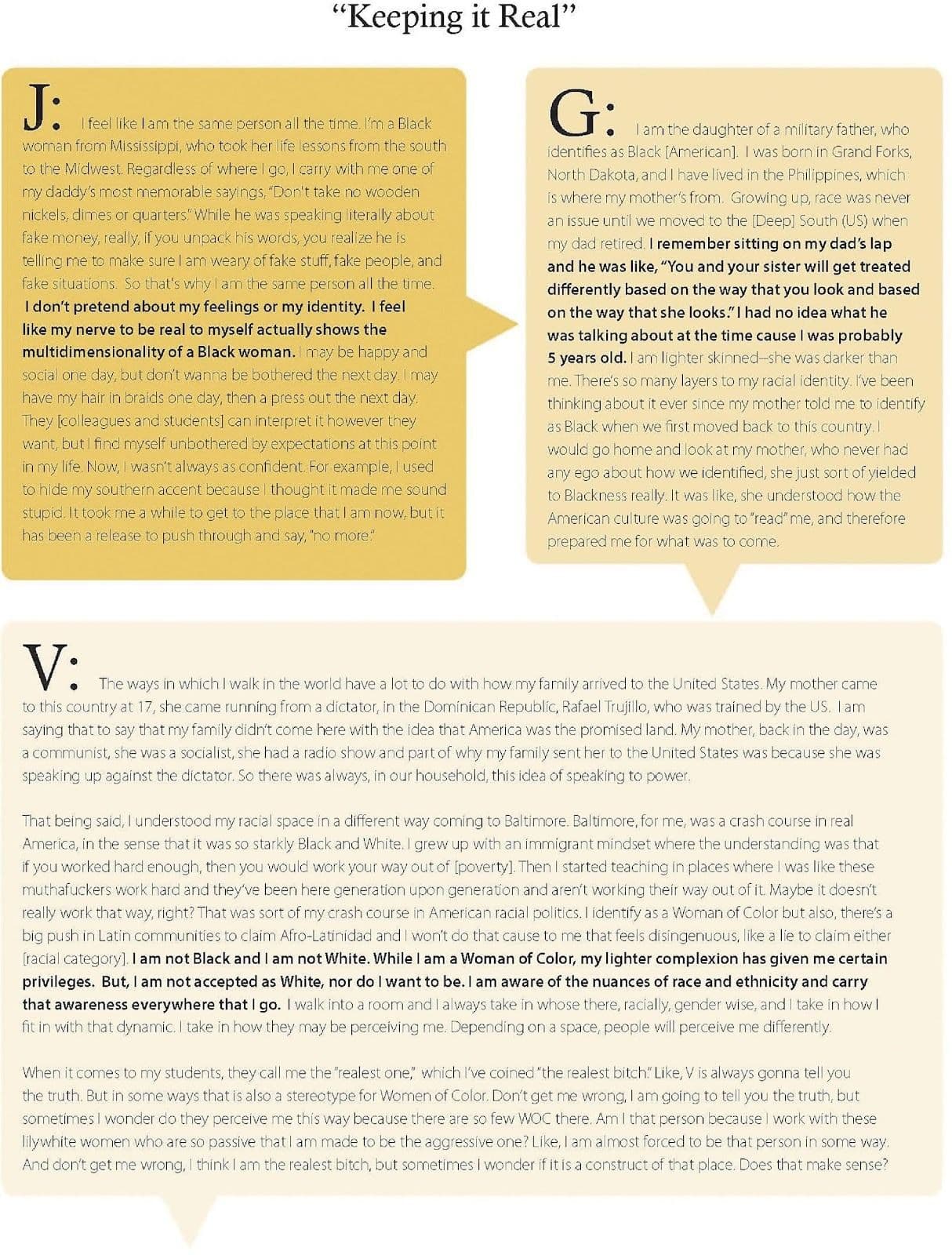

Figure 2. Vanessa, Joni, and Gloria on video chat discussing their identity alongside images of Thomas’s artwork.

This article, while academically driven, emerged from dialog that took place among and from a place of sisterhood and informal community building. This trioethnography, a collaborative ethnographic research methodology, began with our initial visit to the SAM and interactions with one another around Mickalene Thomas’s artwork. Following that experience, the three of us engaged in a two-hour-long conversation discussing our experiences as WoC working in predominantly White spaces and a predominately White female field (Figure 2). Our conversation began with the simple, yet beautifully complex question, “Who are you?” Ultimately, our dialog centered race and gender and the ways we are constantly pushed to de-racialize and de-gender our bodies in the world at large, as well as in our professional locations.

Upon reading the transcript of our dialog, we recognized the ways in which our conversation conceptually aligned with intersectional feminisms like Black feminist thought and Chicana feminism. Therefore, we looked to scholarship from feminists of color to tease through the complexity of our both gendered and racialized identities and to find ways to counter the negation of our voices and bodies, specifically in the field of art education.[5] Intersectional feminisms allow us to examine the “various ways in which race and gender interact to form the multiple dimensions of Black women’s experiences, especially in employment.”[6] Through this process, we have been empowered to recover and reclaim our subjugated voices, and respond to how matrices of oppression reinforce each other in varying contexts.[7] Additionally, intersectional theoretical lenses help us to self-define, and see the significance of self-valuation, self-reliance, independence, and respect, which can be used as strategies of resistance against both racism and sexism.[8] With these feminisms at the forefront, we are able to more precisely critique and identify the invisibility of WoC in the field of art education, and subsequently make a case for why a revisioning of the discourse is necessary.

Our collective voices provide multiple understandings of lived experiences and share characteristics of collaborative dialogic methodologies.[9] As a trioethnography,[10] we speak each other into being, and see each other into light. By using trioethnography as a methodology, our voices and shared experiences become the site of inquiry—a narrative of resistance in relation to dominant narratives/discourse. We create an interactive third space[11] and encourage the readers of our dialog to examine their own experiences and question dominant narratives.[12] To these ends, no singular experience holds universal truth, but collectively, we express a multiplicity of embodied truths. In fact, these differences are encouraged in collaborative ethnography.[13]

As WoC, our distinct dialog merges in ways that reveal joy and pain; it is not for the faint of heart. As Norris, Sawyer, and Lund note, “[Trioethnographies] are fluid texts where readers witness researchers in the act of narrative exposure.”[14] We expose our vulnerability through raw and authentic language. We invite the reader into this dialog as a means to engage with our lived and shared truths. What emerges from our original conversations with one another are connections to our past, which in effect inform our present and future experiences. We build on Pinar’s[15] concept of currere in that, just like a curriculum, our lives carry acquired/learned knowledge and belief systems. We also believe that, through this dialogic process, we have developed a deeper understanding of self in relation to another. Thus, our trioethnography extends currere by interrogating our personal stories while “inviting the Other to assist in the act of mutual[ly] reclaiming” these stories.[16] Ultimately, we found resonance in this methodology, in order to honor each of our individual voices, while co-constructing a broader narrative of intersectionality. By juxtaposing our voices, we give space for sharing a multiplicity of truths, yet making our collective experiences as WoC of central importance.

The following sections of this article are organized into the three major themes identified as we analyzed our trioethnography. The three themes are “Keeping it Real,” “Invisible Burdens,” and “Kinship Ties.” Each section opens with excerpts of our transcribed conversation, followed by an analysis of that dialog using intersectional feminist scholars. We then connect our analysis back to Thomas’s work—the inspiration for this trioethnography. The concluding section of this article offers implications and correctives for the field of art education.

The following dialog begins at our beginning. Who are you? Where are your people from? How have you arrived here? Without assumptions, we asked and listened. By starting in this way, the dialog creates space for us—Joni, Gloria, and Vanessa—to engage in authentic discourse, grounded in each of our lived and embodied experiences. Eventually, the recurring theme emerges and is centered around the ways in which our embodied realities are often viewed as caricatures and stereotypes by our university colleagues and students.

Jackson writes, “Classifications by race, class, gender, sexuality, ethnicity, and nationality are all shortcuts—templates used in lieu of absolute interpersonal transparency.”[17] If we do not dig deeper and look beyond the obvious, we remain stuck in our own and society’s definitions. The entire dialog shared above demonstrated an exercise in interpersonal transparency. Joni opens the conversation about personal identity by referencing her daddy’s advice: “Don’t take no wooden nickels, dimes or quarters.” From the beginning she articulates her sense of self from a place of authenticity and sincerity, finding comfort in her southern roots, yet there exists a tension. She addresses the “nerve to be real” while admitting to previously disguising her southern accent. Joni’s internal conflict can be analyzed through the lens of W.E.B. Du Bois’s double consciousness. Double consciousness is described as follows:

It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One ever feels his two-ness,—an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.[18]

As a result of being a Black woman, Joni is forced to see herself not only through the lens of Blackness and Whiteness, but also through the lens of patriarchy. While Joni continues to push against the expectations and limitations of her colleagues by embracing the “multidimensionality of Black womaness” as evident in her comments about her moods and her hair, she also recognizes the moments when Black people, especially Black women, feel the need to assimilate. Meaning, Joni’s previous decision (conscious or unconscious) to hide her southern accent was made as a means of survival; specifically, for her professional advancement within predominantly White female spaces.

As Jackson asserts, the need to “keep it real” is directly tied to society’s preoccupation with its own limitations and contours.[19] We all, as humans, construct our identities with these imposed societal limitations. These societal limitations often require many WoC to be disingenuous and they tend to normalize one’s inauthenticity. This forces many WoC to participate in their own erasure in the workplace, and in society at large.[20] This is evident in Gloria’s mother’s insistence that her children identify primarily as Black based on society’s narrow understanding of the nuances of race. To her mother, Gloria’s phenotype “reads” Black, her lived experiences are based on that perceived Blackness, thus, simply, she is Black. While we know that race is not as fixed as this, Gloria’s mother’s yielding to Blackness, rather than asserting a biracial Black and Filipino identity, acknowledges that she recognizes society’s lack of concern or interest to embrace the fluid and diverse racial identities of people of color. Gloria’s mother actively participates in the erasure that Crum mentions by flattening Gloria’s biracial identity. Instead, Gloria’s mother seems to be leaning on the strength of the collective identity. Collective identity, being part of a group, is both freeing and limiting. Collective identities often provide a framework or narrative in which to situate our stories, yet they can lead to essentialist perceptions, especially when we consider who gets to define Blackness.[21]

Vanessa’s comments about being neither Black or White [enough] highlight the tension with racial designations as well. Being a first-generation immigrant WoC with a lighter complexion, Vanessa is keenly aware of both her oppression and her privilege, as made evident in her comment “while I am a Woman of Color, my lighter complexion has given me certain privileges.” Hailing from a country where the overwhelming majority of its inhabitants are of darker complexions, within the Dominican Republic, Vanessa’s lighter complexion is a rarity and comes with privileges. Analyzed through the framework of colorism, defined as “the allocation of privilege and disadvantage according to the lightness or darkness of one’s skin,” within Dominican culture, Vanessa’s “lightness is associated with White Europeans and is therefore preferred and viewed as superior to darkness, which is associated with indigenous and Black African people.”[22] Yet, as Vanessa noted during her reference to racial categorizations in Baltimore, Maryland, context matters. In the United States, as a Latina of Dominican descent, Vanessa is what folks would describe as “racially ambiguous.” In the U.S. racial binary paradigm, Vanessa’s phenotype reads as “other than White, but not Black.” So while Vanessa has light skin privilege in some instances, she also is, at times, simultaneously marginalized, as she is often alienated from both Latin and Black culture in the United States. As Quiros and Dawson argue, “the social construction of whiteness as a privilege may not be internalized as a privilege for Latino/as who choose to identify with their ethnicity rather than with their perceived race. This brings into question how the way one chooses to identify may conflict with how one is identified by others and also warrants further exploration into the perceived privilege associated with Whiteness.”[23]

For Vanessa there is a struggle in finding a true home in either racial world. Identifying with more than one racial, ethnic, or cultural group causes higher levels of dissonance and in turn complexity.[24] This is evident in Vanessa’s comments about how she perceives herself, how others perceive her, and how she chooses to situate herself among the differing perceptions. The lack of understanding of the role colorism plays within Latinx communities and the ways in which that differs from White American and Black American communities is essential to understanding the racial experiences of Latinos/as/x in the United States.[25]

In the concluding section of this particular conversation, both Joni and Vanessa share experiences of being stereotyped by colleagues and students. Vanessa details how she is perceived as “the realest one” and feels like she must always speak to “truth” in comparison to her White colleagues. Joni shares an exchange with a White female ally, as she sought advice about how to navigate the tension in negotiating the “angry Black woman” stereotype. Joni remarks, “I was calling shit out left and right. And I’m like, you know, it’s a fine line between being the person who calls shit out all the time and it being appreciated, and being labeled as ‘a complainer’ or ‘a bully.’” Joni’s statement reveals that she recognizes how certain preferred behaviors are associated with Whiteness, while, in contrast, problematic behaviors are associated with different communities of color.[26] She further articulated the desire and need for others in her field to speak up against injustices, specifically White allies.

Both Vanessa and Joni comment on being perceived as aggressive by their colleagues. Vanessa comments, “Am I that person because I work with these lilywhite women who are so passive that I am made to be the aggressive one?” Scholarship on Black women faculty and students’ perceptions confirms that “black women faculty are trapped in negative race and gender stereotypes where they are considered as both aggressive and less competent by their (often white) male colleagues and students when being assertive.”[27] The stereotype becomes a trap in which assumptions and expectations leave no room in which responses and behaviors can be viewed authentically. In Black Women’s Dilemma: Be Real or Be Ignored, Cook writes, “Black women respondents overwhelmingly reported feeling different and unappreciated. They’re frustrated and tired of defending themselves against being labeled as angry, loud, aggressive, rude and obnoxious.”[28] Joni’s comments testify to this when she says, “that label does become like a caricature, and then an expectation based on that stereotype, and when I don’t step up and call shit out, it’s like oh what’s wrong with you today Joni? You depressed? You sad? No. I can just not be that person who needs to call out ‘all the shit.’” Anger, frustration, and resentment are often a consequence of the lack of acknowledgment of external challenges WoC face. In the 2018 text entitled Eloquent Rage, Black feminist scholar Brittney Cooper suggests that instead of identifying Black women’s anger as an emotion that should be tempered and suppressed, we should share this authentic emotion because anger keeps us honest.[29] This is evident in Joni’s remark, “I can’t let people get away with racist bullshit because if you let them get away with shit, they will think it is ok.” Joni feels like she has to be assertive and passionate about injustices that happen around her, especially those that impact her as a Black woman. Yet what we find is that by honoring her values and beliefs, Joni’s actions are often perceived as anger. Walkington agrees: “When black women’s assertions are aimed toward their own benefit, negative stereotypes come forward, more powerful colleagues and administrators label these women as aggressive, and black women’s progress in academe is stunted.”[30] These consistent and “constant cultural assaults on their identity [stemming] from historical stereotypes” make it so WoC feel they cannot be their true selves at work.[31] “The angry Black woman” and “the sassy-spicy Latina” are external definitions and stereotypes, what Collins calls “controlling images.”[32] These images, when not questioned, act as a form of domination utilized by those in power, here White women, to make sexism and racism appear as normal and inevitable parts of life.[33]

In the above passage, Vanessa refers to cloaking herself in the stereotype both as an act of defiance and resistance and as a performance. She states, “Oh, you want me to be that person? Ok, I am going to be that person for you. But some of my colleagues don’t even get it. … They don’t get that sometimes it is a performance on their behalf. Unfortunately, this performance sometimes impacts their lack of understanding of my multidimensionality.” As Tesfagiorgis writes, “without a discourse of their own, Black women artists remain fixed in the trajectory of displacement, hardly moving beyond the defensive posture of merely responding to their objectification and misrepresentation by others.”[34] Both Vanessa and Joni wrestle with external definitions and stereotypes. We see this when Joni says, “In addition to me being in this Black woman body, the role of being ‘the realest bitch’ brings up a whole heap of stereotypical bullshit that I then have to work to detach myself from [when I want to be something else].” Henderson, Hunter, and Hildreth claim that Black women faculty enact Black Feminist Thought by declaring their self-valuation and self-definitions as able and competent scholars, which in turn highlights the intersectional nature of race, gender, and class oppression, and solidifies Black female culture as a strategy of resistance.[35] Both Joni and Vanessa share experiences in which their behavior, and thus their reality. are outside of colleagues’ expectations. The dialog throughout this section illustrates our desire to have “the power to name one’s own reality” outside of the dominate narrative.[36]

The dialog in this section sheds light on the invisible burdens that WoC faculty endure in academic spaces. From the complete disregard for their intersectional identities, to colleagues’ and students’ racially problematic behaviors and attitudes, we, the authors, engage in an intimate conversation that highlights widespread marginalization and discrimination in our institutions and professional relationships.

Vanessa’s opening comments in this section give much needed attention to the way intersectionality impacts family–work life balance for WoC in academia. In addition to her speaking about motherhood as a woman faculty member, Vanessa acknowledges the ways her immigrant identity informs her personal and professional priorities. Primarily, family obligations, such as caring for children, often fall on faculty women.[37] A 2017 study conducted by the Social Sciences Feminist Network Research Interest Group (SSFNRIG) confirms, “Much like the invisible work in the academy, women are also responsible for more of the invisible work at home. On average, because women have more responsibilities at home than men, women actually work more hours than men.”[38] However, Vanessa’s experience as an “immigrant woman of color” adds an additional layer of personal expectations and challenges to her position as faculty. The obligation to assist and support the family is a critical priority in immigrant families.[39] Specifically, “young adults from Filipino and Latin American families reported the strongest sense of familial duty during young adulthood.”[40] This is evident in Vanessa’s insistence to drive from Baltimore, Maryland to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania to care for her daughter for a few hours, and then drive back to Baltimore to teach a class, all in one day. Furthermore, Vanessa talks about her ability to “handle [her] business” without colleagues questioning her commitment to her responsibilities as faculty. The taxation evident in Vanessa’s comments is consistent with research that explains that women, specifically WoC, in academia work overtime out of fear of being perceived as incapable or incompetent by their White male counterparts.[41] SSFNRIG writes, “Historically, universities have been maledominated, with clear images of the ‘professor’ as a learned man with no obligations aside from his scholarly university tasks.”[42] Meanwhile, Black women and other female faculty of color disproportionately juggle family work and even community responsibilities.[43]

Vanessa’s dual identity as a woman and immigrant of color place an additional set of implicit emotional and mental expectations on her that are rarely considered by individuals unbounded by racism and sexism. Even more, most institutional sites disregard the ways intersectionality impacts how female faculty of color progress toward professional milestones like tenure and promotion. Acknowledging intersectionality in academia is critical, as it disrupts the myth that the playing field is even and that everyone should succeed because they are afforded the same opportunities. The truth is, for female faculty of color, the starting line can be miles behind their White male (and even female) counterparts.

As the conversation progresses, readers see Joni’s desire to push back on the ways the invisible burdens of people of color maintain their invisibility. Recalling a request to “take over” her department’s Instagram page for a day, Joni admits that she was uncomfortable sharing snapshots of her day on social media because she believed the simplistic images would not adequately capture the dynamic intersections of her world as a WoC in academia. While the request from her department seemed innocent and simple, Joni asserted that these “snapshots” would actually highlight the invisibleness of her struggles, thus invalidating the significant challenges that she experiences daily. Joseph and Hirshfield write, “Faculty of color, especially female faculty of color, often have to navigate ‘personal and psychological minefields’ because they must balance stressful academic and personal lives … ”[44] As a result, female faculty of color may eventually come to experience racial battle fatigue (RBF), which refers to exhaustion-associated environmental stress associated with race and racism.[45] RBF can also result in “emotional and social withdrawal.”[46] Aspects of Joni’s narrative align with symptoms of RBF, specifically her description of the ways certain racially motivated events in the world were “on” her and “attached” to her, mentally and emotionally. In a narrative essay about experiences with RBF in academia, Acuff writes,

There is emotional and psychological baggage that Black people accumulate after being required to perform, function, and thrive in a world that was created with the goal for Black people to fail on multiple levels. Historically, Black people in the United States have been required to live within the constraints of a specific narrative that they did not have the chance to create or modify. Regardless, Black people have to work within that imposed narrative, or they work to the point of exhaustion to counter that narrative.[47]

Joni’s decision to decline the request to “take over” her department’s Instagram can be identified as an explicit rejection of the “performance” Acuff discusses here. Furthermore, constructing and disseminating simplistic narratives that disregard the complexity of the lives of WoC is problematic and is heavily critiqued by Black feminist scholars.[48] It is imperative that WoC come to their own voice, selfdefine, and begin to more aggressively assert ownership over their narrative and the imagery that represents them.[49] For Joni, this meant acknowledging the complexity of her racial and gendered identity and refusing to simplify it, even briefly, for the entertainment of others on social media.

Collins writes,

Being treated as “mules uh de world” lies at the heart of Black women’s oppression. Thus one core theme in U.S. Black feminist thought consists of analyzing Black women’s work, especially Black women’s labor market victimization as “mules.” As dehumanized objects, mules are living machines and can be easily treated as part of the scenery. Fully human women are less easily exploited.[50]

Walkington adds, “Black women’s labor as faculty is both the cheapest and least valued … ”[51] Collins’s and Walkington’s claims are illustrated in the above dialog as Gloria begins to detail her overwhelming university workload. Gloria explains that while her efforts surpasses her institution’s expectations for an untenured faculty, she steadily feels pressure to do more. Gloria shares the ways in which a senior colleague [White, female] attempts to micromanage and question her methods and ability to develop art education curriculum. SSFNRIG reports,

Faculty of color report incidents of colleagues questioning their merit, a lack of comradery in predominantly white institutions, and a delegitimation of certain research interests and methods (Joseph & Hirshfield 2011; Padilla 1994). These persistent slights create a “double doubt” (Griffin et al. 2011) where faculty of color feel both an internalization of not being good enough and external pressures to do more and be twice as good as white colleagues.[52]

Also, in addition to the more explicit pressure, faculty of color often work under the assumption that White colleagues see them as underqualified or that they were hired under affirmative action. Therefore, they believe that they must work twice as hard to receive equal respect as White colleagues.[53] This level of overcompensation can be identified as a symptom of negative stereotype threat, which refers to a person’s fear that they are being treated or judged based on a racial stereotype.[54] Recognizing that a negative racial stereotype may be attached to how you are perceived can result in intentional actions that aim to dispel the stereotype. However, unfortunately, sometimes these actions may be counterproductive to a person’s well-being. SSFNRIG writes, “Faculty of color [experience] more stress and anxiety, and a loss of sleep as a result of this unequal burden … ”[55] Gloria’s final comments in this section align with SSFNRIG’s claims. Specifically, when Gloria implicates herself in the exploitation of her labor and states that the burden is sometimes “self-imposed,” this implies that there is some kind of internal anxiety that is driving such self-inflicted pain. Vanessa validates this personal, anxiety-driven overcompensation by responding to Gloria, “It’s almost like because we are not doing it the way they [White women] are doing it, we are going to do the absolute most to show you that we can do it.”

While Vanessa’s comment confirms Gloria’s assertion about the self-imposed burden, her statement also reveals a unique tension within some aspects of intersectional feminist work. Vanessa’s declaration of self-valuation and self-definition communicates both power and inequity simultaneously. In her text, Borderlands, Chicana feminist Gloria Anzaldua[56] calls out the historical practice of people of color needing to model after or align themselves with Whites in order to receive similar privileges and rights. Anzaldua maintains that the power of self-definition is critical for people of color. This is also a key assertion emphasized by Black feminist thought (BFT).[57] Patterson, Kinloch, Burkhard, Randall, and Howard agree: “We resist by disallowing dominant, mainstream interpretations of who we are to overshadow, minimize, or discredit our truths. This act of self-definition, a core theme of BFT, is in itself an act of resistance.”[58] Vanessa asserts that she is purposeful in not modeling herself after White women, which implies that she has a positive self-belief system. However, she admits that we [WoC] have to “do the absolute most” to prove that our way of doing things is just as effective. This tension illustrates the unequal burden that female faculty of color endure in order to release themselves from oppressive systems of power, even when using emancipatory frameworks that seek to empower those in marginalized groups.

The conversation in this section concludes with Gloria discussing microaggressions that she experiences during daily interactions with students. Microaggressions are “acts of disregard that stem from unconscious attitudes of white superiority and constitute a verification of black inferiority” that are pervasive and at times innocuous, but their impacts are substantial to people of color.[59] People of color are left feeling inferior and even silenced by microaggressions. SSFNRIG writes, “These ‘gnat-like’ problems are not necessarily extreme enough to warrant harassment suits, but they include micro-level interactions such as not inviting women to social gatherings, making sexist jokes, or students and colleagues referring to women as ‘Ms.’ rather than their professional titles … ”[60] Gloria talks about the way students call her White female colleagues “doctor” in the academic setting but do not address her with the same respect. The consistent devaluing of Gloria’s degree and status as “Dr. Wilson” is not only a microaggression, it is a microinvalidation that communicates that she is perceived as less than when compared to her White colleagues, if not simply an inapt educator, researcher, and scholar.[61]

The conversation that opens this section demonstrates the increased and amplified weight that accompanies being a double minority in academia. Joseph and Hirshfield write, “Issues of racism and diversity affect faculty of color more directly than their white peers, addressing such issues with colleagues is a burden that many respondents of color feel they must bear.”[62] Anzaldua describes Mexican immigrants as being faceless, nameless, and invisible as they make their journey to cross the borders into America.[63] She characterizes them as fearful, yet filled with courage. As evident in the dialog shared, WoC in academia can identify with this characterization, as they must continually attempt to cross the heavily patrolled borders of academia—borders that were never meant to be crossed by people of color in the first place.

This final section of the article focuses on relationships, specifically the development of “kinship,” which is also a running theme in Thomas’s artwork. The following dialog begins with Vanessa’s description of the picture-taking experience at the Seattle Art Museum.

The final section of our dialog captures the catalyst and inspiration for this article—our visit to a museum exhibition, featuring the artwork of Mickalene Thomas. As the only female artist among three other artists in the main exhibition, Thomas’s complete body of work resonated with us in a powerful way. As we were guided through the exhibit, we were particularly struck by her 2010 painting titled Le d,ejeuner sur l’herbe: Les trois femmes noires. Invited to lounge in front of the painting (there were chairs deliberately installed as part of the work), each of us seemed to connect to the women represented in the work. As Vanessa recounts the experience, Joni adds her thoughts about the White male intruder. Joni states, “You are disrupting this special kind of moment that allows us to think about ourselves in this space and putting your damn White male gaze on it.” Vanessa and Gloria agree with Joni without hesitation. Joni, Vanessa, and Gloria’s feeling of objectification references the historic ways the Black female body has been viewed and captured through the photographic lens of a White gaze.[64] Gloria’s remark about “the idea of the spectacle and cooptation of bodies and cultures,” lends a nod to scholarship around Sarah Baartman (Hottentot Venus). Baartman was a Black South African woman whose body was the site of disparaging presentation and broad White European ridicule and reduced to a sexualized nature.[65] Vanessa’s verbal rejection of the White male viewer’s request to take the group’s picture acted as protection of a shared personal moment and connection to the Thomas image. Vanessa’s assertion informed the White male viewer on “how not to treat black bodies.”[66] It also served as a form of solidarity and resistance to the White male gaze. Additionally, by intentionally selecting to have another WoC to take our photo, we enacted a deeper unspoken solidarity. We found strength in sharing the experience of taking a picture with Thomas’s work, and we also found strength in sharing the moment of discomfort during the disruption.

To these ends, this section of our dialog also reveals the salience of what scholars have referred to as “fictive kinship” ties.[67] Fictive kinship can be understood as having a deep and personal relationship with unrelated individuals, such as close friends, and acknowledging and bringing these individuals into an extended family network. Often these individuals come together from shared lived experiences of historic oppression (especially among Black Americans) and often address one another using familial terms such as “sistah or brotha.”[68] The collective, communal, and kinship cultural roots of these systems of support are found within the fabric of the African culture[69] and are arguably inherent in the worldview of Black women.[70] These and other kinship ties have proven integral in how we (the authors) have each managed to cope and sustain our professional identities, as well as navigate the challenging notions of being an intellectual within a White female–dominated field.

Our encounter with Thomas’s work in the museum allowed us to capture a moment that each of us found empowering and nourishing. We connected with one another as “sisters” through our shared experience in the museum and our shared understanding of oppressive structures in higher education. Our fictive kinship filled in the gaps of mentorship networks that are often left out of institutionalized goals of the academe. This connection of sisterhood is stressed in Black feminist thought.[71] With a combined 17 years of teaching within higher education spaces, we have each experienced challenges associated with navigating our professional racialized identities. In this case, our connection to the museum experience offered us at least two things: (1) reprieve from a “professional” space, where we are often called to perform within uncomfortable circumstances and (2) reconnection with our more authentic selves through personal encounters with one another and with the art world. The latter holds particular importance, as it has been noted how powerfully these bonds of connectedness help to reinforce positive identity narratives.[72]

The representation of identity narratives of people of color (and other historically marginalized groups) has been the concern of visual arts and cultural studies scholars for decades.[73] Wilson suggests that visual imagery holds particular importance as a potential space of kinship.[74] Historic deficit and/or derogatory visual narratives are often produced by White creatives (e.g., filmmakers, advertisers, fine artists), so when Black Americans are able to see themselves represented positively in visual culture, it fosters a sense of agency. Our multilayered connection to one another, as friends, and also to Thomas’s imagery, offered the support and renewal that we needed that day.

Joni’s statement, “I wish I would’ve had this a lot earlier,” makes reference to larger systemic issues of support deficits, like peer mentorship, that WoC in higher education are faced with. Scholarship on the necessity of coping mechanisms among Black women professionals[75] supports Joni’s realization that these opportunities were lacking for her. She shares that while she has been in the academe for seven years and has elder mentors, it has been challenging for her to find a Black female peer with whom she can connect professionally and socially. While mentorship relationships are crucial,[76] limited access to important peer-to-peer relationships is yet another barrier Black women face in higher education. In our shared dialog, each of us indicated the need for and reliance on strategic survival techniques and the importance of the social support of kin-like peer networks.

As revealed in our discussion, our peer network was solidified during the NAEA conference and the museum visit. Walkington writes, “Peer mentoring relationships appear fundamental for black women faculty’s resistance against internalizing their marginalization as they also provide feedback, share information, and give advice on work related issues … ”[77] For example, doing the work for this article allowed us to psychologically and physically resist isolation and support one another against a climate that is less supportive.[78] Our extended kinship network[79] served as an additional buffer against psychological isolation[80] and the stressors associated with navigating the dominant White community of art education. This supports Daly, Jennings, Beckett, and Leashore’s work on the importance and necessity of communal support networks among Black Americans.[81] As Gloria mentions, our community as three WoC not only serves as professional support but also as an act of self-care and effective coping strategy.[82]

Faculty of color frequently sit behind closed doors among each other and call out problematic behavior, erasure, marginalization, and the silencing by White colleagues and peers in their field. In academia, our uncensored narratives that detail these experiences are rarely shared in academic venues, especially fieldspecific journals. WoC’s ways of resisting have even become mediated by the dominant group, as we are often inclined to double check our tone and be hyper aware of White fragility.[83] However, this trioethnography resists that mediation. What we shared in this article is personal, and left in its raw, emotional state. It is highly inconsiderate of White fragility but critically considerate of the authentic, unfiltered experiences of WoC. Further, as academic writers, we struggled with sharing our unedited, sometimes profane, dialog. We contemplated about how it might be perceived/read by a reviewer for an academic journal. However, during this discussion of language and voice, we realized that, once again, we were editing and mediating our “selves.” Therefore, ultimately, we opted to leave our dialog in its original state, the way it left our mouths. We believe that this type of intimacy, passion, and unfiltered rawness is a form of resistance. Further, to bring the conversation full circle to the place this trioethnography began, we identify similar patterns of connection and resistance in Thomas’s artwork, Le d,ejeuner sur l’herbe: Les trois femmes noires.

Visiting the museum that day, we were easily drawn to the image of the three Black women in Thomas’s work. No mention of losing track of our tour group; no prior conversation about why we wanted, rather, needed to take the photo; we all simply moved confidently into place, paying deliberate and careful attention to stylize ourselves in the same manner as the women in the painting. We felt kinship to these painted women and also to one another in that moment. Similarly, using friends and family in portraits, Thomas’s sitters have relationships with her and among each other, which helps build a strong foundation for her work.[84] Thomas notes that she cannot successfully create without them—she sees them as a support system and leans on their shoulders. In a sense, by positioning our bodies directly in front of the artwork, as a reenactment of Thomas’s painting, we served as an extension of this kinship; a third space of connectedness—to one another, to the painting, and to Thomas herself. These relationships, in some ways, are subversive acts. For example, Patterson et al. write, “[Patricia Hill] Collins explains that ‘self’ is not defined as the increased autonomy gained by separation from others. Instead, the connectedness among individuals results in deeper, more meaningful forms of self-definition, empowerment, and solidarity. By establishing group solidarity, collective resistance against oppressive forces can be bolstered.”[85] Thomas’s artwork is more powerful because of her support system,[86] as is this trioethnography.

Similar to the way we claim our agency in this article, Thomas asserts the Black women sitters’ agency by centering their Black Womanness front and center. Thomas states, “Painting Black women is a revolutionary act.”[87] WoC should continue to create images of themselves as a form of resistance.[88] Thomas’s figures are dressed in bold colors and they pierce directly at the viewer, “sizing us up.” She states,

I’m so interested in this idea of being seen and seeing yourself, and how that relationship is developed. We all want to be validated and recognized in some way. This also relates to the power of the gaze in my work. When I take a photograph, that gaze is forcing the viewer to see my subjects—to recognize them.[89]

Thomas pushes back on the White male gaze that is so familiar in art history, and counters the objectification of the female body by constructing a Black female gaze. Likewise, we too are bold in our stance, in our statements, and our language in this article. We want to be seen and heard, but we reject “the gaze.” The Black women sitters’ confidence makes it difficult for viewers to impose a false narrative upon them. As WoC in academia, we are rarely seen as intellectuals, people of character, or productive colleagues in the academe[90]—this narrative is our burden. So, much like Thomas inserts Black women and their truths into the art historical canon,[91] we aim to do the same with this article.

The narratives shared under the thematic headings of “Keeping it Real,” “Invisible Burdens,” and “Kinship Ties” are but a few lived experiences shared by WoC in academia. While the dialog that emerged from this trioethnography was not always specific to art education, our words, lived experiences, and concerns at large should be considered in the feminist discourse of art education and in art education research. In other words, we as art educators cannot distance ourselves from being WoC who are impacted by the intersections of our identities and our professional workplace and world. To deny these intersections would be to ignore our locations within the art world and education. The problematics of feminism in art education mimic the historical yet ongoing social critique of the mainstream feminist movement—it centers White women.[92] In 1984, Audre Lorde asserted, and it still rings true today, that “the failure of academic feminists to recognize difference as a crucial strength is a failure to reach beyond the first patriarchal lesson. In our world, divide and conquer must become define and empower.”[93] So, to the art education field, we put forth the following correctives (aka, the languages, actions, and considerations), which purposefully align with the themes found in our trioethnography: Let’s all keep it real. Let’s make the invisible visible. Let’s hold each other down.

Every kind of Black woman has fought for our right to be free to travel in pursuit of dreams and destiny. One way to start shedding the baggage is to start telling our truths, to start opening the bags and exposing the lies that weigh us down. The weight of the nation is not ours to carry.[94]

Historically, White people have controlled the narrative about the ways people of color should perform in the world. We have found that White people’s perceptions of “keeping it real” in academia limits our ability to express the fullness of who we are. This perception often brands us as assertive, immovable, “angry,” and “strong.” Although, at times, “keeping it real” or truth telling is a means of unloading frustrations, it also has the potential to become a trap of sorts. WoC in academia are often pushed into these essentialized characterizations that unfortunately do not allow us to be vulnerable, caring, or joyous. Our understanding of “keeping it real” as WoC includes all of these ways of being; assertive, immovable, sometimes angry, strong, and simultaneously vulnerable, caring, and joyous. The corrective is to accept the multitude of ways WoC show up, act, and speak. Honor the ways in which we “keep it real” given the situation, time of day, who we are speaking to, and so on. It is time for us to control our own narrative of what “real” is and can be.

Further, our White counterparts need to start keeping it real. White art educators, especially in academia, must examine, probe, and question their own positionality. They must reflect on the ways they have embodied Whiteness and how this influences their art education research and pedagogy. McManimon and Casey write, “race [is] historically and socially variable, situated in and entangled with other identities and context,” yet whiteness functions normatively.[95] By not examining their lived experience through a racial lens, White people cosign on the White experience as normative. Not examining Whiteness and its languages, actions, and considerations removes accountability for microaggressions and the impact of intention and ultimately positions everything other than White as outsider. The corrective is for White academics to engage in continual antiracist professional development coupled with a practice of consistent self-reflection and analysis. As McManimon and Casey write,

As white educators, we are always in the process of becoming antiracist pedagogues; the moment we think we have “arrived” is the moment at which we have stopped learning and thus stopped our most important teaching. “(Re)beginning” both honors the experience gained in processes of action and reflection in PD and classroom spaces and recognizes the need for humility and continuous learning in any anti-oppressive pedagogy.[96]

Racism functions in institutions and systems as well as in minds and hearts. For White academics, the practice of “keeping it real” is one of constant (re)beginning and becoming.

Much of the psychic pain that black people experience daily in a white supremacist context is caused by dehumanizing oppressive forces, forces that render us invisible and deny us recognition.[97]

One of our “invisible burdens” as WoC in art education is the ongoing effort we must make to become more visible. As a corrective, all art educators, specifically our White counterparts, need to actively confront the gross omission of WoC in art education writ large. To begin, there needs to be a deliberate, public, and consistent acknowledgment of WoC’s intellectual and artistic production. This means art educators need to seek, find, and read our research and journal articles and attend our conference presentations and art exhibitions. Additionally, as a followup to this kind of intentional action, it is imperative to cite WoC’s work in art education research and journal articles, assign our articles in your classrooms, and name WoC art educators as leaders in the field. While our knowledge is valid regardless of these actions, centering WoC’s voices in research, published manuscripts, and in classrooms historicizes and institutionalizes our knowledge. It is imperative to critically reflect on and change myopic citation practices, as scholars’ citation practices feed into who makes the canon, whose voices lead the discourse in research and teaching, and whose knowledge comes to be most valued by early career scholars and teachers.

Also, the blatant omission of WoC in research implicates art education in WoC’s continued oppression.[98] Therefore, all art educators need to recognize and consider the lived experience of WoC when doing art education research, as these considerations ultimately impact framing questions, theoretical and conceptual frameworks, methodologies, study sites, and research conclusions and implications. Research that disregards the intersectional experiences of WoC ends up inappropriately generalizing research findings across groups and even offering recommendations for moving forward in art education that may not be relevant or even possible for WoC.[99] Ignoring the explicit ways WoC engage with the world through simultaneously racialized and gendered lenses is problematic and overwhelmingly dismissive. The result is the dissemination of research that has limited implications for WoC or we are forced to make meaningful connections for ourselves.

Further, as it relates to visibility, intersectionality has never been at the core of how feminism has been explored in the art education field. Feminism and feminist theory have been weaved into art education discourse, research, and practice for decades. However, similar to the lack of intersectional considerations witnessed during the Women’s Liberation Movement in the 1960s, “feminist” art education has consistently failed to attend to issues that impact WoC. Overall, there is a lack of situational embrace for WoC in art education, especially at the institutional level. The system is structured such that WoC must choose between either racial oppression or gender oppression as a social justice issue. There needs to be acknowledgment and consideration regarding the ways systems of power interact in the lives of Black women and WoC that “restrict social mobility” and “hinder us from moving unencumbered through the social sphere.”[100] This enhanced recognition and visibility will surely shift the linear way feminist theory, as an epistemological framework, has been applied to art education research, practice, and the field. This shift would in turn affect how WoC preservice teachers, practicing teachers, and junior scholars see themselves, their voices, and their issues and concerns as respected contributions to the art education field. It is our hope and belief that if the visibility of and connectedness to WoC increases, so might interest in art education as a career, which would add more racial diversity to its overwhelmingly White demographic.

Caring for Black women’s actual lives means sitting with the acuteness of our fragility.

We break, too.[101]

To “hold someone down” references a colloquial phrase often used in Black American culture. It can be translated as meaning: to protect someone or otherwise support them. Dr. Bettina Love articulated a clear example of this as she described an event from June 2015 that involved 30-year-old social justice activist, educator, and Black woman, Bree Newsome.[102] Love detailed how Newsome scaled a flag pole to take down the Confederate flag at the South Carolina statehouse as a response to a then recent act of violence and hatred by Dylann Roof, a self-proclaimed White supremacist who murdered nine African Americans during a prayer service at the Emanuel African American Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina. A salient factor in Ms. Newsome’s ability to successfully scale and descend the flagpole to remove what is known to be a symbol of segregation and oppression, without harm from authorities, was the assistance from a coconspirator[103] and fellow activist, James Tyson, a 30-year-old White male. Nearby, a Charleston police officer stood ready to tase the pole—an act with potential for Newsome to fall violently from the top of the flagpole. Tyson swiftly responded by positioning his White body at the foot of the pole and subsequently gripping his hands firmly around it. Tyson knew that the police officer would not tase the pole as he gripped it, using his White body as a physical shield and protecting the vulnerability of Newsome’s Black body. More importantly, his presence was subordinate to Ms. Newsome’s, as he stood unobtrusively and quietly. Tyson could be considered a symbol of White male supremacy acting as coconspirator in a public display toward dismantling symbols of oppression; in other words, he strategically “held her down.” However, strategic acts of coconspiratorship with and for WoC are less commonplace within the field of art education.

We (the authors) have witnessed and have shared space with many of our White colleagues who have postured as allies, yet have failed to “hold it down” and strategize as coconspirators for and with WoC art educators. While these White art educators are able to regurgitate scholarship about oppression and marginalization, are quick to write articles about equity and diversity initiatives, and post pronouncements on social media platforms, fewer efforts are made to transform the field at institutional (policy) levels. This leaves WoC art educators/scholars vulnerable to systemic inequities in ways that our White colleagues are not.[104] In order to take action-oriented steps toward institutional change for the field of art education, what must first be acknowledged is the lack of sophisticated understanding of systems of domination and its broad reach within the world of art, in general, and within art education specifically. It is only then that strategies for addressing and diminishing systemic oppression can be accomplished. It would require a look at who sets the policy and what value-based investments are made to art education theoretical and curricular orientations and how these investments may be systemically prohibitive or inclusive of the artistic and scholarly production of WoC art educators.

At the peer level, to be a coconspirator means to speak up for a WoC who may be experiencing discrimination; a White coconspirator will less likely experience negative consequences for this action. This could take the form of speaking up during a meeting if a WoC has been interrupted or if someone has taken credit for an idea that has been developed by a WoC. While it is supportive to speak up for WoC, it does not mean to speak over them. Oftentimes, having a racialized privileged status creates blind spots for would-be White supporters. This privilege allows them to selectively decide when and how to “show up,” which diminishes and disrespects the rich contributions WoC bring to the table. An important and necessary factor in being a coconspirator is to listen as much as possible, instead of dominating the space. For transformative outcomes, these purpose-driven acts must be consistent and lifelong.

In this article, we forefront our stories and experiences because they challenge and problematize the historical and present discourse about feminism in art education that ignores us, yet claims to attend to issues specific to women. Research has identified the need for women scholars of color to write about their experiences and “to substantiate evidence that helps challenge the numerous stereotypes that negatively depict Black women and other minority members of the professorate.”[105] It is our responsibility to write ourselves into the feminist discourse in art education. This article seeks to do just that.

Black women and WoC need to find their own “homeplace,”[106] or site of resistance, in art education. hooks suggests, “Black women resisted by making homes where all black people could strive to be subjects, not objects, where we could be affirmed in our minds and hearts despite poverty, hardship, and deprivation, where we could restore to ourselves the dignity denied us on the outside in the public world.”[107] With this in mind, we better recognize that as WoC we should and can create our own space, developing new research and methodologies that support and appreciate our embodied experiences. Further, we need to commit to and lean on theoretical and conceptual frames that support and prioritize our multiple jeopardies.[108]

Female faculty of color have managed to survive, thrive, and achieve in the academe by employing a number of creative strategies to overcome obstacles. Our hope is that this article serves as a powerful literary tool that opens the possibilities for more WoC to share their narratives and resist oppressive forces that limit (or erase) our identities in White-dominated fields. In her public conversation with Beverly Guy-Sheftall, Thomas confidently asserts, “It’s not my job to make you feel good about your Whiteness and explain my Blackness.”[109] We share Thomas’s sentiments, and thus, our reason for writing this article was not only to offer implications to the field. With this trioethnography, we also wanted to share an inside look into our world in a way that our authentic voices would be heard and considered. We wanted to identify and name the problem behaviors that continue to silence us. Finally, what we shared here is but a glimpse into how we, three WoC in White academic spaces, survive; through finding out who our friends are and who they are not, building coalitions, relationships, kinship,[110] and loving each other. “It’s radical to love Black women. It’s radical for it [the love] to be seen.”[111]

Acknowledgments

The authors of this article are listed alphabetically. The author order does not represent the level of contribution. All authors contributed to the conceptualization and writing of this article equally from beginning to end. For us, our decision to order the authors alphabetically emphasizes the way we value process and equity, rather than a system of power. Specifically, we define “contribution” not only as pen to paper, or research hours, but as emotional support to each other when needed, even for issues outside of this article. Those lived experiences unequivocally contributed to this article. The article was produced over months of long girlfriend to girlfriend chats via video conferences, multiple manuscript read-aloud sessions, late night and early morning text messages, and, at times, some inappropriate, off-topic voice messages. Thus, author order only represents the authors’ names, not their “contribution” to this work. In addition, we give love and thanks to Esha Janssens for the beautifully designed images of our dialog. She captured the free-flowing spirit of our conversation, and symbolically, through different shades of brown, she illustrated the diversity in our Black and Brown voices.

1. Sean Landers, “Mickalene Thomas,” BOMB Magazine, July 11, 2011. https:// bombmagazine.org/articles/mickalene-thomas-1/.

2. Lynn Gailbraith and Kit Grauer, “State of the Field: Demographics and Art Teacher Education,” in Handbook of Research and Policy in Art Education, edited by Elliot Eisner and Michael Day (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers, 2004), 415–37.

3. Rachel Alicia Griffin, “Cultivating Promise and Possibility: Black Feminist Thought as an Innovative, Interdisciplinary, and International Framework,” Departures in Critical Qualitative Research 5, no. 3 (2016): 1–9.

4. Jennifer C. Nash, “Home Truths on Intersectionality,” Yale Journal of Law and Feminism 23, no. 2 (2011): 225–470.

5. Gloria Anzaldua, Borderlands: La Frontera, The New Mestiza (San Francisco, CA: Aunt Lute Books, 1997); Patricia Hill Collins, Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment (New York, NY: Routledge, 1990); Brittney Cooper, Eloquent Rage: A Black Feminist Discovers Her Superpower (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2018); Kimberle Crenshaw, “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics,” The University of Chicago Legal Forum 140 (1989): 139–67.

6. Joni Boyd Acuff, “Black Feminist Theory in 21st Century Art Education,” Studies in Art Education 59, no. 3 (2018): 205.

7. Patricia Hill Collins, “Black Feminist Thought as Oppositional Knowledge,” Departures in Critical Qualitative Research 5, no. 3 (2016): 133–144; Crenshaw, “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics,” 139–67; Nash, “Home Truths on Intersectionality,” 225–470; Kristin Waters, “A Journey from Willful Ignorance to Liberal Guilt to Black Feminist Thought,” Departures in Critical Qualitative Research 5, no. 3 (2016): 108–15.

8. Lori Walkington, “How Far Have We Really Come? Black Women Faculty and Graduate Students’ Experiences in Higher Education,” Humboldt Journal of Social Relations 1, no. 39 (2017): 51–65.

9. Joe Norris, Richard D. Sawyer, and Darren E. Lund, Duoethnography: Dialogic Methods for Social, Health, and Educational Research (Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press, 2012); Rick Breault, Raine Hackler, and Rebecca Bradley, “Seeking Rigor in the Search for Identity: A Trioethnography,” in Duoethnography: Dialogic Method for Social, Health, and Educational Research, edited by Joe Norris, Richard D. Sawyer and Darren Lund (Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press, 2012), 115–36; Gloria J. Wilson and Pamela Lawton, “Critical Portraiture: Black/Women/Artists/Educator/Researchers,” Visual Arts Research 45, no. 1(2019): 83–9; Gloria J. Wilson and Sara S. Shields, “Troubling the ‘WE’ in Art Education: Slam Poetry as Subversive Duoethnography,” Journal of Social Theory in Art Education 38, no. 1 (2019).

10. Breault, Hackler, and Bradley, “Seeking Rigor in the Search for Identity: A Trioethnography,” 115–136.

11. Homi K. Bhabha, The Location of Culture (New York, NY: Routledge, 1994).

12. Thomas, E. Barone, “Using the Narrative Text as an Occasion for Conspiracy,” in Qualitative Inquiry in Education, edited by Elliot Eisner and Alan Peshkin (New York, NY: Teachers College Press, 1990), 305–26.

13. Norris, Sawyer, and Lund, Duoethnography: Dialogic Methods for Social, Health, and Educational Research; Robert. E. Rinehart and Kerry Earl, “Auto-, Duo-and Collaborative-Ethnographies: ‘Caring’ in an Audit Culture Climate,” Qualitative Research Journal 16, no. 3 (2016): 210–24.

14. Norris, Sawyer, and Lund, Duoethnography: Dialogic Methods for Social, Health, and Educational Research,9.

15. William Pinar, “Currere: Toward Reconceptualization.” in Curriculum Theorizing: The Reconceptualists (Berkley, CA: McCutchan, 1975); William Pinar, “The Method of Currere: Essays in Curriculum Theory 1972–1992,” in Autobiography, Politics and Sexuality, edited by William Pinar (New York, NY: Peter Lang, 1994), 19–27.

16. Norris, Sawyer, and Lund, Duoethnography: Dialogic Methods for Social, Health, and Educational Research, 13.

17. John L. Jackson, Real Black: Adventures in Racial Sincerity (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2005), 17.

18. William Edward Burghardt Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk (New York: Dover Publications, 1994), 2.

19. Jackson, Real Black: Adventures in Racial Sincerity.

20. Melissa Crum, personal communication to authors, 2018.

21. Jackson, Real Black: Adventures in Racial Sincerity.

22. Laura Quiros and Beverly Araujo Dawson, “The Color Paradigm: The Impact of Colorism on the Racial Identity and Identification of Latinas,” Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment 23, no. 3 (2013): 288. doi:10.1080/10911359.2012.740342.

23. Ibid., 293.

24. Vanessa Lopez, "The Hyphen Goes Where? Four Stories of the Dual-Culture Experience in the Art Classroom,” Art Education 62, no. 5 (2009): 19–24.

25. Quiros and Araujo Dawson, “The Color Paradigm: The Impact of Colorism on the Racial Identity and Identification of Latinas,” 287–97.

26. Walkington, “How Far Have We Really Come? Black Women Faculty and Graduate Students’ Experiences in Higher Education,” 51–65. 27. Ibid., 54.

27. Ibid., 54.

28. Sarah Gibbard Cook, “Black Women’s Dilemma: Be Real or Be Ignored,” Women in Higher Education 22, no. 4 (2013): 19. doi:10.1002/whe.10446.

29. Cooper, Eloquent Rage: A Black Feminist Discovers Her Superpower.

30. Walkington, “How Far Have We Really Come? Black Women Faculty and Graduate Students’ Experiences in Higher Education,” 54.

31. Sheila T. Gregory, “Black faculty women in the academy: History, status, and future,” Journal of Negro Education 70, no. 3 (2001): 136.

32. Patricia Hill Collins, Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment, 2nd ed. (New York, NY: Routledge, 2009).

33. Walkington, “How Far Have We Really Come? Black Women Faculty and Graduate Students’ Experiences in Higher Education,” 51–65.

34. Freida High W. Tesfagiorgis, “In Search of Discourse and Critique/s that Center the Art of Black Women Artists,” in Black Feminist Cultural Criticism, edited by Jacqueline Bobo (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers, 2001), 147.

35. Tammy L. Henderson, Andrea G. Hunter, and Gladys J. Hildreth, “Outsiders Within the Academy: Strategies for Resistance and Mentoring African American Women,” Michigan Family Review 14, no. 1 (2010).

36. Collins, Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment, 300.

37. Gregory, “Black Faculty Women in the Academy: History, Status, and Future,” 124–38.

38. Social Sciences Feminist Network Research Interest Group, “The Burden of Invisible Work in Academia: Social Inequalities and Time Use in Five University Departments,” Humboldt Journal of Social Relations 39 (2017): 231. http://www.jstor.org/stable/90007882.

39. Andrew J. Fuligni and Sara Pedersen, “Family Obligation and the Transition to Young Adulthood,” Developmental Psychology 38 (2002): 856–68; Andrew J. Fuligni, Vivian Tseng, and May Lam, “Attitudes Toward Family Obligations among American Adolescents from Asian, Latin American, and European backgrounds,” Child Development 70 (1999): 1030–44.

40. Fuligni and Pedersen, “Family Obligation and the Transition to Young Adulthood,” 856.

41. Gregory, “Black Faculty Women in the Academy: History, Status, and Future,” 124–38.

42. Social Sciences Feminist Network Research Interest Group, “The Burden of Invisible Work in Academia: Social Inequalities and Time Use in Five University Departments,” 229.

43. Gregory, “Black Faculty Women in the Academy: History, Status, and Future,” 124–38.

44. Tiffany D. Joseph and Laura E. Hirshfield “‘Why Don’t You Get Somebody New to Do It?’ Race and Cultural Taxation in the Academy,” Ethnic and Racial Studies 34, no. 1 (2011): 123.

45. William A. Smith, Tara J. Yosso, and Daniel G. Solorzano, “Challenging Racial Battle Fatigue on Historically White Campuses: A Critical Race Examination of Race-Related Stress,” in Faculty of Color: Teaching in Predominately White Colleges and Universities, edited by Christine A. Stanley (Bolton, MA: Jossey-Bass, 2006), 299–327

46. Ibid., 301.

47. Acuff, “Black Feminist Theory in 21st Century Art Education,” 201–14.

48. Collins, Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment; Bell Hooks, Yearning: Race, Gender, and Cultural Politics (Cambridge, MA: South End Press, 1990).

49. Collins, Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment.

50. Ibid., 51.

51. Walkington, “How Far Have We Really Come? Black Women Faculty and Graduate Students’ Experiences in Higher Education,” 53.

52. Social Sciences Feminist Network Research Interest Group, “The Burden of Invisible Work in Academia: Social Inequalities and Time Use in Five University Departments,” 232.

53. Joseph and Hirshfield “‘Why Don’t You Get Somebody New to Do It?’ Race and Cultural Taxation in the Academy,” 121–141; Walkington, “How Far Have We Really Come? Black Women Faculty and Graduate Students’ Experiences in Higher Education,” 51–65.

54. Claude M. Steele and Joshua Aronson, “Stereotype Threat and the Intellectual Performance Test of African Americans,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 69, no. 5 (1995): 797–811.

55. Social Sciences Feminist Network Research Interest Group, “The Burden of Invisible Work in Academia: Social Inequalities and Time Use in Five University Departments,” 232.

56. Anzaldua, Borderlands: La Frontera, The New Mestiza.

57. Collins, Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment.

58. Ashley, Patterson, Valerie Kinloch, Tanya Burkhard, Ryann Randall, and Arianna Howard, “Black Feminist Thought as Methodology: Examining Intergenerational Lived Experiences of Black Women,” Departures in Critical Qualitative Research 5, no. 3 (2016): 58.

59. Peggy Davis, “Law as Microaggression,” Yale Law Journal 98 (1989): 1576.

60. Social Sciences Feminist Network Research Interest Group, “The Burden of Invisible Work in Academia: Social Inequalities and Time Use in Five University Departments,” 230.

61. Ibid., 230.

62. Joseph and Hirshfield “‘Why Don’t You Get Somebody New to Do It?’ Race and Cultural Taxation in the Academy,” 129–30.

63. Anzaldua, Borderlands: La Frontera, The New Mestiza.

64. Lisa Gail Collins, The Art of History: African American Women Artists Engage the Past (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2002).

65. Collins, The Art of History: African American Women Artists Engage the Past; Sander Gilman, “The Hottentot and the Prostitute: Toward an Iconography of Female Sexuality.” in Race-ing Art History: Critical Readings in Race and Art History, edited by Kymberly N. Pinder (New York, NY: Routledge, 2002), 119–33.

66. Maria del Guadalupe Davidson, “Black Silhouettes on White Walls: Kara Walker’sMagic Lantern,” in Body Aesthetics, edited by Sherri Irvin (Oxford University Press, 2016), 15–36.

67. Linda M. Chatters, Robert Joseph Taylor, and Rukmali Jayakody, “Fictive Kinship Relations in Black Extended Families,” Journal of Comparative Family Studies 25, no. 3 (1994): 297–312; Signithia M. Fordham, “Black Students’ School Success as Related to Fictive Kinship: A Study in the Washington, DC Public School System” (PhD diss., The American University, 1987); Gloria J. Wilson, “Fictive Kinship in the Aspirations, Agency, and (Im)possible Selves of the Black American art Teacher,” Journal of Social Theory in Art Education 37, no. 1 (2017): 49–60.

68. Wilson, “Fictive Kinship in the Aspirations, Agency, and (Im)possible Selves of the Black American art Teacher,” 50.

69. Na’im, Akbar, Know Thyself (Tallahassee, FL: Mind Productions and Associates, 1998).

70. Kumea Shorter-Gooden, “Multiple Resistance Strategies: How African American Women Cope with Racism and Sexism,” Journal of Black Psychology 30, no. 3 (2004): 406–25.

71. Collins, Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment.

72. Wilson, “Fictive Kinship in the Aspirations, Agency, and (Im)possible Selves of the Black American Art Teacher,” 49–60.

73. Stuart Hall and Paul du Gay, Questions of Cultural Identity (London: SAGE, 1996); Michael D. Harris, Colored Pictures: Race and Visual Representation (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2003).

74. Wilson, “Fictive Kinship in the Aspirations, Agency, and (Im)possible Selves of the Black American Art Teacher,” 49–60.

75. Robert Joseph Taylor, Linda M Chatters, Cheryl Burns Hardison, and Anna Riley, “Informal Social Support Networks and Subjective Well-Being among African Americans,” Journal of Black Psychology 27, no. 4 (2001): 439–63; Walkington, “How Far Have We Really Come? Black Women Faculty and Graduate Students’ Experiences in Higher Education,” 51–65.

76. Walkington, “How Far Have We Really Come? Black Women Faculty and Graduate Students’ Experiences in Higher Education,” 51–65.

77. Ibid., 58.

78. Henderson, Hunter, and Hildreth. “Outsiders Within the Academy: Strategies for Resistance and Mentoring African American Women.”

79. Carol B. Stack, All Our Kin: Strategies for Survival in a Black Community (New York, NY: Harper & Row, 1974); Beverly D. Tatum, “Racial Identity Development and Relational Theory: The Case of Black Women in White Communities,” Work in Progress, no. 63 (Wellesley, MA: Stone Center Working Paper Series, 1993); Wilson, “Fictive Kinship in the Aspirations, Agency, and (Im)possible Selves of the Black American Art Teacher,” 49–60.

80. Gregory, “Black Faculty Women in the Academy: History, Status, and Future,” 124–38.

81. Alfreida Daly, Jeanette Jennings, Joyce O. Beckett, and Bogart R. Leashore, “Effective Coping Strategies of African Americans,” Social Work 40, no. 2 (1995): 240–24.

82. Gregory, “Black Faculty Women in the Academy: History, Status, and Future,” 124–38; Walkington, “How Far Have We Really Come? Black Women Faculty and Graduate Students’ Experiences in Higher Education,” 51–65.

83. Robin DiAngelo, White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk about Racism (Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 2018).

84. Mickalene Thomas, “Mickalene Thomas in Conversation with Beverly Guy-Sheftall,” interview by Beverely Guy-Sheftall, Wexner Center for the Arts, Columbus, Ohio, September 13, 2018.

85. Patterson, Kinloch, Burkhard, Randall, and Howard, “Black Feminist Thought as Methodology: Examining Intergenerational Lived Experiences of Black women,” 59.

86. Wilson, “Fictive Kinship in the Aspirations, Agency, and (Im)possible Selves of the Black American Art Teacher,” 49–60.

87. Thomas, interview.

88. Davidson, “Black Silhouettes on White Walls: Kara Walker’s Magic Lantern,” 15–36.

89. Landers, “Mickalene Thomas.”

90. Henderson, Hunter, and Hildreth. “Outsiders Within the Academy: Strategies for Resistance and Mentoring African American Women.”

91. Thomas historicizes her work by acknowledging the historical art canon (Edouard Manet, Henri Matisse, and Romare Bearden), yet she pushes back on the White male gaze that is so familiar in art history, and counters the objectification of the female body by constructing a Black female gaze.

92. Collins, Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment; Patterson, Kinloch, Burkhard, Randall, and Howard, “Black Feminist Thought as Methodology: Examining Intergenerational Lived Experiences of Black Women,” 55–76.

93. Audre, Lorde, Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (Berkeley, CA: Crossing Press, 1984), 110.

94. Cooper, Eloquent Rage: A Black Feminist Discovers Her Superpower, 124.

95. Shannon K. McManimon and Casey, Zachary A., “(Re)beginning and Becoming: Antiracism and Professional Development with White Practicing Teachers,” Teaching Education 29, no. 4 (2018), 399.

96. Ibid., 396.

97. Bell hooks, Black Looks: Race and Representation (Boston, MA: South End Press, 1992), 35.

98. Acuff, “Black Feminist Theory in 21st Century Art Education,” 201–14.

99. Ibid.

100. Cooper, Eloquent Rage: A Black Feminist Discovers Her Superpower, 106.

101. Ibid., 103.