VOL. 20

Plotting the Black Commons

J. T. Roane

ABSTRACT

DOWNLOAD

SHARE

Since the mid-20th century, oil-dependent suburbanization and petrol agriculture have exacerbated the transformation and degradation of the lower Chesapeake ecotone—the unique meeting of water and land that constitutes the primary spaces of human and non-human living in Tidewater Maryland and Virginia.1 The meteoric growth of the metropolitan region between Baltimore to the north and Hampton Roads to the south endangers one of the nation’s most important hydrological systems as well as the human populations in rural, suburban, and urban settings who rely on these waterways for livelihood and leisure.

The case of the Anacostia River that runs a short course from Bladensburg, Maryland to one of the Chesapeake’s largest and most-endangered feeder rivers, the Potomac River, is exemplary of the degradation unchecked development threatens on the wider system.2 The Anacostia, which ends in the predominantly working-class Black community by the same name in Southeast Washington, DC remains among the most polluted rivers in the nation. Although Anacostia’s Black working-class communities, like many others in rural and urban settings in the region, continue to rely on the river for recreation and food, the development of highways, shopping centers, and suburban housing tracts have transformed the once densely forested area adjoining the river into a zone dominated by impervious surfaces and rapid runoff.3 As a result, the river is choked with heavy sedimentation and rendered poisonous by elevated concentrations of the automotive fuel byproduct, polynuclear aromatic compounds (PACs). Indeed, according to a 2001–02 study conducted by the Chesapeake Bay Field Office of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, between 50% and 68% of large brown bullhead catfish (Ameiurus nebulosus) in the Anacostia have liver cancer and between 13% and 23% had skin cancer from PACs.4 Suburban Maryland’s meteoric growth between 1950 and 2000 as well as its ongoing overdevelopment, has caused both the toxification of the Anacostia and the concentrated economic and social marginality of the people of Southeast Washington.5 The same infrastructures facilitating suburbanization and the attendant economic and social abandonment and isolation of poor Black residents of Anacostia also give rise to concentrated toxicity endangering the health of this introduced species of catfish, illustrating the intertwined nature of ecologies and human geographies.

Beyond the acute toxification over the course of the last several decades the degradation of the lower Chesapeake system and the exposure and vulnerability of local Black populations extends beyond oil-lubricated 20thand 21st-century development.6 In the colonial, antebellum, and postbellum periods, the primary shapers of Virginia’s and Maryland’s landscapes—its slave owning and post–Civil War elites—shaped the region through shared principles of dominion, or the notion of god-ordained exploitation and defilement for profit of the region’s land and water resources.7 The ideology of dominion granted the region’s ownership class the prerogative to transform what had in the 17th century been defined as a wilderness into an intricate plantation and industrial complex—various fiefdoms of paternalistic power centered in slave mastery organized to manipulate and exploit the ecotone for the extraction, processing, and shipping of profitable resources like wood, tobacco, and grain.8 This program of mastery had disastrous effects on the delicate brackish water systems; the land, plant, and land animal species; fish and other aquatic animals; and vulnerable human populations.9 For example, from the mid-18th century planters like Landon Carter of Sabine Hall in the Northern Neck of Virginia forced slaves to transfigure the interface of water and land through the construction of dams, the herding of domesticated animals at the expense of those indigenous to the region, and the displacement of forest biodiversity through the planting of cash crops to create a number of profitable market-oriented enterprises along the lower Chesapeake waterways. As Carter’s diary account illustrates, the effects of these transformations as well as proximity to distant places facilitated through transit routes along the growing Atlantic commerce set off various dislocations and epidemics that were shaped by environmental transformation. Carter reported chronic small-pox epidemics, flies pestilent to wheat “said to be sent into the Country by Mr. John Tucker of Barbadoes [sic],” rampant diarrheal diseases, and fits of ague or malaria overtaking the enslaved as well as his biological family after heavy downpours, likely exacerbated by deforestation. Enslaved, free, and later post-emancipation communities suffered the effects of these transformations as the malnourished laborers were forced to transform the landscape by filling swamps, rerouting and damning waterways, herding domesticated animals, and clearing forests.10 Although these landscapes have been transformed through several cycles of growth and retraction since the era when planters like Carter ruled, the descendants of enslaved communities inhabiting the region continue to inherit vulnerable low-lying bottoms as well as toxic land and waterscapes that are the culmination of this longer history of stewardship through mastery.

The historical and ongoing development of the region fits a pattern of characteristically (racial) capitalist landscape defined by radical, racialized inequality mapped over uneven, delicate ecologies. Yet embedded in the social–geographic fabric of the region is the dialectic contradiction posed by its most vulnerable inhabitants. Although the story of the Anacostia’s toxification is foremost one of exposure and vulnerability, within the cultural practices that lead Black residents in Southeast Washington, DC to fish and boat the waters is the seed of a new era beyond the toxic Chesapeake and the age of oil. These communities continue to self-fashion as individuals and as collectives through the practice of hybrid leisure cultures that incorporate elements and practices associated with rurality in the heart of the nation’s capital.11 They continue to share fish caught in the Anacostia and Potomac Rivers as currency of a local, small-scale community. While these expressions of the Black outdoors and reciprocity through fish by no means articulates a program legible under the rubrics of mainstream environmentalism usually oriented toward “saving” a species, a forest, or the planet, the contemporary Black outdoors culture in Washington, DC invokes the robust history and ongoing legacy of local communities’ efforts at self-creation and resistance carried out through intimacy and knowledge of the waterways, the forests, and the other “dark,” opaque, or hidden spaces these communities cultivated in the contexts of plantation and post-plantation landscapes.12 This tradition departs from the subject–object relations of mainstream environmentalism that adhere to the primary grammar of mastery even if exploitation is displaced with the desire to “save” a species, the rainforest, or the planet. Black environmentalism (for lack of a better term) retains subject to subject relations wherein fish and other resources from the local environment lubricate reciprocity between humans.

Given the intricate connections between local Black social life, the features of the region’s land and waterscapes, its delicate fisheries (e.g., blue crabs), and even its land animal populations (e.g., deer) the full express of Black social life is concomitant with the preservation and removal of hindrances to the processes of the wider biosphere. In other words, an engagement with these matters serves as a different epistemological basis for thinking about environmental history as well as the history of environmentalism. Specifically, though limited in their full expression given the constraints of urban living, these contemporary practices invoke the legacy of competing stewardship challenging enclosure that I term the Black commons. Through the fugitive practices of plotting enslaved and post-emancipation Black communities in the region created possibilities for survival, connection, and insurgency through the strategic renegotiation of the landscapes of captivity and dominion. “Plotting the Black Commons” recalls this history, examining Black communities’ engagement with practices of place and alternative figurations of land and water in the antebellum and post-emancipation periods. My formulation of plotting registers the actions of enslaved, free, and emancipated communities to create a distinctive and often furtive social architecture rivaling, threatening, and challenging the infrastructures of abstraction, commodification, and social control developed by white elites before and after the formal abolition of slavery.

Following Sylvia Wynter, the plot and plotting name the various iterations of a cosmological, geographic, and social outlook with material and political manifestations, whereby captive Black communities renegotiated the terrain of radical exploitation and totalizing social control envisioned by slave masters and later turn of the century urban developers and boosters. As Wynter describes in the context of the Caribbean, the plot was constituted foremost through a parcel of land given to the enslaved by planters “on which to grow food to feed themselves in order to maximize profits.” On the other hand, the provision ground in the Chesapeake, like its counterparts in the women’s market societies in the Caribbean, rendered “captive maternals” as the primary progenitors of a critical body of ecological knowledge that created epistemic possibilities for alternative modes of land and water stewardship.13 The plot allowed “African peasants transplanted” to the plantations of the Americas to transpose “all the structure of values that had been created by traditional societies of Africa” by which the “land remained the Earth—and the Earth was a goddess; man used the land to feed himself; and to offer first fruits to the earth; his funeral was the mystical reunion with the earth.” In turn, the plot incubated “traditional values—use values.”14 The plot or provision ground thus offered “the possibility of temporal and spatial control” and functioned as a “semi-autonomous space of cultural production … imbued with both a sense of … burden and a sense of creative possibility.”15

The plot/plotting has a number of distinct and overlapping registers in the context of this article’s account of the lower-Chesapeake’s historical development. Foremost the plot signifies the space of the body’s interment after death. Sometimes the site of the elaborate funeral, and more often the site of unremarked burial held in the memory of loved ones, the plot as a burial ground serves as an entry into the broader social architecture articulated by plotting. Plots for the dead signal a primary mode of organizing community, anchoring the present through the past within the grooves of a landscape. For people without the means to secure estates or other monuments that signify their importance or connection, the site of the plot is endowed all the more with significance. As well, funerals in their seriality marked time for rural and urban Black communities alike. Because they were one highly visible and thus commonly discussed manifestation of Black communities’ efforts to maintain different visions for the interface between the social and spiritual realms, (perhaps ironically) funerals serve as an index of the cultural complex the area’s Black communities used to negotiate alternative visions of life, the earth, and the divine. Derived largely from syncretized forms of West African mourning acts, enslaved Africans created new forms as their epistemological and cosmological frameworks were remixed and transformed to deal with disproportionate physical death as well as the condition of radical social alienation in the emergent geography of the Chesapeake.16 Funerals and the plot as a site of burial evidence Black social life asserted despite the ongoing anti-Black environmental catastrophe defining plantation and post-plantation society in the region. In the context of the plot as a site of burial, local Black communities ritualized enactments of social life refiguring death and the outdoors as sites for recalling ancestry and for unsettling white supremacist capitalist exploitation of the land and Black people alike.

Second, the plot signifies the garden parcel, the gendered and gendering space in which enslaved Black women and other captive maternals were required to perform reproductive labor critical to the maintenance of the enslaved population. On the one hand, the plot as garden parcel further taxed the labor of enslaved communities by forcing them to use the time after hard labor to augment their diets. Yet, the plot as garden space served as a space for the enslaved to reproduce visions for land usage organized through use value—or as spaces sustaining biological and social existence, rather than land or water resources to aggressively work for profit.

Third, the plot signifies the extension of these ongoing visions of use value into the dark ecologies of the forest and over the region’s waterscapes. The maintenance of values and value in use in order to make biological and social existence possible incubated a vision of the wider landscapes whereby procuring extra food not provided by slave owners bled into more subversive “taking of liberties” among the enslaved. Slaves extended the extra labor of hunting and fishing into subversive forms of leisure that often drew them into conflict with the logics of mastery and which pushed them to remap plantation ecologies outside the landscapes of domination defining plantation geographies.

This leads to the final designation of the plot in this article. The plot signifies insurgent cartography whereby enslaved and freedpeople used the other modes of plotting to articulate geographic identities laden with epistemological possibilities and horizons for the future outside the parameters of white dominance and control and through the ecstatic, beyond the theology of dominion. For enslaved communities and post-emancipation communities the various iterations of the plot often disrupted mastery and efficiency in terms of labor discipline, control, and dominion and required the articulation of a unique set of paths, hiding spots, and techniques of anti-surveillance and weaponization. This aspect of the plot suggests that all the iterations of the plot developed alongside and in response to the forms of surveillance and punishment that co-evolved to contain them. The plot as hidden time and space expressed in the outdoors invokes the opacity of Black sociality. By hiding in plain sight and developing social–geographic grammars unintelligible even as outsiders watched, the enslaved rendered Black holes in the landscapes of ostensible total control, mastery, and surveillance, providing the very basis of the Black commons. Black holes represent strategic blurring, aphasia, and unaccounted-for space by which and within which enslaved and post emancipation Black communities created and perpetuated underground social life while the Black commons represents the elaborated sense of place outside mastery expressed through human to human connection within the delicate ecologies of the wider biosphere.

Taken together the various interlocking aspects of the plot erected a Black commons whereby enslaved, free, and post-emancipation communities extended their notions of value and values that ran anathema to capitalist enclosure and mastery. The plot/plotting in this context is an especially powerful example of Black social life lived in Black holes that is enacted in intimate relationship with death itself. The plot as a complex produced significant forms of Black sociality in the midst of an excess of loss, grief, and violence associated with death. The plot as burial site, garden parcel, and larger visions of de-commodified water and landscapes served as the basis of a local Black radical ecological tradition of which Black women, the elderly, and fugitives were the primary progenitors of epistemologies and cosmologies that subtly or explicitly challenged mastery.17 The Black commons formed out of the evolving manners by which enslaved Africans and their descendants created alternative modes of place through their cosmologies and forms of social life. They defied their simple thing-ification, reclaimed social bonds among those constitutionally configured as sub-human, reimagined the divine outside of mastery, and articulated the basis for a different mode of human–earth connection. Evolving in dialectic with mastery and dominion—or biblically justified total control—enslaved and post-emancipation communities claimed and created communal resources within the interstices of plantation ecologies.

Plotting and Slavery

Given the centrality of disproportionate death as part of the mundane and quotidian effects of racial capitalism from its consolidation in the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, funerals and practices of mourning have served as dense sites of cultural memory through which Black communities engendered and transmitted their visions for an alternative interface among humans and between humans and the earth. Funeral rites, mourning practices, and spiritualized efforts to ward off death or embracing it have signified on the deep metaphors of human and earth reciprocity that diasporans perpetuated as they grafted African cosmologies over the unfamiliar grooves of the Chesapeake’s topography, and serve as the primary “plot.”

As the literature in Africana Studies bears, death, mourning, and the stylized cultural event where these things come together, the funeral, have remained central to Black culture and politics in the United States and in the wider African diaspora. In part, this is a reflection of the intergenerational proximity to trauma and death Black communities have faced. As Karla F.C. Holloway writes, Black “vulnerability to an untimely death in the United States affects how Black culture represents itself.”18 According to Sharon Holland, “[i]n existential terms, knowledge of our own death determines not only the shape of our lives but also the culture we live in.”19 Writing about the Jamaican context, Vincent Brown posits that the dead always have “enjoyed an afterlife” in the cultures of the Diaspora, often animating what he terms a “mortuary politics.”20 As Dagwami Woubshet theorizes from spirituals, Black mourning practices belie the simplistic dichotomy outlined in psychoanalysis between normative mourning and its “pathological” forms, like melancholy. Black mourning is marked by what Woubshet terms “compounding loss” to underscore “the serial and repetitive nature of the losses [Black communities] confront,” ultimately also transforming the grammar of life itself.21

As early as the 1660s, enslaved Africans along the estuaries that cut Southern Maryland and Tidewater Virginia had begun to make alternative claims on the region’s emergent social geography. In both the 1663 Gloucester County plot and in the more famous 1666–67 Bacon’s Rebellion, enslaved Africans joined indentured servants from Europe in seeking to overthrow Virginia’s colonial government. However, it was in 1687 that enslaved Africans on the Virginia side of the Potomac River in Westmoreland County plotted the young colony’s first all-Black rebellion. In part explained by increasing separation that the Virginia Assembly legally enacted after 1667, the Assembly’s legal response to the foiled 1687 plot draws us back to an originary moment in the articulation of a politics of life in the face of death among the regions’ first Black inhabitants. As the respondent of the Executive Council wrote in the aftermath of the rebellion:

And this Board having [sic] Considered that the great freedome [sic] and Liberty that has beene [sic] by many Masters given to their Negro Slaves for Walking on broad on Saterdays [sic] and Sundays and permitting them to meete [sic] in great Numbers in makeing [sic] and holding Funeralls [sic] for Dead Negroes gives them the Opportunityes [sic] under pretention of such publique [sic] meetings to Consult and advise for the Carrying on of their Evill [sic] & wicked purposes & Contrivances, for prevention whereof for the future, It is by this Board thought fitt that a Proclamacon [sic] doe [sic] forthwith Issue, requiring a Strickt [sic] observance of Severall [sic] Laws of this Collony relateing [sic] to Negroes, and to require and Comand [sic] all Masters of families having any Negro Slaves, not to permitt [sic] them to hold or make any Solemnity or Funeralls [sic]for any deced [sic] Negros [sic].22

This passage refers back to Virginia’s earlier “Act of 1680 on Negro Insurrection” which prohibited “feasts and burials” among the enslaved and illustrates that leading colonists developed paranoia about the social life of the people they tried to render into fungible commodities through social death.23 The explicit naming of funerals in both 1680 and 1687 as a site of conspiracy also substantiates the maintenance of an alternative cosmological and political force among the enslaved.24 Funerals served as sites in which traditional communal rites were remixed and repeated. The funeral was a site of self-conscious intergenerational communal fashioning enacted by the enslaved whose existence was otherwise flattened into fungible, sub-human laborers in the service of the emergent Atlantic economy. Many aspects of Black funerals were derived from West African funerary practices.25

Funerals and death grounded Black cultural life in a set of often-clandestine sites from the Chesapeake’s origins as a part of the nascent European colonial complex. For example, archeologists have excavated a series of subterranean floor pits from the 18th century that historians describe as being used to hide various delegitimized effects of transplanted African culture, including ancestral altars.26 Africans in the Tidewater maintained covered and hidden earthen holes in the quarters that they may have used to honor the dead and this was part of the foundations of a kind of a hidden, sometimes hidden in plain sight, alternative Black landscape.27 As historians of slavery illustrate, Black landscapes served as a kind of fugitive geography and were comprised of a “system of paths, places, and rhythms that a community of enslaved people created as an alternative, often a refuge, to the landscape system of planters and other whites” created a “largely secret and disguised world.”28 Spaces of engaging and honoring the dead were a fundamental aspect of the plot helping to articulate the grammar of Black social life.

The centrality and importance of death and funerals in a context of ongoing, antiBlack environmental catastrophe and as part of the wider politics and episteme of the plot as a central place within a Black landscape grounded continuity in the region’s Black cultural life. Critically, Black communities continued distinctive spatial practices that undergirded Black communal survival as well as explicit challenges to the logics of racial slavery and plantation geography. This included the continuation of the plot, its extension into a Black Commons, and also orchestrated fugitive connections between enslaved people on both banks of the Potomac. For example, in his 1937 Works Progress Administration (WPA) narrative, James V. Deane, a formerly enslaved resident of Baltimore, described life on a large plantation along Goose Bay, an inlet of the Potomac River, in Charles County, Maryland where he was raised in the antebellum period. Deane described a distinctive Black geography that denies the bounded and strict cartography instituted through the regime of real property and chattel—“over 10,000 acres” and “a large number of slaves, I do not know the number”—that was the primary source of white patriarchal power. Critically, the Black geography of the plantation overlaid the dominant layout and infused it with other kinds of spiritual and social significance.29

According to Deane, there were a number of activities that were not sanctioned by the owners of the plantation that built a social world alternative to the edicts of dominion. The alternative Black landscape Deane described grounded other kinds of potentially dangerous practices that served as the infrastructure of a different order. As Deane relayed, the enslaved convened with the enslaved from plantations across the Potomac in Virginia: “When we wanted to meet at night we had an old conk, we blew that. We all would meet on the bank of the Potomac River and sing across the river to the slaves in Virginia, and they would sing back to us.”30 While this kind of connection through sound was not a call to arms against the enslavers, per se, it created the potential for secretive and fugitive social connections that endangered the vision of total control proposed in the legal fictions of the enslavers.

Deane also charted continuity in the plot and its wider significance for materially anchoring the less tangible elements of an alternative Black landscape. According to Deane, the enslaved “had small garden patches which they worked by moonlight.” Although there was an official physician charged with ensuring the health and productivity of the enslaved, as he described, “the slaves had herbs of their own, and made their own salves,” which they grew in their plots.31 While the record leaves no evidence of the full parameters of this alternative way of seeing the landscape, it is clear that the enslaved created and maintained a distinctive interpretation of space from a shared vision for social and cosmological integrity. Indeed, these served as an important counterpoint for the nascent biomedical prescriptions for health and the ideologically laden religion of the enslavers that confined them to a “slave gallery” in the church where they learned the “Lord’s Prayer and the catechism.”32

Deane also described another element of the plot as a site of the continuation of a different kind of cosmological and social vision and thus also a source of Black vitality: a vision for a Black commons. As he relayed, “My choice food was fish and crabs cooked in styles by my mother.” Here it is significant that Deane’s preferred foods were products of the delicate watershed and brackish ecologies that constitute the primary contours of region and that it was prepared by his mother. Food that the enslaved independently procured from the waters of the Potomac and similar estuary environs as well as the labor of Black women in the processes of food production and preparation served the currency for forms of insurgent Black social life and intergenerational affection in the face of dominion that rendered the master class lord of Black bodies, and resistance as sickness.33

Black communities forged around the products of a unique and threatened ecology a vision of social life, vitality, and cosmological integrity that prompts us to think about the significance of the commons and the reproductive labor of Black women in the forwarding of Black resistance. Generally, Black communities are either collapsed into the environment on the one hand, or pictured as unconcerned about the preservation of the biosphere on the other. Enslaved Black people and their descendants, over whom the institution cast a long shadow, navigated the precarious line between acting directly as the agents of ecological destruction and working the landscape to carve out the contours of an entirely different kind of social order. As the enslaved asserted their vision for the commons, their labor was also forcibly used, mobilized, and extracted for the rapid colonization of the land and its devastation upon the rivers and streams that constitute the Chesapeake, rendering the Black commons Deane described fleeting, tenuous, and contradictory. And yet it is an alternative history of the region in a critical era of the transformation of the land and waterscapes that is a usable history in our moment of rapidly declining Bay ecology.

For example, when Washington, D.C. was established as the capital in 1795, the Anacostia was navigable to Bladensburg, Maryland and was reportedly one mile wide and twenty feet deep at the place where it meets the Potomac River. Within a century, land clearing and cultivation effected primarily by the forced labor of the enslaved drove rapid sedimentation and shoaling that transformed a river once teeming with life into a slow and increasingly toxic sludge in the 20th century as I discussed in the introduction.34 While the enslaved were among the primary agents used in the clearing of this land for cultivation and urban development, they anchored in the phenomena of death and the plot a vision of social and cosmological integrity that included the Black commons, a furtive and sometimes failed challenge to dominion.35

On his journey through the region to the Cotton Kingdom further south, noted writer and landscape architect Frederick Law Olmstead also observed that the landscape he encountered between Maryland; Washington, DC; and Virginia. Olmstead described a landscape of capitalist redundancy, environmental degradation, and ruinate—or parcels of land that had once been cultivated but which had subsequently lapsed back into bush or forest.36 As he wrote: “Land may be purchased, within twenty miles of Washington, at from ten to twenty dollars an acre. Most of it has been once in cultivation, and having been exhausted in raising tobacco, has been, for many years, abandoned and is now covered by a forest growth.” Olmstead advocated the return of this land to productivity, arguing that “by deep plowing [sic] and liming, and the judicious use of manures, it is made quite productive.” While the kinds of technologically enhanced farming practices Olmstead advocated would not emerge in large measure until the 20th century with the recapitalization of the region’s agriculture as part of the truck-farm production for a growing market in Washington, these kinds of interventions would have disastrous effects on the estuary environments of the wider Potomac and Chesapeake basins.

An outsider, Olmstead also unwittingly captured elements of a fugitive Black landscape: of individual and collective renegotiations of the plantations’ geographic parameters to carve out Black social life. Fugitive Black landscapes of the antebellum period were often confined, as Katherine McKittrick describes through her reading of Harriet Jacobs’s escape narrative. Yet, as McKittrick elaborates, they were also the points of possibility for acts of rebellion including an effective escape.37 We should view these fleeting geographic alternatives as part of a wider if not totally recoverable vision of social–cosmological integrity, cultural continuity, and futurity, as well as more eventful attempts to subvert dominion.38

On visiting a plantation in Maryland, just north of Washington on December 14, 1852, Olmstead observed the dominant geography and also got a taste for the fugitive practices of Black culture in their “rudeness.” As he penned, “The residence is in the midst of farm, a quarter of a mile from the high road—the private approach being judiciously carried through large pastures which are divided only by slight, but close and well-secured wired fences.” “The kept grounds,” euphemistically disarticulated from the subjects doing the keeping, “are limited, and in simple but quiet taste; being surrounded only by wires, they merge, in effect, into the pastures. There is a fountain, an ornamental dovecote, and ice-house, and the approach road, nicely graveled and rolled, comes up to the door with a fine sweep.”39

Once Olmstead reached the gate, an enslaved person who remained unseen interrupted the idyllic scene. As Olmstead transcribed, fabricating Black speech, “Ef yer wants to see master, sah, he’s down thar—to the new stable.” Olmstead continued: “I could see no one.”40 For Olmstead, this kind of Black obstinacy, the enslaved person’s refusal to be seen and thus accounted for, was part of the ineffectiveness of the institution of slavery. Olmstead used these kinds of interruptions in social–geographic order, or Black holes, as a point of comparison for the system of land tenure on the part of an “industrious German” without slavery. However, given the totalizing control over land and life intimated in the ideology of dominion, the ability to remain yet unseen was a point of possibility within a continuum of political action and within a fleeting but present fugitive Black landscape. As Simone Brown has developed in a different context, a Black politics of Black countersurveillance or “dark sousveillance” resisted the optics of total control that masters fantasized was possible.41 Through the refusal to be seen, hiding in plain sight, or doing things beyond the reach of surveillance enslaved Black people opened critical and sometimes strategic gaps in the cartography of mastery. Black holes name this strategic invisibility or hiddenness Black communities practiced in order to create the possibilities for the Black commons and a wider world otherwise.42

Moving further South along his journey, Olmstead described a feature of Richmond’s Black landscape, which, as I describe above, remained an important site of Black cultural practice and continuity, the funeral. In addition to being struck by the “decent hearse” he was surprised to find that among the twenty or thirty women and men in the procession, “there was not a white person.”43 Upon arrival to the grounds, Olmstead noted that the burial ground was already inhabited by another group of enslaved “heaping the earth over the grave of a child, and singing a wild kind of chant,” and attesting to the ways that premature death continued to weigh on Black communities.44

Once the procession reached the final resting place, Olmstead observed Black communities engaged in a distinctive mourning that remained unintelligible to him as an outsider and which must be considered as part of the wider practices of a distinctive cosmological universe in and by which Black communities maintained the grammar of the Black commons. While there can be no return to the words and the full meaning of them within the universe of the mourners, the fact that they were closed to an outsider and well rehearsed to insiders illustrates the continued importance of funerals as spaces of cultural defiance, limited self-fashioning, and furtive resistance in the face of processes of unmaking that commodifying humans presupposed. Funerals represented Black holes, not necessarily as invisible or hidden places but rather as strategically unrecognizable collective forms unnamable in the purview of the gaze of an outsider that doubled as sites of resistance. Here, resistance does not signify open rebellion that threatens in total the civil and social order, but rather the points and places of possibility for Black life and futurity outside the limiting definition prescribed by the juridical rendering of Black people as chattel. For example, the well-dressed orator and officiator of the funeral rites began to speak, prompting Olmstead to write, “I never in my life, however, heard such ludicrous language as was uttered by the speaker. Frequently I could not guess the idea he was intending to express.” Later, Olmstead described the singing of a hymn, “a confused chant—the leader singing a few words alone, and the company then either repeating after him or making a response to them. … I could understand but very few of the words. The music was wild and barbarous.” Although the space of this article does not permit further exploration, I must note that the contrast between Black unintelligibility as a practice related to the plot and the Black commons, and Olmsted’s architectural work to render landscapes more easily traversable and accessible as part of the ongoing practices of dominion and enclosure are stark and require further investigation.

The ability of the enslaved to convey intelligible messages within the community and not to outsiders indexes the maintenance of an infrastructure in a fleeting fugitive Black landscape through the space of the funeral and through the rituals of the body’s internment. Local enslavers tacitly acknowledged as much. As Olmstead observed, “No one seemed to notice my presence at all. There were about fifty colored people in the assembly, and but one other white man besides myself. This man lounged against the fence, outside the crowd, an apparently indifferent spectator, and I judged he was a police officer, or some one [sic] procured to witness the funeral in compliance with the law which requires that a white man shall always be present at any meeting, for religious exercises, of the negroes.”45 While the songs and spoken words at the heart of the funerary rites practiced by the enslaved remained opaque to Olmstead, white Virginians recognized the continued threat posed in the fugitive sonic world mapped in the dirges. They had, as I have illustrated, enshrined the strict surveillance of Black funerals by white observers in the law during the colonial period. The inside world of the enslaved and the surveillance of slave mastery converged here at the site of the funeral since masters understood the threat the funeral rites posed even without having full access to the contours of the rituals and ceremony. Olmstead, however, remained a total outsider.

Within the context of death, depravation, and starvation, the enslaved drew on the resources of the plot as stolen time, as the garden parcel, and as the watery commons of the region to supplement meager diets taxed by the physical intensity of plantation labor. As James L. Smith recalled in his 1880 narrative, slave owners allotted enslaved men a weekly provision of “a peck and a half of corn meal, and two pounds of bacon” while women and children were given “a peck of meal, and from one pound and a half to two pounds of bacon.” According to Smith slaves supplemented these starvation rations with fish, crabs, and oysters they fished from the region’s various waterscapes, the meat of “coons and possums” they hunted at night, and with sweet potatoes and other vegetables they grew in the small plots they maintained. On the one hand, slave masters’ paltry provisions forced the enslaved to feed themselves, enhancing the abstraction of value from slaves by forcing them to absorb the cost in terms of labor and time of reproducing themselves.46 On the other hand, working the plot brought slaves into direct confrontation with the vision of temporal order and labor discipline, what La Marr Bruce calls Western Standard Time, enslavers sought to enforce.47 As Smith recalled, “One night I went crabbing and was up most all night; a boy accompanied me. We caught a large mess of crabs, and took them home with us. The next day I had to card for one of the women to spin, and, being up all night, I could hardly keep my eyes open; every once in a while I would fall asleep.” Crabbing in order to supplement the inadequate diet provided by slave masters in the first instance enhanced the exploitation and taxing of the life energy of the enslaved, yet the effort to live and to extend unsanctioned social existence brought Smith into conflict with mastery. Through these kinds of fugitive relationships with the plot, antebellum and postbellum Black communities forged alternative claims on land and water resources organized primarily around the Black commons and through the practices of what I term fugitive commensality—the unsanctioned and often illicit procuring, preparation, and sharing of food. Critically, fugitive commensality required active imagination and work since under slavery and the period of Jim Crow’s consolidation, starvation served as an essential technique of discipline, control, and punishment while feasts served as a compulsory and coercive form of glut that enhanced the quotidian violence of depravation. In spite of violence and coercion through nutrition, however, Black communities appropriated feasts, sometimes formal, sometimes furtive, to create a unique social grammar through formal as well as unsanctioned and illicit collectivity around food.

Critically, if commensality provides the basis of human socialization and community, it is also embedded within a wider ecology—the landand waterscapes people use and cultivate to make eating possible.48 Blurring discrete lines between human communities, non-human species populations, and the environment, commensality includes not only an interface between people but also between people and the wider biosphere. Critically, through the technologies of fugitive commensality in relation to the Black commons, these communities partially indigenized their relationships with the land- and waterscapes, forwarding visions of use-value despite enclosure and commodification. In quotidian practices of procuring fish, hunting, planting plots, and foraging in forests for curatives and other plant life with cosmological significance, these communities practiced the Black commons. Black communities created, inhabited, and manipulated Black holes in order to create the conditions for Black social life whereby Black social life is understood as “fundamentally the register of Black experience that is not reducible to the terror that calls it into existence but is the rich remainder, the multifaceted artifact of Black communal resistance and resilience that is expressed in Black idioms, cultural forms, traditions” and geographic practices.49

Slaves used the plot as stolen time to engage in their own independent visions of self, family, and community.50 In a system that sought to atomize slaves and render them fungible, the plot as an insurgent relation to space and time brought the possibilities for an otherwise. Insurgent here signifies a spectrum of infra political action on continuum with outright defiance. While the plot as the black hole of stolen time and space most often did not disrupt the larger institution of slavery like it did in Northampton, Virginia during Nat Turner’s 1831 rebellion, it provided space for individual slaves and freed people to renegotiate the terms and conditions of plantation labor and discipline and tore openings into the artifice of master time wherein enslaved and postemancipation communities created affirmative collective identities in spite of the violence, depravation, and social death that were the hallmarks of the institution and its afterlives. As a number of people who were enslaved during the antebellum period described, the plot as stolen time bled into the practices of the Black commons, creating the conditions for leverage along what Joy James calls “The Black Matrix”—an alternative political fulcrum “shaped by triad formations in racial rape/consumption, resistance, and repression in a renewable cycle of fight, flight, and fixation.”51 Plotting the Black commons allowed enslaved communities to rupture the spatial and temporal logics of captivity.

The Black commons was a function of what many masters understood as “Nigger day-time” or the space and time for activities ranging from those that were tacitly sanctioned by masters like gardening to those that were illicit, like engorging oneself on a stolen hog.52 Manipulating the optics upon which mastery depended, slaves used the cover of night as well as the alternative knowledge of forested and swampy landscapes to forge an infrastructure of hidden paths and furtive geographies that helped give shape to the Black commons. Runaways as well as individuals seeking alternatives to violent former masters in the wake of slavery’s formal demise weaponized the infrastructure of dark paths through the forests and swamps of the region, to gain basic provisions in order to survive—the very precondition of leverage.

Minnie Fulkes recalled the weaponization of enslaved peoples’ knowledge of the terrain of captivity and their renegotiation through “darkness” of master time and the geographies of captivity to create fleeting autonomous spaces of prayer, ecstatic worship, and a radical reworking of Christian theology in the hands of slaves. She recalled the use of “a great big iron put at the door” slaves used to dampen the sounds of their worship and to prevent the old “paddy rollers” who “would come and horse whip every last one of them, just cause poor souls were praying to God to free ‘em from that awful bondage.” Fulkes also recalled the worshipers tying “grape vines an’ other vines across th’ road, den when de Paddy rollers come galantin’ wid their horses runnin’ so fast you see dem vines would tangle ’em up an’ cause th’ horses to stumble and fall. An’ lots of times, badly dey would break dere legs and horses too; one interval one ol’ poor devil got tangled so an’ de horse kept a carryin’ him, ’til he fell off horse and next day a sucker was found in road whar dem vines wuz wind aroun’ his neck so many times yes had choked him, dey said, ‘He totely dead.’ Serve him right ’cause dem ol’ white folks treated us so mean.”53

As Smith described, he along with other slaves in a twelve-mile or more radius used their intimate knowledge of the alternative pathways and the cover of darkness to hold prayer meetings and to engage in ecstatic community wherein as Aaliyah Abdur-Rahman describes regarding another context, “the black ecstatic pervades expressive forms as an abstractionist practice of conjuration that foregrounds the importance, the timelessness, and exuberant pleasures of black communion.”54 As Smith recollected, “I remember in one instance that having quite [sic] work about sundown on a Saturday evening, I prepared to go ten miles to hold a prayer meeting at Sister Gould’s” where “quite a number assembled in the little cabin, and we continued to sing and pray till [sic] daybreak.” Smith described the lively worship experiences of these illicit prayer meetings as “almost indescribable” and in that intangibility as an “ecstasy of motion, clapping hands, tossing of heads, which would continue without cessation about half an hour.”55 While the ecstatic is not singularly liberatory, it rends an opening in the temporality and spatial dynamics of mastery and dominion—space for an “unruly structure and experience” that “operationalizes the limit, which it also perpetually violates and reforms.”56 Thus, while ecstatic prayer meetings did not necessarily dovetail into outward rebellion against mastery, the effect of timelessness and indescribability that Smith recalled temporarily suspended the subject–object relations governing plantation ecologies, edifying a competing schema for connection outside abjection.

Although the religion of the enslaved produced outward signs of docility, reinforcing mastery in the public transcripts, the experiences of the Black ecstatic facilitated through the plotting of the Black commons could also align with explicitly liberatory visions of the land and waterscapes wherein the enslaved and freedpeople saw these spaces as animate with power sufficient to end white domination. As Fulkes recalled these hidden spaces of the Black ecstatic were capable of producing theologies that if given full expression could take the negation of slavery to potentially revolutionary ends. While the post-1831 repression of enslaved and free Black people in Virginia and beyond limited antebellum rebellions, these spaces of hidden ecstatics continued to buttress a vision of the landscape anathema to mastery and dominion wherein God and nature served as arbiters of cosmic justice outside of white domination. Fulkes maintained this vision through emancipation into the 1930s when she revealed part of this vision to the WPA interviewer. According to Fulkes, the sublime—the landscapes wherein one might contemplate God, divinity, and nature—could also be invoked to destroy white oppressors. Fulkes told her interviewer quite candidly, “Lord, Lord, I hate white people and de flood waters gwine drown some mo.”57 Here an appreciation for the watery landscape doubles as a means of cosmic justice whereby white people will drown for the evils of their violence and violation against slaves, former slaves, and ostensibly free people.

In the context of plantations, the spaces of formally recognized Black social life were articulated within a complex terrain of deprivation and glut channeled and shaped by the calculations of exaction and extraction. Slave owners punctuated quotidian starvation with eventful feasting. Feasting like other moments of merriment helped planters exact further productivity and thus served as a tool of discipline helping enslavers to manipulate and draw nigh their affections of slaves despite the violent power they otherwise wielded. In the lower Chesapeake, these spaces, however, also served as spaces of Black gatherings or spaces “full of Colored people,” as Mrs. Fannie Berry recalled in later recollections of her wedding and reception in the parlor of a white mistress on Crater Road near Richmond, Virginia. Weddings and receptions acknowledged and supported by slave owners did not ensure the power of a legal contract to protect the relationships slaves built. Further, they evidence the matriarchal and patriarchal paternalism in response to the international discourses of abolitionism. As Berry remembered, “wasn’t no white folks to set down and eat before you.” “We had everything to eat you could call for” and where they could sing, dance square dances of their choosing. As Berry recalled through the refractions of memory, “Lord! I can see them gals now on that floor, just skipping and a trotting.” Although it is an expression blurring the lines between Black social life and the forced merriment Saidiya Hartman describes, the visions of fullness and abundance drew on the plot and the Black commons to articulate the feast as a fundamental if also vexed grammar of Black social–ecological life.58

The Black commons inspired alternative epistemologies, unfolding and forwarding vernacular wisdoms about daily life in relation to non-human species, natural events, the divine, and the wider features of the watery environment defining the region. Many of these remain embedded within the epistemic universe of their progenitors and do not necessarily correspond to modes of engaging the features of this landscape in ways directly accessible to people outside the parameters of these communities. As post-emancipation oysterman and fisherman Robert Slaughter recalled:

I tell you what I did once. My cousin and I went down to the shore once. The river shore, you know, up where I was born. While we were walking along catching tadpoles, minnows, and anything we could catch, I happened to see a big moccasin snake hanging in a sumac bush just a swinging his head back and forth. I swung at ’im with a stick and he swelled his head all up big and rared back. Then I hit ’im and knocked him on the ground flat. His belly was very big so we kept hittin’ ’im on it until he opened his mouth and a catfish as long as my arm (forearm), jumped out jest a flopping. Well the catfish had a big belly too, so we beat ’em on his belly until he opened his mouth and out came one of these women’s snapper pocketbooks. You know the kind that closes by a snap at the top. Well the pocket book was swelling all out, so we opened it, and guess what was in it? Two big copper pennies. I gave my cousin one and I took one. Now you mayn’t believe that, but it’s true. I been trying to make people believe that for near fifty years. You can put it in the book or not, jest as you please, but it’s true. That fish swallowed some woman’s pocketbook and that snake just swallowed him. I have told men that for years and they wouldn’t believe me.59

The Black Commons expressed a vision of Black resourcefulness that was manipulated by slave owners to maximize the profitability of water and land resources, but that was also often capitalized on towards ends at odds with the sense of social–spatial order on ante-bellum plantations. Runaways, whether engaging in full-scale marronage or the other smaller acts of running away whereby they renegotiated the conditions of their labor and living, the Black commons represented a tenuous, fleeting, and dangerous re-commoning of what the ownership class held to be their property. Runaways “lived in the woods of taking things such as hogs, corn, and vegetables from other folks’ farm.”60 This was quite dangerous as it risked the possibility of transport to the emerging plantation ecologies of the Deep South. As Harris recalled, “Well if dese slaves was caught, dey were sold by their new masters to go down South.”61 Though dangerous, the enslaved engaged forms of fugitive commensality, whereby they manipulated and weaponized their intimate geography plantations, especially of the spaces between them, to subvert the dictates and discipline of property and profitability and to express a vision for the land and water beyond dominion.

Postbellum Plotting

The formerly enslaved continued the primary anchors of their fugitive Black commons even as the Civil War shred the social–geographic fabric of Virginia and other portions of the region. Communities newly freed from the spatial constraints of plantations nevertheless forwarded elements of the Black commons to reimagine social life formally free of the fetters of slavery if not its reductive logics about the place of Blackness in the country. In the aftermath of formal freedom, the formerly enslaved remixed the cultural practices of the plot. Local communities absorbed the traditions of a larger stream of Black migrants from other parts of the South into the Chesapeake’s primary cities, including the nation’s capital. Here, I examine the continuance of the plot and the Black commons into the aftermath of formal emancipation.

In the aftermath of the Civil War, the Black commons again served as a tenuous and fleeting opening in the resources for the possibility for Black life on its own terms. As Fulkes recalled: “oh! it makes me shudder when I think of some slaves had to stay in de woods an’ git long best way dey could after freedom done bin’ clared; you see slaves who had mean master would rather be dar den whar dey lived.” The Black commons here is expressed as a furtive and tenuous infrastructure that created the material conditions of a primary aspect of wider Black politics: refusal. Here as Bulkes recalls, some of the formerly enslaved lived in the woods surviving off things they could find as well as contraband in the form of hogs or other stolen food. The Black commons served as a measure that allowed the enslaved to renegotiate their spatial and economic conditions, claiming a bare form of autonomy wherein some would rather face the elements and perhaps even death than to deal with the terror of former masters.

Urban Black communities constituted by the migration from various rural locations to industrial centers like Richmond and Baltimore or to the nation’s capital distilled the practices of alternative earth stewardship into the novel social infrastructures and institutions they created in slavery’s aftermath, despite their experiences with segregation, isolation, and enmity. Black communities in Washington, D.C. in particular recreated the city’s contours by melding the various and distinctive epistemes and practices that they brought with them from various parts of the rural, mill-town, and urban locations. In the process, they created a distinctive working-class Black culture and spatial practice that evolved by subverting, if not altogether disrupting, the visions forwarded by boosters, planners, and capitalists to govern the city through the lens of orderly development and sustained commercial growth.

Black communities continued to recreate the elements of the plot and the wider practice of the Black commons in new social–geographic forms. In 1864 an officer in a Michigan Calvary Regiment, George Alvord, wrote in defense of a small Black community that emerged near the Fairfax Seminary just across the Potomac from Washington in Virginia. Defending the new Black neighborhood against its removal, Alvord described one of the distinctive features of the community as its “little garden spots with vegetables yet in the ground.” He went on to say that he thought it “would be, in my opinion, rather hard to eject them from the premises at present.”62

Indeed, sowing a garden was of a practical nature as the practice remained a primary way for the formerly enslaved to ensure basic sustenance; however, as sites of food production, gardens also served as sites of deep cultural memory. Food is among the most intimate of all human social products. From its cultivation, through it circulation, to its consumption, food is an object by which communities reproduce fundamental cultural values and perpetuate valued practical knowledge. In this way, more than simply serving as a site from which to eat, garden plots reworked and recreated the semi-autonomous spaces that Black communities had built between plantations and farms into the shifting spatial patterns that sought to re-confine Black life to spaces of death in the city.

Recently-freed communities had to negotiate the very fringe of the landscape, often directly facing and precipitating its transformation with the imprints of the fleeting Black commons. Black communities continued their reciprocal uses of the landscape and waterways. Seeking to live without the basic guarantees of social protection or insurance, Black communities in the nation’s capital actively devolved the improvements made along the banks of the Potomac during the Civil War to create shelter in which they might survive. In the process, Black communities set off the return of vegetation to the edge of the Potomac. By 1892 Black communities in the cities Southwest section appropriated the Civil War–era forts for their wood, using it for fuel and the better parts for shelter. As one observer wrote, “nature has thrown over the signs of man’s preparation for mortal combat a mantle of grass and vines, shrubs and bushes, and if the sword has not been beaten into plowshare, at least the wood work of grimly menacing forts has been converted into firewood or the building material of negro chanties.”63 Black communities’ active devolution of the fort infrastructures in order to create shelter countered the vision of contemporaries who envisioned a more actively used Potomac and the increased growth of the District. One writer viewed the development of the Potomac waterway to full capacity as part of healthy future: “In the future Washington the Potomac River will be utilized to its full capacity for the benefit of the trade, health, and pleasure of the city.” Promoters of the city’s industrious and lucrative potential publicly expressed grievances about the kinds of impediments that a fugitive and outlaw world presented. The same author celebrated the disappearance of “a criminally infested mall” that alongside “high bluffs” and other features of the river edge had been “obstacles of the past” to “easy access to the river front.” Another writer lamented the devolving landscape at the Potomac’s edge as hindrances to the “health and commerce of the city” and described “the marshes which skirt the entire front of our city” as a result of “years of neglect of the commercial and sanitary interests of the nation’s capital.” Moreover, this writer viewed the “remedy” to the ills of the marshes as “a judicious plan of harbor improvements” and the “reclamation of the Potomac bottoms.”64

In contrast to the dominant vision that conflated economic development and infrastructural improvement with health and wellbeing, Black communities created the possibility for ruinate, or the partial return to bush, at the river’s edge. Black communities’ efforts at survival doubled, as those seeking mostly inadvertently to restore a natural barrier of vegetation to prevent the further deterioration of the banks and the silting of the waters. Black communities then also engaged in the work of ensuring a kind of Black commons upon which the urban Black population depended for some of its social currency in the form of fisheries. Although Black communities were marginal within discussions of the city’s future, their efforts here nevertheless index their ongoing contest over the nature of the future of the landscape and waterways of the Chesapeake. Their active devolution of the landscape contrasted sharply with the efforts of boosters and other urban futurists who viewed trade and real estate market growth as the basis for the city’s future.

Fishing continued to be a source of livelihood in the region in the decades following emancipation along the Potomac as the river provided what observers described as “a lucrative occupation to the numerous fishermen that inhabit its banks.”65 Drawn in by seine nets set for various species including a set of species known vernacularly as herring, these fish provided social and economic currency to post-emancipation communities who “chiefly disposed of [the catches] to fish peddlers, who visit periodically the little settlements of fishermen on the shore, and purchase supplies for their excursions into the interior.”66 Although undoubtedly the author was referring to various communities, Black and otherwise, fishing was particularly important to Black communities who endured limited opportunities for employment and enjoyment in the aftermath of the Civil War.

Fishing also illustrated the tenuous line Black communities navigated, between using the commons to create the possibilities for Black futures, and the further commercialization of the Commons. This conundrum illustrates the ongoing threat of the survivability of local fisheries within the Bay and its tributaries precipitated by commercialization. What Karl Marx understood as primitive accumulation, or a one-time round of expropriation that marked the rise of capitalism, Black communities registered this kind of enclosure and theft as cyclical and ongoing. Black communities staked a tenuous relationship between their perpetuation, cultivation, and preservation of the Black commons and the exploitation of their labor to overtax the fisheries of the Chesapeake.

No example better represents this conundrum than the evolving relationship between the region’s Black communities and oysters. For example, after formal emancipation, Black communities located independent employment in oyster fishing along the reeves in the Potomac and the Rappahannock, while Black women and children found work in shucking houses. This boon to Black economic life, however, intensified in its exploitation through the further marketization of the trade. As the Chesapeake became the world’s primary supplier of oysters, Black laborers were further taxed for profit and soon became the primary agents in the extinction of the Bay’s native oyster populations as a result of overharvesting. This was common among other fisheries as well, including American shad for which Congress passed a law in the early 20th century officially outlawing the fishing of shad within the District of Columbia in recognition of the dwindling fish population (Figure 1).

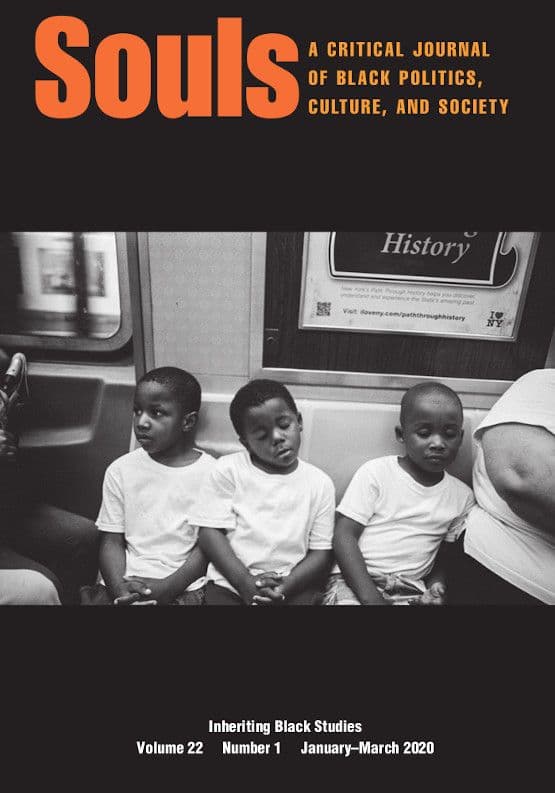

And yet, Black communities who continued small-scale recreational fishing maintained the impulse of the earlier uses of the Black commons well into the 20th century (Figure 2). Through line fishing alone or in groups, Black communities in Washington and in other rural and urban communities around the Chesapeake littoral continued to use the Potomac, Anacostia, and the various other creeks and rivers to procure food and to self-fashion through casual recreation (Figure 3). Small-scale and even lightly commercial forms of fishing continued as part of the vernacular infrastructure of the Black commons around the Chesapeake.

Figure 1 Bain News Service, publisher, Shad Fishing, ca. 1910 (between and ca. 1915). Photograph from Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, George Grantham Bain Collection, LC-DIGggbain-18897.

In the 20th century, Black communities continued the elements of the plot and to view and use aspects of the river as a fleeting commons even as they became increasingly detached from the land. This was part of the continued articulation of a different vision of social and cosmological integrity in urban Washington into the 20th century that white commentators interpreted as “quaint survivals.” In a 1909 article in the Washington Post, an unnamed author described the city’s Central Market as a “museum of American antiquities—not of the prehistoric sort—but antique in the American sense of the term: that is to say, from 80 to 100 years old.” In addition to the “curiosity” of an older man selling the Hagerstown Almanac, which indexed the maintenance of folk forms in the nation’s capital, the writer described a large fish stall where fishermen sold oysters, dried and smoked fish, and terrapin. According to the writer, the labor of drying and smoking alewives, known vernacularly as “herrings” on the Virginia and Maryland sides of the Potomac, was “done by negroes, the descendants of old slaves, who have transmitted the art of drying and smoking fish from one generation to another for two centuries.” Black communities continued to employ the commons to maintain social continuity and Black culture.

Figure 2 John Ferrell, photographer, Washington, DC vicinity, Negro fishing on the Virginia side of the Potomac River below the Chain Bridge, Arlington County, Virginia, July 1942. Photograph from Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, FSA/OWI Collection, LC-USF34-011585-D.

In addition to the market fish stalls, the writer also discovered “venerable Negro women with All the Healing Herbs” who developed “old-fashioned and forgotten remedies … for simple ills of simple people in a simple age.” The woman whom the author paternalistically names “Aunt Matilda” raised herbs including callamus root, sweet marjoram, thyme, sage, mullen, mint, and others in her “little garden at Anacostia.” According to the author, Aunt Matilda also gathered and sold bark and roots, including sassafras, May apple root, and Black walnut root that she gathered in the woods.” This account refers to these various products foraged from the forest and grown in a plot in Anacostia as remedies for ulcers, hair dye, swollenness, cramps, and other ills. Critically, Black communities and especially Black women and other post-emancipation “captive maternals” continued to look to the plot and the wider Black commons for elements of a fleeting social world despite the ongoing enclosure marked by urbanization. Black women in particular continued to forge a distinctive vision of ecology that remained opaque within a vision of Washington’s future that cast Black social life and Black ecological knowledge as “old-fashioned” and therefore no longer a viable form of knowledge or mode of living in the city. Black Virginians and Marylanders on both sides of the Potomac also continued to maintain their own nomenclatural practices outside the classificatory system of dominant science. As the author wrote, “some of the names she [Aunt Matilda] has for different herbs are decidedly curious and employed only by the old-time Virginia and Maryland negroes” including “Adam and Eve,” “a wild-growth” “eighty-five years ago … well known as yielding a very excellent and lasting glue or paste.” The writer sought to render these alternative uses of the resources of the commons and the plot to “old plantation remedies” and thus to a bygone era, collapsing Blackness and Black life to “antiquity.”

Figure 3 Toni Frissell, photographer, African American woman, seated on ground, fishing, at the Tidal Basin, Washington, DC, September 1957. Photograph from Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Toni Frissell Collection, LC-DIG-ppmsca-01947.

Yet, for me this is further evidence of the power and possibilities of how Black communities continued alternative uses of the land and water. Black communities maintained a vision of social–cosmological–ecological integrity at odds with the dominant vision of mastery and commodification. These communities envisioned and practiced fleetingly the Black commons through spaces in which their actions were hidden or opaque to outsiders. These practices were at odds with the forced extraction of their labor by slave owners and later employers and helped cultivate and perpetuate Black holes or illegible spaces in which they could continue to practice their visions for social–cosmological–ecological integrity outside of mastery and dominion. The plot and the wider Black commons remain as usable histories of alternative land and water resource allocation as we must confront the possibility of the lower Chesapeake’s ongoing overdevelopment and toxification.

Critically, the history whereby enslaved and post-emancipation communities plotted the Black commons diverges other histories of environmental consciousness. While mainstream environmentalism most often maintains the Man–subject–earth–object relations of mastery implied even in “saving” this or that species or ecosystem, revealing its indebtedness to the history of conservation developed to enhance rather than displace exploitation, Black ecologies emerging from the Black commons suggest the power of reciprocal social relations between people as a praxis capable of sustaining human relations and the biosphere. If for Marx the commons was the “people’s land” prior to enclosure, then Black qualifies the traditional consideration of the commons by examining the strain Blackness has placed on notions of “the people.” As communities born of a kind of orphanage, natal alienation, and social estrangement, enslaved and post-emancipation Black communities retained a generative and queer form of anthropocentricity that focused primarily on the extension of new modes of human connection, belonging, and reciprocity.67 These registered in excess of the logics of markets and normative social reproduction and extended a different vision of earth stewardship. These visions for belonging otherwise queried the normative operations of property and “Man,” which are at the heart of our confluence of ongoing social and ecological catastrophe, the so-called Anthropocene or the racial capitalocene.68 Through the alternate vision of the Black commons, Black communities in the lower Chesapeake engendered thriving in places where nothing was said to exist, and in that unnaming, where nothing is expected to live, except in its barest forms.69

Acknowledgments

I thank Tikia Hamilton, Sarah Haley, Jaz Riley, Alex Alston, Ellen Louis, and Julius Fleming for helpful engagement with various iterations of this article. As well, I thank Jarvis McInnis and Justin Hosbey for their ongoing engagements with me regarding Black ecologies. As always, appreciation to Huewayne Watson.

This article extends an argument I initially made in a digital piece, “Towards a Usable History of the Black Commons,” Black Perspectives (February 2017), https://www.aaihs.org/towardsusablehistories-of-the-black-commons/ (accessed February 28, 2017).

WORKS CITED

1. Here in describing the river as an ecotone, I follow Joshua Clover and Juliana Spahr who describe an ecotone as “the meeting point of two ecologies across which value flows.” “Gender Abolition and Ecotone War,” South Atlantic Quarterly 115, no. 2 (April 2016): 291–311. Here various kinds of value are created at the meeting of the river and the city’s human communities.

2. Brady Dennis, “Trump Budget Seeks 23 Percent Cut at EPA, Eliminating Dozens of Programs,” The Washington Post, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/energyenvironment/wp/2018/02/12/trump-budget-seeks-23-percent-cut-at-epa-would-eliminate-dozens of-programs/?noredirect¼on&utm_term¼.2d120a0c8c2e (accessed February 6, 2018).

3. According to a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association report from 2012, approximately 17,000 people, primarily African American, Latino, and Asian regularly consume catfish from the Anacostia River. https://response.restoration.noaa.gov/ about/media/study-reveals-dc-community-near-anacostia-river-are-eating-and-sharing contaminated-fish (accessed January 8, 2017).

4. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, “Tumors in Catfish from the Anacostia River, Washington, DC,” Report of the Chesapeake Bay Field Office, undated, https://www.anacostiaws.org/ userfiles/file/BullheadFS.pdf (accessed November 1, 2016). For a study of the toxic effects of polynuclear aromatic compounds in other rivers on the Chesapeake see Alfred Pinkney et al., “Tumor Prevalence and Biomarkers of Genotoxicity in Brown Bullhead (Ameiurus nebulosus) in Chesapeake Bay Tributaries,” Science of the Total Environment 410 (2011): 248–57. This species is a species introduced for food and sport in the late 19th century.

5. Chris Myers Asch and George Derick Musgrove, Chocolate City: A History of Race and Democracy in the Nation’s Capital (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017).

6. Take the example of the Anacostia watershed, which between 1970 and 2000 lost 70% of its forested area. Impervious surfaces now cover 25% or more of the watershed.

7. On dominion and biblical justification see Delores S. Williams, “Sin, Nature, and Black Women’s Bodies,” Ecofeminism and the Sacred, ed.Carol J. Adams (New York: Continuum, 1993): 24–29 and Wende Marshall, “Tasting Earth: Healing, Resistance Knowledge, and the Challenge to Dominion,” Anthropology and Humanism 37, no. 1: 84–99.

8. Timothy Silver, A New Face in the Countryside: Indians, Colonists, and Slaves in South Atlantic Forests, 1500–1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990); T. H. Breen, Tobacco Culture: The Mentality of the Great Tidewater Planters on the Eve of the Revolution (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2001); Edgar T. Thompson, The Plantation (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2010 [1935]).

9. J. B. Jackson, “The Virginia Heritage: Fencing, Farming, and Cattle Raising,” Landscape in Sight: Looking at America, ed. Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1997): 129–38.

10. Jack P. Greene, ed., The Diary of Colonel Landon Carter of Sabine Hall, 1752–1778 (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1965): 127–200.

11. I borrow the language of hybridity from Brian McCammack, Landscapes of Hope: Nature and the Great Migration in Chicago (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2017).

12. J. Kameron Carter and Sarah Jane Cervenak, “The Black Outdoors: Humanities Futures After Property and Possession,” Humanities Futures Blog of the Franklin Humanities Institute, https://humanitiesfutures.org/papers/the-black-outdoors-humanities-futures-after property-and-possession/ (accessed August 1, 2018).

13. Joy James, “The Womb of Western Theory: Trauma, Time Theft, and the Captive Maternal,” Carceral Notebooks, vol. 12 (2015), http://www.thecarceral.org/journal-vol12. html (accessed October 30, 2018).

14. Sylvia Wynter, “Novel and History, Plot and Plantation,” Savacou 5 (1971): 95–102. Thank you to Nijah Cunningham for introducing me to this essay.

15. Sonya Pomentier, Cultivation and Catasrophe: The Lyrical Ecology of Modern Black Literature (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2017), 41.

16. Lynn Rainville, Hidden History: African American Cemeteries in Central Virginia (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2014).

17. Cedric J. Robinson, Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition, 2nd ed. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000).

18. Karla F.C. Holloway, Passed On: African American Mourning Stories, A Memorial (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003), 2.

19. Sharon Patricia Holland, Raising the Dead: Readings of Death and (Black) Subjectivity (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2000), 15.

20. Vincent Brown, The Reapers Garden: Death and Power in the World of Atlantic Slavery (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008), 152; 7.

21. Dagmawi Woubshet, The Calendar of Loss: Race, Sexuality, and Mourning in the Early Era of AIDS (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2015), 3. See as well for further reflection on the way that proximity to death reorients Black life, Darius Bost’s forthcoming, Evidence of Being: The Black Gay Cultural Renaissance and the Politics of Violence (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, forthcoming).

22. H. R. McIlwaine and Wilmer L. Hall, eds., Executive Journals of the Council of Colonial Virginia (Richmond, VA, 1925–1945), I: 86–87. Also in Warren M. Billings, The Old Dominion in the Seventeenth Century: A Documentary History of Virginia, 1609–1689 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1975), 160.

23. Nicholas May, “Holy Rebellion: Religious Assembly Laws in Antebellum South Carolina and Virginia,” American Journal of Legal History 49, no. 3 (2009): 237–56.

24. Eugene D. Genovese, Roll, Jordan, Roll: The World the Slaves Made (New York: Vintage, 1976); Albert Raboteau, Slave Religion: The “Invisible Institution” in the Antebellum South (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1978). As Browne notes, in 1722 the Common Council of New York City regulated burials to no more than twelve attendees plus pallbearers and gravediggers in order to cut down on possible conspiracy. Simone Browne, Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015), 78.

25. Lynn Rainville, Hidden History: African American Cemeteries in Central Virginia (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2014).

26. Barbara Heath, “Space and Place within Plantation Quarters in Virginia, 1700–1825,” Cabin, Quarter, Plantation: Architecture and Landscapes of North American Slavery, ed. Clifton Ellis and Rebecca Ginsburg (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2010), 156–76.

27. Katherine McKittrick, Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006), 37–64.

28. Rebecca Ginsberg, “Escaping Through a Black Landscape,” Cabin, Quarter, Plantation: Architecture and Landscapes of North American Slavery (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2010), 54; Stephanie M. H. Camp, Closer to Freedom: Enslaved Women and Everyday Resistance in the Plantation South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004); Dell Upton, “White and Black Landscapes in Eighteenth-Century Virginia,” Places, 2, no. 2 (1982): 95–119.

29. Federal Writers’ Project: Slave Narrative Project, Vol. 8, Maryland, Brooks-Williams. 1936. Manuscript/Mixed Material. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/ item/mesn080/ (accessed January 12, 2017).