VOL. 20

The Aesthetic Insurgency of Sandra Bland’s Afterlife

Phillip Luke Sinitiere

ABSTRACT

DOWNLOAD

SHARE

I too have been bitten by the bark/of a white man’s voice.

—Simone John, “On [Not] Watching the Video”1

Eventually, all black people die. I believe when a person dies the black lives on.

—Danez Smith, “Short Film”2

Make mine the body of a 28-year-old black woman in a blue patterned maxi dress cruising through Hell on Earth, TX again alive.

—Marcus Wicker, “Conjecture on the Stained-Glass Image of White Christ at Ebenezer Baptist Church”3

In November 2015, student actors from Prairie View A & M University’s (PVAMU) all-black theater troupe, the Charles Gilpin Players, staged a fifteen-minute performance in honor of Sandra Bland in front of Waller County Jail where Bland had died four months prior. The performance opened with the lead actor singing “Wade in the Water” followed by actors mimicking death in the form of a “die-in” protest as they dropped on the jail’s front steps while saying the names of recently departed black people (e.g., Sandra Bland, Trayvon Martin, Yvette Smith, Prince Jones Jr.). Between songs by the lead actor—she sang parts of “Amazing Grace,” “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” and “Take My Hand, Precious Lord”—actors came back to life in a figural resurrection to reclaim the deceased’s character and reputation.4

About eight-and-a-half minutes into the play, Sandra Bland comes alive and the actor recites a portion of Bland’s April 8, 2015, “Sandy Speaks” video in which she critiques the “All Lives Matter” retort to “Black Lives Matter.”5 In the play, Bland begins with her characteristic “Good afternoon my beautiful kings and queens,” waxes eloquent about structural racism, and calls out the illegitimacy of colorblindness. “I need everyone to realize,” she says, “that Black Lives Matter.” Rehearsing the events that transpired during her traffic stop, the actor repeats Brian Encinia’s request to “put out your cigarette” and his threat, “I will light you up!” The Bland actor concluded: “I was thrown into a jail cell and what happened three days later: I was found dead by supposedly wrapping a plastic noose around my neck. July 13, 2015, and look at me now, Sandra Bland.”6

The remainder of the Gilpin Players’ performance features the lead actor’s powerful monologue about “black privilege” followed by several call-and-responses expressed at times through heavy breathing, a sonic inflection calling to mind Eric Garner’s death. “Black privilege is the hung elephant swinging in the room. Black privilege is the memory of a slave ship, waiting for Alzheimer’s to kick in. Black privilege is pretending,” she says, that black people are safe from death. “It’s tiring, you know, for everything about my skin to be a metaphor, for everything black to be pun intended, to be death intended. Black privilege is the applause at the end of this poem.” “Speak to the heavens for freedom,” she continues, “speak to that pain so that change may come. Speak to the younger generations, speak my people! Act my people!” With the troupe’s black fists raised, in unison they proclaim, “Preach, black lives matter!” The play ends with the troupe literally lifting the Sandra Bland actor on their shoulders as they depart Waller County Jail’s front steps singing “Take My Hand, Precious Lord.”7

The Gilpin Players performance serves as a powerful point of departure to examine and analyze the aesthetic insurgency that Bland’s death provoked and inspired. In the short time since her death, scholars have addressed the case of Sandra Bland through the subjects of law, discourse analysis, feminism, media studies, philosophy, and religion.8 This article combines historical and cultural analysis to observe how theater, music, poetry, and visual art serve as platforms to stage resistance to police violence against black women. It argues that aesthetic insurgency and cultivation of the imagination are vital components in the types of work necessary to instigate social change, by which I mean efforts towards societal repair that recognize black people as human beings. Such societal reconfiguration is no small matter given the white supremacist, anti-black legal, economic, and social scaffolding upon which the United States is built. When I speak of social change I am not talking merely about representational politics; I mean to emphasize shifts, changes, and adjustments in social, cultural, and economic power—an adjustment in material relations—through newfound and collective expression of freedom in both individual and communal dimensions expressed especially through the arts.9

This article’s use of the phrase “aesthetic insurgency” refers to creative expressions that respond directly to forms of political, social, and economic injustice. Poetry and visual art are the creative expressions with which this article is most concerned.10 “Insurgency” evokes the black radical tradition and its modes of thought. It recognizes the dialectic between white supremacy’s legal, economic, and social arrangements and active resistance in support of economic equality, political liberation, personal dignity, and unapologetic pride in blackness as personhood. The work of historian Robin D. G. Kelley informs both my understanding and articulation of black radicalism and art. I view artistic creations as expressions of “freedom dreams” to probe how artists’ work envisions and enacts liberation and emancipation. Kelley forges praxis with imagination to mobilize the mental and existential transformation needed to alter material, political, and social realities for black people in everyday life. “It is about how people in transformative social movements, moved/shifted their ideas, rethought inherited categories,” he writes, and “tried to locate and overturn blatant, subtle, and invisible modes of domination.”11

Utilizing art forms to stage narrative demands of black self-determination has deep historical precedent both in Texas and throughout the nation, especially since the Charles Gilpin Players started at Prairie View State College in 1929.12 The PVAMU troupe’s beautifully subversive performance marked Waller County Jail as a site of death while it simultaneously reenacted life—Sandra Bland’s afterlife to be more precise—on the front steps of a carceral institution. Re-staging historical events, the play contextualized Bland’s life and death in relation to state violence against black people, specifically police violence against black women.13 The Gilpin troupe’s “freedom dreams” through the social performance of theater actualized Bland’s life in the face of death. Re-enacting a “Sandy Speaks” video rescripted Bland’s words and staged an expression of her afterlife that called for collective justice for black bodies targeted by the state’s legal and law enforcement crosshairs. Relatedly, to invoke Kelley again, justice-oriented aesthetic creations are articulations of what he means by “freedom dreams.” Transgressive, insurgent social movements physically and materially express the incubation of black radical imaginations.14

The contemporary work of the Gilpin troupe exists in longitudinal conversation with the current epoch of Black Lives Matter (BLM), the Movement for Black Lives (M4BL), and #SayHerName. Despite having different objectives, aims, histories, and strategies, there is a consonance between these groups and coalitions: black people are human beings, and not random, expendable appendages to the current age of late capitalism. BLM activism is not the only consequential kind of “social performance” activism in contemporary times.15 The political and cultural logic of the #SayHerName movement supports similar kinds of activist and artistic resistance to state violence. Activist-intellectuals like Kimberl,e Crenshaw, under the auspices of the African American Policy Forum, lifts up and proclaims the name of black women in particular through narrative publications, quantitative study, and art.16

Aesthetic Insurgency and Slavery’s Afterlife: The Past in the Present

Linking the aesthetic insurgency of freedom dreams to what I call Sandra Bland’s afterlife draws on the black feminist thought of Christina Sharpe. Her conceptualization of “the wake” illuminates slavery’s afterlife and how we might read, view, hear, or otherwise experience aesthetic articulations about Sandra Bland (e.g., poems, music). In the broadest view, Sharpe’s In the Wake: On Blackness and Being considers the idea of the wake as consequence; that is, the wake is a theory of outcomes. But grasping outcomes, what I term history in the present tense—a version of what Saidiya Hartman refers to as “slavery’s afterlife”—is not to sit at a terminus or end. The wake seeks to trace out from the past sequential movements of time that culminates in outcomes, while it simultaneously imagines and reimagines what exceeds or might extend beyond an outcome. It is at once a refusal of expectations and “an insistence on existing: we insist Black being into the wake.”17 Sharpe draws from several definitions of wake: the lined waves that follow a ship’s parting of water, or a swimmer’s movement in a pool; the currents that follow an object’s movement through the air; the act of vigil-keeping for the deceased; communal rituals of remembering the dead in affective registers of sadness or celebratory joy; or intellectual or cultural registers of memory-making or memory-keeping.18 Yet the wake is not merely a theory of outcomes, and it is certainly not benign: it signals death and the incessant, crawling traumas that constitute the consequence of the nonbeing of blackness in western culture’s history. However, white supremacy’s wiliness, its shrewd, sadistic ability to reinvent and repurpose more prevalent oppressions paradoxically signals the resolute presence and absolute being of blackness despite extraordinary duress. “I am interested in plotting, mapping, and collecting the archives of the everyday of Black immanent and imminent death,” Sharpe writes. She’s also interested in “tracking the ways we resist, rupture, and disrupt that immanence and imminence aesthetically and materially.”19

Documenting disruptions and chronicling the everyday quotidian expressions of refusal and survival, of simply being, is what Sharpe describes as living in the wake or doing “wake” work. She describes the wake’s paradoxical presence: “to be in the wake is to occupy and to be occupied by the continuous and changing present of slavery’s as yet unresolved unfolding.”20 Recognizing the presence of the wake is not just an act of mental acuity or an intellectual exercise, it is “a form of consciousness.”21 Wake work, then, manifests such consciousness in the form of material or aesthetic creations, literary or artistic provocations that name black being—in other words the “orthography of the wake.”22 The textual or visual expression of black being materializes wake work’s presence, its ethics of recognition. Its praxis announces the possibilities that aesthetic invention holds in marking both totalizing captivity and freedom’s enfleshment. “If we are lucky,” Sharpe exclaims, “the knowledge of this possibility avails us particular ways of re/seeing, re/inhabiting, and re/imagining the world. And we might use these ways of being in the wake in our responses to terror and the varied and various ways that our Black lives are lived under occupation.”23

Thinking with Hartman’s conceptualization of slavery’s afterlife and Sharpe’s theoretical framework of the wake, I want to consider in the balance of this article the historical and cultural work of poetry and visual art as both a mode of documentation and simultaneously a method of resistance. In what follows I demonstrate how poems and visual images associated with Sandra Bland capture society’s (that is, anti-blackness’s) fixation and obsession with the elimination of black being while at the same time their very aesthetic performance elicits a dynamic and defiant refusal of containment, of subjection to silence. Posed interrogatively: how might the aesthetic insurgency around Sandra Bland’s afterlife simultaneously mark and name the insidious apparatus that led to her death and unapologetically declare and display the very fibers of her black being in the wake?24

Sandra Bland Protest Poetry

Forty-nine minutes, eleven seconds. That is the length of the dash-cam video footage of Sandra Bland’s traffic stop that the Texas Department of Public Safety released on July 21, 2015.25 Brian Encinia first speaks to Sandra Bland at the 2:41 mark (“Hello ma’am. We’re the Texas Highway Patrol and the reason for your stop is because you failed to signal the lane change.”), and after 15:45 we no longer hear Bland’s voice because she is in the back of Prairie View officer Penny Goodie’s patrol car awaiting transport to Waller County Jail.26 This stunning digital record of Sandra Bland’s arrest on July 10, 2015—more specifically the thirteen-minute encounter between her and Encinia that captured the perpetration of his verbal and physical violence—is the primary visual archive around which written and spoken word poets and musicians perform aesthetic insurgency. Drawing from Hartman, I call this Sandra Bland’s “scene of subjection.”27

White literary scholar James McCorkle’s poem “Light You Up” zeroes in specifically on the video’s verbal and physical climax: Encinia’s bombastic threat followed by Bland’s forced removal from her car, an abduction. “Though he did not technically kill her,” McCorkle’s narrative poem reads, “he sentenced her to death, what he said sent her to Waller County jail, where she was executed.”28 The title’s metaphorical meaning prefigures violence, often in association with fire, which is to say the destructive power of heat where it is a military weapon (“bombing sorties”), or “it is said before something, or someone, is set afire and burnt.”29 McCorkle’s list of names that follows the word “burnt,” which include Sam Hose and Jesse Washington, makes the historical connection explicit: Sandra Bland’s death is like a modern lynching. “What are the dreams of arsonists when the body is to be the fuel?” he queries. “What is left to burn? To burn with hate—to arson the bodies of others is to burn is to lay waste to destroy.”30 The fires of death also symbolize white supremacy’s obsession with the control of black bodies; acts of oppression centuries old (“These are the names. Only a few of the names. Each connect to other names, so many these pages would go dark.”) manifest a divide between the powerful and the powerless, between the occupied and the settler. Rhetorically he wonders how many other Sandra Blands he passed on the highway or the roads on which he observed black motorists pulled over by police officers. McCorkle thus names his white privilege in the poem; his own subjectivity produces a kind of ordinariness of how flippantly white Americans fail to see black subjects, or black suffering, or black injustice; of how immoral and unethical silence is. “We have the clearance, the documents, the assurance to pass, to drive by to be on our way. To leave behind.”31 In this ordinary way, white supremacy’s “clearance” passes the burden of survival away from and off of white bodies, an existential pathway McCorkle’s poem lets linger disquietingly.

While McCorkle’s verse engages white subjectivity and white complicity in black death, writer Tiana Clark’s poem “Sandy Speaks” names the fear that McCorkle’s white body has the privilege to ignore. As a black woman she personalizes Bland’s story when she “check[s] the speed limit” and “push[es] the needle to cover just under 30 mph” to avoid potentially brusque encounters with police.32 “I click the turn signal in my car,” Clark writes, and “say her name.”33 To achieve a kind of equilibrium—the title of her book—Clark registers Bland’s voice to resist fear:

Sandy speaks to me beyond the grave

her voice on YouTube—

ricochets.34

A sound that ricochets is a sound that darts here and there, back and forth; it echoes, and it persists. Sandy’s voice abides on YouTube’s digital modality; pressing refresh reenters Bland’s life into the picture, thus she “testifies in Death.” Even though “The body is gone,” Clark maintains, “the words remain.”35

The digital discourse to which Clark’s poem refers finds textual life in black poet Simone John’s book Testify. “Testify” is a legal term; it is an act that serves to legitimize. The voice of testimony vouches for, or bears witness to. It aims to establish incontrovertibility, to seal proof about something. In Christianity, a testimony materializes divine activity; it sanctions spiritual meaning for an observable event. John deploys these modes of testifying throughout her book.

The third section of Testify, “Collateral,” transforms the transcript of Bland’s traffic stop into poetry. It strings together Encinia’s rhetorical viscosity with Bland’s taser-like responses to his verbal assaults. It is a concretized re-view of the dash-cam video’s visual power. “Sandra’s words live here without/the cushion of quotation marks,” writes John in “Ars Poetica.” “No asterisks. No caveats. No need./Black rage cannot be reworded.” In a religious register, John describes her poems as “a form of prayer” and “psalms/for slaughtered women.”36

“Enciting Incident: What’s Wrong” captures the opening moments of the traffic stop, and “Cigarette” letters one of the moments in the video where Encinia provoked, rather than de-escalated the situation, by asking Bland to put out her cigarette. “Lawful Order: An Abbreviated List” follows the moment after “Cigarette” when Encinia yelled for Bland to get out of her car, and then screamed, “I will light you up!” “Unanswered Questions” takes the reader to the moments immediately after Encinia handcuffed Bland and slammed her head into the ground, when she demanded to know the reason for her arrest, a rationale for her apprehension.37

“Lawful Orders: Aftermath” and “A Woman’s Perspective” continues the conversation that “Unanswered Questions” surfaces. The textual repository of these latter three poems increases the pressure building in “Collateral.” Encinia blamed Bland for her situation in “Lawful Orders” when he says “You started creating problems” and “If you would stop resisting.”38 “A Woman’s Perspective” presents a textual echo when an unnamed Prairie View police officer states, “Stop resisting ma’am./You should not be fighting.” In this same poem the Prairie View police officer—in direct collusion with Encinia—utters the dash-cam video’s first lie, “I saw everything.”39 Here Penny Goodie vouches for Encinia’s abuse, and justifies the apprehension; in retrospect, her testimony contributed to Bland’s death. The final poem in the Bland suite, “I Tried,” textualizes the closing minutes of the video when Encinia radios his superior to report the traffic stop. He described the encounter with Bland as “a little bit of an incident” in which he depicts her as a “flailing” black woman who was out of control, who “twisted away from me” when handcuffed. “Why they act like that, I don’t know.” Encinia describes the moment in which he threatens Bland with a Taser gun as unfortunate (“I mean I tried to put the Taser away”). Indirectly corroborating Goode’s testimony, that is, vouching for a fellow officer and verbalizing the thin blue line, Encinia compounds untruth by claiming three times that “I tried to de-escalate her.”40

The poems with which John intersects the Bland suite include four iterations of “Elegy for Dead Black Women,” as well as poems about murdered transgender women and the women whose lives Dylann Roof ended in 2015 at the Mother Emanuel AME (African Methodist Episcopal) church in South Carolina. “Elegy for Dead Black Women #1” calls forth the meaning behind Testify: “The first death comes by/bullet. The second, when they’ve/forgotten your name.”41 “On [Not] Watching the Video” and “For Colored Girls Who Have Been Asked ‘What’s Wrong’” grapples with internalized fear and rage that crackles below the skin’s surface during encounters with law enforcement, while “Murder” spools out the conclusion, the double-meaning of police violence at a traffic stop. In “The Poet’s Eulogy,” John unsettlingly imagines her own funeral at Concord Baptist Church in Roxbury, Massachusetts. “Simone did so much so young,” the minister preaches, “Like she knew the clock’s hands weren’t ticking in her favor.” After invoking the words of Jesus Christ about having a trouble-free heart in the midst of mourning—a biblical sense of testimony—the poem ends with prayer, with the imperative to “speak her name aloud.”42

Spoken word poets speak Bland’s name aloud. Black New Orleans–based artist FreeQuency delivered a powerful oration in 2015 at the Poetry Slam, Inc. finals titled “Say Her Name.” This poem figuratively resurrects Bland from the grave; she arrives to ask why black people continue to die at the hands of police, but more specifically, why the state continues to murder black women, many of whose names do not become hashtags. Like McCorkle’s use of lynching history, FreeQuency alludes to Eric Garner’s 2014 death in New York City as a lynching (“last year they told me a man in Staten Island killed himself with a noose made of police officers’ arms”). She critiques the attempted character assassination in which Waller County officials engaged by suggesting Bland smuggled weed into the jail (“they said … I got so high that I mistook myself for a ceiling fan, fixed myself back into place”), and then narrates the despair of isolation in carceral environments. In other words, jail officials discovered Bland dead “in the same square shaped casket they found Kalief Browder’s body in.” Like John’s “The Poet’s Eulogy,” FreeQuency addresses the place of collective mourning and meaning-making in African American culture. Speaking of Bland’s mother Geneva Reed-Veal, she states: “somehow in my death she was given a megaphone mouth to mourn with.”43

Similar to FreeQuency’s reference to the emotional labor of incarceration doubled up with systemic oppression, racism, and injustice, at a 2016 collegiate slam finals event at the University of Texas at Austin, African American poets Kai Davis, Nayo Jones, and Jasmine Combs forcefully addressed mental health in a piece titled “Sandra Bland.” They name her death as a lynching due to the collective pressures of white supremacy’s long life and oppression’s suffocating weight. “Oppression can kill you from the inside out,” they say. “We marched for a name, and neglected the woman.” About Bland’s death, police “called it suicide,” black people “called it murder.” But, they ask, “what if it was both?” They speak to the reality of trauma “stretching across generations” that leads to “crying for centuries.” What if Bland experienced internalized oppression that was “the culmination of all of our past lives caving in on her?,” they imagine, and her alleged suicide a “ceasefire,” a “final act of protest” against a society steeped in structural intentions to eliminate black people?44

The above poems construct the dash-cam video of the Waller County traffic stop that instigated it as an artifact of slavery’s afterlife. They address Bland’s scene of subjection from many different angles, and they unflinchingly name the police violence that led to her demise: McCorkle refers to Bland’s “execution,” Clark calls it “murder,” John deems her death “slaughter.” Moreover, McCorkle and John enact wake work through their poetic documentation of Bland’s life in the context of historical and contemporary violence against other black subjects. Collectively, their art—their freedom dreams—viscerally disturbs the waters of her memory.

Sandra Bland and Aesthetic Insurgency’s Visual Culture

Visual culture has long played a formative role in struggles for black freedom. During the 1800s, Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth used the power of photography for purposes of civil rights, and during the 20th century emerging technologies of radio, and later television, introduced new tools in the fight for liberation. Similarly, visual art harnessed imaginative expressions in the interest of societal transformation. Social media in contemporary times serves liberation struggles. After viewing photographs of the Ferguson rebellions in 2014, civil rights–era photographer Danny Lyon commented on the enduring power and possibility of visual images in freedom struggles.45 However, as Simone Browne documents, emerging technology, and wider networks of textual and visual connectivity create new tools for surveillance and state repression.46

In the words of art history scholar Maurice Berger, the aesthetic insurgency of Sandra Bland’s afterlife powerfully mediates her “corporeal world” and those whose creative work offers imaginative rendering of her life and legacy.47 The role of social media in the present era thickens the meaning of art and the visual inspiration from which artists imagine their work. Uniquely, the “Sandy Speaks” videos Bland made between January and April of 2015 recognized the power of visual culture in social justice work. In her first video from January, she suggested instructing young people about how to survive an interaction with police officers; she also challenged law enforcement who watched her video to tune into community voices in the interest of effective communication and equitable justice. Building on the point about community–police relations and commenting on the potential of new media’s role in activism, she looked directly into the camera: “This thing that I’m holding in my hand, this telephone, this camera, it is quite powerful. Social media is powerful. We can do something with this. If we want change, we can really, truly make it happen.”48 The visual archive of Bland’s digital corporeality, as it were, retrospectively exists as a perpetual record of her afterlife from which artists can continually draw. As historian Tina M. Campt shows, beholding visually the optics of black life and death acts both as an archive and as a mode of insurgent refusal.49

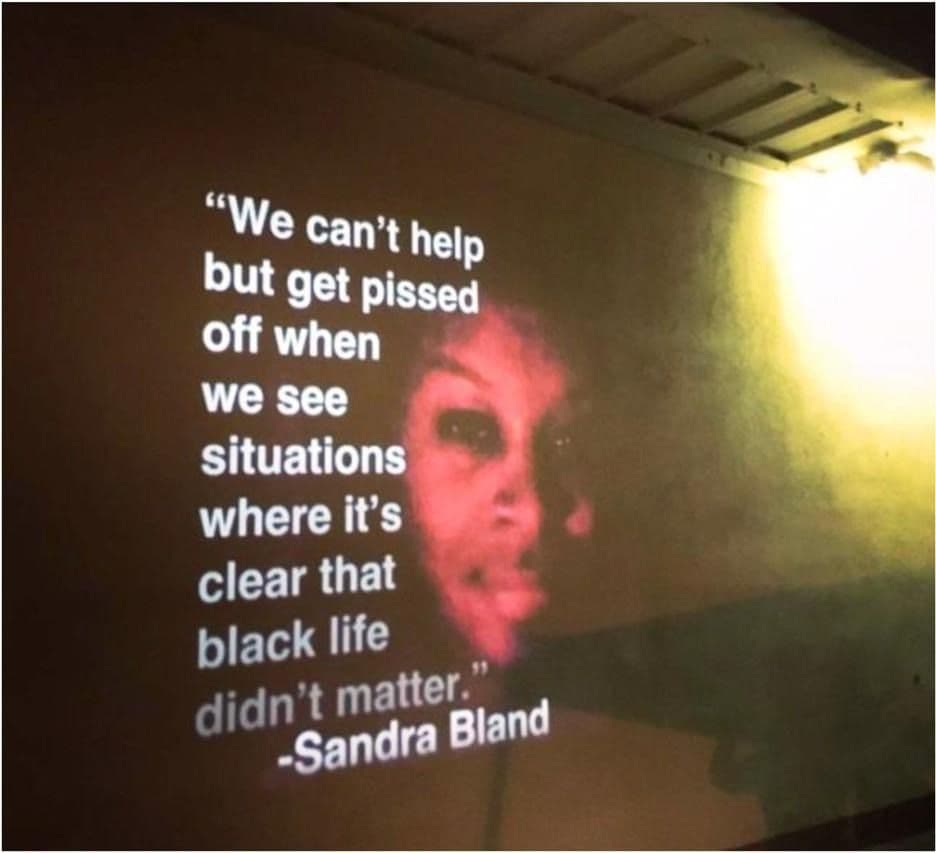

Figure 1 Sandra Bland image projected onto the wall of Waller County Jail, July 2016. Photo courtesy of Hannah Bonner.

A key example of digital, public art materialized about a year after Bland’s death. Activists in the Sandra Bland movement created a mobile instillation that was at once a political provocation and an insurgent, aesthetic intervention designed to mobilize cultural resistance to police violence against black women. In July 2016, to mark the one-year anniversary of Bland’s death, activists and artists, some of whom were Christian clergy, organized a 64-hour sit-in at Waller County Jail to commemorate her life and mark the amount of time she spent detained in a cell.50 The nonviolent direct action began with a “She Speaks” event at the site of Bland’s arrest just off the campus of PVAMU. Once it moved to the jail about five miles away, some of the activists commenced prayer walks around the facility, organized poetry circle readings, and conducted daily communion services in the jail’s parking lot—all under the watchful eye of Waller County sheriffs. In addition, during the day sit-in organizers played the audio of “Sandy Speaks” videos through an oversized speaker that faced the jail. Provocatively, Bland’s social justice–oriented videos literally spoke back to the institution in which she died. At night, activists powered up a projector and displayed images of Bland on the cream colored stucco walls of the jail while they played some of her videos. With the volume cranked up, for the full 64-hour protest her voice re-inhabited, even reentered the carceral space where she took her final breath. Aware of the power of visual politics, sit-in organizers circulated images online through Facebook and Instagram. This not only kept observers tuned in to the progress of the direct action, but also provided an opportunity to figuratively frame the aesthetic insurgency in which they were engaged. One Bland image posted on the jail’s wall included the text, “We can’t help but get pissed off when we see situations where it’s clear that black life didn’t matter,” commentary from a video dated April 8, 2015, in which she discussed the Black Lives Matter movement (Figure 1).51 The Instagram image’s caption commemorated her life and stated, “Her face. Her words. Her truth. Projected onto the walls that held her captive. You are free now Queen, and they all have to hear you.”52

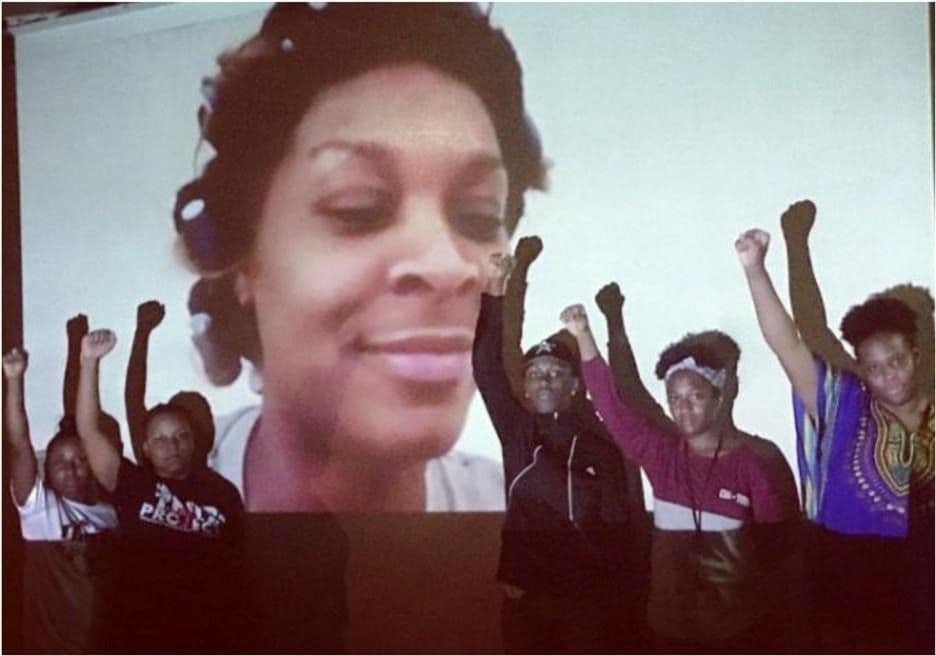

Figure 2 Sandra Bland’s image looks approvingly toward her sister comrades who participated in the 64hour sit-in, July 2016. Photo courtesy of Hannah Bonner.

Early on the final morning of the sit-in, organizers posted an image of Bland—a still from her very first “Sandy Speaks” video discussed above—whose smile casts an approving glance toward young black women activists (Figure 2). The black female fists rise in beautiful defiance and summon a provocative posture in support of a fallen sister comrade. They literally and figuratively stand against police violence on the property of the very institution in which Bland died.53

In early 2018 the Houston Museum of African American Culture (HMAAC) hosted an instillation called “Sandra Bland.” HMAAC Chief Executive Officer John Guess Jr., along with staff members and black artists such as Dominic Clay, curated the exhibit. A long-time advocate for multicultural art in Houston, Guess’s museum supports the work of local artists. He describes HMAAC as a place that creates “a multiracial, multicultural conversation on race.” It seeks to “bring empathy, healing, [and] understanding. … This museum is a museum for all people.”54 As a black artist, Guess had two aims for the Sandra Bland exhibit. First, to develop a deeper understanding of the fear that envelops African American encounters with law enforcement. And second, to signal to the Bland family that Houston cares about the tragic loss of their family member; that Houstonians still hear Sandy’s voice calling from beyond the grave; and that her memory remains inspirational for the pursuit of racial and economic justice.55

Figure 3 “Justice 4 Sandy” lapel pin that exhibit attendees received from Shante Needham, Sandra Bland’s sister. Author photo.

Bland’s mother Geneva Reed-Veal and Sandy’s sister Shante attended the opening in February 2018.56 With tears streaming down her cheeks, Shante handed each exhibit attendee a lapel button that read “Justice 4 Sandy” (Figure 3). Still stirred by her sister’s death, she maintains a vigilant posture of freedom work in the midst of grief. Far from being merely symbolic, Shante’s distribution of the lapel pin is a political act of demanding justice. Overall, the exhibit’s opening evening stirred artistic excitement coupled with the emotional, existential weight of death and memory, an aspect of what Sharpe calls “wake work.”

The Sandra Bland exhibit sat on HMAAC’s second floor (Figure 4). Rafters with an open ceiling hovered above the black-tiled display area. Large wall windows and a canopy window allowed natural light to inhabit the upstairs space. There were four distinct parts to the Sandra Bland exhibit: an expansive educational space coupled with three experiential “rooms” partitioned and sequenced according to different moments of the Bland story (Figure 5).

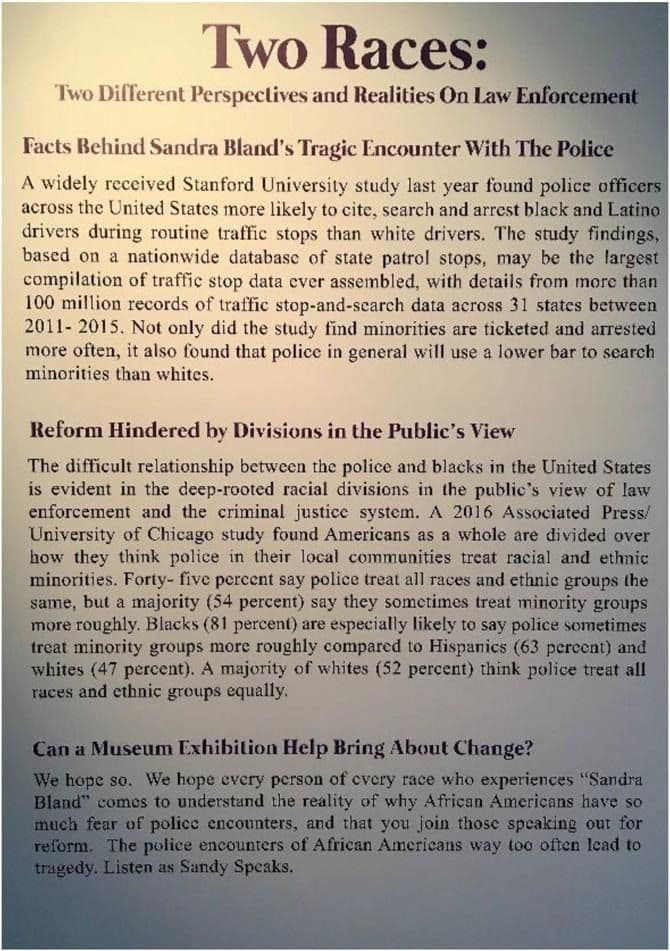

The large educational space included three wall plaques (Figure 6). One summarized Bland’s life, her educational and work history, and the Waller County arrest and detention that led to her death. Another plaque titled “The Talk” described how black parents prepare their children about how to survive encounters with the police even though they “acknowledge the heartbreaking reality that this does not guarantee their safety.” A final plaque, “Two Races: Two Different Perspectives and Realities On Law Enforcement,” cited university studies that document substantial distinctions in how white Americans and black Americans perceive police and police encounters (Figure 7). It ended on an educational point by suggesting viewers not only seek to understand divergent perspectives and why those opinions exist, but also mobilize efforts for social change. “Listen as Sandy Speaks,” the narrative concluded. In the middle of the plaques sat a big screen television on which looped clips from a New York Times op-doc, “A Conversation with My Black Son.” Directed by Geeta Gandbhir and Blair Foster, the film features interviews with parents about “the talk” as well as footage of them verbalizing a message to their sons, often through tears mingled with fear and love. Replicating a classroom, rows of chairs sat in front of the screen so that visually the plaques flanked the documentary television. This is the most specifically “educational” dimension of the exhibit: sonic and visual clues offered information about African American encounters with police.57

Figure 4 Entrance of Sandra Bland Exhibit. Author photo.

Figure 5 Panoramic view of the Sandra Bland exhibit. To the far left is the memorial space. Next is the dash cam room with the curtain to dim the setting; to the curtain’s right is a partition that makes the living room area of the exhibit. The handrail at the exhibit’s entrance is visible in the background. To the right is the television flanked by three wall plaques. The day I took this photo the chairs had not yet been set out and arranged. Author photo.

Figure 6 Educational space that replicates a classroom. The “Sandra Bland” plaque is to the left of the television, and “The Talk” is to the right. Author photo.

Three experiential spaces punctuated the Sandra Bland exhibit. The first space configured a domestic setting, which included a couch, end tables, and a chair that faced a television on which looped a video montage of Bland that played at her memorial service. Sandy’s church, Du Page African Methodist Episcopal Church, produced the video so there’s a distinct religious, even Christian, dimension to its contents. This was intentional on Guess’s part. “Greater understanding comes from some spiritual recognition of how you comprehend [Bland’s death],” he stated. “These are tragedies that have a spiritual element to them.”58 The “living room” invited museum attendees to “sit” with Bland. The memorial video included clips from “Sandy Speaks” vlogs. They featured Bland’s comments about her religious faith, and her desire to “racially unite” along with her intention to use camera and videos for activism “to change history.” Pictures of Bland and her family rested on the end tables. Thus, attendees met Bland in the first experiential sequence; they saw her smiling with family members and heard her voice on the “Sandy Speaks” vlogs.

Figure 7 “Two Races” plaque in the educational space of the exhibit. Author photo.

The second experiential space had a cardboard construction of a car’s front seats such that people see the dashboard. Looking through the car’s “windshield,” they watched a 10-minute segment from the dash-cam footage released by the Texas Department of Public Safety. Experientially, viewers felt the intensity, anxiety, fear, and anger of the Encinia–Bland encounter. The cardboard mockup has a Hyundai symbol on the steering wheel so viewers experience another layer when they figuratively sit inside of Bland’s Azera.

Figure 8 Memorial room of the Sandra Bland exhibit. Author photo.

The third experiential component of the exhibit replicated a chapel, a memorial space in which attendees sat as if attending Bland’s funeral (Figure 8). This space also invoked a wake. A small chest with shelves held candles and an ivy plant that symbolized living memory. A white cloth draped the wall behind the chest and on top of it, which invoked an African symbol of death. Two white votive candles accompanied a bowl of fruit, a bowl of water, another smaller flat candle, and an empty bottle. The bowl of fruit and water bowl symbolized life; an empty bottle signified that a libation had been poured for Bland. Copies of the memorial program awaited those who sat on one of three benches. This third partition of the experiential zone of the exhibit created a space of memory making and memory keeping, and a space in which to process having just witnessed the violent encounter between Encinia and Bland.

While Guess was familiar with Bland’s case due to Waller County’s proximity to Houston, his own brusque encounters with law enforcement animated his curatorial imagination. He conceived of the exhibit as a memorial, a testimony to who Bland was as a human being. Simultaneously, education was a central aim in his design. He wished to educate museumgoers about the fraught emotional, psychological, cultural, and historical space of black encounters with law enforcement. Furthermore, he wanted to document Sandra Bland’s life outside the dash-cam footage that often constitutes the sum total of her memory. He sought to create an exhibit in which museum goers might inhabit the space of fear that African Americans occupy when faced with law enforcement officers. But rather than let fear fester, Guess wanted the exhibit to foster intellectual growth that comes from being exposed to new information, data, or images. The museum space provided a place for healing for Bland’s family. Reed-Veal told Guess that the exhibit “allowed me to move out of a darker place … it allowed me to heal” just a little more while walking with grief. For Guess, Reed-Veal’s comment “underscores the success of adding a spiritual context to the exhibit.”59 To date, the exhibit has received requests to travel throughout Texas and even internationally. The interaction of local events with global currents of slavery’s afterlife reflects the ongoing artistic, aesthetic, and international dimensions of today’s black freedom struggles.

The Sandra Bland exhibit’s heartbeat, in concert with Guess’s overall vision for HMAAC, was educational. Its experiential pulse, as it were, aimed to deliver the fear that governs black–law enforcement relations while it acted to memorialize Bland in order to stir intellectual, social, or political responses. In so doing, the exhibit performed slavery’s afterlife by recognizing the psychological, emotional, and even physical landscape of black encounters with police. Yet simultaneously the place in which this performance of slavery’s afterlife happens—in a museum devoted to African American culture in Houston, roughly 70 miles from Waller County Jail where Bland died—aimed to use art insurgently as one way to attempt the possibility of healing and repair for a world in which white supremacy’s structural dehumanizing focuses on the categorical elimination of blackness.

The death of Sandra Bland, and the deaths of other black women who died in police custody, provoked the imagination of Houston artist Lee Carrier. As an African American woman, Carrier understands all too well the fear associated with police encounters. Yet, as an artist and educator, she possesses a valiant, practical sensibility that moves her to create art that instructs as much as it inspires. Carrier places education at the center of her aesthetic philosophy. As a classroom teacher and school district artistic director, she describes herself as a “practicing artist,” an artist-educator. She attributes such intellectual and artistic inspiration to Frida Kahlo, a radical, surrealist, and portraiture artist of Mexican descent; John Biggers, a black artist whose public instillations, quilt work, and distinctive use of patterns capture aspects of African American culture; Czech artist Alphonse Mucha, whose detailed art nouveau creations revealed exquisite detail; and the collaging practice of African American artist Romare Bearden. The dual identity Carrier possesses attunes her simultaneously to the pedagogical and creative dimensions of artistic innovation.60

For Carrier, these interests, influences, and perspectives converged the moment she received news of Bland’s death in 2015. She experienced sadness due to Bland’s death—along with grief about other contemporaneous deaths of black men and women at the hands of police—but also deep fear while driving. Survival and safety became (and remain) paramount concerns while on the road. Since the time of Bland’s death Carrier had a desire to create a mural about her in a communal environment, the kind of public art she often creates. That opportunity presented itself at HMAAC for the exhibit “Over There Some Place.” Designed for emerging artists of color from Houston and curated by local artist Dominic Clay, the exhibit focused on the African Diaspora from a southern vantage point. Clay brought together artists who worked in a variety of mediums and disciplines so that the exhibit would possess “cohesive yet ambiguous” qualities.61

Carrier’s Sandra Bland mural, Black in Texas, was part of a standalone wall on which her art is affixed (Figure 9). She attributed to “fate” the timing of her mural’s instillation simultaneously with the second floor Sandra Bland exhibit. Her preference for painting on plywood invested the art with a “natural” origin, after which she assembled paper bags as the mural’s material foundation. From there the use of wall papering and sketching out the painting’s centralized portrait start to give her piece a certain congruence and cohesion.62

Carrier described a range of emotions during the two-week process of painting Black in Texas. She had kept a close watch on Bland’s case for over two years, so the painting itself required no new research. However, a depth of sadness and occasional insomnia invested the experience because she had to return to images of Bland’s face in developing the portrait. “When I started working on the piece-… for a week it got to the point where information was so heavy it took a toll on me,” Carrier said. Painting Bland’s portrait became “spooky,” she continued. Troubled by the fact that “there’s these loopholes and there’s unanswered questions” about what Bland experienced in her final days and hours. “[I]t’s spooky,” she commented, “is really our justice system this corrupt? Can we really not trust police officers? Because we don’t know what happened … we only see footage of some violence that was committed against her, and then we don’t know anything else.” The act of painting Bland’s portrait and in some measure pushing through the process to the other side of completion brought Carrier deep satisfaction. Through the act and literal art of painting she symbolically worked through Bland’s death to a space that honored her life. Carrier’s art channeled Bland’s past to invoke her likeness in the present, thus staging it for and as it were into the future.63

Figure 9 Lee Carrier, Black in Texas, mixed media. Author photo.

Carrier described Bland’s pose as a “matter-of-fact woman” devoted to justice while embodying the truth of blackness and its beauty. She drew inspiration for Black in Texas from Alphonse Mucha’s 1911 Princess Hyacinth, which depicts a goddess whose leaning posture exudes control and confidence. In Carrier’s painting Bland exudes that same poise and gravity (Figure 10). Bland’s self presentation invokes the State of Liberty, Carrier explains, as if she’s holding a torch to light the way. Yet, wearing a broken crown symbolizes the disrepair which riddles the nation’s criminal justice system. The halo effect balances the painting even as it betokens to the imagination of the Christian symbolism of an afterlife in heaven. The blue and red patterns and shapes that reside above and behind the halo, and along the mural’s sides, reflects John Biggers’s influence. The gold with which Carrier adorned Bland, as well as the tribal art across her face, allude to the artist’s interest in indigenous cultures—specifically indigenous women—and draws in a transnational, diasporic dimension. In addition, the ruffled collar that sits around Bland’s neck symbolizes slavery’s afterlife: the practice of stifling, or silencing, black voices whether through the grotesque spectacle of lynching, or even the supposed reason of “asphyxiation” the state offered as the cause of Bland’s death. Opposite the ruffled collar, which again signals the artistic pattern of balance, sits a crown atop Bland’s head. The gold crown with blue jewels communicates the colors of Bland’s sorority (Sigma Ghama Rho), and identifies her as royalty, as a goddess deserving of veneration, respect, and commemoration.64

Figure 10 Close-up of Bland’s face, Black in Texas. Author photo.

Consonant with Carrier’s aesthetic philosophy the title Black in Texas is a play on words that evokes a cultural identity marked for a particular place. Alternatively, for Carrier the title stamps a public warning that black people might encounter racial hostility in Texas. In the mural, she imagined what Bland would look like today. In a conversation with Geneva Reed-Veal, Carrier commented that Bland’s mother spoke of the mural’s ability to prompt her arrival at a deep place of healing. “Your art brings healing and it is going to hold me for 6–8 months,” she revealed to Carrier. In the portrait, and on the mural board Bland rests in a pose that symbolizes strength in the search for justice. Thus, what Carrier described as the painting’s “gentle sense of urgency” acts insurgently to communicate the additional freedom work that remains in the case of Sandra Bland.65

Conclusion

Sandra Bland’s death, and the powerful dash-cam footage of her arrest and the verbal and physical violence she suffered at the hands of the police, is one of the signature events and iconic images of the era of BLM, M4BL, and #SayHerName. Starting in July 2015, Bland quickly featured in #SayHerName tweets and associated hashtags (e.g., #WhatHappenedtoSandraBland, #SandyStillSpeaks) across the spectrum of digital activism. Her case galvanized activists locally on the ground in Houston and throughout the nation. Protests against police brutality invoked her name through chants. Simultaneously, Bland’s life generated attention most specifically by the viral spread of her “Sandy Speaks” videos. Activists not only played her videos at protests as a way to literally bring her voice into spaces of resistance, but also used quotes from her videos on protest signs as a way to promote a communal connection and united front against police violence. As this article documents, Bland’s life and death stirred the imaginations of poets and visual artists. The social performance of their work named crimes, marked death, and recalled lives lost in calling for structural change. Combining black feminist thought with the creative capacity to proclaim humanity in a society built on and blanketed with anti-blackness demonstrates how aesthetic articulations of aesthetic insurgency bear historical and contemporary witness to Sandra Bland’s afterlife.

Acknowledgments

I thank Keisha Blain for the initial discussions that helped me to conceptualize this article. Gratitude goes to Charisse Burden-Stelly, Kali Gross, Olga Dugan, and Cynthia Gwynn Yaudes for helpful comments on earlier drafts. John Guess, Jr. and Dominic Clay of the Houston Museum of African American Culture deserve thanks for facilitating conversations about art and activism. I salute Houston artist Lee Carrier for sharing the story behind her art on Sandra Bland. Finally, I thank the Reverend Hannah Bonner for the use of Sandra Bland images.

WORKS CITED

1. Simone John, “On [Not] Watching the Video,” in Testify (Portland: Octopus Books, 2017), 57.

2. Danez Smith, “Short Film,” in Black Movie (Minneapolis: Exploding Pinecone Press, 2015), Kindle Version, Location 313 of 485.

3. Marcus Wicker, “Conjecture on the Stained-Glass Image of White Christ at Ebenezer Baptist Church,” in Silencer (Boston: Mariner Books, 2017), 3.

4. “The Charles Gilpin Players Perform in Honor of Sandra Bland,” Amplify the Shout (November 29, 2015), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v¼iB27hae87M8 (accessed April 1, 2016).

5. “Sandy Speaks—April 8, 2015 (Black Lives Matter),” https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v¼CIKeZgC8lQ4&index¼28&list¼PLMkogOT3Op_DO7CxQWwKU-BQEuN8sN3vW (accessed August 12, 2015).

6. “The Charles Gilpin Players Perform in Honor of Sandra Bland.”

7. Ibid.

8. Josh Bowers, “Annoy No Cop,” University of Virginia School of Law Public Law and Legal Theory Research Paper Series (March 2017): 1–74; Belen V. Lowrey-Kinberg and Grace Sullivan Buker, ““I’m Giving You a Lawful Order”: Dialogic Legitimacy in Sandra Bland’s Traffic Stop,” Law and Society Review 51, no. 2 (2017): 379–412; Ashley B. Reid, “The Sandra Bland Story: How Social Media Has Exposed the Harsh Reality of Police Brutality” (M.A. Thesis, Bowie State University, 2016); Brian Pitman, Asha M. Ralph, Jocelyn Camacho, and Elizabeth Monk-Turner, “Social Media Users’ Interpretations of the Sandra Bland Arrest Video,” Race and Justice (2017): 1–19; Victoria D. Gillon, “The Killing of an ‘Angry Black Woman’: Sandra Bland and the Politics of Respectability” (Winning Paper, Eddy Mabry Diversity Award, Augustana College, Augustana Digital Commons, 2016), https://digitalcommons.augustana.edu/mabryaward/3/ (accessed August 12, 2017); Andrea J. Ritchie, Invisible No More: Police Violence against Black Women and Women of Color (Boston: Beacon Press, 2017), 101, 220; Theresa M. Senft, “Skin of the Selfie” (Unabridged Version, 2015), 1–21, http://www.academia.edu/15941920/The_Skin_of_the_Selfie_ Unabridged_Version (accessed August 12, 2017). An abridged version of Senft’s paper appeared in Ego Update: The Future of Digital Identity, Alain Bieber, ed. (D€usseldorf: NRW Forum, 2015); Christopher J. Lebron, The Making of Black Lives Matter: A Brief History of an Idea (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), 70–72, 154–55; Phillip Luke Sinitiere, “Religion and the Black Freedom Struggle for Sandra Bland,” in “The Seedtime, the Work, and the Harvest”: New Perspectives on the Black Freedom Struggle in America, ed. Reginald K. Ellis, Jeffrey Littlejohn, and Peter Levy (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2018), 197–226.

9. While I recognize that there are other black reparative movements and initiatives such as those associated with the moniker Black Girl Magic, or #BlackGirlMagic, for example, I also have in mind the intellectual inquiry of black futures as it relates to the work of scholars such as Saidiya Hartman, Tina Campt, Fred Moten, Christina Sharpe, and others. In addition to the books and essays the aforementioned scholars have published, in writing this paragraph I had in mind Tina Campt, “Black Feminist Futures and the Practice of Fugitivity,” October 7, 2014, Barnard Center for Research on Women, http://bcrw.barnard. edu/videos/tina-campt-black-feminist-futures-and-the-practice-of-fugitivity/ (accessed February 1, 2018); Fred Moten and Saidiya Hartman’s 2016 conversation with J. Kameron Carter and Sarah Jane Cervanek for the Black Outdoors: Humanities Futures after Property and Possessions series. See “The Black Outdoors: Fred Moten and Saidiya Hartman at Duke University,” October 5, 2016, Duke Franklin Humanities Institute, https://www. youtube.com/watch?v¼t_tUZ6dybrc (accessed August 17, 2017); and Kathleen E. Bethel, “Black Feminist Futures: A Reading List,” Black Perspectives, April 1, 2017, https://www. aaihs.org/black-feminist-futures-a-reading-list/ (accessed August 17, 2017).

10. While space does not allow me to address music in this article, for a reflection on the subject in reference to Sandra Bland, see Phillip Luke Sinitiere, “#SandraBland Soundtrack,” Black Perspectives, August 19, 2016, http://www.aaihs.org/sandrabland soundtrack/ (accessed August 19, 2016). For additional examples of aesthetic responses to Sandra Bland, see the Black Perspectives forum “Remembering Sandra Bland” published in July 2018, https://www.aaihs.org/online-forum-remembering-sandra-bland/ (accessed July 9, 2018).

11. Robin D. G. Kelley, Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination (Boston: Beacon Press, 2002), 1–12, 191–98; Walidah Imarisha, Robin D. G. Kelley, and Jonathan Horstmann, “Black Art Matters: A Roundtable on the Black Radical Imagination,” July 26, 2016, Red Wedge Magazine, http://www.redwedgemagazine.com/online-issue/black-art matters-roundtable-black-radical-imaginatio (accessed August 1, 2017).

12. See, for example, Neil Sapper, “Black Culture in Urban Texas: A Lone Star Renaissance,” in The African American Experience in Texas: An Anthology, ed. Bruce A. Glasrud and James M. Smallwood (Lubbock: Texas Tech University Press, 2007), 248–51; and Sandra M. Mayo and Elvin Holt, eds., Acting Up and Getting Down: Plays by African American Texans (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2014), 3–5.

13. In a perverse irony that names the grotesque and unjust structural arrangements about which Sandra Bland commented, the same Waller County Judge, Albert McCaig, who in April 2016 cleared white Bastrop police officer Daniel Willis of Yvette Smith’s murder, dismissed ex-DPS officer Brian Encinia’s perjury charge in June of 2017. See Tom Dart, “Former Texas Officer Who Fatally Shot Unarmed Woman Found Not Guilty,” The Guardian, April 8, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/apr/07/fdaniel willis-not-guilty-fatal-police-shooting-yvette-smith-texas (accessed August 1, 2017); Jolie McCullough, “Perjury Charge Dropped against Trooper Who Arrested Sandra Bland,” Texas Tribune, June 28, 2017, https://www.texastribune.org/2017/06/28/perjury-charge dropped-against-trooper-who-arrested-sandra-bland/ (accessed August 1, 2017).

14. Kelley, Freedom Dreams.

15. Jeffrey C. Alexander, “Seizing the Stage: Social Performances from Mao Zedong to Martin Luther King, Jr., and Black Lives Matter Today,” TDR: The Drama Review 61, no. 1 (Spring 2017): 28–38; Jeffrey C. Alexander, The Drama of Social Life (Malden, MA: Polity, 2017), 10–38.

16. For a summary of #SayHerName, see Homa Khaleeli, “#SayHerName: Why Kimberle Crenshaw is Fighting for Forgotten Women,” The Guardian, May 30, 2016, https://www. theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2016/may/30/sayhername-why-kimberle-crenshaw-is-fighting for-forgotten-women (accessed October 15, 2017). African American Policy Forum and Center for Intersectionality and Social Policy Studies, “Say Her Name: Resisting Police Brutality against Black Women,” p. 2, last modified 2015, http://static1.squarespace.com/ static/53f20d90e4b0b80451158d8c/t/560c068ee4b0af26f72741df/1443628686535/AAPF_SMN _Brief_Full_singles-min.pdf (accessed October 15, 2017). See also “#SayHerName: An Evening of Arts & Action,” March 28, 2017, http://www.aapf.org/shn/ (accessed October 15, 2017). Relatedly, on Sandra Bland specifically, see Ritchie, Invisible No More, 101, 220.

17. Christina Sharpe, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016), 11. My deployment of language associated around “slavery’s afterlife” comes from Saidiya Hartman, Lose Your Mother: A Journey along the Atlantic Slave Route (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2008).

18. Sharpe, In the Wake,1–11.

19. Ibid., 13.

20. Ibid., 13–14, emphasis in the original.

21. Ibid., 14.

22. Ibid., 20–21.

23. Ibid., 22.

24. While I did not engage the work of Hartman or Sharpe in previous writing on the subject of Sandra Bland, several pieces I wrote at Black Perspectives laid the intellectual foundation for this article. See Phillip Luke Sinitiere, “Sandra Bland (1987–2015): Art, Remembrance, Commemoration,” Black Perspectives, July 13, 2016, http://www.aaihs.org/sandra-bland 1987-2015-art-remembrance-commemoration/ (accessed July 13, 2016) and Sinitiere, “#SandraBland Soundtrack.”

25. “Sandra Bland traffic stop,” July 22, 2015, Texas Department of Public Safety, https://www. youtube.com/watch?v¼CaW09Ymr2BA (accessed September 30, 2017). See also Texas Department of Public Safety’s press release on the video, “DPS Releases Video of Sandra Bland Traffic Stop,” July 21, 2015, http://www.dps.texas.gov/director_staff/media_and_ communications/pr/2015/0721a (accessed September 30, 2017). While I do not take up this issue in the article, readers should recall that several people, most famously film director Ava DuVernay, noted an editing discrepancy in the original DPS dash-cam video. See Ava DuVernay (@Ava), “I edit footage for a living. But anyone can see that this official video has been cut. Read/watch. Why? #SandraBland,” Twitter, July 21, 2015, https://twitter.com/ ava/status/623683526001438720?lang¼en (accessed September 30, 2017); and Jaeah Lee, “Texas Police Deny Editing Dashcam Footage of Sandra Bland’s Arrest,” Mother Jones, July 22, 2015, http://www.motherjones.com/politics/2015/07/sandra-bland-arrest-dashcam video-questions/ (accessed September 30, 2017).

26. Ryan Grim, “The Transcript of Sandra Bland’s Arrest is as Revealing as the Video,” Huffington Post, July 22, 2015, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/sandra-bland-arrest transcript_us_55b03a88e4b0a9b94853b1f1 (accessed September 30, 2017).

27. I adopt “scene of subjection” from Saidiya Hartman, Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997).

28. James McCorkle, “Light You Up,” American Poetry Review 46, no. 3 (May–June 2017): 33.

29. Ibid., 34.

30. Ibid.

31. Ibid.

32. Tiana Clark, “Sandy Speaks,” in Equilibrium by Tiana Clark (Durham, NC: Bull City Press, 2016), 27.

33. Ibid.

34. Ibid.

35. Ibid.

36. Simone John, “Ars Poetica,” in Testify, by Simone John (Portland: Octopus Books, 2017), 53.

37. John, Testify, 55, 60, 63.

38. John, “Lawful Orders,” in Testify, 69.

39. John, “A Woman’s Perspective,” in Testify, 70.

40. John, “I Tried,” in Testify,77–78.

41. John, “Elegy for Dead Black Women #1,” in Testify, 54.

42. John, “The Poet’s Eulogy,” in Testify, 80–82.

43. “Individual World Poetry Slam Finals 2015—FreeQuency ‘Say Her Name,’” Poetry Slam, Inc., March 24, 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v¼64ZQu_RhTTg (accessed July 25, 2017). Patricia Smith also gives voice to Geneva Reed-Veal. See Patricia Smith, “Sagas of the Accidental Saint,” in Incendiary Art (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 2017), 108.

44. Kai Davis, Nayo Jones, and Jasmine Combs, “Sandra Bland,” Button Poetry, May 22, 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v¼QpSC_IusogI (accessed July 25, 2017).

45. Brian Ward, Radio and the Struggle for Civil Rights in the South (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2004); Maurice Berger, For All the World to See: Visual Culture and the Struggle for Civil Rights (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2010); Martin A. Berger, Seeing through Race: A Reinterpretation of Civil Rights Photography (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011); Leigh Raiford, Imprisoned in a Luminous Glare: Photography and the African American Freedom Struggle (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013); Aniko Bodroghkozy, Equal Time: Television and the Civil Rights Movement (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2013); Teresa A. Carbon and Kellie Jones, Witness: Art and Civil Rights in the Sixties (New York: The Monacelli Press, 2014); John Stauffer, Zoe Trodd, Celeste-Marie Bernier, Picturing Frederick Douglass: An Illustrated Biography of the Nineteenth Century’s Most Photographed American (New York: W. W. Norton, 2015); Darcy Grimaldo Grigsby, Enduring Truths: Sojourner’s Shadows and Substance (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015). On Danny Lyon and Ferguson, see Randy Kennedy and Jennifer Schuessler, “Ferguson Images Evoke Civil Rights and Changing Visual Perceptions,” New York Times, August 14, 2014, https://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/15/us/ ferguson-images-evoke-civil-rights-era-and-changing-visual-perceptions.html (accessed March 1, 2017).

46. Simone Browne, Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015).

47. Berger, For All the World to See, 9.

48. “Sandy Speaks—January 15, 2015,” Sandy Speaks, https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v¼f5VhTY3_FC8 (accessed March 1, 2017).

49. Tina M. Campt, Listening to Images (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017). I first thought of analyzing Bland in relation to Campt’s book after reading J. T. Roane, “Fugitivity, Refusal, and Visual Captivity: A Review of Tina Campt’s Listening to Images,” Black Perspectives, May 27, 2017, https://www.aaihs.org/fugitivity-refusal-and-visual captivity-a-review-of-tina-m-campts-listening-to-images/ (accessed May 27, 2017).

50. For more on the context of this religious activism, see Sinitiere, “Religion and the Black Freedom Struggle for Sandra Bland.”

51. “Sandy Speaks—April 8, 2015 (Black Lives Matter),” Sandy Speaks, https://www.youtube. com/watch?v¼CIKeZgC8lQ4 (accessed March 1, 2017).

52. hannahabonner (@hannahabonner), Instagram photo, July 13, 2016, https://www. instagram.com/p/BHz4xbkjlpf/?taken-by¼hannahabonner (accessed July 14, 2016).

53. hannahabonner (@hannahabonner), Instagram photo, July 13, 2016, https://www. instagram.com/p/BHyxWgOjiF5/?taken-by¼hannahabonner (accessed July 14, 2016).

54. John Guess, interview by Phillip Luke Sinitiere, March 2018, Houston, Texas. Digital recording in author’s possession.

55. Ibid.

56. I attended the opening of the Sandra Bland exhibit (and the “Over There Some Place” exhibit discussed below) in February 2018, and subsequently returned to HMAAC several times to revisit the exhibits and interview artists as I further developed this article.

57. Guess interview; Getta Gandbhir and Blair Foster, “A Conversation with My Black Son,” New York Times, March 17, 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/03/17/opinion/a conversation-with-my-black-son.html (accessed May 12, 2018).

58. Guess interview.

59. Ibid.

60. Lee Carrier, interview by Phillip Luke Sinitiere, March 2018, Houston, Texas. Digital recording in author’s possession.

61. I adopt the “cohesive yet ambiguous” quote in this paragraph from “Over There Some Place,” exhibit sign, Houston Museum of African American Culture (Houston, Texas).

62. Carrier interview.

63. Ibid. On the sense of an image’s “present” and its future, see Roane, “Fugitivity, Refusal, and Visual Captivity.”

64. Ibid.

65. Ibid.

Past Editions

1.

“The most unprotected of all human beings”: Black Girls, State Violence, and the Limits of Protection in Jim Crow Virginia

Lindsey Elizabeth Jones

2.

“We will overcome whatever [it] is the system has become today”: Black Women’s Organizing against Police Violence in New York City in the 1980s

Keisha N. Blain

3.

Beyond the Shooting: Eleanor Gray Bumpurs, Identity Erasure, and Family Activism against Police Violence

LaShawn Harris

4.

Care Cage: Black Women, Political Symbolism, and 1970s Prison Crisis

Sarah Haley

5.

Contested Commitment: Policing Black Female Juvenile Delinquency at Efland Home, 1919–1939

Lauren N. Henley

6.

Policing Black Women’s and Black Girls’ Bodies in the Carceral United States

Kali Nicole Gross

7.

The Aesthetic Insurgency of Sandra Bland’s Afterlife

Phillip Luke Sinitiere