VOL. 21

“Tiger Mandingo,” a Tardily Regretful Prosecutor, and the “Viral Underclass”

Steven W. Thrasher

ABSTRACT

DOWNLOAD

SHARE

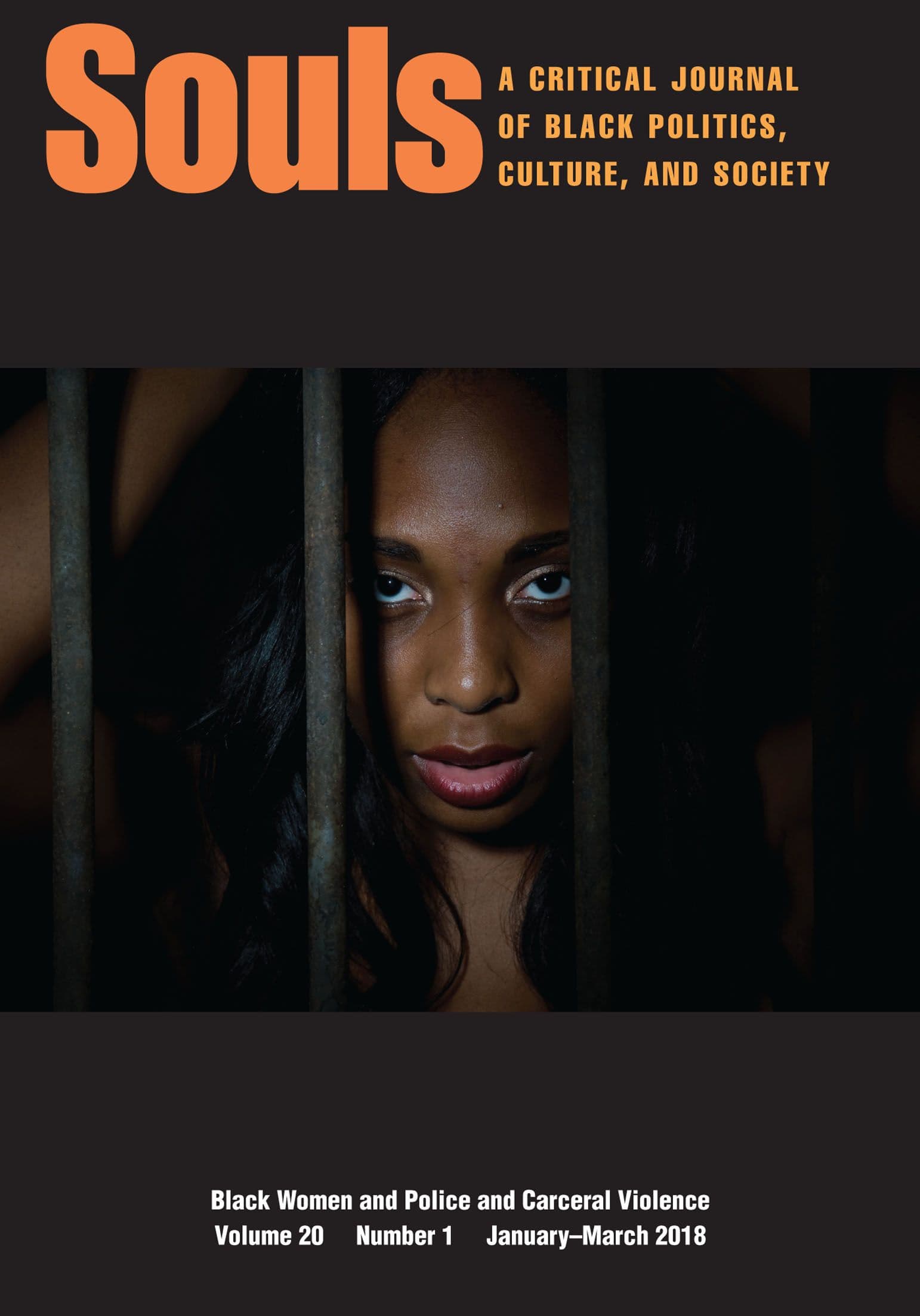

In October 2013, Lindenwood University student Michael Johnson—often known in media by his online and wrestling nickname “Tiger Mandingo”—was arrested in St. Charles, Missouri. Johnson, who is Black, was eventually charged with two counts of “recklessly” transmitting HIV to two men and of exposing four other men to the virus who did not seroconvert. The circumstances of the case were racially charged; four of the six men who pressed charges against “Tiger Mandingo” were white and two of them were Black. St. Charles Prosecuting Attorney Timothy Lohmar mounted an aggressive prosecution against Johnson under the 1988 Missouri AIDS Law, which treats HIV exposure as akin to attempted murder.

In about 30 U.S. states and 70 countries globally,1 governments prosecute people living with HIV for exposing or transmitting the virus to others in a variety of scenarios—including in situations where transmission is unlikely if not impossible (such as in cases of alleged spitting, oral sex, or sex with a condom). These laws persist despite the fact that HIV has been a manageable condition for more than two decades and that an HIV diagnosis needn’t be considered the death sentence it was assumed to be when the laws were first drafted.

In a May 2015 trial in Missouri—despite the fact that no genetic fingerpriting was ever done to link Johnson’s HIV strain to those of his sex partners—Johnson was convicted of transmitting HIV to one of the two men and of exposing HIV to the four other men. He was sentenced to 30.5 years in prison—a sentence longer than the average sentence for second degree murder in Missouri. As one of his sex partners told me, “It would be better for him if he’d killed someone instead.”1

If he had served his entire sentence, Johnson would have been released in the year 2044. However, in part due to my reporting, Johnson was successfully able to connect with grassroots activists (large gay organizations had little interest in him) who helped him to mount a successful legal appeal. In December 2016, a Missouri appeals court overturned Johnson’s conviction due to gross prosecutorial conduct.2 With Johnson’s sentence vacated, Prosecuting Attorney Lohmar could have dropped the charges, especially considering Johnson had been incarcerated for three years already. Instead, Lohmar vowed to go to trial once more and—wanting to avoid the pain of another trial and the possibility of life in prison once again— Johnson took a no contest “Alford” plea deal. He was released from prison on July 9, 2019, after serving nearly 6 years.

In reporting on this case as a journalist and in researching it for my dissertation over five years, I consistently found that Johnson’s prosecution had a great deal to do with race. It was not the whole personhood of Michael Johnson on trial as much as it was the cartoon of “Tiger Mandingo” on trial: a pathologized, hypersexualized, Black predator “top” with a large Black penis (photos of which were shown to the jury) which ejaculated HIV-positive semen into feminized, “innocent,” usually white “bottoms.” This was the dynamic in court. Even though Johnson and his sex partners all had consensual unprotected (or “bareback”) sex, only Johnson was responsible in the eyes of Missouri law—legally because he was HIV-positive and, functionally, because he was Black. In my research in Missouri, I found that as in other U. S. jurisdictions3,4 and in other nations,5 HIV prosecution is closely tied to racism and anti-Blackness. Consistently, in the U.S. and around the world, Black men are prosecuted for HIV at disparate rates and—when convicted—are subjected to harsher and longer sentences.

During the years Michael Johnson has been in prison, the politics surrounding HIV criminalization in the U. S. have shifted significantly. States such as North Carolina and California have downgraded punishment and/or updated their HIV laws so that they are no longer based solely on 1980s science, and they now take into account how antiretroviral drugs (ARVs) transformed HIV into a highly manageable condition.6 There is even significant movement in Missouri to modernize the laws so that people who are on medication and “virally suppressed” cannot be prosecuted in the same way people who are not virally suppressed can be. Yet what these updates have in common is an inherent anti-Blackness: they attempt to decrease the criminalization of people living with HIV who are virally suppressed, while concentrating carceral punitive measures among those who are not virally suppressed. This creates what the activist Sean Strub and others living with HIV call a viral underclass: a class of people whose viral loads have not been reduced and, thus, who could still be prosecuted for exposing HIV to other people under reformed laws.7

But who makes up this viral underclass? People who do not have health insurance, who are homeless, who do not see doctors regularly and—as research has shown—people who are young Black men.8 The viral underclass mirrors the economic underclass of American society. Since research has shown that HIV laws do nothing to decrease rates of transmission9 and exist, then, only to increase stigma (which stymies public health efforts), there is no legal, ethical, or epidemiological justification for continuing to prosecute ableist, racist HIV laws which “only” punish this viral underclass.

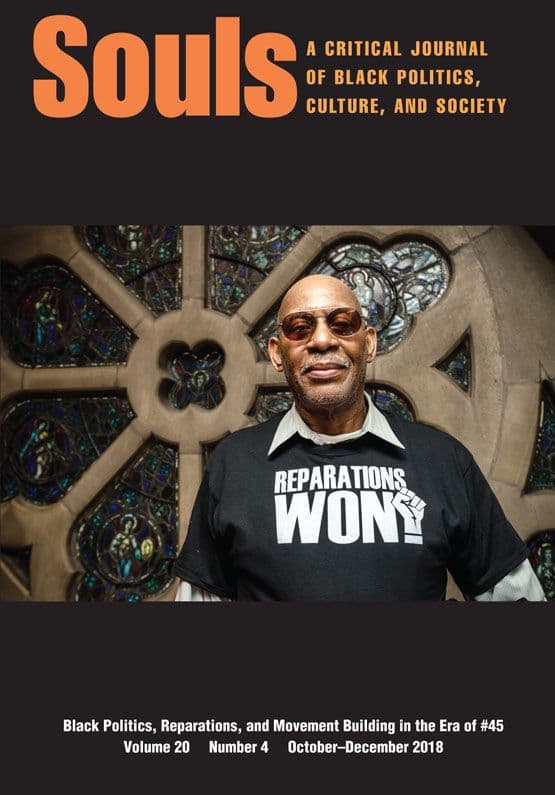

Outrageously, one of the proponents for modernizing the HIV laws in Missouri is St. Charles County Prosecuting Attorney Timothy Lomhar. At a February 2019 hearing in the Missouri Assembly,10 Lohmar testified about “a case a few years ago that got a lot of national attention, and it wasn’t in a good way” which he found to be “embarrassing.” Lohmar testified the Missouri AIDS Law was “antiquated, outdated, and based upon something that science would prove is not accurate.” Lohmar argued that he himself had been “hamstrung” and “forced” to prosecute Johnson under this law—and that he had been “ignorant” of the science when he’d prosecuted Johnson. But this was not true. Many people tried to tell him about HIV science prior to the Johnson trial, including in a high profile, public letter to him signed by Director of Community Medicine for the St. Louis County Department of Corrections.11 Lohmar himself wrote an Op-Ed in the St. Louis Democrat defending his prosecution12—something no law mandated. He did not need to seek life in prison nor dedicate such lavish resources to Johnson’s first trial, and—once Johnson’s conviction was overturned due to Lohmar’s office’s prosecutorial misconduct—Lohmar did not have to threaten to take the case to trial again and could have dropped charges for Johnson’s time served.

And despite the contrite tone in his testimony, Lohmar did not name, let alone apologize to, Michael Johnson, who was then still in prison.

As Maxx Boykin of the Black AIDS Institute put it, full decriminalization of HIV is needed, as HIV reform laws can never “modernize our way to liberation.” If Missouri legislators (and others) merely move toward concentrating shame and punishment within the viral underclass—rather than making sure people in that underclass have what they need to avoid risk of HIV, such as medication, shelter, and employment—then the same racist disparate harm done to Michael Johnson will continue to be done to Black Americans living with HIV.

WORKS CITED

1. Matthew Weait, “The Criminalisation of HIV Exposure and Transmission: A Global Review Working Paper prepared for the Third Meeting of the Technical Advisory Group,” United Nations Global Commission on HIV and the Law, 7–9 July, 2011.

2. Steven Thrasher, “A Black Body on Trial: The Conviction of HIV-Positive ‘Tiger Mandingo,’” BuzzFeed News, December 1, 2015, https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/ steventhrasher/a-black-body-on-trial-the-conviction-of-hiv-positive-tiger-m (retrieved June 7, 2019).

3. Missouri Court of Appeals, Eastern District. State of Missouri v. Michael L. Johnson: “Accordingly, we find that the trial court abused its discretion by admitting recordings of the excerpted recordings of the phone calls Johnson made while in jail. Johnson’s first point is granted, and we reverse and remand for a new trial.” December 20, 2016 https:// www.courts.mo.gov/file.jsp?id=108378 (retrieved June 7, 2019).

4. Carol Galletly and Zita Lazzarini, “Charges for Criminal Exposure to HIV and Aggravated Prostitution Filed in the Nashville, Tennessee Prosecutorial Region 2000–2010,” AIDS and Behavior 17, no. 8 (2013): 2624–36, https://bit.ly/2OduHk5 (accessed June 7, 2019).

5. Amira Hasenbush, Ayako Miyashita, and Bianca Wilson, “HIV Criminalization in California: Penal Implications for People Living with HIV/AIDS (2015),” The Williams Institute, University of California, LA, School of Law, June 2016, https://bit.ly/2y867wz (accessed June 7, 2019).

6. Steven Thrasher, “Tiger Mandingo,” Who Once Faced 30 Years In Prison In HIV Case, Gets Parole”: “In California last fall, Gov. Jerry Brown signed a bill reducing HIV exposure from a felony to a misdemeanor. And in North Carolina earlier this year, activists successfully lobbied to change that state’s HIV laws to take into account contemporary HIV science, reflecting, for example, that people who are properly medicated cannot transmit the virus.” BuzzFeed News, April 9, 2018, https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/ steventhrasher/tiger-mandingo-hiv-michael-johnson-parole (retrieved June 7, 2019).

7. Sean Strub, “Prevention vs. Prosecution: Creating a Viral Underclass.” POZ, October 18, 2011, https://www.poz.com/blog/prevention-vs-prosec (accessed July 10, 2019).

8. Pranesh Chowdhury, Linda Beer, Luke Shouse, and Heather Bradley, “Clinical Outcomes of Young Black Men Receiving HIV Medical Care in the United States, 2009–2014”: “Viral Suppression among Young [B]lack Men during 2009–2014 Was Lower Than among the Overall Population Receiving HIV Care in 2013 (36% vs. 68%),” Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, February 13, 2019, https://bit.ly/2CjfAAC (accessed June 7, 2019).

9. Patricia Sweeney, et al., “Association of HIV Diagnosis Rates and Laws Criminalizing HIV Exposure in the United States,”AIDS 31, no. 10 (2017): 1483–8, doi: 10.1097/ QAD.0000000000001501, https://journals.lww.com/aidsonline/toc/2017/06190 (retrieved June 9, 2019).

10. Timothy Lohmar, February 4, 2019: “My name’s Tim Lohmar. I’m the St. Charles prosecutor, I’m also the president of the Missouri Association of Prosecuting Attorneys. I agree that the time is now to update these laws that criminalize the behavior that’s been outlined. I had a case a few years ago that got a lot of national attention, and it wasn’tin a good way. I was hamstrung in a sense because I was forced to operate under the current laws that we now have. Which I would agree are antiquated, outdated, and based upon something that science would prove is not accurate. So, I think this is the time to for us to take these considerations I have worked with Representative [Holly] Rehder [a Republican who sponsored the update bill, and who also supports needle exchange] over the past year or so, in trying to help her come up with some of the language that’s in here. That we as prosecutors feel comfortable with. She’s correct that the ‘knowingly’ standard is much more in line with our current criminal statutes, as opposed to our current version of acting in a reckless manner. I think, one of the points I would like to make on behalf of prosecutors statewide, we don’t want to have to use the statute to charge someone with a crime. We are, we would be, looking for ways not to do that. However, the facts present themselves in such a way that we have no choice but to pursue justice by filing a charge, we will do that. We need better tools. House bill 167, in my opinion … satisfies those concerns. It does give us some teeth where teeth are needed, but it also modernizes the laws. I can just tell you again, and I’ll wrap up momentarily: the case I had that received that national attention, it was quite embarrassing, to be honest with you. When I looked at some of the issues that were being raised. Being presented with some of the science, I just was ignorant. So, I’m asking you to support these joint efforts, and your state prosecutors are fully behind.”

11. Fred Rottnek and Jeanette Mott Oxford, Aaron Laxton, the Missouri AIDS Taskforce, the Missouri HIV Criminalization Network, the SERO Project, Sean Strub, Terry Lowman, Carrie E. Foote, PhD, Reginald T. Brown, Peter Staley Jay Blothcer, and JD Davids to Timothy Lohmar, April 21, 2015, https://bit.ly/2TLY3LF (accessed March 15, 2019).

12. Tim Lohmar, “Commentary about Michael Johnson Case Was Inaccurate, Misleading,” St. Louis Democrat, August 15, 2015, https://bit.ly/2TIklyH (accessed June 7, 2019).

Past Editions

1.

“Tiger Mandingo,” a Tardily Regretful Prosecutor, and the “Viral Underclass”

Steven W. Thrasher

2.

Black Harm Reduction Politics in the Early Philadelphia Epidemic

J. T. Roane

3.

Black Lesbian Feminist Intellectuals and the Struggle against HIV/AIDS

Darius Bost

4.

From “at Risk” to Interdependent: The Erotic Life Worlds of HIV+ Jamaican Women

Jallicia Jolly

5.

Guest Editors' Note

Marlon M. Bailey & Darius Bost

6.

Homecomings: A Meditation on Military Medicine and HIV

Marlon Rachquel Moore

7.

Interview with Celeste Watkins-Hayes

Darius Bost & Marlon M. Bailey

8.

Interview with Raniyah Copeland, President and CEO of the Black AIDS Institute Discussing Black Feminist Leadership, and Black Women at Risk

Anndretta Lyle Wilson

9.

Live and Let Die: Rethinking Secondary Marginalization in the 21st Century

Lester K. Spence

10.

Poetry

Jericho Brown

11.

Requiem for a Sunbeam

Johari Jabir

12.

Self-Record

Dagmawi Woubshet

13.

Souls Forum: The Black AIDS Epidemic

Marlon M. Bailey, Darius Bost, Jennifer Brier, Angelique Harris, Johnnie Ray Kornegay III, Linda Villarosa, Dagmawi Woubshet, Marissa Miller & Dana D. Hines

14.

The Brad Johnson Tape, X - On Subjugation, 2017

Tiona Nekkia McClodden