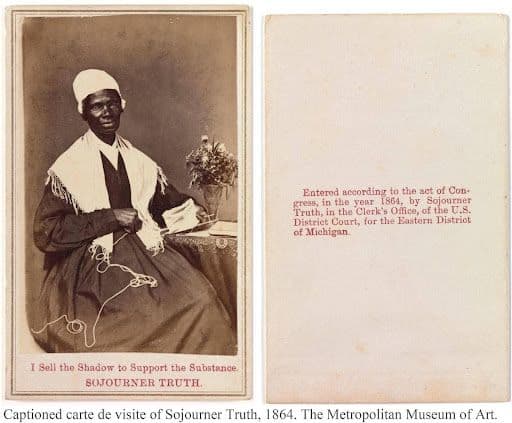

Captioned carte de visite of Sojourner Truth, 1864. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

I sell the Shadow to support the Substance. — Sojourner Truth, carte de visite,

In 1867, Sojourner Truth—abolitionist, Women’s suffragist, prophet, and former slave—subjected herself to a skull reading, a popular practice of scientific and moral examination in the 19th century The measurement of human skulls to indicate capacities for intellect and character, otherwise known as “phrenology,” aligned with racial typologies critical to Western pseudo-scientific study and imperial warfare. For visual artists, the size, shape, and character of the head served as a record of individuality, particularly through portraits and silhouettes Phrenology, art, and reason notably converged in Josiah Nott’s and George Gliddon’s Types of Mankind (1854), where three illustrated skulls are categorized and ranked: “Young Chimpanzee,” “Negro,” and “Apollo Belvedere. The artist depicted the chimpanzee and the Negro in an exaggerated realist fashion, paying sharp attention to creased and shaded skin, course hair texture, bulbous facial features, and piercing eyes. The Greek type, on the other hand, is exemplified by a distinct reference to a classical Greek bust: minimal cross-hatching below the chin to sculpt definition into a smooth marble skin surface; elongated waves and layered curls to comprise fine hair; thin and small facial features, and only the suggestion of an eye—no iris, no pupil. The chimpanzee and the Negro are types. The Greek is a form, signifying the evolved faculties of art and reason supposedly characteristic of the European race. An 1863 article in Phrenological Journal notes that one can recognize “uncultured whites” by their “negro features,” the “negroness” accounting for the degenerate mutation in an otherwise civilized species Negro features—in the white imperial imaginary—denote the primeval ontological defect. Even still, Sojourner Truth wanted a reading.

Truth sought out the phrenological expertise of an abolitionist named Nelson Sizer Art historian Darcy Grimaldo Grigsby provides direct passages from Sizer’s report on Truth’s skull:

You have a moral firmness of character [ … ] you have Conscientiousness, and the love of justice [ … ] you are hopeful, always expecting something favorable in the future [ … ] you have the love of praise [ … ] your self-reliance enables you to do your own thinking and planning [ … ] you have very strong parental affection—you have the motherly feeling, and children and pets like you [ … ] you have courage, but you are not quarrelsome [ … ] more thorough, than noisy, or quarrelsome, or disagreeable [ … ] you have an excellent memory of faces [ … ] you have a natural good talent for figures—can reckon money and do it very straight and correctly [ … ] you are ingenious—could learn to use tools, and be a good mechanic [ … ] you are upright by nature.

Sizer lauds Truth for having a most virtuous and industrious moral character. His reading holds an air of divinity, uncharacteristic of the precision and rationalism required of an effective performance of science. As Grigsby interprets, Sizer’s report is completely “[absent] of physiognomic description or racial reference” and “the report is entirely unmoored from [Truth’s] physical body. Phrenology claimed to reveal social and moral traits simply from the sitter’s unique physical make-up. But Sizer eliminates Truth’s body from the field of descriptive legibility and idealizes her moral character, his reading most likely informed by Truth’s shining reputation among fellow abolitionists and not the features of her skull. The abolitionist saw what he wanted to see: not a black woman but an impressive peer, and the two could not exist in one body. So, he made his attempt at erasing the black woman’s body from the mind’s eye instead.

Truth could have published her 1867 phrenological report alongside or in lieu of the small portrait photographs she had been sharing and selling since 1864. Instead she continued to produce her famed cartes de visite, each one emblazoned with the message “I Sell the Shadow to Support the Substance,” until her death in 1883. Truth ordered more than 200 copies of her portraits from Detroit photographer Corydon C. Randall, suggesting her continued investment in her public image After her death, photographer F.E. Perry of Battle Creek, Michigan reproduced one of Randall’s photographs of Truth, but with a difference. He replaced Truth’s “I Sell the Shadow to Support the Substance” text with his own name and studio location. Another late Truth carte de visite features the information of different photographer in place of her original message. Grigsby’s archival discoveries reveal that at least two photographers capitalized on Truth’s posthumous popularity by pushing their own advertisement and authorship

Sojourner Truth’s corporeal and authorial erasures in the aforementioned visual moments exemplify the enduring legacies of subjection inflicted upon Black women. Yet, these erasures—the erasure of the body, the erasure of the caption— also stimulate the very problem-space of the visual that Truth came to utilize and exploit in her own right. Her contemporary Frederick Douglass believed that the truth of pictures and the recuperation of the black image could promote moral progress. On the surface of their portraits, canonical in African American history and culture, Truth seems to share in this commitment to dignified selfpresentation as a practice of black freedom. Both Douglass’s and Truth’s engagement with photography and its self-making potential has been well-documented and treated by scholars, including Deborah Willis, Nell Irvin Painter, Henry Louis Gates Jr., Maurice O. Wallace, and Sarah Lewis. Truth, in particular, as Grigsby demonstrates, used the instruments of publishing and imaging accompanying photography—copyright, dissemination, replication—for radical ends over the course of her life. I want to suggest that one of these radical ends includes a retheorization of blackness and the fundamental terms of the visual sphere itself. My impulse toward the theoretical terms of black visuality in the 19th and early 20th centuries aligns with scholars Jasmine Nichole Cobb, Leigh Raiford, Ivy G. Wilson, Courtney R. Baker, and Nicole Fleetwood. Building from these scholars, I want to theorize Truth in ways that gives credence to the complexity of her photographic thought and practice, and in ways that might trouble the currency that the terms of dignity, self-presentation, and self-possession have had in the way we describe, interpret, and politicize black images.

First, I reposition Douglass and Truth in the historical moment where photography began to take on new social and political import. Then, I trace Truth’s investments in the visual—in photograph and in presence—by calling on black feminist visual study, and the line of thought that is invested in the politics of black women’s bodies in the visual field I position Truth as a critical interlocutor for how we think about blackness, photography, and the work of the visual. My hope is that this essay, in community with others, can help to re-frame and evolve the interpretative frameworks that have been critical to the study of black visual representation to date.

In the nineteenth century, photography provoked an intellectual question: what role could the new technology come to play in modern society? According to historian Jonathan Crary, this photographic horizon, or at least the idea of it, marked a critical shift in epistemic vision. Whereas the 17th and 18th centuries emphasized camera obscura, the mechanics of light and optics preceding photography as a developed medium, the 19th century marked a shift from the landscape of the visual realm to the visual as embodied Echoing Foucault, Crary locates in this modernization of vision and thought the production of manageable subjects through “a certain polity of the body, a certain way of rendering a group of men docile and useful.” Modernization “called for a technique of overlapping subjection and objectification, [bringing] with it new procedures of individualization. That is where visual technologies could be most useful. Race and racialization underwrote the visual grammars of modernity. People who turned to photography in its nascent era experimented with the instruments and grammars of a new modern project, a new pursuit of the photograph as something imbued with the power not necessarily of revelation, but of confirmation: confirming what is already thought to be evident through the body, what is already thought to be known and knowable, rather than producing knowledge itself.

Frederick Douglass thought photography’s evidential potential could be most useful to the project of social and moral progress, and specifically, for demonstrating how slavery’s abolition would be essential to that future. Douglass sat for countless portraits over the span of his life, earning him the superlative of “the nineteenth century’s most photographed American. He theorized photography through a series of speeches on the medium: “The Age of Pictures,” “Lecture on Pictures,” “Pictures and Progress,” and “Life Pictures. Scholars Maurice Wallace and Shawn Michelle Smith emphasize the series’ two primary interventions: “[readjusting the] sight-lines and [correcting] the habits of racist misrecognition and “[exploring] how African-Americans utilized photography in all its cultural forms to represent a new people, a new period, and new modes of black thought. Douglass wanted to use photographs to create an index of the liberated—liberated in stature and spirit if not yet free in body and law.

The 1860s boasted 3000 American photographers, white and black, and many black Americans had their pictures made, both under conditions of force and choice Black subjects included soldiers, teamsters, chimney sweeps, carpenters, blacksmiths, artisans, bricklayers, seamstresses, shoemakers, washerwomen, cooks, gardeners, and midwives For Douglass, even “the servant girl can now see a likeness of herself, such as noble ladies and even royalty itself could not purchase fifty years ago Douglass marveled at this capacity for those in bondage to manifest their own visions of themselves through photography, who they see themselves to be. In the speech “Pictures and Progress,” delivered in Boston in 1861, Douglass proclaimed, “the process by which [one] is able to invent his own subjective consciousness into the objective form [ … ] is in truth the highest attribute of man’s nature. In a modern era where observation stands in for knowledge, ownership constitutes citizenship, and portraiture denotes character, Douglass saw the photograph—as property, as picture—as a technology of freedom, where the very act of appearing in the image constitutes its own form of self-witness, and where the black slave figures as the inheritor of a liberated future.

Portraiture becomes possibility, but Douglass’ vision bears its own limits, one that compromises the otherwise generative philosophy of photography he offers. In his preface for the unissued American edition of Life of Toussaint L’Ouverture, Douglass invokes Oliver Cromwell’s declarative “paint me as I am” in order to foreground and celebrate the revolutionary stature and example of Louverture, “the black patriot, solider, and statesman” who liberated the slaves in the French Colonies Douglass employs the same Cromwell phrase in the “Pictures and Progress” lecture during the first year of the Civil War. Why invoke a 17th century British Imperial leader to talk about the revolutionary figure and to talk about images? If Cromwell said, “paint me as I am,” Douglass says picture me as I am: a composite figure of revolution, leadership, and moral force.

That the liberating potential of the photograph becomes tethered to the figure of revolution exhibits a masculinist hold on both what the politics and the image could be. Jasmine Nichole Cobb argues that black men in the nineteenth century stressed such presentations of masculine dignity and power as part of their claim to citizenship in order to absolve themselves of any association with the servitude and “feminization” of enslavement To pursue liberation is to pursue personhood, which is to say, manhood. Douglass did believe that the servant girl, too, could see a likeness of herself, and so I am not suggesting that Douglass was not considering black women and girls as part of his vision since we know otherwise from his narrative But the tension, here, is not only how the servant girl sees herself, but what kind of vision of freedom her image comes to provoke. How does the servant girl come to signify liberation? What kind of subject is the servant girl willed to be and become from the portrait?

I draw out these questions not to undermine Douglass’ investment in photography, but to say that the theory and the way we continue to use it in Black Studies is unfinished. What is unfinished, I think, is the way that an investment in self-presentation through the mental and physical portrait, for Douglass, remains entangled with a gendered script of personhood. To assert oneself as a portrait is to resist subjection. Picture me as I am. The servant girl sees herself, and it is the self-reflexive, the I, that excites Douglass, that makes him see pictures as objects that refuse the moral and intellectual assault of slavery, which is the idea that the slave maintains no such “I.” Douglass looks to portraiture because he wants the “I” to be self-evident. But I believe there is also another project at work in the visual that is not so much about reaffirming and reclaiming the currency of the “I” as much as its about interrogating the terms and procedures of the visual field entirely. Perhaps we can begin to think not of the pictures and their evidence of progress, but of the visual a particular kind of process. Here, I find it useful to turn back to Sojourner Truth.

To say “I Sell the Shadow to Support the Substance” beneath her portrait, as Truth will do, is to complicate the epistemic and evidential impulse toward photography that Douglass reclaimed and mobilized, and to provoke a play of physical and mental images—of shadows—that mask and preserve a self that needs no confirmation. Even the term “Ain’t I a Woman?” calls into question the politics of the woman-part more so than the status of the I. What if we were to resist that I of black visual politics, in black photography, and pursued instead the complexities and disruptions that black I poses to the visual field and the public imagination in which both Douglass and Truth intervened?

Sojourner Truth’s visual politics and their disruptive force unfold as much through her physical presence and the idea of her in a public imagination as they do through her material images. Before Truth began to sell her cartes de visite in 1864, two fellow suffragists and abolitionists had already begun to craft a picture of the prophet in the minds of their supporters Although her own oral narrative was published as a written text in 1850 in the era of the slave narrative, Truth became known in the public sphere through Frances Dana Gage’s rendition of her 1851 “Ar’n’t I a Woman?”/”Ain’t I a Woman?” speech at a women’s convention in Akron, , and later, in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1863 Atlantic Monthly article “The Libyan Sibyl” during the Civil War period

At the Akron convention, Truth was applauded for doing what few white women “dared” to do according to the convention’s chairperson: “speak in a meeting Truth spoke out against the men’s arguments that women were the “weaker sex” and that male supremacy was ordained by Christian right She insisted upon her specificity as a black woman, whether enslaved or free, as fundamentally unrecognized as “woman” at all. She emphasized this point through gesture, baring her shoulder to signify work and toil. She problematized the notion of feminine frailty that concerned white women because such assumptions and characteristics never applied to Truth anyway—no one helped her over mud puddles or into carriages Gage reflects on the moments leading up to Truth’s :

The leaders of the movement trembled on seeing a tall, gaunt black woman in a gray dress and white turban, surmounted with an uncouth sunbonnet, march deliberately into the church, walk with the air of a queen up the aisle, and take her seat upon the pulpit steps. A buzz of disapprobation was heard all over the house, and there fell on the listening ear, ‘An abolition affair!’ ‘I told you so!’ ‘Go it, darkey!

And after the :

She had taken us in her strong arms and carried us safely over the slough of difficulty, turning the whole tide in our favor. I have never in my life seen anything like the magical influence that subdued the mobbish spirit of the day and turned the sneers and jeers of an excited crowd into notes of respect and admiration.

Gage imagines Truth as a heroic, magical mother who carries white women into their political future. Harriet Beecher Stow, in “The Libyan Sibyl,” imagines Truth as a native prophetess, an inheritor and purveyor of divine truth. As historian Augusta Rohrbach :

The African seems to seize on the tropical fervor and luxuriance of Scripture imagery as something native; he appears to feel himself to be of the same blood with those old burning, simple souls, the patriarchs, prophets, and seers, whose impassioned words seem only grafted as foreign plants on the cooler stock of the occidental mind.

Unlike the phrenologist’s bodiless account of Truth’s character, Gage and Stowe’s interpretations fashion a mythic black female body whose visible and vocal resonance projects extraordinary “magic, a magic that can be weaponized politically. The white suffragists circulated a living image of Truth, the sight and sense of her. It is in her troublesome and captivating image—present and fleshy and so unlike them—where they derive their own political potential. Truth then, oscillates between political subject and exploited object. Perhaps it is from the space between these poles where Truth comes to her phrase, “I Sell the Shadow to Support the Substance,” printed on the bottom of her cartes de visite that she would soon begin selling.

In 1864, Truth takes advantage of the popularity garnered by Stowe’s article by having cartes de visite made to sell and preserve her image after speaking engagements Historian Nell Painter emphasizes Truth’s sartorial choices in these images: clothing of “excellent quality,” “expertly tailored clothing made of handsome, substantial material” whether in gray, or black and white, and Quaker-styl She poses with her knitting or with a cane, and with “tokens of leisure and feminine gentility such as books and flowers” provided by the photographer. Dignified self-fashioning. Still, her image becomes something else in the hands of others, of which Truth may have already been well aware. While trying to raise interest and support for the abolitionist movement at a Women’s Loyal League Meeting, Susan B. Anthony presented one of Truth’s carte de visite portraits, where she stands “with her disabled hand resting on her can alongside what had become a well-known photograph of Private Gordon, an elderly-appearing black man who bore long, thick keloid scars from frequent whippings to his back Anthony invited her audience to “imagine [ … ] that Truth and Gordon were their parents” and to consider whether or not they would subject their parents to such unimaginable harm or let their parents suffer through old age in bondage The mythic mother from Gage’s imagination appears again, not as savior, but as the one who may need saving. Despite Truth’s careful selffashioning, her image continued to be misread and recoded for moral discourse.

The image of Truth in form and picture exhibits something for which a discourse of black dignity and self-possession cannot alone account. When sitting with the spectacle of Truth in the visual sphere, lived and material, the complexity of Truth’s visual project remains open and generative. Truth understood, for instance, the financial possibilities of her image, regardless of whether or not she could convince white viewers of her human dignity. Truth intended to “protect her image” and “maximize profit” not only through the picture, but through copyright Typically the photographer owns the copyright for photographs produced in his studio. While Truth’s cartes de visite bear her portrait, the card itself is another object, open for revision and re-appropriation. By printing her name and her message “I Sell the Shadow to Support the Substance” beneath the photograph, Truth made a claim to ownership over the cards. In 1864, she registered the cards into copyright under her own name in the Eastern District of Michigan Through these processes of image, property, and authorship, Truth invested in the politics of the visual as not only a question of self-presentation, but as a process of material, social, and epistemic production.

Truth’s image was at once corporeal, discursive, and material. Her image was a sign, an interplay of various investments and interpretations. Her image was a spectacle, especially for the white people who marveled at her form, whether in awe, pity, or admiration. For all the things the image did, it did not seem to resolve in one clear, dignified portrait of Truth herself. But By “placing emphasis on authorship as the construction of memory—rather than as verifiable identity,” as Rohrbach writes, Truth was free “to utilize all manner of material and position as a testimony. In other words, Truth’s investment in the image was not about verifying herself, but about opening up possibilities for what the image can do, how, and for whom.

A young woman from Brooklyn once wrote to Truth saying, “You asked me if I was of your race, and I am proud to say I am of the same race that you are, I am colored, thank God for that. The young woman, Mrs. Josephine Franklin, bought many copies of Truth’s cartes de visite for herself and the other women in her family—“as many as she could afford. That Truth asked Mrs. Franklin about her race suggests, maybe, that the two met in person and that Franklin appeared very light in skin tone, as if able to pass. Maybe Franklin once wrote to Truth asking to purchase her images, and Truth wanted to know more about the woman, and maybe about how her image would be used. When writing back to Truth, Franklin confirms their shared racial identity and emphasizes her commitment to Truth’s image work. “I am colored, thank God for that,” she writes with mutual recognition, writing them both into a view of each other.

Taking these visual episodes alongside Truth’s carte de visit and statement “I Sell the Shadow to Support the Substance,” it becomes more clear that Truth’s image is a cypher, an example of what Nicole Fleetwood calls, the racial icon, a black figure whose image and reception holds seismic public value. Fleetwood uses this term to discuss contemporary conditions, but I believe we can trace this insight back to Truth as well. The racial icon is “a venerated and denigrated figure [who] serves a resonating function as a visual embodiment of American history and as proof of the supremacy of American democracy. The work of the racial icon in an American public is to hold and project the tension between the notion of freedom, the acts of suppression that both foreclose and condition the terms of it, and the moral progress and democracy will be the promise that never arrives but will always be kept open through the image. Truth’s image seems to circulate in this mode, certainly for her white supporters. To the black woman who wrote to her and shared Truth’s small portraits, Truth was a star among them, one whose image could offer possibility. It is this attachment between the black image and its political, psychic, and collective usage for viewing publics that I interpret as that “shadow” in Truth’s “I Sell the Shadow to Support the Substance.” The shadow, here, is the work of blackness as discursive material; the visual field as an arena of competing ideas and investments attached to blackness in body and image; and, to paraphrase Fleetwood, the visible black body that always already troubles the dominant visual field. Perhaps we can understand Truth, then, as a visual theorist and practitioner invested not in dignity, but in difficulty; a figure who projects both substance and shadow, finds utility in the fluidity between—or maybe the simultaneity of—the two.

If Truth is indeed invested in the difficulty of the visual field—both in image and in presence—we can place her in company with other nineteenth century figures who hid, who disguised themselves, who concealed themselves, who eluded traceability modalities that have become critical to the study of black esthetics and black cultural history today. Key touchpoints include Harriet Jacobs/Linda Brent in hiding, sometimes in the garret and sometimes in plain sight of her community; Ellen Craft passing as a white man with her black husband, disguising themselves as master and slave; petit marronage and insurgent black sociality. Sojourner Truth’s rupture to the visual field through her insistent and elusive visibility opens up for her a space where a life could be invented; where a sense of substance becomes possible in the shadow of the image and its labors.

Alan Trachtenberg, Photography in Nineteenth-century America (New York, NY: Harry N Abrams Inc, 1991).

Brian Wallis, “Black Bodies, White Science: Louis Agassiz’s Slave Daguerreotypes,”American Art 9, no. 2 (1995): 39–61.

Courtney R. Baker, Humane Insight: Looking at Images of African American Suffering and Death (Urbana & Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2015).

Daphne A. Brooks, Bodies in Dissent: Spectacular Performances of Race and Freedom, 1850–1910 (Durham, NC & London: Duke University Press, 2006).

Deborah Willis, and Barbara Krauthamer, Envisioning Emancipation: Black Americans and the End of Slavery (Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 2013).

Fred Moten, In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003).

Frederick Douglass, “Lectures on Pictures.” Boston Tremont Temple. Speech, 1861.

Frederick Douglass, “Pictures and progress: an address delivered in Boston, Massachusetts, on 3 December 1861,” in The Frederick Douglass Papers: Series One, Speeches, Debates, and Interviews; Volume Three, ed. John W. Blassingame (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1861/1985).

Jasmine Nichole Cobb, Picture Freedom: Remaking Black Visuality in the Early Nineteenth Century (New York: New York University Press, 2015).

Jonathan Crary, Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1990).

Lindon Barrett, Racial Blackness and the Discontinuity of Western Modernity (Urbana, Chicago, and Springfield: University of Illinois Press, 2014).

Maurice O. Wallace, and Shawn Michelle Smith, Pictures and Progress: Early Photography and the Making of African American Identity (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012).

Mia Bay, F. J. Griffin, M. S. Jones, and B. D. Savage, Toward an Intellectual History of Black Women (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015).

Nell Painter, Sojourner Truth: A life, A Symbol (New York: W.W. Norton and Company Inc., 1996).

Nicole Fleetwood, On Racial Icons: Blackness and the Public Imagination (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2015).

Nicole Fleetwood, Troubling Vision: Performance, Visuality, and Blackness (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2011).

Paul C. Taylor, Black is Beautiful: A Philosophy of Black Aesthetics (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Blackwell, 2016).

Shawn Michelle Smith, American Archives: Gender, Race, and Class in Visual Culture (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999).

1Unknown (American). 1864. Sojourner Truth, “I Sell the Shadow to Support the Substance”. Photographs. Place: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, http://www.metmuseum.org. http:// library.artstor.org.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/asset/SS7731421_7731421_11384124.

2Darcy Grimaldo Grigsby, Enduring Truths: Sojourner’s Shadows and Substance (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2015).

3Brian Wallis, “Black Bodies, White Science: Louis Agassiz’s Slave Daguerreotypes,” American Art 9, no. 2 (1995). Smithsonian Institution. University of Chicago Press. 55.

4Ibid., 49.

5Elaine Coburn, “Critique de la raison n'egre: A Review,” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 3, no. 2 (2014): 178.

6Grigsby, 13.

7Ibid., 13–14 & 193.

8Ibid., 13.

9Ibid., 184.

10Ibid., 185.

11For more on black feminist theorizing of the visual field from the nineteenth century to the twenty-first, see Nicole Fleetwood’s Troubling Vision: Performance, Visuality, and Blackness (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2011), Jasmine Nichole Cobb’s Picture Freedom: Remaking Black Visuality in the Early Nineteenth Century (New York, NY: NYU Press, 2015), Courtney R. Baker’s Humane Insight: Looking at Images of African American Suffering (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2015), and Tina Campt’s Listening to Images (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017); for more on the black female body in photography over time, see Deborah Willis’ and Carla Williams’ canonical work, The Black Female Body: A Photographic History (Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 2002).

12Jonathan Crary, Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1990), 70.

13Ibid., 15.

14John Stauffer, Picturing Frederick Douglass: An Illustrated Biography of the Nineteenth Century’s Most Photographed American (New York, NY: Liveright, 2015).

15M. O. Wallace and S. M. Smith, Pictures and Progress: Early Photography and the Making of African American Identity (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012), 9.

16Ibid.

17Ibid., 10.

18Willis et al., 20.

19Ibid.

20Ibid., 1.

21Douglass as quoted by Wallace, 6.

22Theodore Stanton, “Frederick Douglass on Toussaint L’ouverture and Victor Schoelcher,” The Open Court 1903, no. 12 (2010), 759. Article 7.

23Jasmine Nichole Cobb, Picture Freedom: Remaking Black Visuality in the Early Nineteenth Century (New York: New York University Press, 2015), 7.

24F. Douglass, “Pictures and Progress: An Address Delivered in Boston, Massachusetts, on 3 december 1861,” in The Frederick Douglass Papers: Series One, Speeches, Debates, and Interviews, vol. 3, ed. John W. Blassingame (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1985), 472.

25Augusta Rohrbach, “Shadow and Substance: Sojourner Truth in Black and White,” in Pictures and Progress: Early Photography and the Making of African American Identity (Durham, NC: Duke University Press 2012), 89.

26Angela Davis, Women, Race, and Class (New York: Random House, 1981), 60.

27Rohrbach, 89.

28Davis, 61.

29Ibid.

30Ibid.

31Ibid., 62.

32Ibid., 63.

33Rohrbach, 87.

34Ibid., 62.

35Ibid., 90.

36Nell Painter, Sojourner Truth: A life, A Symbol (New York: W.W. Norton and Company Inc, 1996), 187.

37Ibid.

38Willis et al., 54.

39Painter, 187.

40Rohrbach, 90.

41Ibid.

42Ibid., 94.

43Willis et al., 30.

44Ibid.

45Nicole Fleetwood, On Racial Icons: Blackness and the Public Imagination (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2015), 8.

46Nicole Fleetwood, Troubling Vision: Performance, Visuality, and Blackness (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2011).