In a national press conference on January 6, 2021, then President-elect Joe Biden condemned recent rioting in Washington, D.C. That day a group of rioters, many armed, stormed the Capitol building and violently took control of the government structure in response to presidential election results. President-elect Biden lamented, “The scenes of chaos in the Capitol do not reflect a true America, do not represent who we are.” He later continued “Like so many other Americans, I am genuinely shocked and saddened that our nation so long a beacon of light and hope for democracy has come to such a dark moment. Like numerous American politicians and citizens, he conveyed disbelief and disappointment that such violence and chaos unfolded for all to see. But this riot was not unique in United States history. Historians have examined numerous instances of extralegal violence perpetrated by mostly white mobs angered at challenges to the status quo. One such instance took place in Philadelphia in 1836 when a violent mob attacked a collection of abolitionists and burned down Pennsylvania Hall, their newly erected headquarters. The incident was particularly alarming since many viewed the city as a hotbed of liberty in the late eighteenth century and early nineteenth century: a frequent destination for runaway captives, former location of the nation’s capital, and home to one of the largest free black populations in the country.

Thus, both Philadelphia historically and Washington, D.C. contemporarily were cities brought to their knees in many ways by extralegal violence with relatively little in the way of ramifications for perpetrators. Numerous such instances occurred throughout the history of the United States. In fact, numerous violent riots took place throughout the antebellum era alone taking place including in New York, Boston, and Cincinnati, for instance. The burning of Pennsylvania Hall was one of numerous such acts of disorder and terrorism in antebellum Philadelphia. Therefore, Frederick Douglass wrote about rioting as part and parcel to the American past in stark contrast to the shock and sadness communicated by President Biden. Douglass wrote, “Since the burning of Pennsylvania Hall, Philadelphia has been from time to time, the scene of a series of most foul and cruel mobs … No man is safe–-his life–his property–and all that he holds dear, are in the hands of a mob, which may come upon him at any moment—at mid-night or mid-day, and deprive him of his all. Shame upon the guilty city! Shame upon its law-makers, and law administrators! Instead of lament and alarm, Douglass expressed anger and disillusionment. The former captive turned abolitionist’s sentiments were astute, conveying a realistic response to a nation historically plagued by collective disorder quickly forgotten by much of its citizenry. These were not surprising events but part of a historical through line of what scholar Carol Anderson has termed “white rage. This article argues that examining the example of Pennsylvania Hall’s destruction alongside the Capitol insurrection reveals historical trends within violent rioting incited by threats to the status quo of white hegemony.

There is a rich body of scholarship examining rioting in America as it relates to racialized tensions. However, much of this literature focuses on the twentieth century surrounding mob violence in the Civil Rights Movement as well as lynching events. The 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, for instance, has garnered considerable attention in recent years. By comparing incidents of white riots in the nineteenth and twenty-first centuries, this article seeks to expand the historiography surrounding white rage. Indeed historians have paid far less attention to acts of white terrorism in the nineteenth century. The main exception has been scholarship investigating the Wilmington Riot of 1898 when a violent mob attacked black residents and their white allies to overthrow the government of Wilmington, North Carolina after an election. The incident, like the destruction of Pennsylvania Hall, contains numerous similarities to the January 6th attack. Both the Wilmington riot and the Capitol riot were efforts to violently oust a democratically elected government. The central difference, however, was that the white assailants in Wilmington were successful in their goal with the federal government refusing to intervene. Further, the North Carolina rebels attacked both government officials and civilians forcing a mass exodus of black residents along with massive destruction of personal property.

Wilmington, Philadelphia, and Washington D.C. were part and parcel to American history: a history replete with acts of white terrorism aimed at maintaining white supremacy. Carole Anderson is one of many scholars following the footsteps of W.E.B. Du Bois in examining the theoretical and lived realities of collective white violence. Scholars such as Dylan Rodriguez, Sheila Smith McKoy, and Michael J. Pfeifer have recently investigated this phenomenon throughout time and space as well However, in examining the January 6th attempted coup writers Anne Bonds and Joshua Inwood rightly caution us to not limit white supremacy, and the white rage essential to its maintenance, to large scale acts of violence. In the words of Bonds and Inwood, “Yet to locate white supremacy within the realm of militias, mobs, and Trumpism not only misunderstands white supremacy as a structuring relation, but also reinforces it by reducing it to the extraordinary and spectacular, and within the worldview of extremists. Rather, we maintain that white supremacy must be understood as a political economic and racial project that spans ideologies and political commitments within the operations of the liberal, settler state.” As Bonds and Inwood explain, collective acts of white violence garner increased attention in the public consciousness, but they are merely manifestations of pervasive, structural white supremacy with particular historical circumstances which need to be examined to better understand white violence. Power dynamics, therefore, are essential in analyzing white supremacy and white rage. As Bonds and Inwood further detailed, “In theorizing white supremacy, we reject any notion of white supremacy as singular and transhistorical. We posit white supremacy not as a grand, unchanging conspiracy of race, but rather as a relation of power, a historically shifting logic of socio-spatial organization, situated within capitalist social relations and across a broad political spectrum and an array of identities that are mutually articulated. A comparative study of the Capitol insurrection and the burning of Pennsylvania Hall reveal the importance of dissecting these power dynamics in order to unveil the “fuel” of white rage which in many ways remains more pervasive and influential than the “fire” itself.

The Fuel

Like the Washington insurrection, the burning of Pennsylvania Hall was in many ways a culmination rather than a revelation. Indeed the racial violence in Philadelphia during the antebellum era had roots much earlier in the century. The riots were white attempts to establish and maintain white hegemony in response to real and perceived threats to existing social and economic structures. The turn of the century marked a dramatic increase in racial tensions in the city primarily due to the increasing black population. Newly arrived black people mostly came from the South as runaway slaves, though a small portion of the new arrivals were from Hispaniola arriving as refugees from Saint Domingue. The several hundred black refugees from the island were mostly enslaved blacks accompanying French slaveholders. But these captives also brought with them news of the island’s slave insurrection along with the sense of what could be possible in a world of black oppression. Thus many whites were increasingly apprehensive about what they viewed as a massive growth in the black population in the wake of the San Domingue revolt and the resulting importation of black radical mentality

In addition, European immigrants in particular grew increasingly frustrated with free black labor competition. The city’s free black population increased gradually after Pennsylvania passed the nation’s first abolition law in 1780. Though the law did not free any captives immediately after its adoption, many were able to gain their freedom subsequently through its provisions. By the early nineteenth century, the deterioration of race relations was evidenced by white efforts to restrict the civil rights of black residents in formal legislation and efforts to stop additional African Americans from entering the city The fear of black immigrants and economic frustrations soon combined with black demands for equality catalyzing growing white rage not unlike similar tensions prevalent during the Trump Administration almost two hundred years later also fueled, in part, by fear of migrants, apprehensions about demographic shifts, and efforts to silence calls for a more equitable society.

White jealousy of the rising black middle class in the early nineteenth century Philadelphia was demonstrated by caricatures of black people unsuccessfully attempting to mimic upper-class whites which gained popularity throughout the nation. The images frequently mocked poor blacks as well. The racist caricatures first appeared in 1819. The images depicted African Americans wearing exaggerated and ill-fitting clothing. The dialogue in the drawings typically consisted of broken and improper speech to further emphasize that black elites were attempting to enter a world for which they were not suited The words of a white newspaper editor reprinted in a black newspaper accurately reflected the underlying white jealousy of black economic success. The white commentator aired his frustration stating:

Who walks our streets, in a dress and with an air, which our hard working white population cannot afford, and do not assume? We answer the NEGRO! Who, with his lady, occupies the pavement of a Sunday, jostling the white laborer, with whom he may come in contact into the street? We answer the NEGRO

The commentary revealed an escalation of the racial prejudice embodied by popular derogatory caricatures. But the escalation of white jealousy was not limited to more intense dialogue. Economic frustration with black success led to racial violence. As scholar Koritha Mitchell argues in her work on antiblack violence throughout American history, racial violence is best explained through the lens of white hegemony. Hegemony must be constantly reasserted since dominance can never be absolute, according to Mitchell Thus force-filled backlash becomes the inevitable result of the inherent need for power to sustain itself.

Though tensions grew in Philadelphia during the first two decades of the nineteenth century, massive racial violence largely did not begin until the 1830s. In the words of scholar W.E.B. Du Bois in his pathbreaking analysis of the city’s history, “the agitation of the abolitionists was the match that lighted the fuel. Though theorist Carol Anderson uses the term “kindling” as opposed to Du Bois’s “fuel” to refer to the preconditions of white rage, much of the fodder for the racial violence in the city already existed between 1800 and 1830. To be sure, many whites responded to real and perceived threats to the economic and social order through racist insults and proposed legislation limiting black rights. Therefore the city’s large-scale acts of racial violence in the 1830s and 1840s were merely escalations of long present anti-black racism. But as much as the violent behavior was an extension of progressively deteriorating race relations in the city, the riots similarly marked a significant shift into widespread unrest. The Philadelphia riots were white attempts to maintain and reassert dominance over the city’s black population in an urban landscape once at the forefront of imagining a future free of black bondage.

The rise of abolitionism was the final central ingredient to the rise of racial violence in Philadelphia helping to create the kindling for calamity. Frustrated by the seemingly ineffective gradualist techniques employed by early abolitionists, a new, more radical form of abolitionism emerged in the 1830s calling for immediate abolition. The new wave of anti-slavery efforts was marked by calls for immediate abolition within publications such as David Walker’s 1829 Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World and William Lloyd Garrison The Liberator in 1831 In particular, Walker, a free black man likely the son of a captive, called for African Americans to throw off the shackles of oppression and reveal the systemic injustices of White America. In Walker’s words:

If any are anxious to ascertain who I am, know the world, that I am one of the oppressed, degraded and wretched sons of Africa, rendered so by the avaricious and unmerciful, among the whites … I count my life not dear unto me, but I am ready to be offered at any moment, For what is the use of living, when in fact I am dead. But remember, Americans, that as miserable, wretched, degraded and abject as you have made us in preceding, and in this generation, to support you and your families, that some of you, (whites) on the continent of America, will yet curse the day that you ever were born. You want slaves, and want us for your slaves!!! My colour will yet, root some of you out of the very face of the earth!

For Walker and countless other African Americans during the period, black freedom and racial equality were not only possibilities, they were immediate necessities.

As abolitionism became more militant, so too did anti-abolitionist and racist responses. Most white Philadelphians were not merely alarmed by efforts to end slavery. The city was long a center of abolitionist activity led in large part by the early efforts of the Quaker population, and state’s abolition legislation initiated the death of the institution Pennsylvania decades earlier. Therefore, white outrage toward militant abolitionism in Philadelphia was not largely based on slaveholder fears of lost human property. The opposition to anti-slavery efforts arising in the 1830s was instead based on fears of racial amalgamation and black equality. As much as the transformation of abolitionism was a unique factor to the period, a more holistic view reveals a common trend. White rage often builds to contend threats to white hegemony. As calls for equality grow in size, strength, and perceived radicalism so too does the resulting fire of white rage. History is cyclical in this way revealing an archetype that, in many ways, the Washington riot followed as did countless other such instances throughout the nation’s history.

Nevertheless, some abolitionists fearlessly ignored the long-established realities of white rage when building Pennsylvania Hall. The edifice was built as space to aid in the destruction of slavery. William Dorsey, an African American abolitionist who helped found Pennsylvania Hall, announced its purpose in the antislavery newspaper the Pennsylvania Freeman heralding, “being desirous that the citizens of Philadelphia should possess a room, wherein the principles of Liberty, and Equality of Civil Rights, could be freely discussed, and the evils of slavery fearlessly portrayed, have erected this building, which we are now about to dedicate to Liberty and the Rights of man. Abolitionist efforts constituted a threat to the existing social order in the city contributing to the rise of race riots. The riot of 1838 provides a valuable example of white efforts to assert dominance in the face of new wave abolitionism. During the riot, the newly erected Pennsylvania Hall was burned down after an abolitionist meeting. The challenges of abolitionists along with the growing threat of increased racial diversity constituted challenges to the prevailing social landscape in the minds of many white Americans.

Notably, the abolitionist meetings at Pennsylvania Hall were interracial gatherings featuring both male and female speakers: further assaults upon social norms of the period. At the heart of the Philadelphia riot, then, was white rage directed toward interracial efforts to abolish an oppressive system in a space where increased racial equality was on full display in both word and deed These racial and gender considerations added further tinder to the fuel already constituted by calls for black equality, economic tensions, and xenophobia. As Carole Anderson has rightly observed, “The trigger for white rage, inevitably, is black advancement. It is not the mere presence of black people that is the problem; rather, it is blackness with ambition, with drive, with purpose, with aspirations, and with demands for full and equal citizenship. It is blackness that refuses to accept subjugation, to give up. The societal challenge embodied by Pennsylvania Hall in many ways mirrored the interracial protest movement throughout the United States in the latter half of 2020 in response to a number of tragic murders of unarmed African Americans including Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and Ahmaud Arbery. Such cries to rethink systemic oppression garnered violent reprisals both by law enforcement and private citizens alike.

Violent, collective examples of white rage unleashed, therefore, acted as responses to demonstrated challenges to white supremacy. In understanding the resistance of white supremacy to societal change, activist James Baldwin writing in the twentieth century cogently explained this dynamic. Baldwin observed of White America that “They are, in effect, still trapped in a history which they do not understand; and until they understand it, they cannot be released from it. They have had to believe for many years, and for innumerable reasons, that black men are inferior to white men. Many of them, indeed, know better, but as you will discover, people find it very difficult to act on what they know. To act is to be committed, and to be committed is to be in danger. In this case, the danger, in the minds of most white Americans, is the loss of their identity.” He then continued, “Try to imagine how you would feel if you woke up one morning to find the sun shining and all the stars aflame. You would be frightened because it is out of the order of nature. Any upheaval in the universe is terrifying because it so profoundly attacks one’s sense of one’s own reality. Well, the black man has function in the white man’s world as a fixed star, as an immovable pillar: and as he moves out of his place, heaven and earth are shaken to their foundations. Baldwin’s words described wrath driven by fear of lost power and an unknown reality of racial equality. Such an unknown future seemingly “out of the order of nature” constitutes an “upheaval in the universe” to many familiar only with the reality of white hegemony which permeated the nation’s past and continues to permeate the nation’s present. The investment of the white establishment remained and remains the status quo, making the rallying cry of the Washington rioters of “Keep America Great” all the more telling.

The Rioters

The demographics of those rioting provide insight into the fodder which set the stage for violent backlash. In the case of Pennsylvania Hall as in the Capitol attack, rioters were overwhelmingly white and were not limited to merely one economic class. In the 1838 attack, those who seized abolitionists and their building were largely residents from the area’s working class and merchant class. Both groups had vested interests in maintaining the status quo of white supremacy. Working class whites, including increasing numbers of immigrants from Germany and Ireland bulked at labor competition from black workers Since Philadelphia became a hub of abolitionism and black liberty, people of African descent, enslaved and free, flocked to the city from the countryside and surrounding states. White workers already frustrated by the resulting labor competition resisted a reality where abolitionist efforts bore increased fruit and potentially exacerbated these tensions.

Notably, Du Bois framed working class white residents as the driving force of growing violence and vitriol toward African Americans and the abolitionist movement, with middle and upper classes supporting the rising tide. According to Du Bois, “So intense was the race antipathy among the lower classes, and so much countenance did it receive from the middle and upper classes, that there began, in 1829, a series of riots directed chiefly against Negroes, which recurred frequently until about 1840, and did not wholly cease until after the war. However, historian Beverly Tomek has convincingly argued that the city’s merchant class had its own economic motivations for maintaining slavery. Philadelphia merchants wanted to repudiate the reputation of the urban center as a hub of abolitionism and quell any advancement of the movement in efforts to maintain and expand trade relationships with their Southern counterparts. The Panic of 1837, a financial disaster which resulted in a significant depression, further influenced already present economic concerns among merchants and working class whites. Notably, the January 6th revolt occurred as a global pandemic destabilized the nation’s economy, similarly creating a period of palpable economic uncertainty. For the 1838 rioters, Pennsylvania Hall provided a prominent and convenient target for white residents to unleash economic frustrations. The same was true for black communities which were also targeted by white mob violence during the period. In 1834, for instance, over the course of three days, hundreds in a large mob destroyed more than thirty black homes, two black churches, and killed at least one black resident. Given these economic interests it is unsurprising that the state legislature considered legislation to bar black immigration in the 1830s. Lawmakers also passed legislation outlawing black voting in 1838

While the 1838 attackers represented white workers and merchants, the 2021 revolt represented an even broader swath of perpetrators. According to a 2022 quantitative report published by the University of Chicago, Capitol insurrectionists represented a range of occupations and economic statuses with white collar workers outnumbering blue collar workers. Though rioters were overwhelmingly male in both incidents of white rage, this class dynamic was the inverse of the Philadelphia attack where working class whites likely formed the majority of aggressors. The white collar workers in the Capitol insurrection represented a range of professions unlike the Philadelphia merchants seeking to preserve economic ties with Southern contacts. Among the Capitol group, for example, were attorneys, entrepreneurs, and physicians. The Capitol insurrectionists also converged on the site from numerous parts of the nation, both red and blue states, unlike the 1838 rioters who were mostly residents of the state

Among the significant differences between the violent crowds were the weight of political motivations. The Capitol insurrectionists gathered and revolted in support of then president and Republican candidate Donald Trump after President Trump lost the 2020 election. In this way, the Capitol riot was more akin to the Wilmington insurrection of 1898: a coup d‘,etat to overthrow a democratically elected government. Given the limited ability of black Pennsylvanians to vote at the time and the relatively limited political clout of the abolitionist cause in the early nineteenth century, the political motivations of white perpetrators in Philadelphia pale in comparison to those in the Capitol and Wilmington riots

Nonetheless it is worth noting the similarities in political climates in 2021 and 1838, when Andrew Jackson served as president. Numerous commentators have identified and analyzed parallels between the rise and rule of Donald Trump and Andrew Jackson. President Trump notably associated himself and his presidency with Jackson on numerous occasions as well Both presidencies were marked by increased violence throughout the nation and rising racialized tensions. As explained by historian Ibram X. Kendi, “When Tennessee enslaver and war hero Andrew Jackson became the new president as the hero of democracy for White men and autocracy for others in 1829, the production and consumption of racist ideas seemed to be quickening, despite recent Black advances. Similarly in describing Trump’s rise to power, Carol Anderson underscored that, “Trump supporters, therefore, saw their candidate as ‘America’s last chance’ to recreate a nation that reminded them of the good ol’ days. The country’s growing diversity, Obama’s very existence in the White House, and the ever-increasing visibility of African Americans in colleges and corporations had fueled a sense that these gains were ‘likely to reduce the influence of white Americans in society.” Anderson further summarized that “the ubiquitous campaign slogan ‘Make America Great Again’ (MAGA) was, therefore, freighted with heavy racial baggage.

Perhaps most significantly, the largely white populist waves which elected both men to the nation’s most powerful office help us to understand both violent incidents more fully. More essential to the fuel of white rage than specific economic or political motivations are perceived challenges to the status quo of white supremacy. There was the growing sense among rioters in Philadelphia and Washington, DC that their space and place were being marginalized by existential threats. In nineteenth century Philadelphia, white residents decried what they claimed was a city overrun by black immigrants resulting in increased black crime and poverty. However, as historian Gary Nash has revealed after examining the demographic data, the growth of the city’s white population actually outpaced that of the black population. The majority black residents in early nineteenth century Philadelphia were born in the city rather than recent immigrants. Further, as mentioned previously, black society was markedly stratified in the city, with well-to-do African Americans becoming targets of white jealousy. While black labor competition was a reality, claims of black poverty and crime were similarly exaggerated.

Simply put, these threats were largely specters of the white imagination. The same could be said for the contemporary “myth of the disappearing white majority.” According to the erroneous myth, the white majority is increasingly marginalized—from threats without including illegal immigration, along with internal threats including progressive politics. This helps provide the ideological pretext for intervention, including violent intervention, to maintain white influence and ultimately white supremacy

The Fire

The burning of Pennsylvania Hall demonstrated the mentality of white rioters in the antebellum period. The white mob reacted to the racial mixing and threats to white supremacy exemplified by the meetings in Pennsylvania Hall and the new wave of abolitionism in general. The stage was set in Philadelphia. A newly erected building dedicated, as Dorsey noted, to ideals of liberty, equality, and civil rights hosted abolitionists, black and white, male and female, peacefully exposing these very ideals and highlighting societal failure to live up to them. The act of arson occurred on Thursday May 17, 1838, just days after the hall was first opened. The conferences were attended by thousands of the supporters of both races and included speeches from a number of famous anti-slavery activists including Lucretia Mott, William Lloyd Garrison, and Angelina Grimk,e. The white mob first attacked the building in the days preceding May 17th by throwing rocks through the windows and breaking into the building during abolitionist speeches Perhaps the most noteworthy act of racial solidarity and progress at Pennsylvania Hall was embodied by a wedding rather than speeches or other acts of protest. The hall hosted the marriage of white abolitionists Angelia Grimke and Theodore Weld wed by both a white and a black minister in front of a mixed-raced audience. A celebratory event quickly transformed into contention as enraged people outside assaulted the hall and shouted angrily that evening. But what began as a trickle of unrest soon turned into a flood of violence by Thursday evening when a large mob assembled and set the building ablaze. Members of the mob spent the preceding day openly creating a plan to burn down Pennsylvania Hall, yet there was “hardly an effort being made by the Mayor and city authorities to prevent” the act of arson

The role of the state remains vital to understanding the Philadelphia riot. Herein lay another significant parallel in numerous collective violent acts of white rage throughout American history: the passive, and in some cases, complicit role of governmental structures. History tells us that the state frequently permits, and at times encourages, the unleashing of white rage to maintain the established order while dealing callously with those who dare to challenge it. The same was true for the Washington riot where local officials failed to provide sufficient security and hours passed before the National Guard was deployed: a measure the president openly advocated to counter Black Lives Matter Protestors. There were also reports of some police electing to not intervene and some even supporting the insurrection. This lay in stark contrast to the numerous incidents of police violence in the preceding months directed toward protesters throughout the country demanding systemic change and justice for African Americans recently murdered by police

Abolitionists in Philadelphia knew the double standard of state intervention well. After the initial attacks they requested that the mayor provide more security to defend the building and its visitors. The mayor refused and blamed the activists for inciting the mob with their radical ideals His response underscores how acts of white rage find justification in alleged provocation. The abolitionist calls for dismantling inequities constituted contests to social order and therefore occasioned violent response validated by the state’s inaction. The mayor’s failure to act and rationale made clear that his loyalty, and by extension that of the local government, lay with maintaining existing societal conditions rather than supporting even discussions of change, despite risks to the safety of residents and their property.

Philadelphia sheriff, John Goddard Watmough, was similarly inept. In recounting the events of the day before Pennsylvania Hall’s destruction, the city sheriff claimed, “Of the disturbances of the previous night, I had not received the slightest intimation … I found the Hall occupied—many respectable citizens standing about the door in front, and passing in and out—a few noisy boys in the street, and a large number of highly respectable citizens occupying the opposite pavement.” Despite reports of violence that day, he asserted that the crowd consisted of morally upright citizens not constituting a significant threat in his eyes. Sheriff Watmough later claimed that he was promised reinforcements but back up never arrived. Thus the mob assaulted the building and those inside largely without fear of apprehension, hindrances, or reprisals Notably, the sheriff’s comments echo those of President Donald Trump who applauded the moral character of those committing violence against protestors in Black Lives Matter demonstrations and the laudable spirit of Washington rioters In recounting the brazenness of Philadelphia rioters, Garrison recounted that “Thousands were there exulting in the destruction of the Hall, and openly boasting of the share they had in the work.” The unrest continued for multiple days after May 17th in which whites attacked black Philadelphians, damaged an African American church, and set a black orphanage on fire The hope that was once Pennsylvania Hall was engulfed in a fury of frantic backlash.

The Ashes

In direct contrast to the open participation of “thousands” of rioters, the city government later determined that the abolitionists were wholly responsible for the unrest. The “Report of the Committee on the Police” claimed anti-slavery advocates incited the rage of many white Philadelphians because the “streets [were]

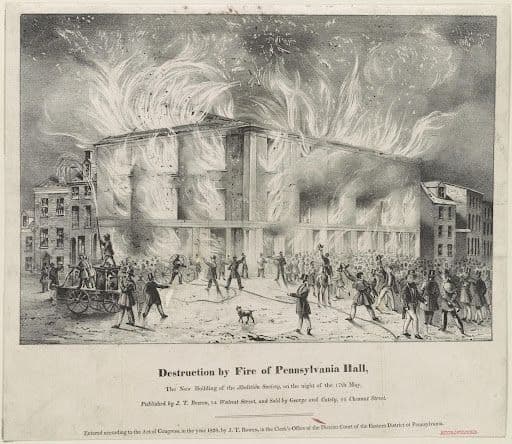

“Destruction by fire of Pennsylvania Hall,” (Philadelphia: Published by J.T. Bowen, 1838). Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

presented for the first time since the days of William Penn, [with] the unusual union of black and white. The words of the report underscored that racial amalgamation was the underlying concern of anti-abolitionism in the city. Further, when activists applied to the government for financial restitution for the sizable investment lost in the newly constructed building’s destruction, their request was only partially granted after years of court battles. Black newspaper, The Colored American similarly expressed the fear of racial integration as the primary cause of the 1838 riot mockingly stating that the mob “preserved society from the horrors of amalgamation by setting fire to the Shelter for Colored Orphans. However, the conclusion of abolitionist writers was that the fault and blame lay within a society that would violently react to peaceful collective discourse postulating a future of racial equality. The white mob set out to reassert dominance over the black population of Philadelphia. The large integrated abolitionist meetings constituted a threat to the established social order by ignoring the racial hierarchy. White rioters responded to the escalated threat by resorting to violence, arson, and unrest.

For activists, black and white, the image of the city as a beacon of liberty, enlightenment, and pride was set ablaze with Pennsylvania Hall. Perhaps, the New York based Colored American conveyed these sentiments most clearly lamenting, “We are astonished at Philadelphia. Her good name is a thing that was. It is gone. Far as has been spread the fame of her excellence, will now be trumpeted the sound of her shame. She is polluted. She has gone the way of a harlot. The quote reflected black disillusionment with Philadelphia during the antebellum period. Notably, given the nation’s history of anti-black violence, African American shock was likely less related to the mob violence than the location of the riot. The city once known for its relatively progressive racial outlook was the site of widespread unrest. As has been discussed, the violence in antebellum Philadelphia had roots at the beginning of the century with deteriorating race relations. The escalation to the racial violence perpetrated in the 1830s and soon after in the 1840s was based on perceived and actual challenges to the prevailing social and economic order. White mobs lashed out in order to establish and maintain hegemony over the black population. But continued black activism and community organization in the city during the antebellum period attested to the resilience of black Philadelphians and their allies.

At first glance, the Washington riot was an insurrection occasioned by an election, but under the surface was far more in the way of fuel. The same was true for the burning of Pennsylvania Hall, which revealed similar unseen complexity. At the heart of both unfortunate events preserving white supremacy remained paramount, as was the case in numerous riots throughout American history. Two edifices planned as bastions of liberty to foster the robust exchange of ideas were defiled in public spectacle. Indeed the attack on Pennsylvania Hall serves as a valuable prism through which to view the Washington attack and the dynamics of white rage. White wrath responded to demands for social equality and systemic change: a regular reality in American history. Thus we are forced to question President Biden’s claim that the Capitol violence did not “reflect a true America.” Indeed his bewilderment was both tied to the location of the chaos at the nation’s Capitol as well as the ways in which such collective chaos conflicts with a national narrative, albeit specious, of an American democracy built upon peace, order, and reason. Instead, such examples of collective white rage in response to demands for structural change arguably remain very true to the historical blueprint of America. Likewise, just days after the Washington insurrection Vox News published a piece titled “Donald Trump is the Accelerant,” which examined how the former president fanned the flames of unrest But the more challenging task than examining the actions of one man is for the U.S. to acknowledge and critically examine the destructive and divisive nature of white rage in the past and present.

The future in the wake of the Washington riot remains unclear, though history does provide some potential insight. While reeling from the violence, Philadelphia activists and abolitionists throughout the nation refused to allow white rage to extinguish the flame of activism. White abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, for instance, trumpeted that “In the destruction of this Hall consecrated to freedom, a fire has in fact been kindled that will never go out. The on-ward progress of our cause in the key-stone State may now be regarded as certain.” He then confidently continued, “abolitionists every where will be stimulated to new efforts, until the destruction of slavery, our own inalienable rights are secured. Rather than smother abolitionist efforts, the burning of Pennsylvania Hall fueled future efforts to end slavery and black oppression. Scholar Carolyn Anderson has recently made a call similar to that of Garrison in response to white rage. “It is time to rethink America,” Anderson proclaims. “This is the moment now when all of us–black, white, Latino, Native American, Asian American–must step out of the shadow of white rage, deny its power, understand its unseemly goals, and refuse to be seduced by its buzzwords, dog whistles, and sophistry. This is when we choose a different future. Anderson like Garrison rightly views white rage as fuel to push forward rather than a reason to capitulate.

While flashpoints like riots remain the most visible demonstrations of collective white violence, we must remember that the tinder was and remains ever-present, merely coming to a large-scale head periodically. The conditions of white supremacy propelling acts of white rage are more significant to unveil than the acts themselves. Specifically, perceived challenges to the status quo of white supremacy trigger white violence. The term “perceived” here remains key. As was the case in both the Philadelphia and Capitol attacks, above all else it was the specter of perceived loss of power in the white consciousness, rather than the reality, that set the stage for white terrorism. Early nineteenth century white Philadelphians claimed the city was overrun with impoverished, criminal prone black migrants. Almost two centuries later, many Capitol insurrectionists saw a reality where white Americans were rapidly marginalized both in terms of demographics and influence. While there were significant differences between the two events, these were populations which feared, in ways not true to reality, a future of diminished white power—where white supremacy would become merely a memory. Thus it is incumbent on American society to remove the tinder of white supremacy if we are to envision a future without acts of white rage. Otherwise the cycle of fuel, fire, and ashes will continue, as it has regularly throughout the nation’s history.

Whether in 1838 Philadelphia, 2021 Washington, D.C., or any of the myriad of similar events throughout American history, such examples of white backlash hold a mirror up to the American populace. The reflection in this mirror, while unrecognizable to some, looks very familiar to those historically marginalized. Thus, a disillusioned Frederick Douglass should be rightly juxtaposed to a disappointed then President-elect Joe Biden. Historical amnesia is oftentimes a racialized privilege. When examining the historical dynamics of such collective chaos, we are forced to echo Douglass’s sentiments “Shame Upon the Guilty City!” However, perhaps a more fitting cry, given the myriad of locations across the nation which have been sites of such violence throughout American history would be: “Shame Upon the Guilty Nation.”

1“President-elect Biden Remarks on U.S. Capitol Protesters,” January. 6, 2021, C-Span, video, 1:33–42; 3:23–8, https://www.c-span.org/video/?507742-1/president-elect-biden-athour-democracy-unprecedented-assault.

2Frederick Douglass, “Philadelphia,” The North Star, October 19, 1849.

3See Carol Anderson, White Rage: The Unspoken Truth of Our Racial Divide, rpt. (New York: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2017).

4See Dylan Rodriguez, White Reconstruction: Domestic Warfare and the Logics of Genocide (New York: Fordham University Press, 2020); Sheila Smith McKoy, When Whites Riot: Writing Race and Violence in American and South African Cultures (Minneapolis: University of Wisconsin Press, 2001); Michael J Pfeifer, Lynching Beyond Dixie: American Mob Violence Outside the South (Baltimore: University of Illinois Press, 2013).

5Anne Bonds and Joshua Inwood, “Relations of Power: The U.S. Capitol Insurrection, White Supremacy and US Democracy,” Society and Space 42, no. 2 (August 9, 2021).

6Gary Nash, Forging Freedom: The Formation of Philadelphia’s Black Community, 1720– 1840 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1988), 173–5; Ira Berlin, “Slavery, Freedom, and Philadelphia’s Struggle for Brotherly Love, 1685–1861,” in Antislavery and Abolitionism in Philadelphia: Emancipation and The Long Struggle for Racial Justice in the City of Brotherly Love, eds. Richard Newman and James Mueller (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2011), 25.

7W.E.B. Du Bois, The Philadelphia Negro: A Social Study (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1996), 26–8; Nash, Forging Freedom, 62–6, 173–5, 181–3; Richard Newman, The Transformation of American Abolitionism: Fighting Slavery in the Early Republic, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002), ch. 3.

8Erica Armstrong Dunbar, A Fragile Freedom: African American Women and Emancipation in the Antebellum City (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008), 132–7; See also Joanne Pope Melish, Disowning Slavery: Gradual Emancipation and “Race” in New England, 1780–1860 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press), 165–82.

9“For the Colored American,” The Colored American, August 18, 1838.

10Koritha Mitchell, Living with Lynching: African American Lynching Plays, Performance, and Citizenship, 1890–1930 (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2011), 3–4.

11Du Bois, The Philadelphia Negro, 25–31.

12Berlin, “Slavery, Freedom, and Philadelphia’s Struggle for Brotherly Love,” 25. See also Newman, The Transformation of American Abolitionism, 7–10; Beverly Tomek, Pennsylvania Hall: A “Legal Lynching” in the Shadow of the Liberty Bell (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), ch. 3.

13David Walker, Appeal, In Four Articles, Together with A Preamble to The Colored Citizens of The World, revised ed. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Library, 2011), 70.

14“Opening of the Hall” The Pennsylvania Freeman, May 17, 1838.

15Tomek, Pennsylvania Hall, 125–6, 133–4.

16Anderson, White Rage, 3–4.

17James Baldwin, The Fire Next Time, reprint (New York: Vintage Books, 1993), 8–9.

18It should be noted that whiteness is a complex historical construction with immigrant groups like the Irish being integrated into white racial categories over the course of the nineteenth centuries. This process has been examined by pioneers of “whiteness studies,” perhaps most notably David R. Roediger and George Lipsitz. See David R. Roediger, The Wages of Whiteness: Race and the Making of the American Working Class (New York: Verso Books, 1991); George Lipsitz, The Possessive Investment in Whiteness: How White People Profit from Identity Politics (Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 1998) More recently Nell Painter has provided a comprehensive analysis of the historical formation of whiteness in her seminal work The History of White People.

19Du Bois, The Philadelphia Negro, 26.

20Ibid, 27–8; Tomek, Pennsylvania Hall, 73–8, 80–2; “Philadelphia Riots–Second Night,” Easton Gazette (Easton, MD), August 23, 1834: 2.

21“American Face of Insurrection: Analysis of Individuals Charged for Storming the US Capitol on January 6, 2021,” Chicago Project on Security & Threats, University of Chicago, 5–15; Scott Tong and Serena McMahon, White, employed and mainstream: What we know about the Jan. 6 rioters one year later,” Here & Now, WBUR NPR January 3, 2022.

22It was not until the 1840s that abolitionist political power and influence began to grow dramatically. See Corey M. Brooks, Liberty Power: Antislavery Third Parties and the Transformation of American Politics (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2016).

23See for example, Steve Inskeep, “Donald Trump and the Legacy of Andrew Jackson,” The Atlantic, November 30, 2016; Dane Strother, “America lived through a Trump-like presidency before, with lasting consequences,” The Hill, February 24, 2019. For a discussion of Trump’s self-association with Jackson, see for example Jenna Johnson and Karen Tumulty, “Trump Cites Andrew Jackson as His Hero,” Washington Post, March 15, 2017.

24Ibram X. Kendi, Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America (New York: Random House Publishing, 169; see also Tomek, Pennsylvania Hall, 76–7. For an analysis of increases in violence during the Trump presidency, see for example Daniel Villarreal, “Hate Crimes under Trump Surged Nearly 20 Percent Says FBI Report,” Newsweek, November 16, 2020.

25Anderson, White Rage, 170.

26Nash, Forging Freedom, 246–8, 272–3. For an in-depth analysis of the myth of the disappearing white majority and its inaccuracies, see Andrew J. Pierce, “The Myth of the White Minority,” Critical Philosophy of Race 3, no. 2 (2015): 305–23.

27Tomek, Pennsylvania Hall, 114–35; “Riot and Arson in Philadelphia,” The Liberator, May 25, 1838.

28William Lloyd Garrison, “PHILADELPHIA, May 18, 1838,” The Liberator, May 25, 1838; Tomek, Pennsylvania Hall, ch. 5–6.

29Jan Wolfe “Trump Wanted Troops to Protect His Supporters at Jan. 6 Rally,” Reuters News, May 12, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/world/us/congresswoman-says-trump-administrationbotched-capitol-riot-preparations-2021-05-12/; Nicole Chavez, “Rioters Breached US Capitol Security on Wednesday. This Was the Police Response When It Was Black Protesters on DC Streets Last Year,” CNN, January 10, 2021, https://www.cnn.com/2021/01/07/us/policeresponse-black-lives-matter-protest-us-capitol/index.html; Anna North, "Police Bias Explains the Capitol Riot," Vox News, January 12, 2021. https://www.vox.com/22224765/capitol-riot-dcpolice-officers.

30Tomek, Pennsylvania Hall, 121–2. See also DuBois, The Philadelphia Negro, 29–30.

31Philadelphia Co., Pa. Sheriff’s Office and John Goddard Watmough, Address of John G. Watmough, High Sheriff, to His Constituents (Philadelphia, PA: C. Alexander, printer, 1838), 5. See also Tomek, Pennsylvania Hall, 121–35.

32Philip Bump, “Over and Over, Trump Has Focused on Black Lives Matter as a Target of Derision or Violence,” The Washington Post, September 1, 2020, https://www. washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/09/01/over-over-trump-has-focused-black-lives-mattertarget-derision-or-violence/; Tommy Beer, "Trump Called BLM Protesters ‘Thugs’ But Capitol-Storming Supporters ‘Very Special,” Forbes, January 6, 2021, https://www.forbes.com/sites/tommybeer/2021/01/06/trump-called-blm-protesters-thugs-but-capitol-stormingsupporters-very-special/?sh=5f52d7113465.

33William Lloyd Garrison, “PHILADELPHIA, May 18, 1838,” The Liberator, May 25, 1838; “Philadelphia Riot,” The Liberator, June 1, 1838; Du Bois, The Philadelphia Negro, 29.

34“For the Colored American,” The Colored American, July 28, 1838.

35“Mob Law at the Capital,” The Colored American, Dec. 22, 1838; Du Bois, The Philadelphia Negro, 29. On the resulting series of court battles see Tomek, Pennsylvania Hall, ch. 10.

36“Philadelphia. Her Good Name–A thing That Was,” The Colored American, June 9, 1838.

37Fabiola Cineas, “Donald Trump is the Accelerant: A Comprehensive Timeline of Trump Encouraging Hate Groups and Political Violence,” Vox News, January 9, 2021, https:// www.vox.com/21506029/trump-violence-tweets-racist-hate-speech.

38“Burning of Pennsylvania Hall,” The Liberator, June 15, 1838.

39Anderson, White Rage, 176, 178.