Who is Dr. Mutulu Shakur? He is known by some as the “stepfather” of rapper Tupac Shakur. This explanation diminishes the significance of a human being who has fought for the liberation of Black people and humanity for nearly six decades. Dr. Shakur is a grassroots organizer, teacher, and defender, anti-repression activist, healer, and unifier of the youth and street forces (whether in the community or inside prison walls) currently living in incarceration. Shakur defines himself as a revolutionary nationalist who struggles for the liberation of the Black nation, which he calls “New Afrika” and is opposed to the oppression of all people in the United States around the globe. He is a resilient spirit who embodies Black peoples’ fight for freedom and human rights. He is a freedom fighter who joins hands with young and old, privileged and poor, academics and “gangstas,” and people of a variety ethnic backgrounds and nationalities. Fighting cancer and a series of other ailments while incarnated, Dr. Shakur is literally fighting for his life. This essay is a brief biography of the activism and political journey of Dr. Mutulu Shakur.

Origins of a Freedom Fighter

Dr. Mutulu Shakur was born Jeral Williams in Baltimore, Maryland in 1950. Many transitions occurred in his early childhood that impacted his political and social development. His mother, Delores Porter became a single parent when he was three-years-old, raising him and his younger sister Sharon. Ms. Porter lost her vision when Jeral was four-years-old. When he was seven, the household moved to the South Jamaica section of the borough of Queens, New York City. As a child, Jeral assumed responsibility as an advocate for his household visual impaired mother to navigate social services. This experience educated him that the system did not work in the interests of poor, working class, and oppressed Black people.

Like many in his generation, the political developments in New York’s Black community, as well as the United States, and globally had a tremendous impact on his social consciousness. African peoples were fighting for their independence from European colonialism on the African continent. The murder of 14-year-old Emmett Till by white supremacists in Mississippi occurred when, young Jeral was five-years-old and heightened the awareness of the reality of white terrorism to his generation and the world. While the Till murder raised public consciousness of white terrorism, the Montgomery Bus Boycott signaled the possibility of collective struggle as a Black community stood in solidarity against segregation for over a year. By the time Jeral was nine-years-old, Black college students launched a massive campaign of civil disobedience that exploded in the system of apartheid in the southern United States (U.S.).

The Nation of Islam (NOI) and its charismatic spokesperson Malcolm X had an impact on New York’s Black neighborhoods, including the thinking of young Jeral Williams. The NOI offered a different response to white supremacy and oppression than the Civil Rights movement demand for full integration and first-class U.S. citizenship. The NOI’s call for a “land of our own” or separate territory from the “white devils” provided an alternative vision for thousands of Black people disenchanted with the hypocrisy of living with state violence and structural racism in the “land of the free.” The NOI had a distribution center for its newspaper Muhammad Speaks in Jerel’s neighborhood. When he was in junior high, the NOI members used their van to transport Jeral and his friends to Harlem’s Temple Number 7 to hear Minister Malcolm, which had a profound impact on their thinking

Malcolm X was assassinated when Jeral was 15 years old. Three years previous, Jeral was welcomed into the home of Aba Saluudin Shakur, an associate of Malcolm X. Aba Shakur was the father of two of Jeral’s friends, Anthony and James Coston (later known as Lumumba and Zayd Shakur) Jeral and his friends also attended the gatherings of the Five Percent Nation of Gods and Earths (aka the Five Percenters) to hear the group’s interpretation of Black freedom and culture. The Five Percenters were formed by a member of the NOI, Clarence 13X Smith, who initiated the Five Percent Nation of Gods and Earth, which had appeal to the Black youth of New York streets. He also participated in the activities of some of his teen-aged peers who organized the Grassroot Advisory Council in South Jamaica, Queens and advocated for resources for youth programs from the government-funded poverty programs.

Jeral Williams made his formal connection with revolutionary nationalist politics at 16 years old after meeting Herman Ferguson, another associate of Malcolm X. Ferguson was a Vice Principal at New York’s P.S. 40 high school and member of Malcolm’s groups: the Muslim Mosque and Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU). He was also responsible for organizing the OAAU’s Liberation School. Ferguson was also the first African American school administrator in South Jamaica Queens. The activist educator worked on the staff at the Evening Center at the Shimer Junior High School where he met Jeral and other South Jamaica youth who were receptive to Black nationalism.

Ferguson exposed the 16-year-old Jeral Williams to a network of newly formed Black Power organizations in the borough of Queens after the assassination of Malcolm X. The first was the Black Brotherhood Improvement Association (BBIA) formed based upon the philosophy of Marcus Garvey and Malcolm X. The BBIA affiliated with the Revolutionary Action Movement (RAM) by 1967. RAM was a national network of revolutionary nationalists, headed by Philadelphia radical intellectual Max Stanford. RAM’s international chairman was Robert F. Williams, the foremost advocate of armed self-defense in the Black freedom struggle. Williams fled the U.S. after trumped-up charges were manufactured against him in North Carolina and received political asylum initially in Cuba and later China. Ferguson also organized the Jamaica Rifle and Pistol Club to provide Black Queens residents training with weapons. He noticed that the white residents of the suburbs surrounding South Jamaica and other Black majority neighborhoods were well-armed and had formed gun clubs Ferguson’s organizing of the Jamaica-Queens gun club was putting into practice a program advocated by Malcolm X and practiced by Robert Williams in Monroe, North Carolina.

As a teenager, Jeral joined the BBIA, RAM, and the Jamaica Rifle and Pistol Club. Ferguson would also emphasize the importance of Jeral and other youth to study history and revolutionary theory. According to Shakur, Ferguson, “introduced me to the works of Kwame Nkrumah, Frantz Fanon, Mao Tse-tung and the teachings of Marcus Garvey and Malcolm. Jeral’s political consciousness was not only Black nationalist, but internationalist, given his mentor’s political education grounded in global anti-colonial and anti-imperialist revolutionary traditions.

Jeral learned the importance of organizing a legal defense and mobilizing to fight political repression early in political activism. The revolutionary nationalist network organized by Herman Ferguson came under attack as a New York Police Department (NYPD) agent provocateur, Edward Howlette, infiltrated the BBIA and became the key witness in a conspiracy case against its members. On June 21, 1967, sixteen BBIA and RAM members, including Max Stanford were charged with conspiracy to commit criminal anarchy. Both Ferguson and BBIA and RAM member Arthur Harris were charged with conspiracy to murder integrationist leaders Roy Wilkins and Whitney Young. Wilkins was the Executive Director and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and Young in the same role for the National Urban League.

Jeral Williams’ responsibility and leadership in the revolutionary nationalist movement in Queens increased during this crisis. He and his friend Anthony Laborde organized a massive rally of 200 in support of Ferguson and Harris in response to their arrests Jeral and Laborde also provided security for leaders of the Friends of the Seventeen, particularly Connie Hicks. Another New York public school teacher and BBIA member, Hicks was the coordinator of the Friends of the 17, developed to raise funds for the BBIA/RAM defendants. Jeral also organized the Committee to Defend Herman Ferguson and Arthur Harris. In October of 1968, Ferguson and Harris would ultimately be convicted of the conspiracy to murder charges by an all-white jury and sentenced to three and half to seven years in prison. His work to free Ferguson and Harris set the foundation for much of his political work he engaged in to free the political prisoners of the Black Liberation Movement.

Allegiance to the Republic of New Afrika

Jeral attended a gathering of 500 Black nationalists in Detroit on March 30-31, 1968, along with Herman Ferguson and Connie Hicks. This gathering, titled the Black Government Conference, was organized by the Detroit-based Malcolm X Society. The Malcolm X Society was organized by associates of Malcolm X, Attorney Milton Henry and his brother Richard Henry. The Henry brothers had hosted Malcolm X on three occasions to address audiences in Detroit and formed the Malcolm X Society after the Black nationalist spokesperson’s assassination to carry out his aims and political vision of human rights, self-determination and self-defense. The African anti-colonial independence movements, the Chinese and Cuban revolutions, and the resistance of the Vietnamese against French and U.S. imperialism also inspired Malcolm, the growing insurgent Black nationalist movement. This internationalism was also embraced and central to the thinking of the Henry brothers.

Malcolm X’s widow, Betty Shabazz, was an honored participant in the Black Government Conference. Other prominent Black Power and Black nationalist leaders were present at this Black nationalist gathering including reparations advocate Queen Mother Moore, Nana Oserjiman Adefumi of New York’s Yoruba Temple, Maulana Karenga of the Us Organization of Los Angeles, Leroi Jones of Newark, New Jersey’s Spirit House, and Hakim Jamal of the Malcolm X Foundation of Compton, California. One hundred of the attendees signed a declaration of independence from the U.S. and proclaimed their allegiance to a new nation-state, the Republic of New Afrika (RNA). The conference identified five deep South states as the RNA national territory and elected a provisional government and accepted Queen Mother Moore’s proposal to name the nation “New Africa.” Ferguson and Hicks were two of the signers of the New Afrikan Declaration of Independence. Ferguson was appointed Minister of Education of the Provisional Government of the Republic of New Afrika (PGRNA).

Ferguson, Hicks, and young Jeral Williams returned to Queens to help build the Republic of New Afrika. Jeral pledged his allegiance to the RNA, becoming a declared citizen of New Afrika. The political objective of a Republic of New Afrika provided a vision and goal for his developing revolutionary nationalist perspective. He was already familiar with Attorney Milton Henry who he heard making addresses at the Black Power Convention in Newark, New Jersey in 1967. He found Henry and his brother Richard to be “passionate speakers for self-determination” and was convinced their perspective of achieving Black power was a more effective strategy for liberation than the 10-point program of the Black Panther Party for Self-defense or community control advocacy of other Black nationalists

Jeral Williams not only decided to choose the national identity of “New Afrikan” but ultimately adopted a new name that reflected his New Afrikan political consciousness. Many members of the New Afrikan Independence Movement (NAIM) adopted African and Arabic names as a symbol of personal and cultural self-determination. For example, Milton Henry became “Gaidi Obadele’’ and his brother Richard “Imari Obadele.” Connie Hicks was re-named the Yoruba name “Iyaluua Akinwole.” Arthur Harris selected an Arabic name “Umar Sharrief.” Jeral Williams too would choose a “New Afrikan” identity by adopting a new name as an RNA citizen—Mutulu Shakur. His first name “Mutulu” was from the Kwa Zulu of South Africa, meaning “someone who helps you get where you are going.” The name “Mutulu” was selected for Jeral by Robert “Sonny” Carson (also known as Mwlina Imiri Abubadika), another of his mentors and leader in the New York Black nationalist and activist community and RNA citizen Jeral also chose the Arabic name “Shakur” (as his last name) from the family name of two of his childhood friends, Lumumba and Zayd, whose father Aba Saladin Shakur was a respected elder in the Black nationalist and Islamic communities. Aba Shakur was Mutulu’s “spiritual father.” The name “Shakur” in Arabic means “thankful.”

Mutulu refers to the former street organization (aka gang leader) Carson as his “street father.” Carson, through his organization the School of Common Sense, provided leadership to Shakur and other PGRNA workers, Black Panthers, Five Percent Nation of Gods and Earths, and other nationalist youth to bring unity to the street organizations (aka youth gangs) in each of New York’s five boroughs, including Brooklyn’s Tomahawks and the Bronx’s Savage Skulls. Part of this work was to develop treaties between the various street organizations and vehicles to resolve conflict

Ferguson for U.S. Senate: A Vote for National Liberation

Mutulu Shakur’s opportunity to participate in an advocacy for New Afrikan national liberation was the campaign to elect his mentor and elder Herman Ferguson to the U.S. Senate as candidate for New York’s Freedom and Peace Party in 1968. The Freedom and Peace Party (FPP) was a left-oriented, third-party effort in the 1968 national and New York state elections. The FPP New York state convention took place in June 1968. Over 500 attended the conference with 97 African American participants, who formed a Black caucus within the state FPP convention. The Black caucus advocated and introduced into FPP platform language concerning opposition to the U.S. military involvement in Vietnam including declaring the U.S. involvement in Southeast Asia as “racist,” demand for immediate withdrawal of U.S. troops and end to aerial bombing, and a statement of solidarity with the National Liberation Front in South Vietnam. The platform also possessed other anti-imperialist demands including condemnation of the military activities of Israel in the “Middle East” and white settler minority rule in Zimbabwe (Rhodesia), South Africa, and Portuguese colonialism in Guinea Bissau, Angola, and Mozambique, as well as ending the U.S. blockade of Cuba. The FPP also called for reforms in welfare rights, repeal of repressive legislation like the McCarran and Smith Acts, community control of police, and amnesty for political prisoners and draft resisters.

The convention named Dr. Benjamin Spock as the FPP candidate for U.S. President and Coretta Scott King as the Vice-Presidential candidate. Herman Ferguson was selected as the candidate for U.S. Senate. Ferguson outlined a Black Power agenda in his acceptance speech including a call for independent Black education, the formation of Black trade unions to represent the interest of Black labor, and bringing home Black troops from Vietnam. Ferguson also used his candidacy as an opportunity to advocate for an independent Black nation-state. He articulated “this is the only viable way to bring able freedom, justice, and equality for the former slaves. Shakur actively participated as an organizer in Ferguson’s campaign as a vehicle to promote the politics of national liberation as an option for Black freedom. The campaign won 10,000 votes in the November 1968 Shakur saw the importance of raising the question of Black self-determination throughout New York state speaking to white people about “supporting right to separate and Black people supporting the need to separate.

One notable development of the campaign was the support of New York’s Black Panther Party for Self-Defense for the Ferguson’s campaign. The national BPP supported the Peace and Freedom Party’s candidacy of Eldridge Cleaver for U.S. President. Ferguson was an elder and comrade of many key leaders of the New York BPP, who also supported his advocacy for New Afrikan independence. The New York BPP’s support for Ferguson’s campaign helped build a bond between the Panthers and the PGRNA in New York

Ocean Hill-Brownsville: From Community Control to Sovereignty

Shakur and other PGRNA workers in NYC also promoted the politics of national liberation in the struggle for community control of schools in the Ocean Hill-Brownsville neighborhoods of Brooklyn, New York. Ocean Hill and Brownsville were predominately Black and Puerto Rican neighborhoods that became the center of a community fight for Black power with national attention. The Ford Foundation proposed a decentralization plan to the New York City Board of Education in response of Black challenges to de facto segregation in the 1960s. The New York public school board adopted the Ford Foundation plan in 1967 to decentralize its massive bureaucracy and create three autonomous districts, one included Ocean Hill and Brownsville. Activists and Black parents and educators in New York viewed decentralization in the Ocean Hill-Brownsville District as an opportunity for community control to challenge disparities and educational inequality and to institute a culturally relevant curriculum for Black students.

Veteran educator Rhody McCoy was appointed the administrator of the Ocean Hill-Brownsville district. McCoy, another associate of Malcolm X, sought to make decisions in accordance with the concerns and demands of Black parents, educators, and activists. On May 8, 1968, the Board ordered reassignment of thirteen teachers and six administrators thought to be undermining the experiment. The predominately white American Federation of Teachers (AFT) protested the reassignments with a walkout of 350 teachers. This conflict mushroomed into a struggle of the Black community asserting its right to control the education of its youth versus the white-controlled and led teachers’ union.

Mutulu Shakur became active in the Black community’s response to the predominantly white teachers’ strike. The community mobilized to keep the schools open and block the striking teachers from returning to the schools. As a worker in the PGRNA, Shakur was active in a broad activist coalition formed to demand Black Community Control and support the local board administrating the Ocean Hill-Brownsville district. The coalition included traditional Civil Rights organizations like the NAACP and the Urban League and Black Power organizations like Sonny Carson’s independent CORE, the Black Panther Party, and the Provisional Government of the Republic of New Afrika. Several Black teachers, particularly members of the activist African American Teachers Association, supported the Ocean Hill-Brownsville board. Shakur and his comrade Black Panther Abdul Majid (formerly Anthony Laborde) worked together to speak to classes and present history, politics, and culture during the teacher’s strike. McCoy spoke of the role of young activists like Shakur and Majid to support the strike:

They’d pick up all of the young people who were late coming to school or trying to play to hook—and kept the drugs out and came into the schools and talked to the youngsters about staying in school, the value of education

Ultimately, New York City Mayor John Lindsay sent municipal police to occupy the schools under the jurisdiction of the local board and by November of 1968, the New York state seized control and abolished the Ocean Hill-Brownsville district.

PGRNA leaders and workers viewed the Ocean Hill-Brownsville struggle in the context of a national liberation struggle and raised the question of Black self-determination and sovereignty. They argued Mayor Lindsay and the New York state takeover of the Ocean Hill-Brownsville district was evidence that “(Black) community control within the U.S. system is impossible. The larger white community will take that away that ‘control’ whenever it pleases them” (Riots, Crimes, and Civil Disorders, 4255). One New Afrikan citizen offered, “If people in Ocean Hill-Brownsville or anywhere else want local control … . the only way to do it is outside the U.S. federal system and as part of the Republic of New Africa. New Afrikan leaders, like PGRNA founder and Minister of the Interior Imari Obadele and Minister of Education Herman Ferguson, argued that the process involving Black parents, students, and residents for community control and grassroots participation prepared the Black neighborhoods of Ocean Hill-Brownsville to take a step toward self-determination. They argued state power was necessary if Black people desired to have control of their schools and any other of the affairs of their community. Independence was essential for Black power.

After the state takeover of Ocean Hill-Brownsville, Imari Obadele and Herman Ferguson lobbied Black educators and activists in Brooklyn about the possibility of organizing a United Nations plebiscite in Ocean Hill-Brownsville to declare it as a territory of the Republic of New Afrika. “Limited sovereignty” for Black people in Ocean Hill-Brownsville would be a forerunner to the campaign to establish independent statehood in the RNA in the southeastern U.S. Independent CORE leader Sonny Carson collaborated with Obadele and Ferguson in developing the Ocean Hill-Brownsville plebiscite proposal. Community meetings for the plebiscite proposal took place at Carson’s School of Common Sense in Brooklyn (Riots, Crimes, and Civil Disorders, 4366). The proposal was based on the thought that a significant number of Black Ocean Hill-Brownsville residents might vote for sovereignty in a United Nations supervised plebiscite, particularly after their demands for community control of their schools were thwarted by the state of New York. The hope was that the international community, through the United Nations, would be obligated to protect the right of self-determination after the people of the predominantly African descendant Brooklyn neighborhoods democratically choose Republic of New Afrika citizenship. The plan included a public safety and defense component, including declaring Ocean Hill-Brownsville an “open city” with no “arms or defensive troops.” It also proposed a health service, hospital, court-system, day care and capacity for print and electronic media, cinema and television production, a public school system, and government-controlled manufacturing industry

A planning meeting was hosted on January 18–19, 1969 in Detroit with national officers on the Ocean Hill-Brownsville project. The PGRNA hosted a March 21 (1969) special election to select ten representatives from Ocean Hill-Brownsville neighborhood to attend its national conference to further discuss the independence project. In spite of police harassment, hundreds of Ocean Hill-Brownsville residents participated in a PGRNA organized special election (with only two weeks’ notice), demonstrating some local support for the project Shakur traveled with this contingent of New Yorkers who attended the national PGRNA National Council of Representatives (or legislature) in Detroit on March 28–30, 1969.

New Bethel: War in America

The conference was held at the historic New Bethel Baptist Church pastored by Reverend C.L. Franklin (father of legendary singer Aretha Franklin). Mutulu Shakur was excited to attend the national gathering and participate in building the PGRNA with other conscious citizens of the New Afrikan independence movement. This was an opportunity for him to experience the PGRNA national leadership and build relationships with government workers from other cities toward freedom, independence and freeing the land of New Afrika. He also worked with the security for the events during the weekend as a part of the PGRNA’s defense force, the Black Legion

An incident occurred at the culmination of the conference that greatly impacted his work in the movement. A conflict ensued after the evening’s activities adjourned around midnight of March 29. Shooting was set in motion after Detroit police officers, Michael Czapski and Richard Worobec, with guns drawn, attempted to intervene with New Afrikans outside New Bethel as PGRNA Vice-President Gaidi Obadele and Queen Mother Moore were leaving. The New Afrikan security responded to what they perceived as a threat from the Detroit police officers. Czapski was immediately killed. Worobec, wounded, fled the scene and signaled for reinforcements. Detroit police responded to news of the shootings by invading the gathering, breaking down the door of the sanctuary, despite sniper fire from an armed clandestine unit in solidarity with the Black Legion. Shakur remembered; “We had retreated to the basement of the New Bethel Church in an effort to hold off the armed assault by the Detroit Police Department. We had run out of means to defend ourselves and were ordered to surrender as we emerged from the basement.

The police utilized overwhelming force to take military control of the church. While police discharged over 800 rounds of ammunition, no New Afrikans or participants in the conference were killed, but four were wounded. Several of the RNA citizens, defense forces, and conference attendees were brutalized and tortured by the raiding Detroit police fueled by violence, revenge, and retaliatory terror. Police particularly concentrated much of their brutality on the RNA security, many of whom were “beaten severely” during the arrests In the midst of the gun battle and police invasion of New Bethel, 18-year-old Mutulu placed Iyaluua Akinwole on the ground and put his body over hers to protect her from harm. According to Shakur the police invasion of the church and violent assault left many of the conference participants “in shock, wounded, and traumatized.

Over 142 conference participants, including Shakur, Herman Ferguson and Umar Sharrief, were arrested after the police invasion overwhelmed the resistance of the New Afrikan security forces. Reverend Franklin and local political activists contacted Wayne County Recorder’s Court Judge George Crockett. Crockett immediately set up temporary court at the police headquarters and released 130 of the arrested New Afrikans, including Shakur, Ferguson, and Sharief. Three members of the New Afrikan security forces, Chaka Fuller, Rafael Viera, and Alfred 2X Hibbits, were charged and tried with murder of Officer Czapski, but acquitted by a majority Black Detroit jury. Viera traveled to Detroit from New York for the gathering. He was a Vietnam-veteran, Puerto Rican Nationalist and member of the pro-independence Young Lords Party, as well as a pledged RNA citizen

The assault at New Bethel served as a critical event in the political development of Mutulu Shakur. He traveled to Detroit to discuss peaceful political processes to achieve Black power and self-determination. The invasion by the Detroit police or what his PGRNA comrade Chokwe Lumumba called “soldier-cops” reinforced the necessity of having a defense capacity to protect the leaders, movement participants, and Black community from state violence and terrorism. Shakur stated in an interview, “I became very clear that question of separating Black people from America … was one of the most dangerous things you could do.” The assault of Detroit soldier cops on the New Afrikan gathering, “crystallized in me that we could not have a movement if we were not prepared to defend ourselves from attack. He returned to New York committed to building New Afrikan security and defense forces to support organizing political action and protecting the Black community.

Internal conflict within the PGRNA suspended the independence movement’s drive for a plebiscite in Brooklyn The PGRNA benefited from the campaign by expanding its activity and growth in Brooklyn in spite of not achieving a UN plebiscite for Black sovereignty and independence in Ocean Hill-Brownsville. Abubadika Carson pledged allegiance to the RNA and worked with Ferguson and Mutulu to build the PGRNA’s Brooklyn’s Consulate. Working closely with Carson, Mutulu significantly contributed to the development of PGRNA work and growth in Brooklyn. Another key recruit in Brooklyn was another associate of Malcolm X, Japanese American activist Mary Kochiyama, who took the New Afrikan oath of allegiance from Herman Ferguson in 1969. The Asian-American Kochiyama was considered a “naturalized” RNA citizen and consistent with her New Afrikan comrades she dropped her “slave name” (Mary) and was identified by her Japanese name “Yuri Kochiyama and Shakur become coworkers in the New Afrikan independence movement.

Shakur taught nation-building and gun safety classes in Brooklyn and recruited RNA citizens and government workers in the borough and also organized the Black Legion, the provisional government’s defense force. He offered PGRNA political education classes in the East Cultural Center in Brooklyn, an institution established by the African American Teachers Association and Black students in 1969 after the conclusion of the Ocean Hill-Brownsville struggle Shakur viewed his nation-building and political education courses as an extension of the Ocean Hill-Brownsville education struggle, the building of independent Black instructional institutions.

Herman Ferguson and Umar Sharrief both decided to seek political asylum outside of U.S. jurisdiction after unsuccessful appeals to their convictions and sentences. Ferguson proclaimed himself a political exile in the Cooperative Republic of Guyana in July 1970. With Ferguson’s exodus from the U.S., Shakur assumed greater responsibility for the direction of the Queens and Brooklyn PGRNA consulates. He was responsible for political education classes-New Afrikan Political Sciencein both locations. In Jamaica-Queens, Shakur conducted political education for both the PGRNA government workers and also the local branch of the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense (BPP), headed by his friend and comrade, Abdul Majid (formerly known as Anthony Laborde). The PGRNA and BPP shared office space and cooperated together. BPP member Freddie Hilton (later known as Kamau Sadiki) remembered learning about the concept of imperialism from Mutulu in a political education session in Jamaica, Queens. Many of the Black Panthers in Jamaica, Queens and in Harlem also became citizens of the RNA and swore their allegiance to New Afrika

Coming to the Defense of Comrades in Crisis

Another ordeal of the United States government’s assault on the Black Liberation Movement occurred immediately after Mutulu Shakur returned from Detroit and the battle of New Bethel. His friends and associates in the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense were arrested on charges of conspiracy in what would be called the New York Panther 21 case. Twenty-one of the leading members of the New York chapter were charged and indicted on 156 various criminal counts centered on conspiracy to bomb police stations, the Botanical Gardens, and commercial establishments in New York city and to carry out sniper attacks on police officers. Mutulu’s childhood friend Lumumba Shakur and his wife Afeni were arrested as part of this alleged conspiracy. Other New York 21 defendants included Richard Dhoruba Moore, Jamal Joseph, Sundiata Acoli, Joan Bird, Baba Odinga, Robert Collier, Curtis Powell, Kwando Kinshasa, Ali Bey Hassan, Kuwasi Balagoon, Richard Harris, Thomas Berry, Lee Berry, Michael Tabor, Lonnie Epps, Abayama Katara. Another comrade, Sekou Odinga, escaped arrest and went underground, eventually emerging in Algeria to receive political asylum with the international section of the BPP there.

The Panther 21 were critical of the Oakland-based leadership of the BPP concerning their support for the New York defendants, their attack on revered Panther comrade Geronimo ji Jaga (Pratt) and other ideological and political differences. The tensions became public after an open letter from incarcerated leaders and members of the New York 21 to the white anti-imperialist clandestine organization, the Weather Underground (a.k.a. “The Weathermen”). The Weather Underground took responsibility in the bombing of political targets primarily related to opposition the Vietnam War. The BPP national leadership expelled the New York chapter in response to the open letter The open letter and subsequent expulsion were major events in what some have labeled the split of the BPP.

Prior to the expulsion and split, Mutulu Shakur joined with other comrades in the revolutionary movement in New York to provide support for the 21 after criticisms surfaced that the BPP national leadership weren’t providing adequate support for their incarcerated comrades. The National Committee for the Defense of Political Prisoners (NCDPP) consolidated a variety of local defense committees to support the 21 defendants and other incarcerated Black Panther, Black Liberation Army, and Black Power activists on the East Coast, including Assata Shakur and Freddie Hilton (aka Kamau Sadiki) The New York 21 trial took eight months with most of the defendants incarcerated for two years during the proceedings. The Panther defendants’ legal team presented a vigorous defense that exposed government infiltration and the use of agent provocateurs to “set up” BPP members by suggesting they engage in acts of violence. After such a lengthy trial, it took the jury 45 minutes of deliberation to acquit the New York defendants.

According to Shakur, Yuri Kochiyama was the “driving force” in the formation of the NCDPP. He told Kochiyama biographer Diane Fujino that New York area Black and Puerto Rican revolutionaries made their “first call” to her if incarcerated. Kochiyama would contact “a lawyer, get information out to … the family (of the captured activist), and the Movement.” She also maintained files and distributed information on the cases of incarcerated movement comrades. Mutulu and PGRNA worker Ibidun Sundiata were key participants of the NCDPP

The NCDPP continued to work to support other political prisoners and prisoners of war, particularly in New York state after their acquittal of the Panther defendants in the 21-court case. The defense committee had a New Afrikan independence orientation as its newsletter was titled Take the Land (TTL), a more militant slogan than the PGRNA’s “Free the land.” TTL highlighted the cases of captured Black Liberation Army combatants, like Dhoruba Moore (Bin Wihad), Assata Shakur, and the New York 3 (Albert Nuh Washington, Herman Bell, and Anthony Bottoms a.k.a. Jalil Muntaqim) as well as New York area and national cases like the Wilmington 10 and the Republic of New Afrika 11. The NCDPP engaged in fundraising, media work, and grassroots awareness campaigns around the cases of political prisoners and mobilized supporters to fill the courtroom for the respective cases in New York and New Jersey. Their support for BLA combatants and other revolutionaries on trial and incarcerated was critical during a period where counterinsurgency efforts by local police and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) had significantly destabilized and disrupted the revolutionary nationalist, pro-national liberation forces of the Black liberation movement.

New York BPP leader Zayd Malik Shakur assigned Mutulu to California in 1971 to check on the well-being and case of incarcerated political prisoner Geronimo ji Jaga (Pratt). Geronimo, aka known as “G,” was a veteran of the U.S. Army—82nd Airborne (serving in Vietnam), who shared his military training and skills to the defense forces of the BPP and other Black Power movement organizations. Besides the BPP, Geronimo trained the paramilitary forces of the Texas and the Alabama Black Liberation Front, the PGRNA, De Mau Mau (composed of Vietnam-era Black veterans), and also underground combatants in the urban and rural communities throughout the U.S. empire After being captured in December 1970 in Dallas, Texas, ji Jaga was convicted of the 1968 murder of Caroline Olsen, a white female elementary school teacher, in Santa Monica, California and sentenced to life. The FBI and the state of California used a variety of dirty tricks to secure the conviction. The prosecution infiltrated ji Jaga’s defense team with an informant who supplied intelligence to the District Attorney’s office. In addition, the main witness in the case perjured himself on the stand. BPP member Julio Butler provided perjured testimony during the trial testifying that ji Jaga admitted killing Olsen. Butler also committed perjury during the cross-examination by defense attorney Johnny Cochran, in response to the question if he was a U.S. government informant. Cointelpro files would later confirm Butler was a paid FBI informant embedded in the BPP. The FBI also withheld evidence of ji Jaga’s whereabouts during the time of Olsen’s murder. FBI surveillance could confirm ji Jaga was 350-miles away from the scene during the time of the crime at a BPP national meeting in Oakland, California. Another crucial development was the BPP leadership labeling ji Jaga as a counterrevolutionary and purging him from the organization. BPP founder and leader Huey Newton was convinced by his government operatives, ambitious party members, and his own paranoia, that ji Jaga was dangerous. BPP leadership could have corroborated his presence in Oakland during the time of the murder but ordered its members not to testify and support the case

Mutulu and the NCDPP considered the Oakland-based, national BPP leadership’s abandonment of ji Jaga, who many considered a hero and revolutionary freedom fighter, as similar to its relinquishment of support of the legal defense of the New York 21. Mutulu knew the role the ji Jaga played in developing fighting forces of Black freedom fighters across the United States, including training the clandestine snipers that aided the Black Legion during the battle of New Bethel in Detroit. He took this assignment to travel to California to check on ji Jaga and his legal case with enthusiasm. Mutulu committed himself to work for the freedom of ji Jaga after meeting him in San Quentin. He recruited a team of activists to work on ji Jaga’s defense, including former BPP New York 21 defendant Afeni Shakur, radical activist and paralegal Yaasmyn Fula, Afrikan Peoples Party (APP) and House of Umoja organizer Watani Tyehimba and revolutionary activist Njeri Khan in Los Angeles

Formation of the National Task Force for Cointelpro Litigation and Research

White radical activists made a tremendous contribution to confirming Black Power activist charges that their organizations, leaders, and members were being arrested, convicted, and incarcerated on trumped-up charges, forced into exile, and targeted for assassinations through a governmental campaign of low intensity warfare. The Citizens Commission to Investigate the FBI broke into an FBI field office in Media, Pennsylvania in 1971 and stumbled upon memorandums and reports documenting surveillance and counter-insurgency activities on movement activists. The release of the liberated files to the media led to a demand to make the FBI’s counter-insurgency documents public and sanctions placed on the FBI for violations of civil liberties and human rights.

Political repression on the NCDPP and the revelation of the FBI’s Cointelpro program and its emphasis on surveillance, disruption, and neutralizing the Black Liberation forces motivated Mutulu, Afeni Shakur and Yaasmyn Fula to build an investigative arm of the Black Liberation Movement, which publicly emerged as the National Task Force for Cointelpro Litigation and Research (NTFCLR) in 1977. The presence of the NTFCLR was announced at a 1978 commemoration of Malcolm X at the Audubon Ballroom in Harlem NTFCLR had an impressive Board of Directors of progressive lawyers including, pioneer radical Black feminist Flo Kennedy and Lennox Hinds of the National Conference of Black Lawyers and scholar-activists Nathan Hare and Noam Chomsky Its staff attorneys included Black Power activist Lew Meyers, McCarthy era-survivor Jonathan Lubell, and anti-imperialist solidarity supporter Susan Tipograph. Mutulu and Afeni Shakur served as National Coordinators of the NTFCLR. Both asserted a Black liberation movement-led investigative arm was a necessity. The NTFCLR utilized the Freedom of Information Act to provide documentation of surveillance, disruption of movement activities, and government misconduct. The research from these detailed inquiries of counter insurgency would support these legal defense efforts of increased numbers of incarcerated revolutionaries like ji Jaga, the Republic of New Afrika (RNA) 11, the Wilmington 10, Assata Shakur, Sundiata Acoli, and other Black Liberation Army defendants. Questions concerning the violent deaths of Black Power movement activists like Fred Hampton, Mark Clark, Alprentice “Bunchy” Carter, John Huggins, Ralph Featherstone, and Che Payne also motivated concentration to determine responsibility and pursuit of justice. NTFCLR was also a vehicle for defense of the Black Liberation Movement as there was intense, continued repression on its activists, particularly the PGRNA and the Afrikan Peoples Party (a successor organization of the Revolutionary Action Movement in the early 1970s). The priority for the NTFCLR was the case of ji Jaga to demand release of the FBI surveillance on him to determine his innocence in the murder of Carolyn Olsen

Revolutionary Doctor: Healing the People

Already active in Queens and Brooklyn, Shakur emerged in the leadership in the grassroots effort of another New York borough, the Bronx. The Puerto Rican revolutionary nationalist Young Lords Party and other insurgent forces led an activist occupation of the Nurse’s Residence Bronx’s Lincoln Hospital in November 1970. This action was the latest of a series of protests by patients, medical professionals, and grassroots activists to address the health care needs of the working class and impoverished people of Black and Puerto Rican Bronx communities. Lincoln Hospital was known in the Bronx as “the Butcher shop” for its substandard facilities and services. The Young Lords and a coalition of grassroots forces emerged in the Bronx to confront the genocidal policies and treatment of Black and Latinx people at the hospital. The November 1970 action led to the formation of the People’s Program to serve the needs of grassroots people combating heroin addiction. Heroin was devastating Black and Puerto Rican people in working class and poor neighborhoods. The People’s Program sought solutions to this plague in the Bronx. Mutulu Shakur and the PGRNA workers he led joined the fight for people’s health care in the Bronx.

Shakur played a critical role in two aspects of the detox project of the People’s Program: political education and the use of acupuncture in the detoxification process. Mutulu Shakur‘s experience as a political education instructor with the PGRNA and BPP in Queens and New Afrikan nation-building classes and for Ocean Hill-Brownsville students in Brooklyn provided him plenty of experience in teaching radical politics to community folks. He was hired by the Lincoln Detox Community Program as a political education instructor in 1970. Lincoln Detox prioritized political education to recovering addicts. Political education was crucial to the recovery since arming the patient with an understanding of the social reality that contributed to their addiction would aid them in combating substance abuse and recidivism. One friend of the Detox program offered the program desired to transform addicts from “victims into revolutionaries. The political education courses drew from 50 to 100 people per session Shakur and other instructors pointed to understanding the social and economic position of addicts in the underground economy and their exploitation by high level drug dealers, organized crime, and pimps, as well as the cycle of violence that harms the community. The Lincoln Detox political education program also targeted the capitalist pharmaceutical industry and its investment in the U.S. government-controlled methadone maintenance program for recovering heroin addicts. They argued not only did methadone have adverse medical effects but was also used to replace heroin addiction with dependency on a new pharmaceutical (methadone) that was controlled by the federal government. This made the U.S.-controlled methadone program another vehicle to control poor and oppressed communities within the empire. Lincoln’s Detox’s position on the debilitating impact and colonial implications of the use of the methadone program on Black and Puerto Rican communities made the clinic a political target of the “for profit,” corporate medical and pharmaceutical industries.

Shakur discovered the efficacy of acupuncture when two of his children were healed through that treatment. This led him to advocate the Lincoln detoxification program explore acupuncture as a vehicle to assist patients with a safe, non-chemical withdrawal from heroin addiction The political grounding of the program was clearly linked to the use of acupuncture to combat addiction. Lincoln’s People’s Program articulated:

We believe that acupuncture will allow for painless withdrawal. These treatments will be combined with our political education and after care programs, housing, vocational, educational, legal, etc.

Since the drag plague is result of the diabolical, avaricious, racist, sexist, and classist nature of this society, acupuncture is no solution. In that it will allow for drugless detox, we believe it will help people to better deal with the root cause of addiction. As a people’s medicine is the big step towards reclaiming control over our own bodies and minds

The Chinese Revolution’s concept of the barefoot doctor served as a model for the Acupuncturists of the Lincoln Detox program Barefoot doctors were healthcare workers trained and imbedded in rural, peasant communities who served previously underserved people in the Chinese Revolution. Revolutionary China promoted this concept to developing nations and liberation movements. The Lincoln Detox healers saw themselves as people’s servants working in the interests of oppressed, working, and poor people. His work of healing at Lincoln Detox became the motivation to pursue becoming proficient and licensed as a doctor of acupuncture. Dr. Shakur became certified and licensed to practice acupuncture in the State of California in 1976. Eventually, he was promoted to Assistant Director of Lincoln Detox.

Lincoln Detox came under vicious attacks as right-wing elements in the federal, state, and local governments and other counter-insurgency forces targeted the revolutionary-led health care institution. Lincoln Detox endured a campaign of Cointelpro-oriented media assaults, physical attacks on medical staff, including the suspicious death of Dr. Richard Taft. Dr. Taft was instrumental in introducing acupuncture to the Lincoln Hospital People’s Program. Taft’s critical role in the

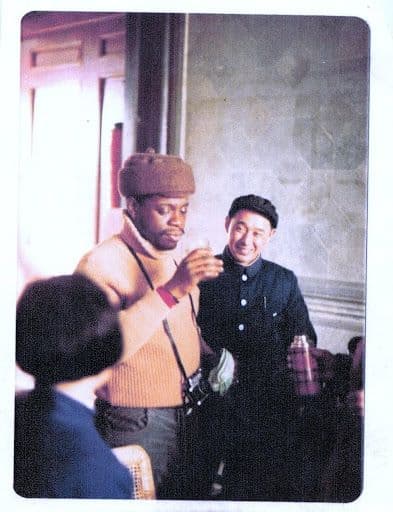

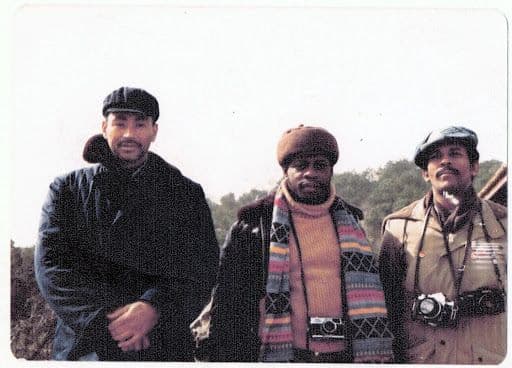

Mutulu Shakur visiting People’s Republic of China in 1976. Photo from personal collection of Dr. Mutulu Shakur.

Richard Delaney (left), Dr. Mutulu Shakur (middle) and host in People’s Republic of China in 1976. Photo from personal collection of Dr. Mutulu Shakur.

Lincoln’s Peoples Program, and advocacy for a non-chemical detoxification made him a target for the pharmaceutical industry and other counterrevolutionary opponents of Lincoln Detox. He began carrying a weapon after surviving a shooting from unknown attackers in August 1974. He was found dead in a hospital closet on October 29, 1974. While “preliminary examination of his body showed no track marks of evidence of drug use,” his death was “officially” declared an overdose

Shakur and other Lincoln Detox staff and associates believed his death was a Cointelpro-oriented political assassination designed to undermine and ultimately destroy the revolutionary-controlled medical program in the Bronx. The fact that, on the day of his death, Taft was scheduled to meet with a federal drug official about the work at Lincoln Detox supported their suspicions. Taft was also specifically a target of the propaganda of the National Caucus of Labor Committees (NCLC) attacking the Lincoln People’s Program. NCLC was a “pseudo-gang headed by the controversial Lyndon LaRoche While characterizing itself as a left organization, the NCLC engaged in counterinsurgency through disruptive actions designed to destabilize Lincoln Detox and other revolutionary movements like Newark’s Congress of African People.

The Mayor Edward Koch and the hospital administration took advantage of the media attacks and internal contradictions at Lincoln Detox to raid the clinic with a force of 200 NYPD officers on November 28, 1978. The real issue was for the city and the hospital to seize control of an autonomous unit operating on revolutionary politics. Revolutionary Puerto Rican and New Afrikan Lincoln Detox staff hired as city employees, like Panama Alba, Walter Bosque, and Mutulu Shakur were all transferred to other city-controlled medical facilities outside of the Bronx

Despite the counter-insurgency assault against Lincoln Detox, by the late 1970s, Shakur’s work in acupuncture and drug detoxification was both nationally and internationally recognized as he was invited to address members of the medical community around the world. Dr. Shakur lectured on his work at many international medical conferences and was invited to the People’s Republic of China. In addition, he developed the anti-substance abuse program for the United Church of Christ’s social justice arm, the Commission for Racial Justice. The United Church of Christ (UCC) founded the CRJ in 1969 with an annual commitment of $500,000.

Mutulu Shakur and another skilled acupuncturist, Dr. Richard Delaney, moved to create an independent clinic and alternative medical school in Harlem, New York after the city shut down the Lincoln Detox program. Shakur and Delaney’s clinic operated as a wing of their organization, the Black Acupuncture Advisory Association of North America (BAAANA). At BAAANA, he continued his remarkable work and also treated thousands of poor and elderly patients who would otherwise have no access to treatment of this type. Many community leaders, political activists, legal workers, and doctors were served by BAAANA and over one hundred medical students were trained in the discipline of acupuncture.

Organizing Self-Defense on the Frontline of the Struggle

The Commission for Racial Justice (CRJ) also employed Shakur to aid Black communities to defend themselves from white supremacist violence. He was engaged in CRJ in support efforts for community activists in two Black communities under siege in the early 1970s, Wilmington, North Carolina and Cairo, Illinois. Both communities were tormented by white supremacist paramilitary groups to repress grassroots campaigns for human rights. Shakur’s training in armed self-defense became a resource for both communities’ need to repeal white terrorist invaders.

The CRJ initiated support efforts for the beleaguered Black community of Cairo in Alexander County in southern Illinois in 1969. African Americans constituted half of the city’s population of 6000 but were meagerly represented in local government or civil service Cairo Black residents suffered from substandard housing concentrated in the Pyramid Courts projects, and low income related to limited employment opportunities in the private and public sector. Black resistance accelerated in Cairo inspired by federal civil rights legislation during the late 1960s. The death of Robert Hunt, a 19-year-old Black G.I. found hung in the local jail, sparked a three-day Black revolt in the city in 1967. The increased activism and Black uprising incited white supremacist reaction, including attacks on the Black community by the White Hats, a racist paramilitary group deputized by the Alexander County Sheriff. Black Power activist and Black liberation theologian Reverend Charles Koen returned to his hometown to serve as the spokesperson and organizer of the Cairo United Front, which led the Black community’s grassroots movement for human rights. The Cairo United Front organized an economic boycott of white enterprises downtown in response to white vigilantes firing rounds of ammunition into the Pyramid Courts for two and a half hours on March 31, 1969. Routine police repression and nightly attacks by the White Hats attempted to break Black resistance and the boycott. The white reaction to Black insurgency increased the necessity of the Black community to organize armed selfdefense for protection and security

The CRJ assigned George Bell, one of its staff, to work with the local movement in Cairo and provided material aid to its Black community. The CRJ joined a national network of Black clergy to provide food and medical assistance to Cairo’s Black community to survive economic isolation and violent terrorist assaults. Mutulu Shakur traveled to Cairo for the CRJ bringing groceries, medicine and other supplies gathered in New York to the Pyramid Courts in 1970. He also brought a PGRNA security team to assist the training and armed self-defense capacity in Cairo to repel white vigilantes. Shakur remembered his group traveling into the Pyramid Courts had to “shoot our way in there” to deliver the material aid to Pyramid Courts

Like Cairo, North Carolina’s Wilmington became a racial hotspot. Wilmington racial situation “heated up” in 1971 sparked by its recently desegregated school system. Wilmington’s Black students initiated protests after an off-campus skirmish of racial violence. After this incident involving Black and white students, only the African American youth were disciplined by the high school administration. Approximately one hundred Black students from two secondary schools gathered at the Gregory Congregational Church to protest the punishment and other grievances. Since Gregory was the headquarters of the local resistance and affiliated with the UCC, CRJ involvement in the local was a natural connection. Black students demanded justice in cases where they believed they and their peers were punished unjustly and also wanted the implementation of an African American Studies curriculum and recognition of the birthday of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. The students called for a boycott of classes until their demands were met. The CRJ dispatched an organizer Ben Chavis to provide more experienced leadership to the students and local activists.

The student protesters and the Gregory Church became targets of local elected officials, police, and white supremacists. The paramilitary Rights of White People group initiated terrorist drive-by shootings at the Gregory Church directed at the student protesters. Given the increased violence in Wilmington, CRJ Executive Director Charles Cobb requested Shakur’s assistance in the North Carolina community. Shakur’s experience in armed self-defense since he was a teenager and leadership in training to collective security played a critical role for this Black community under siege. He enlisted other trained New Afrikan Security Force personnel under his leadership, including Chui Ferguson and Ibidun Sundiata, to instruct Wilmington residents in armed self-defense strategy and tactics. The New Afrikan security provided training for Wilmington Black residents to defend their lives and Gregory from terrorist attack.

Hostilities increased resulting in spontaneous violence in downtown Wilmington. Blacks defending Gregory shot and killed Harvey Cumber, an armed white man who penetrated a police barricade around the church. The unrest led to a National Guard occupation of Wilmington. Federal, state, and local authorities collaborated to charge Chavis and 9 other activists with conspiracy charges related to the uprising, eventually convicting the Wilmington 10 and sentencing them to a total of 282 years of incarceration. The Wilmington 10 would ultimately be released due to a determined international campaign and the exposure of misconduct in the prosecution utilizing perjured testimony.

Revolutionary Nationalist Building Solidarity Relationships

While Mutulu Shakur was a New Afrikan nationalist, anti-imperialism and international solidarity was a critical aspect of his political practice and beliefs. The internationalism of Malcolm X is well documented. Malcolm encouraged Black people to support struggles of oppressed people in Africa, Asia, and the Americas. Particularly after leaving the Nation of Islam, Malcolm also began to develop political relationship with radical whites in opposition to capitalism and imperialism. Shakur’s political orientation from his “ideological father” Herman Ferguson, Gaidi and Imari Obadele and other Malcolm X associates and PGRNA founders certainly contributed to his internationalism. In a 1979 speech in solidarity with the Zimbabwe national liberation struggle against white settler colonialism, Shakur defined himself as a part of the “revolutionary nationalist anti-imperialist movement. His comrade Yuri Kochiyama described Shakur, “[He] was so internationalist. He was Black nationalist, a revolutionary Black nationalist, but he very international in every way. The insurgent nationalism of Shakur was not racialist and guided him to worked with comrades of a variety of ethnicities and nationalities for the liberation of New Afrika and human rights of all oppressed people against capitalism and imperialism. While he was a nationalist fighting for the liberation of the Black nation, much of his activism around fighting political repression, people’s medicine, and support for African liberation were collaborations with activists outside of the Black community. Shakur won allies for the New Afrika national liberation struggle from his practice and ideological advocacy.

Shakur’s relationship with Kochiyama illustrates his internationalist politics and practice. An associate of Malcolm X, Kochiyama was widely respected in the Black community. Her relationship with Malcolm X and citizenship in the Republic of New Afrika was unique. Through Kochiyama, Shakur reached out to activist Asian Americans for solidarity with the New Afrikan Independence Movement.

Japanese-American activist and singer Nobuko Miyamoto notes how she and other radical Asians participated in a PGRNA rally at the United Nations 1973 in her biography Not Yo’ Butterfly (2020). The rally called for a UN supervised plebiscite and the freedom of RNA political prisoners. Miyamoto and her musical partner Chris Iijima performed at the rally expressing their solidarity with the New Afrikan movement and situating the plight of Asian Americans with Third World national liberation movements. She notes how this performance grew greater bonds of solidarity between activist Asian and New Afrikan communities. Miyamoto, Iijima, and William “Charlie” Chin would also record an album titled A Grain of Sand, considered by some “the first album of Asian-American music.” A Grain of Sand featured a song dedicated to the New Afrikan Independence Movement titled, “Free the Land.” Mutulu Shakur and his (step) son Tupac were present at the recording of “Free the Land” and sung background on the recording Tatsu Hirano, one of his Asian American acupuncture students, developed a solidarity relationship to New Afrikan independence. Hirano stated, “For ex-slaves in this country to gain strength, to have self-determination. You need to have selfreliance. You need to have independence … . the Republic of New Afrika was the vehicle for that.

Yuri Kochiyama commented on how Shakur also exhibited support and developed relationships with Asian-American revolutionary organizations like I Wor Kuen (based in New York’s China town) and East Wind, a revolutionary nationalist and Marxist-Leninist collective of Japanese Americans in California. Kochiyama offered, “he supported and knew so much about Asia and the struggles of people of Asia …” She also acknowledged Shakur committing PGRNA workers to do security for an event in solidarity for the People’s Republic of China to be represented in the United Nations in 1971. He also assisted in organizing solidarity events for the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (aka North Korea)

His participation in the Lincoln Peoples Program and people’s detoxification program also included significant relationships with not only the Puerto Rican comrades, including members of the Young Lords Party, but also with radical whites. His work at Lincoln Detox demonstrates how Shakur collaborated with a cadre of activist white physicians at the Lincoln Detox Program, like Richard Taft and Barbara Zeller, and other white grassroots health care advocates and activists. Dr. Zeller’s medical credentials enabled the acupuncture treatment to function at Lincoln in a critical moment. She noted that Shakur and others initially worked with her but did not allow her to immediately join the Lincoln collective given the arrogant and oppressive relationship white physicians had with communities of color. Zeller’s humility, commitment, revolutionary posture, and service to Black and Brown patients and acupuncture students was critical in building a professional and political relationship with Shakur and the New Afrikan and Puerto Rican members of the collective Zeller later became a founding member of the May 19th Communist Organization.

Shakur’s relationship with the May 19th Communist Organization is an example of his cultivating political relationships with white anti-imperialists. His work against repression and at Lincoln Detox had an impact on the solidarity with white anti-imperialists who founded the May 19th Communist Organization. Commonly referred to as May 19th, May 19th Communist Organization was a Marxist-Leninist collective of white anti-imperialists whose primary work was solidarity with national liberation movements inside and outside the United States. The date May 19 is distinguished among revolutionaries by the birthdays of Vietnamese communist and patriot Ho Chi Minh (1890) and Black revolutionary Malcolm X (1925), and the death of Cuban independence fighter Jose Marti (1895)

May 19th had its roots in the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and the support network of the Weather Underground. National discourse intensified within the white anti-imperialists with the publication of Weather Underground’s book Prairie Fire: The Politics of Revolutionary Anti-Imperialism. The Prairie Fire Organizing Committee (PFOC) was organized to provide an aboveground, organizing vehicle and political program to make the politics in the publication a reality. The Weather Underground, through PFOC, utilized the publication to organize its network for the 1976 Hard Times Conference in Chicago, ostensibly to promote unified resistance during the economic recession of the period. The conference resulted in ideological struggle and political conflict, not a coordinated anti-capitalist and imperialist program of action and resistance. In the tradition of new left gatherings during the Black Power era, Black conference participants formed a caucus and placed demands on the Hard Times gathering organizers. Revolutionary nationalists and feminist activists were particularly critical of conference organizers goals of attempting to promote an objective of multi-national, Marxist-Leninist vanguard party to lead an anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist struggle within the U.S. empire. A primary motivation for the development May 19th grew out of the criticism by revolutionary nationalists and New Afrikan liberation forces that the Weather Underground’s Hard Times Conference did not recognize the vanguard role of the Black Liberation and other national liberation movements, inside and outside the borders of the U.S., in the fight to dismantle imperialism.

One of the recognized leaders and founders of May 19th was Italian national Silvia Baraldini. Born in Rome to a privileged Italian household, Baraldini came to the U.S. with her family when she was 14. She attended the University of Wisconsin at Madison, where she joined SDS and anti-war protests during the Vietnam conflict. After leaving college, Baraldini moved to New York and became active in defense efforts of the New York Panther 21 and captured Black Liberation Army members, including Assata Shakur. Shakur and other members of the NCDPP developed a working relationship with Baraldini in the work in support of the NY 21 and other revolutionary nationalist political prisoners. Her work particularly focused on building white solidarity with Black political prisoners.

Baraldini participated in and organized for the Hard Times and was responsible for recruiting Black liberation forces from the South, including PGRNA President Dara Abubakari, to the conference. The Weather Underground’s political positions and leadership of the conference disappointed her. She perceived the political direction of the conference leadership as an abandonment of the Black liberation movement, particularly the captive Black revolutionaries that had become the center of her political work.

Other key founders of May 19th were participants of work that Shakur was engaged in at Lincoln Detox. Shakur’s acupuncture student, Susan Rosenberg, also worked with him at Lincoln Detox, and participated in solidarity activities with the Black liberation movement. After the Hard Times experience, Baraldini and Rosenberg pursued a deeper understanding of the Black Liberation movement, even traveling to the southeastern U.S. to explore the potential and possibility of a New Afrikan national liberation struggle.

A recognized leader of the revolutionary nationalist movement in the New York area, Mutulu Shakur developed into a representation of the national liberation movement of the New Afrikan people for May 19th. Shakur consulted and collaborated with May 19th on its solidarity work with the Black liberation movement and freedom struggles on the African continent,

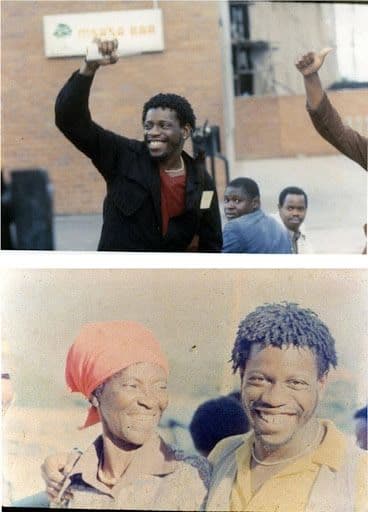

Dr. Mutulu Shakur in Zimbabwe in 1980 to observe the elections that ushered the country to Black majority rule.

particularly the fight against settler colonialism in Zimbabwe.

One of the best examples of his anti-imperialist work and collaboration with May 19th was their joint work in solidarity with the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU). ZANU was engaged in mass resistance and armed struggle of national liberation to dismantle white minority rule in their southern African country, called Rhodesia by the settler-colonial regime. The solidarity work included raising funds for material aid to ZANU. One of the most successful events was a 1978 benefit concert in Harlem to purchase an ambulance for ZANU. The concert featured popular artists including pianist and bandleader Eddie Palmieri, progressive singer and spoken word artist Gil Scott Heron, and Shakur’s friend Nobuko Miyamoto and Bennie Yee The following year, Mutulu Shakur delivered an address at Chitepo organized by a group led by May 19th cadre—the New York Material Aid Campaign for ZANU. A lifelong PanAfricanist, Shakur clearly linked the struggle against settler colonialism in Zimbabwe with the fight for Black liberation in the United States. Shakur traveled to Zimbabwe in 1980 as a part of a delegation to observe the independence elections in Zimbabwe for Black majority rule. The delegation included Muntu Matsimela of the Afrikan Peoples Party, former political prisoner Ahmed Obafemi of the PGRNA and Dr. Barbara Zeller of May 19th and was invited due to the solidarity work with ZANU in the fight against settler colonialism.

Underground and Clandestine Resistance

Mutulu Shakur went underground to avoid capture by the FBI/NYPD Joint Terrorist Task Force (JTTF) in March of 1982, after a Southern District of New York magistrate issued a warrant for his arrests along with former BPP member Jamal Joseph and his old PGRNA recruit Chui Ferguson. The FBI charged them with being part of a criminal enterprise under Racketeering Influenced Corrupt Organization (RICO) act. They argued that Shakur was part of a revolutionary collective called “the Family’’ a.k.a. “New Afrikan Freedom Fighters’’ that carried out a series of acts primarily directed against U.S. financial institutions. The federal prosecution argued that Shakur beginning in 1976 organized a clandestine unit that targeted armored cars and banks to secure funds to finance political causes and institutions, including the BAANA clinic, youth development programs, political mobilizations, and material aid for the fight against settler colonialism in Zimbabwe. The U.S. attorneys and FBI also included the 1979 escape of Assata Shakur from the Clinton Prison for Women as part of a criminal conspiracy.

Mutulu Shakur eluded the FBI and the JTTF for four years, ultimately being captured in 1986. The incident that sparked the manhunt for him and several former BPP, PGRNA, BLA, and white anti-imperialists was a failed attempt by the elements of BLA and its alliance with white anti-imperialists, the Revolutionary Armed Task Force (RATF) to take 1.6 million dollars from a Brink armored truck on October 20, 1981. On November 5, 1981, a BLA communique was issued to put the October 20 event in Rockland County into political context. The communique described the Rockland holdup as an “expropriation. Sundiata Acoli, an incarcerated BLA soldier defined expropriation as “(W)hen an oppressed person or political person moves to take back some of the wealth that’s been exploited from him or taken from them. The BLA communique stated the attempted expropriation was an action of RATF, a “strategic alliance … of “Black Freedom Fighters and North American (white) Anti-Imperialists … under the leadership of the Black Liberation Army … The RATF came together in response to an escalation of acts of white supremacist violence in the United States during the late 1970s and early 80’s, including the murders of Black children in Atlanta, Black women in Boston, the shooting of four Black women in Alabama, and the acceleration of paramilitary activity by the Ku Klux Klan and other white supremacist organizations

Shakur’s trial attorney, Chokwe Lumumba, argued he was not a criminal but a New Afrikan Freedom Fighter. While not claiming involvement in the activities he was charged with, his defense asserted these acts were not part of a criminal enterprise, but a result of the political conflict of the national liberation forces of the captive Afrikan people in the U.S. Under cross-examination, government’s witness Tyrone Rison, testified that the participants in these actions were “revolutionaries committed to the liberation of New Afrika, and that their deeds were designed to secure funds from the New Afrikan struggle, to maintain community service institutions for the oppressed black population, and to support other Afrikan liberation struggles in the world. Rison is a Vietnam-era veteran and a former worker in the PGRNA who became a prosecution witness and informant to avoid racketeering conspiracy, murder and bank robbery charges for himself and felony charges for his wife. He admitted on stand to killing the Brinks guard at a June 20, 1981, expropriation in the Bronx, NY. Despite admitting to the murder, Rison was rewarded with a 10-year sentence for his testimony betraying his former comrades and cooperation with the federal prosecution.

The prosecution’s case against Shakur was built by former movement activists, like Rison, who cooperated with the government’s case to receive lesser sentences. Prosecutors presented no incriminating physical evidence linking him to criminal offenses to the jury. Shakur and his codefendant Marilyn Buck were convicted on May 11, 1968, despite the prosecution’s lack of physical evidence and reliance on the testimony of compromised informants. Federal Judge Charles Haight ordered a 60 year sentence for Shakur and 80 years of incarceration for Buck.

Life in Incarceration: The Struggle Continues

Since his capture in 1986, Dr. Mutulu Shakur has been a political prisoner in several federal institutions across the U.S. He continued to engage in political education and consciousness raising of his fellow prisoners. Shakur established a “circle of consciousness” behind the walls at each institution he was incarcerated. The “circle of consciousness” would promote mutual respect for cultural diversity, political and cultural awareness, and intellectual and artistic development Several men incarcerated with Shakur credit him with promoting unity between a variety of elements in the institutions he was imprisoned, including street organizations like Crips, Bloods, Gangster Disciples, as well as religious and cultural communities as the Nation of Islam, Five Percenters, Sunni Muslims, Rastafarians, Christians, and a variety of other constituencies. This work is a continuation of the work he engaged in with Abubadika Carson to bring unity to street organizations in the city in the five boroughs of New York. Despite his work to bring unity and decrease violence inside some of the highest security prisons in the U.S., Shakur continues to be a target of political repression while incarcerated.

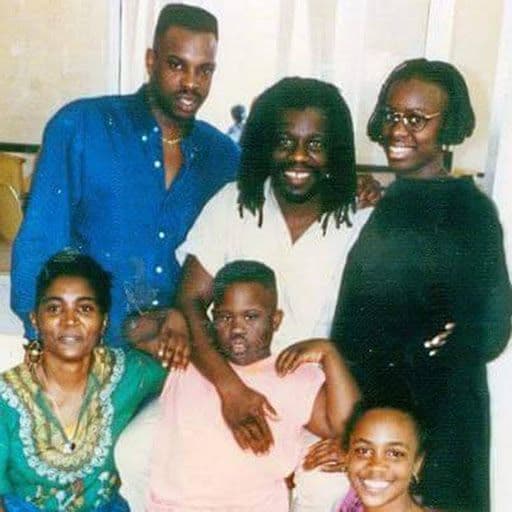

Incarceration did not prevent Shakur from being impactful inside the prison in the Black liberation struggle on the streets. His relationship with his (step) son and popular commercial Hip Hop artist and actor, Tupac Amaru Shakur, certainly aided his ability to organize inside the penitentiary. Dr. Shakur and other prominent individuals incarcerated around the U.S. conferred and decided to establish a code to discourage violence and informants and encourage order in Black and Brown communities. Vehicles to establish conflict resolution between street organizations were established. Tupac Shakur was asked to be the “face” of the code, which was titled the Thug Code. Dr. Shakur, Tupac and Mutulu’s son and HipHop artist Mopreme were signatures to the Thug Code, issued in 1992. Tupac worked with local activists and performed at grassroots gatherings in New York and New Jersey to promote the Thug Code Tupac also visited and brought other Hip-Hop artists, including fellow Thuglife and Outlawz artist Big Syke aka Mussolini (Tyruss Gerald Himes), Bay Area rapper and producer Mac Dre, and all-female Los Angeles R&B and Hip Hop group YNV to the Federal Correctional Institution (FCI) in Lompoc, California in 1993. Tupac’s performance at the federal prison inspired young prisoners across the U.S Dr. Shakur believed Tupac’s arrest for sexual assault and 1994 shooting outside Quad studios in New York was related to his advocacy of the Thug Code and a part of counterinsurgency to prevent the radicalizing of Black street forces

Dr. Shakur organized a memorial musical tribute project to salute Tupac, ten years after his untimely death in 1996. The project, Dare to Struggle (2006), included underground artists on the street and those incarcerated. Mutulu Shakur and Canadian music producer and artist and Hip-Hop activist Raoul Juneja (a.k.a Deejay Ra) served as executive producers on Dare to Struggle. Artists on the project included Dr. Shakur’s children Mopreme and Nzinga, Tupac’s group the Outlawz, and those affiliated with the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement, Ife Jie and Zayd Malik, and an Iranian M.C. Imman Faith. Incarcerated artists like Strap and the group SCU (Solitary Confinement Unit) also joined the project. One of the artists who contributed a song that didn’t make the album was a young rapper from L.A. named Concept, who eventually became an internationally known Hip Hop performer and entrepreneur, Nipsey Hussle

Dr. Shakur proposed programming and education focused on Hip Hop to make Cultural Diversity classes sponsored by Georgia State University’s (GSU) African American Studies in United States Penitentiary (USP) Atlanta. Shakur’s proposal was offered to promote more participation among younger prisoners in the Cultural Diversity classes. The proposal centered around a Hip Hop Summit that included engaging prisoners with scholars from GSU, Morehouse College, and the University of Georgia and participation from members of the entertainment industry, including popular radio deejay Greg Street from Atlanta’s V103 FM and Disturbing the Peace Records. The Hip Hop Summit was transplanted to the Federal Correctional Center (FCC) at Coleman, Florida in 2005. FCC Coleman is the largest federal correctional center in the United States with two maximum and a medium and minimum-security facility for men and a prison for women. Warden Carlisle Holder was the chief administrator for three of the facilities (one maximum, the medium, and women’s prison). Holder encouraged education and rehabilitation and there were few incidents of violence in the facilities under his command. Shakur worked with other prisoners and friends from the community to organize cultural and educational programs at FCC Coleman. The Hip Hop Summit and African American History Month drew significant participation from prisoners and included outside guests including Hip Hop artist Ja Rule, former Black Panther, writer, and theatrical producer and director Jamal Joseph, New Afrikan activist Ahmed Obafemi, African-centered scholar Marimba Ani, and music mogul Chazz Williams (the cousin of Shakur).

Continued Political Repression While Incarcerated

The federal Bureau of Prisons used a leak of an unauthorized video recording of programming at USP Coleman as a pretext to investigate Shakur ultimately transferring him to USP Administrative Maximum Security (ADX Florence) in Florence, Colorado in 2007. ADX Florence is the highest-level security facility in the federal prison system. The transfer of Shakur and other prisoners, as well as USP Coleman staff, effectively disrupted the educational and rehabilitation activities at the institution and discouraged other federal prisons from instituting similar programs.

Dr. Shakur was transferred from ADX Florence (in Colorado) to another maximum-security facility USP Victorville in California in 2011. The political repression of Shakur continued as he was placed in segregation there after an officer monitoring his February 2013 phone call to a Black History Month program at California State University at Northridge determined he was “inciting a riot,” a peculiar assessment since he was speaking on the need for a truth and reconciliation process in the United States to the event (which included actor Danny Glover) He suffered a stroke while in isolation, most likely since in segregation, Shakur was prevented from access to the food and exercise he utilized to manage hypertension.