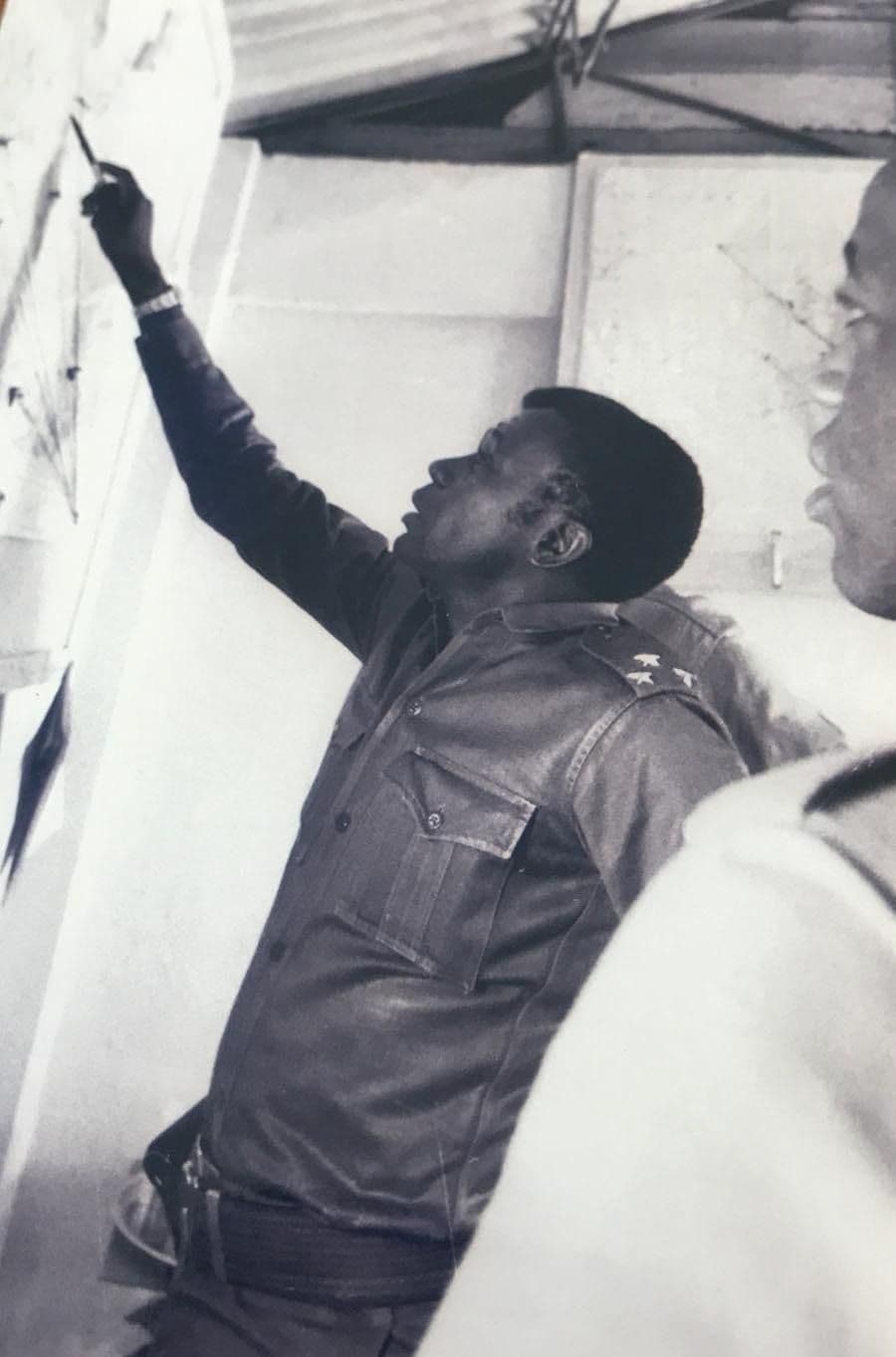

Victor Emilo Dreke Cruz is a walking archive. Today, at age 82, his life represents the arch of the Cuban Revolution. He was fifteen in 1952, when General Batista waged a military coup in order to protect US economic and Cuban elite interests. It was at this moment that Dreke joined the resistance. First as an organizer, then in charge of a sabotage unit, and then as leader of campaigns against the dictator’s police and army. Once the revolution succeeded, he took leadership in the Armed Forces. He battled counter-revolutionary forces at the Bay of Pigs, in the Escambray Mountains and served with Che Guevara in the Congo after the assassination of Patrice Lumumba. He worked with the brilliant theorist Amilcar Cabral in Guinea Bissau and Cape Verde, and trained many leaders from the global south in Cuba (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Victor Dreke, Havana, December 2019.

This essay examines the class, racial, regional, and neo-colonial context of Dreke’s upbringing which forged his undaunting commitment to the Cuban revolution. It also details the central role he played in propelling Cuba’s internationalist vision of “solidarity as foreign policy.” The Congo (1965), as mentioned above, was Cuba’s first major military mission in Africa and Dreke was there as second in command to Che Guevara; and it was there that he was given his underground name, Moja. Dreke recalls with humor that Che used a Swahili dictionary to name each member of the mission and not wanting it to be too complicated, all noms de guerre were numbers, causing locals to wonder who these men were with numbers for names. Moja is number one in Swahili. Che was Tatu, number three.

When I asked Dreke, if I could classify him as a five-star general, of which he is an equivalent, he emphatically said: “no.” He argued (with me) that the Cuban military leaders chose instead to call themselves comandante, or commander as it was more egalitarian and because historically generals had been the henchmen of brutality on the Island.

Dreke graciously allowed me to interview him numerous times between 2015 and 2019. Neither these interviews nor this article would have been likely nor possible without the labor and patient solidarity of the following: Otis Cunningham, Dra. Ana Morales, Dra. Lucila Insua, Humberto Scasso, Rita Olga Martinez, Adelina Hilton, Zuleica Romay, Gloria Rolando, Raul Dias, Olympia Men,endez, the Arcus Center for Social Justice Leadership at Kalamazoo College, and the Center for Art, Design and Social Research (Boston/Helsinki).

On language: I have chosen to use “Black” to designate all of those in Cuba who are of phenotypical African descent. Use of the term “mulatto” remains a descriptive term used by the state and by many Cubans in regular conversation. “People of Color” was common as a descriptor as well in the past. However, those engaged in anti-racist struggles in Cuba often use “negro” or black to describe themselves and this is especially the case among those who see themselves as Black Cuban revolutionaries today.

Victor Emilio Dreke Cruz was born on March 10, 1937 in the bustling town of Sagua la Grande, on the north central Atlantic Coast of Cuba, in the then province of Las Villas. He was the youngest of eight brothers who lived in a house with a dirt floor and a roof, that he called “primitive.” His mother, who had been a house maid, died when he was one or two years old, and so, he was raised lovingly by his father, an aunt and his step mother.1 In fact, he says that he is very proud to have had three mothers, and maybe a fourth, the revolution.2

His father, Bruno Dreke Castillo, like many Cubans, pursued numerous vocations to make ends meet. Dreke Castillo was a musician, a carpenter and sold fish at a local market. According to Victor Dreke, his father had little faith in Cuban governance or its politicians of the time, telling him that none were good, especially for blacks. Nonetheless, Dreke’s father “sold his voting card”3 to the Liberal Party in Cuba’s robust and inescapable system of pay-to-play politics in order to pursue his trades, visit the doctor and support his children.4 He was literate and a political sergeant for the Liberal Party to whom many community members came for advice.5 Even so, according to Dreke, “we often got up at 4:00am as children to go with him to the market to sell his goods.” “Sometimes he could not pay the taxes and we were kicked out,” says Dreke. Even with his ties to the Liberal Party, Dreke says, “we suffered so much; the main characteristic of the Cuban people was poverty, but if you add black to that, it was a special kind of poverty.”6

There were two major parties in the early 1940s, along with a host of shorterlived ones. The Liberal Party and the Conservative Party both date to the founding of the Cuban republic and like their Democratic and Republican counterparts in the United States, they played both inclusive and duplicitous roles viz-a-viz black people in their nations. Yet, there were key differences between political party formation in Cuba and their equivalents in the United States. First, Black men in Cuba were able to vote from the (1902) founding of their republic. The Cuban constitution had this codified and thus needed no amendment like the 15th in the U.S. This was probably due to the fact that the black population hovered at about 50% at that time, driving all of Cuba’s mainstream parties to court them.7 Black people had also been leaders in the fight for independence from Spain; and, had their constitution not included them, there would have likely been major political upheaval. Second, there were black men elected to the earliest national legislative bodies, even though numbers never equaled their demographic weight. For example, in 1904, 4 out of 63 representatives were males of color; then in 1908, 13-15 percent of the Cuban Congress were black and mulatto.8 Between 19401959, there were actually numerous political parties and black Cubans were represented, to some extent, in all of them.

Sagua la Grande, where Victor was born and where he credits his early ideological growth, was originally established by the Taino people. It sits on a peninsula next to the Sagua la Grande river, whose mouth opens up into the Atlantic; it has always been perfectly located for trade. With Spanish colonial and then US neo-colonial domination, the town emerged into an industrial and commercial powerhouse. Its Isabela harbor was a major trading port for all Cuban exports and imports to and from the US, Europe, and Latin America.

In the 1940s, Sagua la Grande had 47 sugar centrales (millworks) and was a hub of impressive and highly developed industrial complexes: the MacFarlane smelter, the electrochemical plant, the Infierno Distillery, and the railway workshops.9 Together these represented a highly functioning sugar mill complex, displaying in the words of Fernando Ortiz in his seminal work, Cuban Counterpoint: Tobacco and Sugar, “a system of land, machinery, transportation, technicians, workers, capital and people who produce sugar. It is a social organism, as alive and complex as a city or municipality.”10 These works in Sagua la Grande were considered at the time to be the largest and most advanced multiplex of its kind in Latin America and the Caribbean.11

Las Villas, now Villa Clara, the province in which Sagua la Grande is located has been pivotal to all of the Island’s revolutionary and economic thrusts. According to historian Gillian McGillivray: “When Cuba’s Third War of Independence started in 1895, the center of the Island, particularly Las Villas became a highly contested region. It was strategically important because it produced 40 per cent of the Island’s sugar and it lay between the revolutionary East and the Spanish-loyalist West.”12

In fact, on October 30, 1895, Antonio Maceo, the black revolutionary general wrote, “I am on my way to Las Villas province leading the invading army. The troops’ spirit is excellent.”13 The Spanish colonial forces also understood the strategic importance of the region and concentrated their forces there. But when Maceo’s seventeen hundred anti-colonial troops captured Las Villas, he stated to the people there: “Our mission is a high, generous and revolutionary one. We want the liberty of Cuba. We long for peace and the future well-being of all our children.”14

Las Villas represented an ideological sharp-edge between East and West, black and white, industrial workers and mill owners, and rural labor, colonos (independent farmers) and latifundia (big landed estates). Maceo’s special dictum to the people of Las Villas was likely intended to allay tensions that had long simmered in the area. Fear of black military and working-class leadership had undermined the first war of independence, twenty years earlier. Most historians agree that war, known as the Ten Years War (1868-1878), was largely lost because of internal conflict exemplified by Las Villas.15

As a younger Maceo and other officers were making their westward march toward Las Villas during the Ten Years War, many of the white revolutionary officers met in Las Tunas, a province just east of Las Villas to stop the procession. These officers, representing a white creole elite, refused to support the Western advance, arguing that the people of Las Villas wanted their own regional autonomy. Known as the Sedition de Lagunas de Varona of 1875, it opened up the way for the Pact of Zanjon with Spain which ended the war in 1878. This was done against the wishes of Maceo and without the immediate end to colonial rule or enslavement. Maceo and others continued to fight in what became known as the Second War of Independence or the Little War (1878-1879). Yet, without armaments and the funds of the white creole elite, it officially ended a year later.

Race and class contradictions continued to plague the independence forces during the Third War of Independence as Maceo is killed in battle in 1896, Spain is defeated in 1898 and the United States intervenes and occupies the Island that same year. When decorated black general Quintin Bandera was court marshaled for what appeared to be minor offenses in 1897, he stated: “I foresaw what would happen to me, for in Las Villas the Jefes (officers), in their majority, did not want to be commanded by officers of color.”16

Bandera continued to speak out as the Republic came into being in 1902. A 1906 New York Times article noted that Bandera “had been the first man who crossed the Spanish trocha which shut off the province of Pinar del Rio from Havana province”17 during the 1895 War of Independence and “that he was well known in every province of Cuba.”18 And yet, the only job the government saw fit to give him after the War was as a “door keeper of the House of Parliament.”19 In fact, “blacks and mulattoes had made up the larger part of the liberation armies in the independence wars against imperial Spain.”20 Dreke makes note of this in a 2002 Atlantic Constitution article, where he credits “Cubans of African descent with the start of Cuba’s independence movement.”21

Bandera must have felt a profound sense of betrayal. By 1919 Blacks only made up 12% of the republican army.22 Bandera’s analysis was correct when “he was in the habit of gathering crowds of negroes about him and making speeches to them on the ingratitude of the Republic.”23 The 1906 New York Times piece mentioned above was actually written on the occasion of his murder. Entitled, “The Killing of Bandera: Negro General and Two Companions Shot and Slashed to Death,” it describes how Bandera was hunted down and killed by Cuba’s Rural Guards on August 23rd 1906. The Rural Guards were racially segregated and commanded by white United States forces.24

Victor Dreke was born five years after the 1932 creation of the National Sugar Workers Union and just four years after the over throw of Dictator Gerardo Machado by a massive left-leaning coalition led by Professor Ramo,n Grau San Martin in what was called the Revolution of 1933.25 He was eleven years old when the larger than life Black Communist leader of the Sugar Workers Union, and former congressmen, Jesus Menendez, known as the “General of the Cane” was assassinated. Menendez was also from Santa Clara, the largest municipality of the province of Las Villas. On Victor’s 15th birthday, March 10, 1952, General Fulgencio Batista y Zald,ıvar staged a military coup “on the eve of an election, he had run for and could not win.”26 Batista had been a strong man for years, and had been in politics either through election or coups since 1934. By 1952, he was primarily known as Cuba’s leading comprador of torture and assassination of resistance leaders, like Menendez.

Dreke, like all in his generation in Cuba, was born into a highly politicized nation that for the most part never accepted its neo-colonial status nor its United States-controlled extractive economy. Between 1902-1952, there were at least five rebellions, four coups, two revolutions, numerous political parties, the growth of a strong largely black communist party and scores of regional and national strikes.27 Workers’ actions were so persistent in the 1940s that the New York Times reported widely on their activities. Here is a list of just some of the headlines from the 1940s: “Sugar Workers Strike; Cuban Conflict May Tie up Grinding Operations on Island,” New York Times, January 14, 1941; “Cuban Sugar Workers Strike,” New York Times, November 3, 1941; “Strikes Spread in Cuba, and Sugar Mill Workers Quit–Railwaymen Call Halt,” New York Times, April 16, 1943; “Sugar Pay Rise Asked: Cuban Workers Want 20% for Industry in Cuba,” New York Times, January 19, 1945. Importantly, according to Jorge Ibarra, communists were most active in unions in Oriente and Las Villas.28

The fight was tense and workers’ unity so strong that Jesus Menendez and the union accountant traveled to Washington D.C in October of 1945 and “force[d] their way into trade negotiations”29 on Cuba’s sugar quotas, price guarantees and compensation viz a viz the US. Although, not invited, and no agreement was reached, their intellectual and political heft was registered. In 1946, the US Secretary of Agriculture, nervous about strikes and sugar shipments, traveled to Cuba and negotiated a contract with the union and the Association of Mill Owners. This was an unprecedented compact between an advanced capitalist state and a small underdeveloped nation. In 1947, sugar workers were making 40% more in pay than they did in 1946.30

Menendez was assassinated just two years after the agreement. His murder reveals deep plots by US and Cuban sugar interests to halt the gains made by the poor and working class of Cuba.31

For young Dreke, the fight was just beginning. He remembers the 1952 coup his birthday as the moment he entered the liberation struggle. Although only 15, he, along with about ten other teenagers staged what was the first of many youthled actions in Sagua la Grande. He wrote: “we were a rebellious bunch but we didn’t know the first thing about revolution.”32 He remembers being arrested that day, but because he was so little and scrawny, the police, he said, felt sorry for him, and let him go. He was not to be so lucky as time went on.

Dreke had gone to primary school at great sacrifice to his father, who had to pay for school and then he went to Jose Marti High School. It was while there that he became a student leader and began organizing students between the ages of 15-18. Because Sagua was an industrial center, the students quickly attached themselves to and became the youth bloc of Regional Workers Federation #3 in Sagua la Grande. According to Dreke, it was the workers of the town “who were the main revolutionaries”33 and the students joined them. He is proud of the unity created between the student and workers movements and says that he is the ideological product of this combination, this symbiosis.34

Among the first actions of the young students were to pay public homage to those that they viewed as martyrs. Dreke remembers doing so in honor of Antonio Maceo, Jesus Menendez and Antonio Guiteras. Guiteras had been the Minister of Interior during the 1933 revolution. Under the Guiteras leadership, the government nationalized many sectors of the economy, especially those owned by US capital such as the national telephone company. That revolution was overturned by Batista’s first coup and Guiteras was assassinated on May 8, 1935. On May 8th for the next few years, the student movement publicly memorialized him.

The police and military in Sagua came to know the youth sector of the Regional Workers Federation #3, so much so that they were often picked up on any key day such as March 10th or May 8th, before they could fully carry-out an action. If they did manage to pull off a protest, “they were lighting [quick] events.”35 Dreke says that he was once asked by a local policeman why he continued to cause political trouble. Increasingly, he said, because he was a revolutionary. This policeman, known as Jova told him: “who ever heard of a black Cuban revolutionary? Blacks are chicken thieves.”36

On July 26, 1953, a twenty-seven-year-old attorney named Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz, organized a raid on the Moncada Garrison in Santiago de Cuba in the eastern province of Oriente. The Moncada was the second largest military complex on the Island. His goal, to unleash a revolution. Unfortunately, Fidel’s band of over one hundred men and women were outnumbered, got trapped, and many were tortured and killed. Those raiders who survived were put on trial as were those believed to have provided intelligence and/or logistical support.37 Many radical leaders at the time, especially those in the communist party, did not back the attack; they viewed it as suicidal and voyeuristic. Nonetheless, Fidel, who was arrested used his October 16, 1953 trial like Nelson Mandela did ten years later as a political platform. As the trial began and he was permitted to speak, he gave a four-hour speech explaining the condition of a majority of the Cuban people, which ended with the now famous text History will absolve me. He and his brother, Raul, were sentenced to fifteen and thirteen years in prison, respectively. Yet, Fidel’s eloquence, the popular struggle of the Cuban people, and the international attention led to the sentences of Fidel, Raul and other rebels to be commuted on May 16, 1955. The rebels immediately went to Mexico to re-group.

Dreke writes of the Moncada attack: “July 26th 1953 was a Sunday. We didn’t know anything about the events of that day. But at dawn the following day, the police came and arrested us, and took us to the police station.”38 It was at the station that they learned of the raid. Dreke recalls: “From that moment, I identified my new leader; it was Fidel Castro. He had done what Antonio Guiteras had tried, and wanted to do.”39 “The courageous deed by Fidel inspired optimism and led [us] to admire and respect him. A path was opened up,” Dreke writes.40 Of course, Fidel’s action led to many debates in Cuba on the efficacy of armed struggle, and Dreke remembers those debates. It was during that time that he decided to committ himself to armed struggle.

The July 26th Movement, coined after the day of the Moncada attack, was officially formed in 1955. Victor and most of his Sagua confidants joined immediately. Now aged 18, Victor became head of sabotage for the July 26th Sagua cell. During the first phase, their work was primarily aimed at popular mobilization and mass actions – such as strikes, demonstrations, torching cane fields, etc. and psychologically destabilizing the powers that be. With humor and humility, Dreke shared three sabotage stories with me.

His first story: they decided to disrupt electricity in the city, to show their strength and to attack an utility owned by US interests. According to a US Department of Commerce Survey, published in 1956, US interests, “owned 90 per cent of telephone and electric services.”41 Dreke’s rebels did this by throwing heavy chains over the electrical wires and then tugging on them to pull the wires down, forcing an outage. They also set off small bombs, usually not big enough to cause much damage, but they were placed in areas to roust, frighten, and/or distract the police. He says they worked very hard to avoid civilian causalities.42 Finally, they wanted to taunt the police with the notion that the revolution was coming. They did this by surreptitiously placing the July 26th movement flag in unlikely and surprising places, such as the top of a sugar mill. Victor laughs when he tells of this third tactic. He says that one day they captured birds by placing food in cages. Once the birds were caught, they attached a string with a July 26th Movement Flag to each bird and then set them free. As the birds flew around the city, the entire people would see the flag. This infuriated the police but inspired the people.43

On December 2, 1956, Fidel and his rebels returned to Santiago de Cuba from Mexico crowded onto a yacht they called Granma. Again, they were ambushed by Batista’s army upon landing. Many were killed and some held for trial, only a small number fled to the nearby Sierra Maestra mountains to set up a guerilla base.

It is important to note that while historians have tended to center the guerillas with Fidel in the Sierra, there were many resistance cells, as seen in Sagua, that have received much less attention. One of the most significant was the urban underground, known as the llano, led by Frank Pais, Vice President of the Federation of University Students and founder of the Oriente Revolutionary Action (ARO). Importantly, Pais had planned to link the landing of the Gramna with a Santiago uprising, but the boat’s arrival was late and the uprising was aborted. Nonetheless, Pais was arrested and put on trial with those caught from the Granma. Once released, the llano did coordinate with the Sierra during the early months of 1957 by providing much needed food, medicine, weapons, equipment, clothing and serving as a laison for news outlets interested in meeting the bearded ones in the mountains.44 On July 30, 1957, Frank Pais was assassinated in the street by the Batista’s henchmen. He was 33 years old.

By December of 1957, the struggle had intensified. In Sagua, Victor, now twenty years of age, and his comrades were engaged in a major revolutionary offensive. Thousands of people were in the streets, sugar cane fields were burning, and workers were on strike. Two of Dreke’s comrades were picked up by police. He heard that they had been tortured, and tht they had unfortunately talked. Dreke, too, was now being hunted. It was decided that he should go into hiding. He went to the neighborhood he grew up in, Pueblo Nuevo. With the help of cousins, and friends who owned a furniture store, he managed to escape.

He shared his escape story in which a ruse was fabricated. His cousins a man and wife purposely had a loud conversation about the fact that they were expecting new furniture. Everyone on the block heard their discussion and wondered what was going on. The next day the furniture was delivered and taken in the house. When the wife returned home that evening, she squawked that she hated the furniture, her family could not afford it and it all had to go back. With fanfare, they re-loaded the truck with the furniture. Unknown to the police, who were patrolling the streets, Victor, because he was of small stature, was hidden in a dresser. Members of the July 26th movement managed to get him to Santa Clara.45 Victor Dreke, now in hiding, was determined to join those engaged in armed struggle. With the help of compan~eros, he made his way to the Sierra Escambray, the mountain range in Las Villas. There he joined a group of fighters that had emerged out of the student movement called the March 13 Revolutionary Directorate.46 Victor was excited by them, because like him, they were students. He quickly showed his bravery and military prowess and became involved in making strategic decisions and developing tactical maneuvers. Their goal: to engage the Batista forces, both army and police, with sabotage and guerilla activity, to cause economic damage to key enterprises, to inspire people to rise up, and to liberate cities, towns, and rural villages.

He was very excited by the taking of Sagua on April 9, 1958 by workers during a national strike. Although, he was not there, he noted that a dockworker and a sugar worker led that rising and held the city for 72 hours. Both were killed by the Batista forces.47 This, he said, led to further outrage and revolt. Victor is proud to say that Sagua was the first city to be liberated for a time.

The province of Las Villas proved to be just as important to this revolution as it had been nearly 100 years before. While the first Front was in the Oriente province of the East, where Fidel and his rebel army had been active throughout 1957,48 another front opened up later that year in Las Villas, under the direction of the March 13 Revolutionary Directorate of which Dreke was a leader. A special to the New York Times published on January 28, 1958 announced as much: “Cuban Rebels open a ‘Second Front:’ Youthful Insurgents Raid Military Post in South Coast Mountain Area.” The author, R. Hart Phillips goes on to write that this second front was based in the mountains of Las Villas and was made up of two hundred youths belonging to the Revolutionary Directorate.49 This second front continued to operate throughout 1958 and by the end of year, another R. Hart Phillips piece stated that; “fierce fighting between Cuban Government and Rebel forces in Las Villas Province continued today. The insurgents claimed the capture of 80% per cent of the province.”50

During 1958, just like in the previous revolutionary wars, multiple columns made simultaneous western advances toward Havana. And similar to before, Dreke notes that a huge number of Batista forces were deployed in Santa Clara, the primary municipality of the region, in an attempt to stop them. In fact, Santa Clara was the third largest military district in the county by this time, after Havana and Santiago de Cuba. Batista did this also because the second front was deepening its position in a good number of villages and towns in Las Villas. Importantly, the war was similar in another way as well. Just like before, it included a large number “of the country’s intellectuals, businessmen and professional men”51 and women, with all the racial and class cleavages.

During 1958, Dreke was involved in many key missions in Las Villas. He shared three important ones with me which had to do with the final months of the revolutionary war.

One occurred on October 13, 1958. Dr. Ernesto Che Guevara and Camilo Cienfuegos, two key July 26th leaders from the Sierra Maestra, were leading their troops west. They were hoping to get through Las Villas toward Pinar de Rio, the only province west of Havana. In order to assist their advance, the Revolutionary Directorate launched two distraction missions aimed at pulling forces toward them and away from the columns. They decided to first stage actions in two cities, Placetas and Fomento. In Fomento, the rebels took over a radio station and issued a revolutionary statement. In Placetas they planned to attack a police station. Dreke recalls that it was pouring down rain when they got to Placetas. Just as they were approaching the police station a car shined its lights on them, blinding them in the rain. When Dreke got out and ordered the car to stop and asked who they were, they said, “the police,” and the police then asked, “who are you?” Dreke’s band responded by saying: “the Directorate,” and a shoot-out occurred. During the melee, Dreke was hit by two bullets, one in the leg and the other in the side, just missing his lungs. He managed to get out of there and received quick medical assistance.

Two months later on December 17, 1958, another engagement occurred, when a fighter from their unit, Joaquin Milanes, known as “the Magnificent”52 went on trial. Nicknames in Cuba were common, especially among blacks and the working classes, and this practice moved easily into one’s nom de guerre. The “Magnificent” was arrested for carrying a firearm without a license. The authorities initially did not know his true political identity; but by the date of the trial, they did. He was the rebel who had attacked Santiago Rey, the Minister of Interior, a few months earlier. The Revolutionary Directorate feared that he would be sent to the death squads and so they planned a rescue mission.

Dreke tells a dramatic story of this operation. The rebels arrived early in the morning, planning to take their comrade immediately. Yet, because of the situation at the Courthouse, they decided to wait. They had a machine gun, a few revolvers and were nervous. Because the courthouse had three floors, two comrades hid their revolvers, and went into the building. Of course, this is before metal detectors and electronic surveillance and thus possible. Dreke stayed in the car with the machine gun on his lap. Sitting there, he noticed small assemblage of heavily armed civilians sitting in cars. He realized that they were members of a well-known death squad called the Masferrer Tigers. Rolando Masferrer was a wealthy politician who deployed these men all over the country. As Dreke recalls, “can you imagine, me there with a machine gun on my lap, and the death squad right near me?”53

Milanes was convicted of attacking the minister. As he was being escorted out of the courthouse, it was clear that he was to be handed over to the Tigers. The two combatants who had been inside the court house came out and went into action, shooting the police escorts. Milanes then grabbed the guns of the downed officers and a shoot-out occurred. One of Dreke’s men was hit. Yet they got him and the other rebels in the car and sped to safety. They stopped along the way to get a doctor’s help. The doctor they found was willing to help but told them that the official story had to be that he was kidnaped so that should it be discovered that he had helped the rebels, he would not be punished. The doctor did help, yet, Dreke’s comrade died.

The fourth and final mission was decisive. It was the taking of Santa Clara. The Revolutionary Directorate and the July 26th forces led by Che Guevara and Camilo Cienfuegos were now working in complete tandem and they had two targets: an army military train and a highly fortified military complex known as Squadron 31 that sat on a central plaza in Santa Clara.

They launched their campaigns on December 28, 1958. Squadron 31 had tanks but the rebels had people who hid them and poured into the streets with Molotov cocktails. On Day two, Che and Camilo’s forces succeeded in capturing the army train, thus enabling them to send weapons to Santa Clara. That same day, the Associated Press reported: “The bitter and bloody Cuban revolution was at a critical peak tonight. Rebels battled government troops in streets and houses of Santa Clara in a bid to cut off Havana from the rich southeast sugar provinces. … Three rebel columns pushed in Santa Clara after an encircling maneuver. … The rebels’ strength was not immediately determined but it could run to 3,000 or more. … Bodies were reported to litter the streets in Santa Clara.”54 On Day four, December 31, 1958, with Dreke as second in command, Batista’s men raised the white flag in Squadron 31. As Dreke entered the building to take control of the Squadron, he learned that Batista had boarded a plane to the Dominican Republic and the army was downing its weapons throughout the country. They had won!

On January 1, 1959, the triumphant rebel forces marched from Santiago across the Island into Havana with millions of people ready to make a revolution. As one can imagine, there were massive tasks ahead of the young revolutionaries and there was considerable confusion in major pockets of the country. The leaders of the revolution got to work immediately on two things: one, making sweeping legal, economic and social changes which benefited the poor and working people, and two, creating a military and voluntary militia structure to defend these efforts. Both of these worked together to create consciousness and inspire support for the revolution.

Logically, Victor Dreke was assigned to the second of these endeavors. He became battalion chief of the Western Tactical Force and on May 29, 1959 set out by foot with a large group of revolutionaries from Havana to Pinar del Rio. The goal was to see who were physically and emotionally ready to be soldiers, and to train some and weed out others. That Force was then divided into three armies: The Western, the Eastern and the Central (Figure 2).

Dreke was then assigned as Squadron chief in Las Villas, where not surprisingly, Cuba’s contradictions were playing out. He was first sent to Sagua, his home city, where there were divisions surrounding the memory of the April 9th, 1958 uprising and the take-over mentioned earlier. He was then assigned to Cruces also in Las Villas where all hell had broken loose over the desegregation of a park. There had been a celebration of the revolution in a local park and the military leader of the town had removed a rope traditionally strung to separate black from white. This was something some whites resisted.

Figure 2. Victor Dreke, Teaching Tactics, Ej,ecito Juvenil del Trabajo, (Youth Labor Army).

Parks and public spaces had always been key sites of class, race and gender contestation in Cuba, like in the United States. In colonial times, parks were places where young men and women “engaged in courtship rituals.”55 Ropes began appearing during the republican era (1902-1959) and were aimed at policing both gender and racial boundaries. As the revolution began to order their removal and to desegregate public spaces more broadly, many white Cubans felt that integration was being forced upon them. Alternately, for Afro-Cubans, it illustrated that the revolution was indeed on their side. Devyn Spence Benson quotes a 1959 Afro-Cuban interviewee in a local newspaper in Santa Clara: “The greatest conquest for the people of Santa Clara after the triumph of the revolution is the change that occurred in the everyday lives of the black race. In Santa Clara, the revolution is working intensely to achieve rapid integration. This began when they eliminated the bands of whites and blacks in the park.”56 By bands, he is referring to the ropes.

Anger at these changes was indeed a reason for white exodus after the revolution. Scholars and commentators often argue that the first wave of Cuban immigration was due largely to socialist policies implemented by the new regime. It is clear now that racism was also an impetus. In fact, the vast majority (over 90%) of the nearly 248,000 Cubans that moved to the United States between 1959-1963 were white and upper middle class.57 In addition, Little Havana, in Miami, set up by these early Cuban emigres have been noted for its racism.58

Dreke shared another intriguing story of his own city of Sagua. He said that when Fidel made his second visit to the United States in September of 1960, many revolutionaries were worried about his safety. After all, as shown above, the US had collaborated with Batista to kill many. Thus, Cubans were relieved when Fidel found support in Harlem, then known as the capital of Black America, especially after his meeting with Malcolm X. In an act of solidarity, Sagua’s barrio of Villa Alegre, which had a large concentration of black people, met in a park and declared that their neighborhood was to be renamed Harlem! In addition, four workers took Eliecer Jovar, the Cuban representative of the US company, the Miami Trade Agency, hostage.59 Jovar lived in the Hotel Sagua. They trapped him there, declaring that they would not release him until Fidel arrived home safely.

The people of Sagua had a right to be nervous, for the US was up to its old tricks again, trying to get a foothold in the Island. As early as January of 1960, a group of counter-revolutionaries, called ‘bandits’ by the Cubans, began operating first in Oriente60 and then in the very Escambray mountains where Dreke had worked only two years earlier. They were comprised of Batista supporters, large property owners, those desirous of becoming a new bourgeoisie, disgruntled revolutionaries, and criminals. They were funded and armed by the CIA.61 Their goal: to create havoc, undermine revolutionary programs, deplete resources, and possibly serve as a rear guard for future invasions.

Actually, one key target of Los Bandidos was young people of the Literacy Brigades who were being sent into remote areas to teach all Cubans to read. This was one of the many projects of the early revolution aimed at lifting up all Cubans quickly. On January 5, 1961 Conrado Benitez, an 18-year-old black brigadista from Santiago de Cuba was tortured and killed by counter-revolutionaries in the Escambray region – as were others. In November of that year another brigadista, 16-year-old Manuel Ascunce, was murdered along with the father of his host family, Pedro Lantigua.

But, like many of the mass projects of the revolution, attacks by bandits on peasants and literacy campaigners only served to strengthen revolutionary resolve. Nearly 200,000, mostly teenagers were instructors, most were urban and over 50% were gendered female. The nationwide effort functioned not only to teach people to read, but served to increase age parity and strengthen national unity among women and men and urban and rural communities.62 It also gave young women an independence hitherto unknown in Cuba.

In April of 1961, Victor Dreke was head of a military training school and the session had just ended. He was on his way to Santa Clara to get his next assignment. Upon entering the city, there was bedlam, and he heard that there had been an invasion in the small swampy area known as Playa Giron, which sits on the southern coast of west central Cuba and is about 100 miles from Santa Clara. Indeed, on April 17, 1961, approximately 1500 Cuban exiles and 18 American pilots,63 in the employ of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) of the United States, with full knowledge of President John F. Kennedy launched “Operation Pluto” and invaded what the US called the Bay of Pigs.64 Dreke, with military expertise, was determined to get to Playa Giron and so he asked a person who was driving a 1960 red Buick to give him a ride. Dreke rode with this person to the town of Yaguaramas, where according to Dreke, he “witnessed a moving scene. Residents of the town were asking for arms and applauding the combatants as we passed through.”65 On April 18th, he joined the 117th Battalion who had directives to get to the Bay by dawn of April 19th. Somehow the jeep Dreke was riding in got ahead of the tanks and he and his companeros were forced to engage paratroopers without much protection. He was shot in the arm and the leg.

The Bay of Pigs invasion was roundly defeated, as most of the world now knows. The revolutionary forces took control very quickly. With over 50,000 troops made up of Cuba’s Revolutionary Armed Forces, Airforce, police and militias, they were determined to not go back to being a US neo-colony. Although a secret at the time, the US administration soon after, admitted organizing the invasion and the US press called it a fiasco, a disaster, an embarrassment. Some blamed the Cuban counterrevolutionaries for not briefing the administration correctly, while the Cuban-Americans who fought for the invasion said they were poorly supported.66

In 1961, Robert E. Light, a journalist, and Carl Marzani, a former US intelligence officer, wrote a searing analysis and scathing critique of Operation Pluto, arguing that the scheme was a disaster waiting to happen. Their seventy-three page treatise was so revealing that it was censored by the CIA until its release on October 10, 2003. In it, the two authors argue that the CIA was blinded by its anti-communism and that it completely underestimated the Cuban people. The invaders, they show, were a motley crew of men wrestling internally for power. According to Light and Marzani, the underground plan was an open secret in Miami and in Guatemala where they were being trained, because they talked so much. Even Cuban radio reported on a coming invasion before it actually happened. When it failed, the entire U.S. administration had egg on its face. But intriguingly, this failure, according to Light and Marzani, led Kennedy to read Mao Tse Tung and Che Guevara and the CIA to recalibrate its cold war strategies. According to an unidentified diplomat quoted in the Wall Street Journal on April 28, 1961, “We might as well face it, Castro is not a great threat to our security by himself, it’s the danger of his doctrine spreading to other countries that’s a threat to us.”67 This notion would shape US policy toward Cuba and other countries in the global south until today.

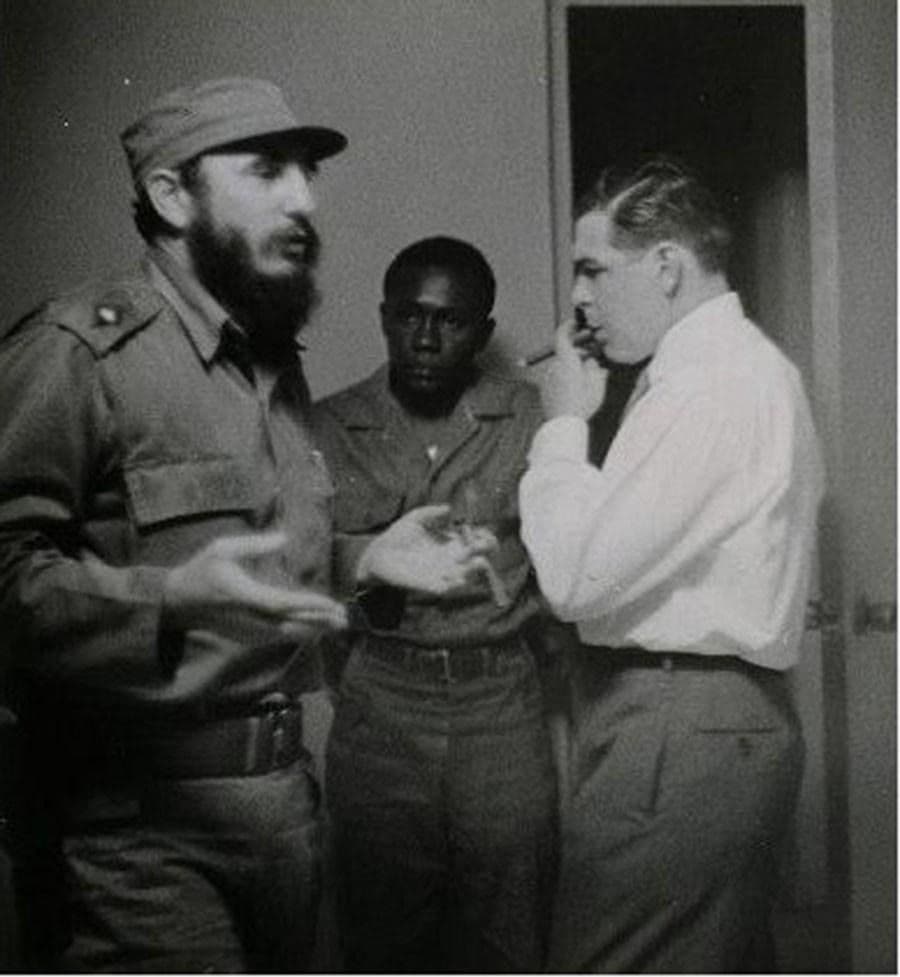

In early 1965, Victor Dreke was working in mop-up actions against the counterrevolutionaries in the Escambray.68 He was summoned to Central Army Headquarters in Havana. Once there he was asked if he would be willing to lead an international mission. He said, “of course,” but had no idea of what the mission was or where it was to be conducted. He was told at the meeting that he was to gather only black soldiers and that these black soldiers should be very black. He was surprised at this racial framing because such discourse was not normally engaged in by the revolutionary leadership. Nonetheless, he said he would do as he was asked and went to meet the commander-in-chief, Fidel Castro Ruz. While at this meeting, there was a third man in the room and Fidel asked Dreke to identify him. He responded, “I do not recognize him.” This was an important test because that man was Dr. Ernesto “Che” Guevara in disguise, who Dreke knew well. Che would need to move undetected for this mission to be successful and Fidel understood that if they could fool Dreke, the disguise was a good one (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Fidel Castro, Victor Dreke, and Che Guevara in disguise.

The destination was to be Western Tanzania. The goal, to cross Lake Tanganyika to train members of the Congolese National Liberation Army to fight for their ideals after the assassination of the Congolese leader Patrisse Lumumba.

The assassination of the charismatic and promising Belgium Congo intellectual, Patrisse Lumumba, on January 11, 1961, caused transnational outrage. Demonstrations erupted among Black Americans and Africans in the United States and among Africans and allies in Europe and in Africa. According to Brenda Gayle Plummer: “In Washington, D.C. Africans and Afro-Americans threw eggs … at the Belgium embassy. Nigerian students demonstrated at the Belgium consulate in Chicago. … Kenneth Kaunda [yet to be president of Zambia] spoke at rally in London.”69 Lumumba represented, for many, the face and voice of the new Africa. Strong and honest, he had been elected the first prime minister a mere eight months earlier of the newly independent Congo. The former colonial electorate also elected representatives from the party of Lumumba, the Congolese National Movement (MNC), to more seats than any other party.

The Belgium Congo is recognized to have been one of the most brutal colonies in Africa and yet, at the independence transition ceremony, King Leopold’s heir was patronizing, racist and painted Belgium rule as benevolent. Affronted, Lumumba spoke with clarity and frankness. He held that the new nation would work for his people and Africa and never again for colonial conglomerates. His words were viewed as an act of war by western nations. What they desired was a sham independence in which they could continue to exploit, unfettered, the country’s rich mineral reserves, especially cobalt. As Larry Devlin, then head of the CIA station in the Congo, articulated in the 2007 documentary: Cuba: An African Odyssey, he was ordered to “remove” Lumumba. While he thought of using poison toothpaste, he instead worked with a cruel general named Mobuto Sese Seku to wage a military coup and kill Lumumba.70 After the murder of Lumumba, which was indeed a Western international capital affair, Mobuto would go on to rule the country for 32 years. Renaming the country, Zaire, he did so “with a combination of brutal repression and unbridled greed, that impoverished his citizens [long after the murder of Lumumba] while netting him millions.”71

Up against the weight of Western powers, the Cuban mission in the Congo was short lived. As Che penned in Tanzania between December 1965 and January 1966, the operation was a “history of a failure.”72 He lamented this in one of his diary entrees. He also critiqued what he termed African petit bourgeois leadership styles. Many leaders, he said, spent too much time outside of the country in fancy hotels.73 And yet, as he and Dreke would note later, they learned a great deal about themselves from this failure.74 First, Che had been warned by Ben Bella of Algeria of the Organization of African Unity’s (OAU) Liberation Committee that his desire to assist in armed struggle in the Congo was unwise, given the political complexities there.75 Second, Che and Dreke also learned that even though the Cubans had military readiness, it is near impossible to do basic training in the field, especially with those who lack even rudimentary knowledge of guerilla warfare.76 For instance, the Congolese soldiers did not know how to fire and maintain weapons or prepare quietly for military engagement.77 And finally, Dreke admits that he and his men knew nothing about Africa except the stereotypes made up in Tarzan movies.78 This, of course, shaped the Cubans’ cultural frameworks and their ability to grapple with major complications with chiefly power79 and a multiethnic/national struggle that was entirely distinct from Cuba.80

Also significant was the fact that Che’s presence was discovered by spies working for both the CIA and the rebel forces. Because of this, Mobuto, with US weaponry, began bombing and surveilling the rebels’ rear base along Lake Tanganyika.

They wanted to capture or kill the well-known Che.81 The Cubans were forced to return to Cuba in November/December of 1965.

Che’s African tour in 1964 which led to the Congo mission proved valuable in manifold ways, though. Conakry, Guinea; Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania; Congo Brazzaville; Cairo, Egypt; Accra, Ghana; and Algiers, Algeria were sites where African revolutionaries and new national leaders gathered. Two meetings that would shape Cuba’s long-term role in Africa were Che’s meetings with the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (PAIGC) and the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA). Both were fighting against Portugal’s desire maintain their three territories in Africa. The third colony was Mozambique. These meetings were key; both organizations asked for food, arms and medicine, which Cuba delivered in early January 1965 and both movements had soft borders from which to operate. For the PAIGC, it was Guinea Conakry and for the MPLA, it was the Congo Brazzaville. Unlike in the Congo, it was decided that military training first take place in Cuba.

It is at this moment that one sees the emergence of what would be Cuba’s ‘solidarity as foreign policy’ strategy. An approach aimed, not at resource extraction, military might or the propping up of corrupt dictators, but one in which Cuba worked in cooperation with revolutionary movements in Africa, Latin America and Asia. Cuba’s policy was based on Che Guevara’s widely debated foco theory of guerilla warfare, in which a small number of rebels, if correctly mobilized could successfully stoke and win a revolution. Fidel doubled down on this after being forced out of the organization of American States, an organization founded and led by the U.S. Fidel in his February 4, 1962 speech, called the Second Declaration of Havana, said the “the duty of every revolutionary is to make the revolution!”82 Che, took this further in 1966 when he declared … Two, Three, Many Vietnams. “Revolutionaries,” he proclaimed, must “develop a true proletarian internationalism; with international proletarian armies; … and if we were all capable of uniting in order to give our blows greater strength and certainty, – how great the future would be, and how near!”83

According to Matt Childs, “The importance of the foco theory in Cuba’s foreign policy throughout the 1960s … cannot be overemphasized.”84 It also became the main tool [and] guiding ideology [that] provid[ed] inspiration for those insurgents who aligned themselves with Cuba.”85 Even though much of the traditional Left, such as members of the Communist International, critiqued foco theory for its attempt to speed up history and thus possibly misread objective revolutionary conditions, foco theory positioned this small Island in the Americas as an unprecedented international actor. Cuba was not, and would never, be alone. In fact, it would quickly become a global leader.

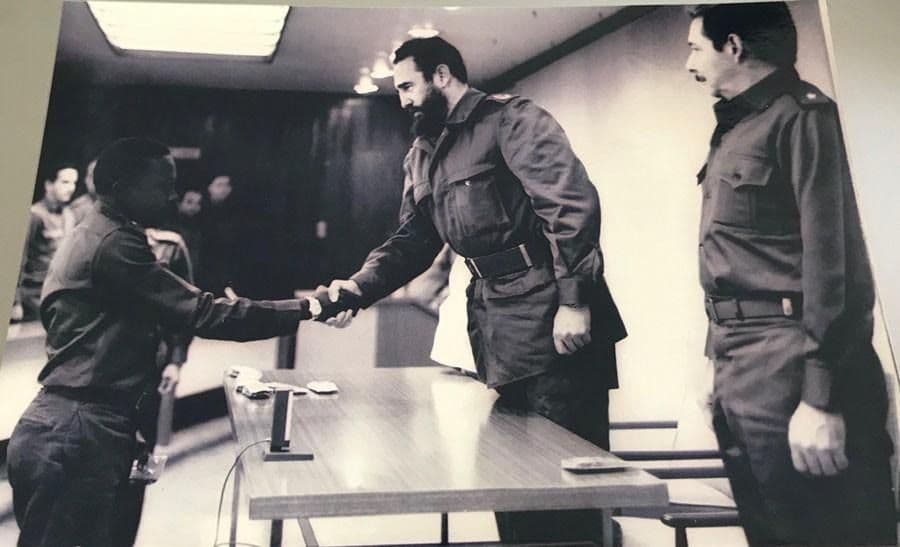

Figure 4. Victor Dreke accepting a military promotion from Fidel and Raul Castro.

Che’s Vietnam speech was read at the Tricontinental Conference held in Havana, barely two months after the Congo mission. Che, himself, was in Bolivia by that time. From January 3-15, of 1966, Cuba hosted the largest international conference of movements in the Global South since the Afro-Asian conference held in Bandung, Indonesia eleven years earlier. It brought revolutionary movements from Latin American, Asia and Africa together to strengthen cooperation and solidarity. 512 delegates and invited guests from liberation and progressive movements from 82 nations were in attendance.86 One can only imagine what Dr. Salvador Allende of Chile might have said to Josephine Baker, a black entertainer, who, while born in the United States lived much of her life France. Baker, by this time had won the French Chevalier of the L,egion d’honneur for her work during the French Resistance to Nazi occupation and had been a long supporter of Cuba.87 Allende would go on to be elected President of Chile in 1970, only to be assassinated in a US backed coup in 1973. The Organization in Solidarity with the Peoples of Africa, Asia and Latin America (OSPAAL) was established at this conference and became an important vehicle for international solidarity worldwide.

Another key person at the Conference, who made what all considered the best speech, was a non-Cuban named Amilcar Cabral, an agronomist from Guinea Bissau. Cabral had met Che only a few months earlier and was the leader of the PAIGC. He had emerged like Lumumba as a charismatic and intellectual anticolonial leader. Of his presence at the conference, Jorge Risquet, soon to be a major Cuban diplomat in Africa, said “[Cabral’s] address to the Tricontinental was brilliant. Everyone was struck by his great intelligence and personality. Fidel was very impressed by him.”88 Cabral’s half-brother and aid, Luis Cabral pointed to why the speech resonated, “Amilcar explained the history of our independence struggle,” in a way that was both subjective and objective. The speech, titled “Weapon of Theory89 continues to be a signal essay in anti-colonial literature.

Victor Dreke did not attend the Tricontinental Conference. Although on the Island, he had already begun his next assignment. Having learned from the Congo, Cuba set up a covert operation called Unidad Militar (UM) 1526, which was a military training school for Cubans and insurgents preparing for missions abroad. Moja, commandante Victor Dreke, was its Director. This unit had multiple locations on the Island and would continue to run largely under Dreke’s leadership, until 1990. This work, though, was temporarily interrupted with another call from Fidel. Dreke was needed again to go to Africa; this time he was deployed to Guinea Bissau (Figure 4).

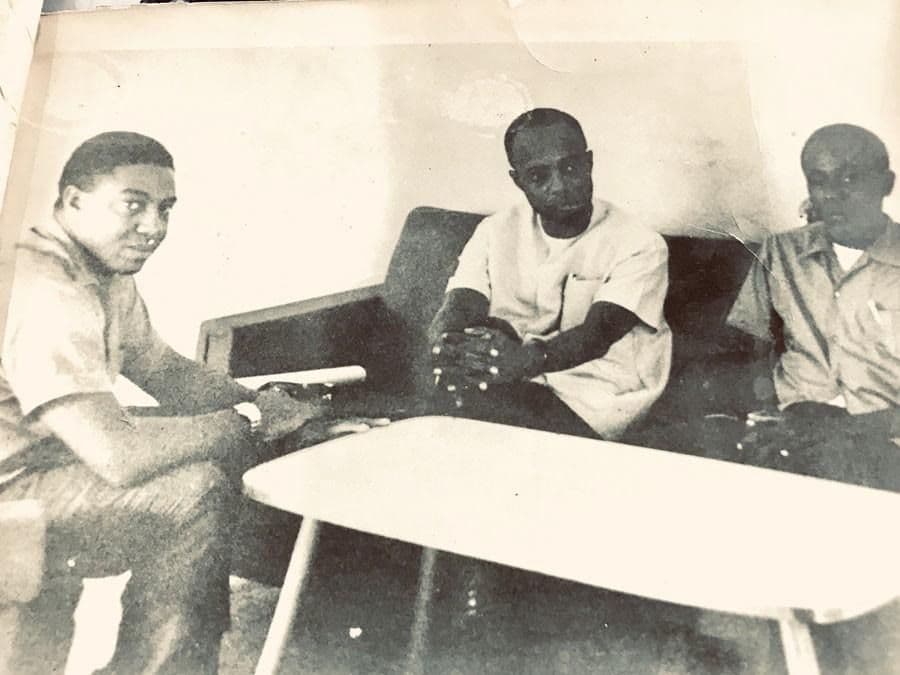

Figure 5. Another Cuban, Amilcar Cabral, leader of revolutionary anti-colonial movement in Guinea Bissau and Victor Dreke.

Although, Cabral stayed on in Cuba for some time after the Conference to confer with Fidel, he and Dreke did not meet until they were both in Guinea Bissau in February, 1967. This is somewhat ironic since Fidel took Cabral on a tour of the Escambray mountains, which Dreke knew well. In one interview, Dreke shared the awe he had for Cabral, who was already known as a “great leader among Africans” and thirteen years his senior.90 He also respected the fact that Cabral had managed to unite Guinea Bissau and the Cape Verde Islands who, although connected by Portuguese colonialism, had histories that were quite different. Moreover, like all African colonies, the west African colony was composed of varied ethnic and language groups which proved challenging for most national movements. However, Cuban Armando Entralgo writing to Raul Roa, on December 13, 1963, notes that the PAIGC was adept “in its prosecution of the people’s war. It was most successful in achieving nationalist unity, in carrying out political mobilization and in establishing new political structures in the liberated areas.”91 According to many of his contemporaries, Cabral was an unusual leader. “While he was influenced by Marxism, he was not a Marxist. ‘He came to view Marxism as a methodology rather than an ideology’, his biographer, Patrick Chabal, has remarked. ‘When useful in analyzing Guinean society, it was relied upon. When it was no longer relevant, it was amended or even abandoned. He was no ‘communist’, agreed a Cuban intelligence officer who knew him well. ‘He was a progressive leader with very advanced ideas and an extreme clarity about Africa’s problems.”92 (Figure 5)

Figure 6. Victor Dreke greets Sekou Tour,e, president of Guinea.

According to Dreke, Cubans were asked to come and train the “valiant and brave comrades”93 of the PAIGC in artillery.94 Fidel said that Cabral asked for black soldiers and so Dreke again mobilized his men, some of whom had been with him in the Congo. Importantly, they had the support of the adjacent country Guinea, that supported the PAIGC and the Cuban mission. Sekou Tour,e, then the President of Guinea Conakry, was known as a great ally of African liberation struggles. In fact, the rear base of operation was in Guinea Conakry and Dreke himself spent half of his time in Conakry and half at the front. Dreke, by this time was known as Moja and was viewed as an exceptional leader. Moja was his nom de guerre which had been given to him by Che in the Congo. “We, who had had a bitter experience in the Congo, encountered a completely different situation in Guinea Bissau.” Even though Dreke and Cabral differed in some ways on military tactics, Dreke said, “We would have preferred a more aggressive strategy,”95 “but ultimately Cabral was correct as he understood his people and the geography better than we did.”96 (Figure 6)

It was while in Guinea Bissau that Dreke learned that his comrade Che Ernesto Guevara had been killed in Bolivia, a mission that many felt he should not have taken. Nonetheless, Dreke wrote: “This has been a very heavy blow for all of us here, but we all know very well that we will achieve nothing with tears or acts of desperation and my advice to all the compan~eros has been to remain calm and to redouble their efforts. You know what Che means for all of us … But I know that right now we need to be calm and resolute, because every one of us is needed to continue the work that Che began.”97

Dreke returned to Cuba in late 1968, leaving the PAIGC military in a stronger position. The Cuban mission with the PAIGC, though, lasted until the war ended in 1974. Dreke did not go to Angola which was Cuba’s largest military mission in Africa, seconded by Guinea Bissau. He did train many soldiers, though, who did go. Because Angola is an oil rich country, there were western interests working to stop the most popular and socialist movement, the MPLA, from taking power in 1974. Nearly 300,000 Cubans served in Angola and by so doing, kept Angola from going the way of the Congo. Nonetheless, a war of stalemate, did continue in the south of the country until 1990. The South African apartheid regime and the United States worked with the tribalist, anti-communist Jonas Savimbi and his UNITA for 25 years in hopes of toppling the MPLA who were aided by the Cubans. They never did. Successes by the Cuban and Angolan army and air force along with the global anti-apartheid forces ultimately led to an end of the war, which the US brokered.98 The final set of Cuban troops returned home from Angola in 1991.

Comandante Victor Dreke, because of his sacrifice and skill gained a tremendous amount of respect from those that served under him in both the Congo (Zaire) and Guinea Bissau and Cape Verde and those he trained in Cuba. According to Reynaldo Batista, who served with Dreke in the Congo, “Dreke has always been a role model,” “Very simple, very austere.” According to Piero Gleijeses who interviewed those who served under Dreke, it is clear that “the power of his example and his quiet charisma were evident. Time and time again, I heard the same words of respect.”99 They all said they learned a great deal from Moja, who was an exceptional leader.

From 1968 until 1990, Victor Dreke was head of the Political Directorate of the Revolutionary Armed Forces. In this capacity, he supervised the key school in Cuba that trained Africans and Cubans for military missions in Africa. He received a degree in politics from the M,aximo Go,mez Military Academy and a law degree in 1981 from the University of Santiago de Cuba. He returned to civilian life in 1990, where he has served as president of the Cuba-Africa Friendship Association, and has held various leadership positions in the Association of Combatants for the Cuban Revolution. He and his wife, Ana Morales, a medical doctor, who also worked in Africa continue to engage in solidarity with Africa.

1. Victor Dreke, interview by Lisa Brock, audio, Havana, Cuba, March 20, 2015.

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid.

4. See Melina Pappademos, Black Political Activism and the Cuban Republic, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 2011), 6; Gillian McGillivray, Blazing Cane: Sugar Communities, Class, and State Formation in Cuba, 1868–1959 (Duke University Press, 2009), 10. Dreke said that his father did join the Authentic Party after 1944 which had political power from 1944-1952, Victor Dreke, interview by Lisa Brock, audio, Havana, Cuba, March 20, 2015.

5. Las Villas was known for strong cross racial networks of the Liberal Party dating back to 1906 when Jose Miguel Gomez, who was from the region, became President. McGillivray, Blazing Cane, 82.

6. Victor Dreke, interview by Lisa Brock, audio, Havana, Cuba, March 20, 2015.

7. Bureau of the Census Library, CUBA: Population, History and Resources, 1907 (Washington, DC: Bureau of the Census Library, 1909), 152-53.

8. Alejandro de La Fuente, A Nation for All: Race, Inequality and Politics in the Twentieth Century (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001), 64.

9. Oscar Pino-Santos, Cuba Historia y Economia (Editorial Ciencias Sociales, La Habana, 1983), 483-484; Victor Dreke, interview by Lisa Brock, audio, Havana, Cuba, March 20, 2015.

10. Fernando Ortiz, Cuban Counterpoint: Tobacco and Sugar (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.), 54.

11. According to John T. Skelly and Harold Lidin, “Sagua typifies the sweating sugar towns whose toll builds the Havana palaces … It’s milk and honey country all the way; the verdant cane-covered tableland tilts just enough to keep the placid Sagua river coursing its way to the Atlantic., John T. Skelly and Harold Lindin, “Pea-Shooters vs. Machine Guns: Why Castro’s Revolt Sputters,” The Minneapolis Star, (April 18, 1958).

12. McGillivray, Blazing Cane, 38; See also, Ada Ferrer, Insurgent Cuba, Race, Nation and Revolution (1868-1898), 18.

13. Phillip S. Foner, The Antonio Maceo: The “Bronze Titan” of Cuba’s Struggle for Independence (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1977), 196.

14. “Antonio Maceo to the People of Las Villas,” Remedios, December 5, 1895, Francisco de Paula Coronado Collection, 1895, in Phillip S. Foner, 201.

15. See, Louis A. Perez, Jr. Cuba: Between Reform and Revolution (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), 122; Jaime Suchlicki, Cuba: From Columbus to Castro, second edition, revised, (Washington, DC: Pergamon-Brasseys International Defense Publishers, 1987), 70.

16. Ada Ferrer, Insurgent Cuba: Race, Nation, and Revolution, 1868-1898 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press), 174.

17. “The Killing of Bandera: Negro General and Two Companions Shot and Slashed to Death,” The New York Times, August 24, 1906.

18. “The Killing of Bandera: Negro General and Two Companions Shot and Slashed to Death,” The New York Times, August 24, 1906.

19. “The Killing of Bandera: Negro General and Two Companions Shot and Slashed to Death,” The New York Times, August 24, 1906.

20. Christobelle Peters, Crossing the Black Atlantic to Africa: Research on Race in ‘Race-less’ Cuba, New Perspectives on the Black Atlantic: Definitions, Readings, Practices, Dialogues (Bern, Switzerland: Peter Lang, 2012), 92.

21. Moni Basu, “Che’s work in Africa given new scrutiny,” Atlanta Constitution October 30, 2002, 66.

22. Jorge Ibara, Prologue to Revolution: Cuba, 1898-1958, (Boulder, CO: Lynne Reinner Publishers, 1998), 141.

23. “The Killing of Bandera: Negro General and Two Companions Shot and Slashed to Death,” The New York Times, August 24, 1906.

24. Ibid; “Cuban Republic’s Army, Composed of Rural Guards and the Artillery Corps,” The New York Times, June 26, 1902; Allen R. Millett, “The Rise and Fall of the Cuban Rural Guard, 1898-1912,” The Americas, vol. 29, No. 2. October, 1972, 191-213.

25. It was during this administration in 1933 that women got the right to vote in Cuban elections.

26. “Assassination in Cuba,” New York Times, October 30, 1956.

27. De La Fuente, A Nation for All: Race, Inequality and Politics in the Twentieth Century (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001),194; Devyn Spence Benson, Antiracism in Cuba: the Unfinished Revolution (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press), 184.

28. Ibarra, Prologue to Revolution, 17.

29. McGillivray, Blazing Cane, 250.

30. “Cuban Sugar Workers Want Guarantees,” Miami Daily News, Sunday, April 28, 1946; “State Department Partly to Blame for High Sugar Price,” The Gazette and Daily (York, PA), October 4, 1946. “Red Sugar Chief States Cuban Aims,” Daily News, December 8, 1947, 66; “Cuban Sugar Workers Ask 44-Hour Week,” Tampa Morning Tribune, December 21, 1948; “Cheaper Food Sent to Cuba Guarantees U.S. More Sugar,” The Berkshire Evening Eagle, March 15, 1947; McGillivray, Blazing Cane, 250.

31. “Cuban Red Deputy Slain: President Sifts Killing of Menendez, Chief of Sugar Unions,” New York Times, January 3, 1948; The Cia was established in 1947 and the Truman, US President, anti-communist cold war doctrine in 1948.

32. Victor Dreke, From the Escambray to the Congo: in the Whirlwind of the Cuban Revolution (New York: Pathfinder Press, 2002), 51.

33. Victor Dreke, interview by Lisa Brock, audio, Havana, Cuba, March 20, 2015.

34. Dreke, From the Escambray to the Congo, 54.

35. Victor Dreke, interview by Lisa Brock, audio, Havana, Cuba, March 20, 2015; Dreke, From the Escambray to the Congo, 54.

36. Victor Dreke, interview by Lisa Brock, audio, Havana, Cuba, March 20, 2015.

37. Marifelli Perez-Stable, The Cuban Revolution: Origins, Course, and Legacy (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 53.

38. Dreke, From the Escambray to the Congo, 52.

39. Victor Dreke, interview by Lisa Brock, audio, Havana, Cuba, March 20, 2015.

40. Dreke, From the Escambray to the Congo, 53.

41. U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Foreign Commerce, Investment in Cuba (Washington, D.C., 1956), 10 in Leland T. Johnson, “U.S. Business Interests in Cuba and the Rise of Castro,” World Politics, 17, no. 3 (1965):443.

42. Victor Dreke, interview by Lisa Brock, audio, Havana, Cuba, March 20, 2015.

43. Ibid.

44. Julia E. Sweig, Inside the Cuban Revolution: Fidel Castro and the Urban Underground (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2004), 12-13.

45. Victor says that after the triumph of the revolution, people from his neighborhood were so proud that they all claimed to have been a part of his escape.

46. Ibarra, Prologue to Revolution, 170.

47. Victor Dreke, interview by Lisa Brock, audio, Havana, Cuba, March 20, 2015.

48. It is important to note that the eastern part of the Island has always been considered more Caribbean in culture than and more Latin American Havana.

49. R. Hart Phillips, “Cuba Rebels open a ‘Second Front’ Youthful Insurgents Raid Military Post in South Coast Mountain Area,” The New York Times, January 28, 1958.

50. R. Hart Phillips, “Rebels Claim 80 of a Province at Fierce Cuban Fight Continues,” The New York Times, December 30, 1958,

51. Jay Mallin, “Still in Revolt’s Grip, Cuba Yearns for Peace,” The Miami News, Wednesday, January 1, 1958.

52. Victor Dreke, interview by Lisa Brock, audio, Havana, Cuba, March 20, 2015

53. Ibid.

54. Associated Press, “Revolt at Critical Peak,” The New York Times, December 30, 1958.

55. Spence Benson, Antiracism in Cuba: the Unfinished Revolution, 92.

56. Ibid, 92.

57. Richard R. Fagan, Cubans in Exile: Dissatisfaction and the Revolution (Stanford University Press, 1968), 17; Maria Cristina Garcia, Havana, USA: Cuban Exiles and Cuban Americans in South Florida, 1959-1994 (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1996), 1, 15; Mark Sawyer, Racial Politics in Post-Revolutionary Cuba (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press 2006), 157; “Cuban Migration: A Postrevolution Exodus Ebbs and Flows,” Migration Policy Institute, July 17, 2017; Spence Benson, Antiracism in Cuba: the Unfinished Revolution, 135.

58. See Mirta Oito, “Best of Friends, Worlds Apart,” The New York Times, June 5, 2000; Tim Padgett, “Miami’s Cuban Cubicle’ Creates Isolation that Fosters Racism – And Blackface,” WLNR, Miami Florida, May 30, 2018.

59. Sagua had many US agencies representing many products for export. This agency was involved in the import and export of lumber/timber. For earlier engagement in wood commerce, see David Demeritt “Boards, Barrels, and Boxshooks: The Economics of Downeast Lumber in Nineteenth-Century Cuba,” Forest & Conservation History, Vol. 35, No. 3, July, 1991, 108-120.

60. R. Hart Phillips, “Castro Reported Pursuing Rebels With 5,000 Troops,” The New York Times, April 16, 1960; “Havana Reports, Revolt Crushed,” The New York Times, October 10, 1960.

61. Dreke, From the Excambray to the Congo, 111.

62. Jorge Ibarra, describes serious disparities between the capitol of Havana and the rest of the country. For example, during the 1950s, Havana had one hospital bed for every 195 inhabitants while Las Villas had one for every 1,333 inhabitants. Oriente had one hospital bed for every 1,870 inhabitants. Catherine Murphy, director, Maestra, 2014. These figures are representative of all indices.

63. Robert Light and Carl Marzani, Cuba Versus the C.I.A, (New York: Marzani and Munsell Publishers, Inc. 1961), 19.

64. Rowland Evans and Robert Novak, “US Officials Haven’t Learned Lessons from Bay of Pigs Fiasco,” Newport News, Virginia, June 4, 1964; “The Great Betrayal,” The Shreveport Times, April 17, 1963.

65. Dreke, From Escambray to the Congo, 113.

66. “Failure was the Word from the Very Start,” The New York Times, May 24, 1964; “Kennedy Near Tears Over Bay of Pigs,” The New York Times, July 19, 1965; “Bay of Pigs Planner Cites Errors of 1961,” The New York Times, July 21, 1965; Robert Pear, “The Pointing of Fingers and the Bay of Pigs,” The New York Times, December 30, 1987, B6.

67. A Curator’s Pocket History of the CIA, CIA Website, July 21, 2019, 4:30pm.

68. Victor Dreke, interview by Lisa Brock, audio, Havana, Cuba, March 20, 2015.

69. Brenda Gayle Plummer, Black Americans and US Foreign Affairs, 1935-1960 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996), 303.

70. Jihan El Tahri Paris, Cuba: An African Odyssey, (France: Arte, 2007).

71. John Daniszewski and Ann M. Simmons, “Mobuto, Zairian Dictator for 32 years, Dies in Exile,” Los Angeles Times, September 8, 1997.

72. Che Guevara, The African Dream: The Diaries of the Revolutionary War in the Congo (London: The Harvill Press, 2001), 1.

73. Che also critiqued Tanzania for having initially promised military support, but pulled out due to negotiations with others made later. Christabelle Peters, “When the ’New Man’ Met the “Old Man: Guevara, Nyerere, and the Roots of Latin-Africanism,” in Jennifer L. Lambe and Michael J. Bustamante, The Revolution from Within: Cuba, 1959-1980 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019), 175-180.

74. Victor Dreke, interview by Lisa Brock, audio, Havana, Cuba March 13, 2018; Dreke argues, that “the action of those campa~ who fell in the Congo was not in vain … . The neros experience we gained made it possible for us to do what we did to aid the liberation struggles in Guinea-Bissau, Angola, and other places.”

75. Peters, “When the New Man … ,” 172.

76. Che Guevara, The African Dream: The Diaries of the Revolutionary War in the Congo, (London: The Harvill Press, 2001), xxxi.

77. Victor Dreke, interview by Lisa Brock, Audio, Havana, Cuba, March 13, 2018.

78. Victor Dreke, interview by Lisa Brock, audio, Havana, Cuba, August 10, 2016; Moni Basu, Atlantic Constitution, 66.

79. William Galvez, Che in Africa: Che Guevara’s Congo Diary, (Melbourne: Ocean Press, 1999), 213.

80. And very importantly, one who was killed and whose body was seized by the enemy had underwear that said made in Cuba. This was a major error on the Cubans part. According to Dreke, they should have had no clothes on them that linked them to Cuba.

81. Ibid.

82. Fidel Castro, The Second Declaration of Havana, http://www.walterlippmann.com/fc-02-04 1962.html. Edited by Walter Lippmann based on the Cuban English language edition of 1962.

83. Che Guevara, “Create Two, Three, many Vietnams,” Speech at the Tricontinental Conference for the Peoples of Asia, Africa and Latin America, January 6, 1966, Havana, Cuba, in Ernesto Che Guevara and David Deutschmann, Che Guevara Reader: Writings on Politics and Revolution, (Melbourne: Ocean Press, 2003), 361, 362.

84. Matt D. Childs, “An Historical Critique of the Emergence and Evolution of Ernesto Che Guevara’s Foco Theory,” Journal of Latin American Studies, 27, no. 3 (1995), 596.

85. Ibid, 598.

86. Anne Garland Mahler, From the Tricontinental to the Global South: Race, Radicalism and Transnational Solidarity (Raleigh, NC: Duke University Press, 2018), 3.

87. Mary Dudziack, Josephine Baker, “Racial Protest, and the Cold War,” The Journal of American History, 81(2)(1994), 543-570.

88. Piero Gleijeses, Conflicting Missions (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002), 187.

89. Amilcar Cabral, “Weapon of Theory,” Speech at the Tricontinental Conference for the People’s of Asia, Africa and Latin America, January 6, 1966, Havana, Cuba. Marxist Writers Archive, https://www.marxists.org/subject/africa/cabral/1966/weapon theory.htm; Ndangwa Noyhoo, “Revisiting Cabral’s ‘weapon of theory,” Pambazuka News, January 22, 2014, https://www.pambazuka.org/governance/revisiting-cabral%E2%80%99s weapon-theory.

90. Victor Dreke, interview by Lisa Brock, audio, Havana, Cuba, March 13, 2018.

91. Piero Gleijeses, “The First Ambassadors: Cuba’s Contribution to Guinea-Bissau’s War of Independence,” Journal of Latin American Studies, 29, no. 1 (1997), 46.

92. Ibid, 47.

93. Interview, audio, March 15, 2018.

94. Interview, audio, March 15, 2018.

95. Ibid.

96. Ibid.

97. Gleijeses, “The First Ambassadors,” p. 50.

98. The successes were: Cubans and Angolan air forces defeat the South Africans in air battle, known as the Battle of Cuito Cuanavale, in 1988; the Namibians with long support from the United Nations became independent of South Africa in 1988, the people in South Africa made their country ungovernable from 1985-1990 and Nelson Mandela was released in 1990. The United States government steps in, without invitation, to broker a cease fire and troop withdrawal of both the South Africans and Cubans.

99. Piero Gleijeses, Conflicting Missions, 191.