VOL. 20

Seven Billion Reasons for Reparations

Marcus Anthony Hunter

ABSTRACT

DOWNLOAD

SHARE

Negroes distrust all saving institutions since the fatal collapse of the Freedmen’s Bank.

—W.E.B. DuBois (1899, 284)1

Although it has been 400 years since the first slave ship arrived at the Eastern shores of the United States, the federal government has only offered anemic solutions to redress the well-documented suffering of Black people under the state- sanctioned White Supremacist, capitalist, and anti-Black regime better known as American Slavery. For more than 150 years, a persistent though deeply contested debate has ensued regarding the authorization of reparations to reconcile and recognize the inhumane, involuntary, and generational devastation begat by the enslavement of Black Africans. Despite the formal ending of legal slavery in the United States in 1865, a subsequent series of consequential systems and practices of racial domination emerged in its place. Like a thousand-headed snake, the abolishment of American slavery, as numerous scholars and activists have noted, was immediately followed by forms of neo-slavery: sharecropping, the regime of Jim Crow segregation and racial subordination, the Prison Industrial Complex, urban renewal, urban dispossession, and police brutality. Informed by similar notions of racial domination endemic to American slavery, neo-slavery formations mark both the enduring legacies of Black enslavement and ever more legitimate claims and reasons for reparations.

Whether litigated through tort claims or powerfully articulated in scholarly and public outlets, reparations proponents have emphasized estimated costs incurred by and debts owed to the descendants of enslaved Black Americans. Such costs can be found in sociopolitical and economic calculations for the uncompensated and stolen Black labor, the loss of property, the loss of homespace and heritage, forcible rape, lynching, the loss of opportunity, and continued systems and practices of racial capitalism and racial domination. These costs, then, also underscore a myriad of debts the United States owes and that a reparations framework is meant to collect.

As reparations debates and campaigns continue, it is essential to broaden our historical frame and examine those failed experiments that, albeit briefly, sought to provide some modicum of redress for formerly enslaved people. Here, the period W.E.B. Du Bois defined as Black Reconstruction (1863–1879) has important lessons to offer. The era contains key freedom experiments that, while profoundly consequential, have become long forgotten and often obscured in favor of a history of injury that emphasizes state-sanctioned policies of racial segregation and racial domination.

To this end, this article reanimates and retells the story of the Freedmen’s Bank (1865–1974), the first and only nationalized and federally established Black bank in the United States. During its short-lived history, the Freedmen’s Bank comprised thirty-four branches and held $3,299,201 ($73,300,0002 in 2018 dollars), all from Black depositors. Closed abruptly in 1874, to this day the bank’s Black depositors have never received their money back in full. Rooted in documented and recorded financial losses, this article expands and further legitimizes claims for economic reparations—monetary repayment to the descendants and injured parties based upon estimated costs and debts that persist into America’s racial present and the foreseeable future.

The Bank that Lincoln Built

Several factors led to the rise of the Freedmen’s Bank: the emancipation of Black Americans, increased migration of Black Americans throughout the United States, and increased pay to Black soldiers.3 For example, reported cases of Black soldiers swindled by White economic predators were a common occurrence. “Swindlers of every kind were always ready for pay day in a Negro regiment,” as economic historian Walter Fleming uncovers, “and had little difficulty in getting most of the soldiers’ cash.”4 Such experiences of Black soldiers revealed to some the vulnerability of Black laborers and their wages in the American marketplace.

As a result, at the conclusion of the Civil War, Northern (and to some extent Southern) White leaders lobbied Congress to authorize and create a bank for Black Americans. Proponents contended that the bank be loosely affiliated with the Freedmen’s Bureau, the federal institution charged with overseeing and facilitating the process of Black emancipation following the war’s conclusion. Following a meeting of key political and business leaders on January 27, 1865, plans proposing the Freedmen’s Bank were sent to the U.S. Congress.5 Congress swiftly approved the creation and incorporation of the banking institution, outlining its responsibilities:

The general business and object of the corporation hereby called shall be to receive on deposit such sums of money as may from time to time be offered, therefore by or on behalf of persons heretofore held in slavery in the United States or their descendants and to invest the same in stocks, bonds, treasury notes and other securities of the United States.6

On March 3, 1865, President Abraham Lincoln signed the legislation “The Freedmen’s Bank Act,” authorizing the organization of the bank. As Lincoln signed the legislation, he celebrated it as a significant step in the transition from enslavement to full citizenship: “This bank is just what the freedmen need.”7 Though an early advocate of a nationalized banking system, Lincoln had not been able to actualize this vision as a part of his presidency given the Civil War context. However, with the war concluded Lincoln used this window of transition to establish the Freedmen’s Bank, a chance to finally begin this national experiment even if it would only involve Black people’s money. Lincoln’s assassination would occur just a month later.

The Freedmen’s Bank was quickly organized and received tremendous Black investment, and the support of prominent White businessmen and politicians with varied motives. Additionally, the announcement of the bank came alongside the report that the U.S. government would protect the savings of the bank. Black support and confidence in the new banking institution was gained largely by way of recruitment, advertisement, and outreach. Chief in the outreach effort was the bank’s corresponding secretary (and inspector and superintendent of schools for the Freedmen’s Bureau), White northerner John W. Alvord. Alvord, a minister and former attach,e to General William Tecumseh Sherman during the Civil War, was an early booster for the Freedmen’s Bank.

Serving as its initial president, Alvord traveled throughout Black areas of the South to encourage Blacks to deposit their incomes and savings at the bank. Alvord’s most successful strategy involved convincing potential depositors that the bank “was part of the Freedmen’s Bureau system.” Alvord traveled through the South with an endorsement from General O.O. Howard, the Commissioner of the Freedmen’s Bureau, representing this letter of support for the bank “as an order from Howard that the Negro soldiers should deposit their bounty money with him.”8 Ambivalent Black depositors, nevertheless, found Howard’s words compelling: “I consider the Freedman’s [sic] Savings and Trust Company to be greatly needed by the colored people, and have welcomed it as an auxiliary to the Freedmen’s Bureau.”9

Once a member, depositors received materials that included more economic and governmental propaganda to ensure their loyalties to the new bank. One version of the passbook, for example, featured the following statement: “The Government of the United States has made this bank perfectly safe.”10 Another edition of the passbook, for instance, featured photographs of Lincoln, General Ulysses S. Grant, the United States flag, and a poem likely penned by General Howard encouraging Black depositors to be frugal with their savings at the bank:

‘Tis little by little the bee fills his cell; And little by little a man sinks a well; ‘Tis little by little a bird builds her nest; By little forest in verdure is drest.

‘Tis little by little great volumes are made; By littles a mountain or levels are made; ‘Tis little by little an ocean is filled;

And little by little a city we build.

‘Tis little by little an ant gets her store; Every little we add to a little makes more;

Step by step we walk miles, and we sew stitch by stitch; Word by word we read books, cent by cent we grow rich.11

The proponents of the Freedmen’s Bank were also advocates of frugality and saving as important economic ideals that would advance the needs of Black Americans in the post-Emancipation period.

Thus, the bank is best understood as both a federally supported Black financial institution and as a metaphor for Black economic practices and progress in postEmancipation America. Promotional material like the aforementioned poem also demonstrates how the Freedmen Bank’s White management used a range of political and financial propaganda to influence Black Americans’ relationship to their money and the relationship such monies shared with citizenship. This mantra of frugality, however, was conditioned by the relegation of Black incomes and savings to a separate and “special” banking institution structure mostly concerned with collecting savings rather than providing loans, at least initially.12

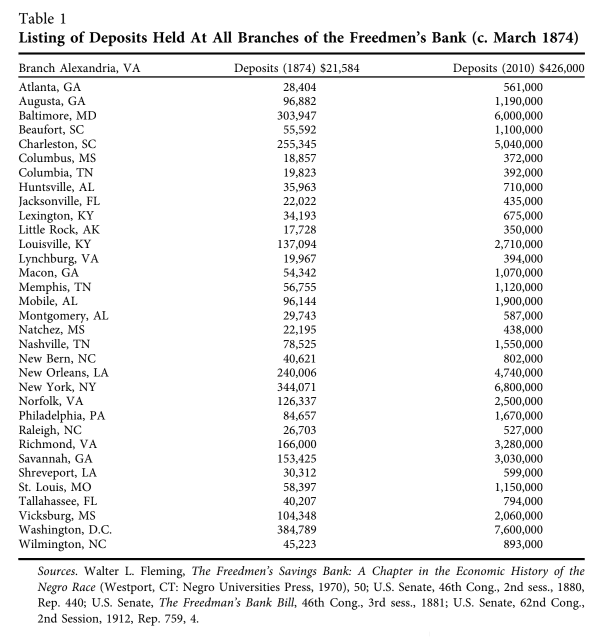

Due to such recruiting efforts, the bank’s list of Black depositors grew quickly, and soon thirty-four branches were established in locations across the country, including Philadelphia. A reporter in Charleston, South Carolina was taken with what he observed at the branch one afternoon in 1870: “Go in any forenoon and the office is found full of negroes depositing little sums of money, drawing little sums, or remitting to distant part of the country where they have relatives to support or debts to discharge."13 As Tables 1 and 2 indicate, by January 1874, less than ten years after the establishment of the Freedmen’s Bank, deposits at the thirty-four branches totaled $3,299,201 ($73,300,000 in 2018 dollars). Spanning the North and South, as Table 1 indicates, Freedmen’s Bank branches included locations such as Atlanta, Baltimore, New Orleans, New York, and St. Louis (to name a few). The New York and Philadelphia offices, the only two northern branches of the Freedmen’s Bank, held total deposits of $344,071 and $84,657 ($7,640,000 and $1,880,000 in 2018 dollars) respectively.14

Table 1. Sources. Walter L. Fleming, The Freedmen’s Savings Bank: A Chapter in the Economic History of the Negro Race (Westport, CT: Negro Universities Press, 1970), 50; U.S. Senate, 46th Cong., 2nd sess., 1880, Rep. 440; U.S. Senate, The Freedman’s Bank Bill, 46th Cong., 3rd sess., 1881; U.S. Senate, 62nd Cong., 2nd Session, 1912, Rep. 759, 4.

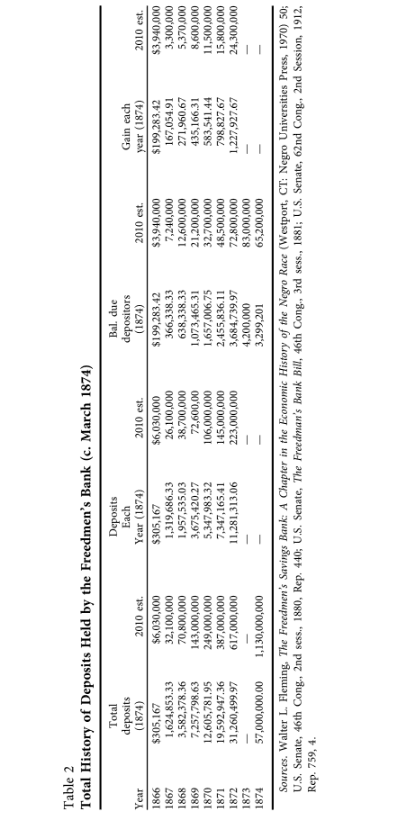

The Freedmen Bank’s success led to an expansion in its function from largely a home for savings to one that was also a loan-lending institution. This shift was accomplished when Congress amended the bank’s charter in 1870. “Before the charter was amended in 1870, no loans could be made by the principal bank or by the branches, for, by the law of 1865, two thirds of all deposits” were to be “invested in United States securities and the remainder held as an available fund.15 After 1870, however, Congress provided a stipulation that allowed the bank to provide mortgages and business loans.

These mortgages and loans were most often given to Whites, representing an important paradox—a Black bank using the savings and income of Black depositors to advance the economic fortunes of Whites who had mainstream banks and disproportionately benefited from the marketplace generated by racial capitalism. This contradiction would soon show itself, as the liabilities created because of lending began to disrupt the viability of various branches. Black depositors were set up to shoulder all the risks, with Whites benefiting from the frugality of those depositors.16

Table 2. Sources. Walter L. Fleming, The Freedmen’s Savings Bank: A Chapter in the Economic History of the Negro Race (Westport, CT: Negro Universities Press, 1970) 50; U.S. Senate, 46th Cong., 2nd sess., 1880, Rep. 440; U.S. Senate, The Freedman’s Bank Bill, 46th Cong., 3rd sess., 1881; U.S. Senate, 62nd Cong., 2nd Session, 1912, Rep. 759, 4.

Sparked by reports of corruption by White officials who managed the Freedmen’s Bank, confidence in the bank began to erode. For example, in 1872 a rumor that deposits held in North Carolina were used to support politicians, including Ulysses S. Grant’s presidency, caused a heavy run on the branches there.17 Soon after, rumors tying the deposits at the Freedmen’s Bank with political campaigns spread widely and took out $500,000 ($11,100,000 in 2018 dollars) of the bank’s total holdings. Rumors aside, there were also very real accounting issues and serious deficits. Of the thirty-four branches established, half were operating with large deficits, often due to bad loans that had been authorized to the detriment of the bank.18

As White officials left the bank, they were replaced by Black employees, who were often inexperienced in the area of banking and unable to shoulder the burden of restructuring a complex and fragile financial institution. Things began to unravel; depositors arrived at branches across the country seeking the return of their savings in full. In an effort to win back the confidence of Black depositors, in March 1874 Frederick Douglass was appointed to head the Freedmen’s Bank.19 However, even the great abolitionist could not work miracles and was unable to stop the runs on the bank’s branches.

We need only look to Douglass’ “fair and unvarnished narration of [his] connection with” the Freedmen’s Savings Bank to ascertain the inner workings of the bank under his leadership. Framing the arrangement as unknowingly being “married to a corpse,”20 Douglass provides tremendous insights regarding the last days of the Freedmen’s Bank:

I had read of this Bank when I lived in Rochester, and had indeed been solicited to become one of its trustees, and had reluctantly consented to do so.

… After four months before this splendid institution was compelled to close its doors in the starved and deluded faces of its depositors, and while I was assured by its President [John Alvord] and by its Actuary of its sound condition, I was solicited by some of its trustees to allow them to use my name in the board as a candidate for its Presidency. So I waked [sic] up one morning … to hear myself addressed as President of the Freedmen’s Bank.

… On paper, and from the representations of its management, its assets amounted to three million dollars, and its liabilities were about equal to its assets. With such a showing I was encouraged in the belief that by curtailing expenses … we could be carried safely through the financial distress then upon the country. … The more I observed and learned the more my confidence diminished. … Some of them, while strongly assuring me of its soundness, had withdrawn their money and opened accounts elsewhere. Gradually I discovered that the Bank had sustained heavy losses at the south through dishonest agents, that there was a discrepancy on the books of forty thousand dollars, for which no account could be given, that instead of our assets being equal to our liabilities we could not in all likelihoods of the case pay seventy-two cents on the dollar.21

Although Douglass had been assured that the financial condition of the bank was sound, he soon discovered that such assurances were indeed false, and reported the matter to the chairman of the Senate Committee on Finance. Congress then decided to liquidate the bank’s affairs, officially closing the bank on June 28, 1874. Despite rapid movement to close the bank, nearly ten years later many of the Black depositors’ money had not been returned.

In a speech at the “Convention of Colored Men” on September 25, 1883, in Louisville, Kentucky, Douglass called out the U.S. government for it woeful handling of the bank’s affairs.22 Urging Congress to recover and guarantee the savings of the thousands of Black depositors facing huge losses, Douglass offered the earliest economic reparations claims based upon the experience and closure of the Freedmen’s Bank:

The colored people have suffered much on account of the failure of the Freedman’s [sic] bank. Their loss by this institution was a peculiar hardship, coming as it did upon them in the days of their greatest weakness. It is certain that the depositors in this institution were led to believe that as Congress had chartered it and established its headquarters at the capital the government in some way was responsible for the safe keeping of their money. Without the dissemination of this belief it would never have had the confidence of the people as it did nor have secured such an immense deposit. Nobody authorized to speak for the Government ever corrected this deception, but on the contrary, Congress continued to legislate for the bank as if all that had been claimed for it was true. Under these circumstances, together with much more that might be said in favor of such a measure, we ask Congress to reimburse the unfortunate victims of that institution, and thus carry hope and give to many fresh encouragement in the battle of life.23

This speech was also significant because Douglass’ reputation took a significant hit due to the failings of the bank. Although the closure of the bank had little to do with his management, the Freedmen’s Bank debacle had jeopardized his reputation as a Black advocate and fighter for Black freedom. Douglass intimated, “When I became connected with the bank I had a tolerably fair name for honest dealing … but no man there or elsewhere can say I ever wronged him out of a cent.”24 As Douglass’ example demonstrates, the financial confidence of Back Americans and confidence in and reputation of Black leadership of the time were at stake.

By 1900 only $2,045,504.62 ($61,600,000 in 2018 dollars), or 62 percent, of the total amount of deposits prior to the bank’s failure had been paid. To be clear, the repayment of 62 percent of the deposits did not mean that 62 percent of the depositors were repaid. Instead, repayment was piecemeal, leaving many without any sign that their savings would ever be returned. In the end, many Black depositors lost their savings, receiving little to no money back from the bank or the U.S. government.25 Even more, the 38 percent or $1,253,696.38 (37,800,000 in 2018 dollars) that remain unpaid carry a relative value amount of $1,180,000,000 in 2018 dollars were it to be converted into an economic share of Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

Soon general distrust of banks set in among Blacks across the United States. Douglass was not the only Black leader disappointed and duped by the bank, as southern Black leader and avid proponent of economic self-sufficiency Booker T. Washington also indicated the psychological toll the bank’s collapse took on Black depositors:

[Freedmen’s] bank had agents all over the South, and coloured [sic] people were induced to deposit their earnings with it in the belief that the institution was under the care and protection of the United States Government. When they found out that they had lost, or been swindled out of all their savings, they lost faith in savings banks, and it was a long time after this before it was possible to mention a savings bank for Negroes without some reference being made to the disaster of the Freedman’s [sic] Bank. The effect of this disaster was more far-reaching because of the wide extent of territory which the Freedmen’s Bank covered through its agencies.26

Noted Black sociologist and Washington-rival, Du Bois, too, saw the financial collapse as distinctly tied to a collapse in Black confidence in banking:

Then in one sad day came the crash [of the Freedmen’s Bank]—all the hardearned dollars of the freedmen disappeared; but that was the least of the loss— all the faith in saving went too, and much of the faith in men; and that was a loss that a Nation which to-day sneers at Negro shiftlessness has never yet made good. Not even ten additional years of slavery could have done so much to throttle the shift of the freedmen as the mismanagement and bankruptcy of the series of savings banks chartered by the Nation for their especial aid.27

As we find in Du Bois’ assertion, the loss of Black Freedmen and Freedwomen’s first monies after Emancipation was a tremendous blow to the freedom struggle and Black confidence in financial and state-sanctioned institutions. Most striking is Du Bois’ comparison of the bank’s collapse to “ten additional years of slavery,” as such a comparison reveals the dispossession and psychological damage that took place in the wake of the bank’s collapse. Even more, Du Bois’ juxtaposition of slavery and the Freedmen’s Bank highlights the problems of racial exclusion that persisted even as newly emancipated Black citizens were making economic gains.

Just as Black people were experiencing wage-labor and early mobility, the unfulfilled promises of the Freedmen’s Bank stunted their economic livelihoods. Not only were Black depositors not being repaid, their money was given to mostly well-to-do Whites, and mainstream banks continued to exclude Blacks from participating. In this way, the social boundaries that relegated the incomes and savings of freed Blacks to a separate or “special” banking facility hardened, despite the clear interests and investment Black depositors demonstrated throughout the Freedmen Bank’s short-lived history. Taken together, Douglass, Washington, and Du Bois’ statements demonstrate that despite being treated like financial sheep led into the slaughter, Black people had their own economic savvy and sought ways to make the best of a difficult situation.

As has been shown, the Freedmen’s Bank was supposedly an effort by “the northern friends of the Negro to find a means of elevating the newly emancipated race which would train its members in habits of thrift and economy, and which, by encouraging them to save their earnings, would aid them in securing a stronger economic position in the social order.”28 Despite professed good intentions, racism was still at play. By lending the money of Black depositors to Whites with little to no stake in the bank, the risks inherent in lending and loan repayment were not even distributed. Instead, Black depositors, like Frederick Douglass and many others, shouldered the risks. This process, then, allowed for Whites to unfairly benefit from Black wealth accumulation and savings, even as mainstream banks continued to exclude Black participation.

Further, the sudden shift in management from predominantly White to Black also indicates the structural changes that further facilitated this outcome. As this story demonstrates, Black trust was initially abundant but following shifts in the 1870s by the bank’s White management and Congress, such trust along with the reputation of White-managed banks took a serious hit. Alongside the emergence of this distrust has been a consistent Black avoidance of risky assets specifically (i.e., stocks and bonds) and banks more generally.

The Road to Economic Reparations

As we near the 155th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation, the lessons of that era remain potent. The politics of Black economics should not be viewed only through the eyes of the current context because they have deep roots in the period of Reconstruction. Indeed, as we continue to carve a path through the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis and growing racial disparities in wealth, the history of the Freedmen’s Bank can serve as an important reminder of the connection between financial and political freedom and mobility and damage done to Black wealth and confidence long before banks where too-big-to-fail and subprime mortgages where selling like hotcakes.

Current reparations debates, strategies, and campaigns have pointed to the importance of economic policies to promote racial healing and transformation. For example, Hamilton and Darity advocate a “baby bond” strategy, whereby when Black babies are born a trust is established accruing interest; at age 18 eligible Black youth would then have access to such funds that could then be used, for example, to afford college, start a small business, and/or buy a home.29 Furthermore, recent campaigns have also emphasized the importance of government-funded programs that would advance and enhance Black financial literacy and livelihoods.

This article joins in this growing directive towards economic reparations for the descendants of formerly enslaved Black Americans. It also adds to the calculation of what was stolen, and what is owed, the millions of dollars that were lost in the Freedmen’s Bank experiment. Whereas some existing reparations claims rely on issues including General Sherman’s “Forty Acres and a Mule” promise in Special Order No. 15, restrictive covenants, redlining, and racial biases in labor, this article expands this dialog by centering the important history of a living and ongoing actual debt owed to Black Americans.30

To be sure, the estimates presented in the article thus far offer only a conservative estimate, as the full range of the relative value of the $3,299,201 in 1874 reaches to $7,510,000,000 in 2018 dollars as an economic share of GDP; thus the Freedmen’s Bank episode demonstrates that on just this one site of state failure during Black Reconstruction access to advocate the repayment of a debt of upwards of 7.5 billion dollars can be accounted for and put on the table; such funds could be allocated in ways that would go a long way toward addressing issues of intergenerational wealth, access to and affordability of homeownership and higher education, and Black entrepreneurship. This assessment of the Freedmen’s Bank demonstrates that there are at least four major demands to be integrated into the reparations agenda: (1) Pay back the descendants of the Freedmen’s Bank’s depositors, (2) Congressional apology for the mismanagement of Black money, (3) teach and include the Freedmen’s Bank in our classrooms and textbooks, and (4) an annual earmark in the federal budget of several billion dollars to explicitly target key financial racial disparities in wealth, stock market participation, and educational attainment.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks and acknowledges Aldon Morris, Mary Pattillo, Charles Camic, Cathy J. Cohen, Jean Beaman, Johnathan Holloway, Elizabeth Alexander, Rashida Z. Shaw, Mikaela Rabinowitz, Zandria Robinson, Christopher Wildeman, Gary Alan Fine, Dant’e Taylor, Elijah Anderson, Gerald Jaynes, and Courtney Patterson for their encouraging and constructive feedback.

Funding

The research presented in this article benefited from the generous financial support of the American Sociological Association’s Minority Fellowship Program, the National Science Foundation (Grant ID #0902399), the Social Science Research Council, the Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship Foundation, and the Mellon-Mays Undergraduate Fellowship Program.

WORKS CITED

1. W. E. B. DuBois, The Philadelphia Negro (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1899).

2. All figures reported according to current standards are based on the 2018 Consumer Price Index (CPI). The CPI is especially useful because I focus on Black Americans as consumers. Using CPI, I have produced estimates for all figures to facilitate an idea of how much money was involved in the Freedmen’s Bank and its branches. For more see, Samuel H. Williamson, “Seven Ways to Compute the relative Values of a U.S. Dollar Amount, 1774 to Present,” (Measuring Worth, 2011), http://measuringworth.com/uscompare/.

3. See Arnett G. Lindsay, “The Negro in Banking,” Journal of Negro History 14, no. 2 (1929): 172; for further discussion on Black banks, see also Lila Ammons, “The Evolution of Black-Owned Banks in the United States between the 1880s and 1990s,” Journal of Black Studies 26, no. 4 (1996): 467–89; Abram L. Harris, The Negro as Capitalist (New York: Negro Universities Press, [1936] 1969); Edward D. Irons, “Black Banking—Problems and Prospects,” Journal of Finance 26, no. 2 (1971): 407–25; and Andrew F. Brimmer, “The Black Banks: An Assessment of Performance and Prospects, Journal of Finance 26, no. 2 (1971): 379–405; DuBois, The Philadelphia Negro; Carl R. Osthaus, Freedmen, Philanthropy, and Fraud: A History of the Freedman’s Savings Bank (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1976); and Marcus Anthony Hunter, Black Citymakers: How The Philadelphia Negro Changed Urban America (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013).

4. Walter L. Fleming, The Freedmen’s Savings Bank: A Chapter in the Economic History of the Negro Race (Westport: Negro Universities Press, 1970), 19; see also Ira Berlin, et al., Free At Last: A Documentary History of Slavery, Freedom, and the Civil War (New York: New Press, 1992); Orlando Patterson, Rituals of Blood: Consequences of Slavery in Two America Centuries (New York: Basic Civitas, 1998).

5. U.S. Senate, 46th Cong., 2nd sess., 1880, Rep. 440; U.S. Senate, The Freedman’s Bank Bill, 46th Cong., 3rd sess., 1881; U.S. Senate, 62nd Cong., 2nd Session, 1912, Rep. 759, 4; Walter L. Fleming, The Freedmen’s Savings Bank: A Chapter in the Economic History of the Negro Race (Westport, CT: Negro Universities Press, 1927); Osthaus, Freedmen, Philanthropy, and Fraud.

6. Lindsay, “The Negro in Banking,” 163; U.S. Senate, 46th Cong., 2nd sess., 1880, Rep. 440.

7. Fleming, The Freedmen’s Savings Bank, 26; see, e.g. Congressional Globe, 38th Cong., 2nd sess., 1865, pt. I & pt. II.

8. Fleming, The Freedmen’s Savings Bank, 35.

9. Fleming, The Freedmen’s Savings Bank, 44; Osthaus, Freedmen, Philanthropy, and Fraud.

10. Fleming, The Freedmen’s Savings Bank, 44; Osthaus, Freedmen, Philanthropy, and Fraud; Hunter 2013; U.S. Senate, 46th Cong., 2nd sess., 1880, Rep. 440; U.S. Senate, The Freedman’s Bank Bill, 46th Cong., 3rd sess., 1881; U.S. Senate, 62nd Cong., 2nd Session, 1912, Rep. 759, 4.

11. Fleming, The Freedmen’s Savings Bank, 45.

12. Viviana Zelizer, “The Special Meaning of Money: ‘Special Monies,’” American Journal of Sociology 95, no. 2 (1989): 342–47. Further explaining this concept, Zelizer asserts, “For instance, a housewife’s pin money or her allowance is treated differently from a wage or a salary, and each surely differs from a child’s allowance. Or a lottery winning is marked as a different kind of money from an ordinary paycheck. The money we obtain as compensation for an accident is not quite the same as the royalties from a book” (343). Further discussion in this regard includes: Viviana Zelizer, “Human Values and the Market: The Case of Life Insurance and Death in 19th-Century America,” American Journal of Sociology 84, no. 3 (1978): 591–610; Zelizer, The Social Meaning of Money (New York: Basic Books, 1994); Viviana Zelizer, Morals and Markets: The Development of Life Insurance in the United States (New York: Columbia University); Thomas Crump, The Phenomenon of Money (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1981); Albert O. Hirschman, Rival Views of Market Society (New York: Viking, 1986); and Georg Simmel, The Philosophy of Money, trans. Tom Bottomore and David Frisby (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1900). See also Bruce Carruthers and Wendy Espeland, “Money, Meaning, and Morality,” American Behavioral Science 41 (1998): 1384–88; Frederick F. Wherry, "The Social Characterizations of Price: The Fool, the Faithful, the Frivolous, and the Frugal," Sociological Theory 26, no. 4 (2008): 363–79; and Lisa A. Keister, “Financial Markets, Money, and Banking,” Annual Review of Sociology 28 (2002), 39–61.

13. Osthaus, Freedmen, Philanthropy, and Fraud, 82.

14. U.S. Senate, 46th Cong., 2nd sess., 1880, Rep. 440; U.S. Senate, The Freedman’s Bank Bill, 46th Cong., 3rd sess., 1881; U.S. Senate, 62nd Cong., 2nd Session, 1912, Rep. 759, 4; Lindsay, “The Negro in Banking”; Harris, The Negro as Capitalist.

15. Fleming, The Freedmen’s Savings Bank, 42.

16. U.S. Senate, 46th Cong., 2nd sess., 1880, Rep. 440; U.S. Senate, The Freedman’s Bank Bill, 46th Cong., 3rd sess., 1881; U.S. Senate, 62nd Cong., 2nd Session, 1912, Rep. 759, 4; Congressional Globe, 38th Cong., 2nd sess., 1865, pt. I & pt. II; Lindsay, “The Negro in Banking”; Harris, The Negro as Capitalist.

17. Fleming, The Freedmen’s Savings Bank.

18. Congressional Globe, 38th Cong., 2nd sess., 1865, pt. I & pt. II; Frederick Douglass and Rayford Whittingham Logan, The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (Courier Corporation, [1881] 2003).

19. Douglass and Logan, The Life and Times; Harris, The Negro as Capitalist.

20. Douglass and Logan, The Life and Times, 413–14.

21. Ibid., 410–11.

22. Philip S. Foner, ed., Frederick Douglass: Selected Speeches and Writings (Chicago: Lawrence Hill, 1999): 680–681.

23. Douglass and Logan, The Life and Times, 414.

24. Ibid.

25. U.S. Senate, 46th Cong., 2nd sess., 1880, Rep. 440; U.S. Senate, The Freedman’s Bank Bill, 46th Cong., 3rd sess., 1881; U.S. Senate, 62nd Cong., 2nd Session, 1912, Rep. 759, 4; Fleming, The Freedmen’s Savings Bank; Harris, The Negro as Capitalist; Osthaus, Freedmen, Philanthropy, and Fraud; Interview with the Senate Committee on Finance, April 24, 1888, Frederick Douglass Papers, “Speech, Article and Book Files,” Library of Congress, U.S. Govt.

26. Foner, Frederick Douglass, 680–81.

27. W. E. B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black folk (New York: Penguin Press 1982, emphasis added), 32; Du Bois, The Philadelphia Negro.

28. Fleming, The Freedmen’s Savings Bank, 1.

29. Darrick Hamilton and William Darity Jr., “Can ‘Baby Bonds’ Eliminate the Racial Wealth Gap in Putative Post-Racial America?” The Review of Black Political Economy 37, no. 3–4 (2010), 207–216; see also Mariame Kaba, “Reparations NOW,” http://www.usprisonculture. com/blog/tag/reparations/ (accessed April 7, 2016).

30. This dialog has produced a robust and dynamic number of platforms for reparations claims-making. For further thoughtful analysis see Manning Marable, “In Defense of Black Reparations,” The Freedom and Justice Courier 9 (2002), 2002–10; Manning Marable, “An Idea Whose Time Has Come,” Newsweek, 138, no. 9 (2001), 22; Manning Marable, “The Political and Theoretical Contexts of the Changing Racial Terrain,” Souls 4, no. 3 (2002), 1–16; Alfred L. Brophy, “The Cultural War over Reparations for Slavery,” DePaul Law Review 53 (2003), 1181; Ta-Nehisi Coates, “The Case for Reparations,” The Atlantic 5, no. 5 (2014): 1–62.

Past Editions

1.

A Human Right to Reparations: Black People against Police Torture and the Roots of the 2015 Chicago Reparations Ordinance

Toussaint Losier

2.

Building the World We Want to See: A Herstory of Sista II Sista and the Struggle against State and Interpersonal Violence

Nicole A. Burrowes

3.

Editor’s Note

Barbara Ransby & Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor

4.

Review of Development Drowned and Reborn: The Blues and Bourbon Restorations in Post-Katrina New Orleans, by Clyde Woods

Bedour Alagraa

5.

Seven Billion Reasons for Reparations

Marcus Anthony Hunter

6.

States of Security, Democracy’s Sanctuary, and Captive Maternals in Brazil and the United States

Joy James & Jaime Amparo Alves

7.

We Who Were Slaves

Anthony Bogues