I won’t be interrupted! I don’t tolerate interruptions in this house! [I] won’t tolerate a citizen that comes here and can’t listen to an ELECTED woman!

—Marielle Franco1

Democracy’s centuries-old battles with black captive maternals2 turn deadly when black women claim their rights to power on behalf of the impoverished and the militant seeking an anti-racist commons. Liberal democracy’s evolutionary trek has routinely faltered regarding justice, economic decency, and respect for black lives. The racialized regime of rights that governs the two largest democracies in the continent—Brazil and the United States—hosts the largest concentrations of people of African descent. Although they created national wealth, blacks remain marginalized or excluded in both nations through electoral politics and legal decrees, economic deprivation, and police terror. Within these contexts, policing black bodies strengthens predatory democracies in which the United States leads in mass incarceration, and Brazil dominates in police brutality. Controlling large populations of people of African descent requires repressive policing and incarceration, and occasionally, an occasional political assassination, exhaustion, and trauma that exacerbate mortality rates among activists.

The 2018 murder of Marielle Franco, in Brazil, and 2017 heart failure of Erica Garner, in the United States, exemplify the vulnerabilities of captive maternals as black activist mothers within liberal democracy and predatory capitalism.3 From different nations, and different languages, both mothers led activism to curb extrajudicial killings, torture, and imprisonment. They provided leadership to protect and sustain black communities amid political gaming in democracy. Their tireless efforts, and sacrifices, indicate that the Americas’ two largest democracies, with a history of political assassinations and racial terror, require transnational activism and solidarity to create national and supranational black sanctuaries within violent security states.

Given the current presidential administrations in Brazil and the United States, rhetoric and practices of racial supremacy and violence are increasingly explicit.4 Notwithstanding the scandal around the perhaps brutally honest rhetoric of racial violence that marks the current presidential turns in Brazil and the United States, Presidents Michael Temer’s and Donald Trump’s assaults on black dignity are not original to them; rather, such assaults are located within a long-standing process of black evisceration, embraced also by democratic, liberal presidents. The United States’s first black president, Barack Obama, and Brazil’s first female president, Dilma Rousseff, both embodied the triumphal narratives of liberal democracy as a future with a promissory inclusive commons. Both Rousseff and Obama’s Democratic party nominee Hillary Clinton, who was to uphold Obama’s legacy, were defeated in 2016 after years of failing to wage a battle to end anti-black police terror and mass incarceration. Each was replaced by racist, reactionary white male capitalists who relished publicly the dismantling of civil and human rights with an “iron fist” of state power. Since 2016, the Trump administration has attacked the UN human rights system; engaged in climate change denial; and expressed sympathy towards white nationalists, neo-Nazis, and fascists. He also sought to criminalize women’s reproductive rights and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer rights; deployed Immigration Customs and Enforcement against immigrants; and removed children from parents, reenacting the trauma of child trafficking. The degradations of already severely diminished civil rights are tethered to suppressing voting rights, mass incarceration (waged in the United States during Nixon’s campaigns against black radicalism and anti-imperialism in the guise of a “war on drugs”5), crony capitalism, and organized crime (reflected in the August 2018 convictions of Trump campaign manager Paul Manafort and attorney Michael Cohen).

Brazil’s aspirations for Americana came into full display when Trump’s election was cheered as a turning point to free the continent from the leftist “communist” and “authoritarian” regimes personified in past presidencies of Rousseff’s predecessor Lula da Silva, Cuba’s Fidel Castro, and Venezuela’s Hugo Chavez. The national elite saw in Trump’s ascension to power the possibility for both nations to realign themselves under common interests to forge a state of security, expand militarism, and restructure the flow of capital. Temer replaced Dilma Rousseff, ousted in 2016 by a coalition of evangelicals and investors; he subsequently reversed the Workers’ Party’s social programs and imposed neoliberal policies adversely affecting millions of Brazilians. Temer realigned Brazil to U.S. strategic interests, particularly in energy and defense.

The rise of Trump and Temer led to intense concern among progressive forces about a supposedly “endangered democracy.” The rumors of Russian involvement in the U.S. election and Michel Temer’s authorization of army control of Rio de Janeiro’s public safety spiked protests against the supposedly in-place and now even more endangered democratic state of rights. Temer authorized army control of Rio de Janeiro’s public safety, and sought to open Brazilian territory to U.S. military bases. Mostly white middle-class Brazilian activists saw the presidential decree as aggression against democracy while black activists reminded them that daily checkpoints, arbitrary arrests, collective warrants, shots from helicopters, killings, and disappearances stripped blacks of democratic rights. Human rights and civil rights advocates rightly fear the rise of rightists in Brazil and the United States. Yet, during liberal democratic–leaning administrations, roadblocks to paths towards universal civil and human rights were the norm.

When the conservative white, male, evangelical-led parliamentary, judiciary, media seized power from Rousseff, the Obama administration might have viewed the Brazilian “parliamentary coup” as an opportunity to tame left-leaning nations in South America. During his March 23, 2016, trip to Argentina, at the time of Brazil’s political turmoil, President Obama stated that “Brazil has a mature democracy, with a strong system that will allow it to prosper and be the leader that we need.”6 Less than one month after Rousseff was impeached, Vice President Joe Biden met with new Brazilian President Temer to reaffirm mutual commitment for both nations to “work together to promote good governance, security, and prosperity throughout the hemisphere.”7 Despite the U.S. support, failing to secure popular approval and legitimacy for his neoliberal policies, Temer distracted public opinion by evoking security threats to deploy the Brazilian army to “pacify” black urban centers in Rio de Janeiro. He did so under penal legislation proposed by President Rousseff who authorized the Brazilian military to police Rio during the 2014 World Cup. The ideological and ethical differences between Presidents Rousseff and Temer, and Obama and Trump, are noteworthy. However, presidential revolts in both nations reveal affinities with or tolerance for white nationalism and repressive policing. Obama’s and Rousseff’s administrations were marked by police aggression disproportionately impacting the sexualized, racialized, and gendered urban poor.

Some scholars have identified the backlash to left-leaning governance in the Americas as the result of the Left’s failure to articulate broad, identity-based demands for social justice and provide radical alternatives to predatory capitalism.8 Legalized and extra-legal forms of repression and terror situate the emergence of racist–authoritarian-leaning politicians within shifts in regional racial formations after a three-decades-long implementation of multicultural policies marked by the consolidation of corporate power and aggression against black and indigenous territories; state retreat from affirmative action and distributive policies; rise of patriarchal values; and criminalization of (identity-based) social movements.9

The end of Brazil’s timidly inclusionary democracy (with the defeat of the Workers’ Party) and the United States’s “post-racial” era under and after Obama reflect such shifts. The exceptionalism of Obama, as the first U.S. black president, and Rousseff, as the first female Brazilian president—Rousseff is also a former Marxist revolutionary, tortured and imprisoned by a dictatorship the United States helped to install in the early 1960s—were symbolic and represented popular aspirations. Yet both singular presidencies failed in transformative ambitions because their vision did not challenge the anti-black structures within liberal democracy. Anti-black democracy is where the racially charged Trump and Temer administrations and the integrationist narratives of Obama as the first black U.S. president and the racially inclusive language of Brazilian Presidents Luiz Lula da Silva and his prot,eg,e Rousseff meet. During the Obama presidency, the United States rhetorically moved beyond “race.” During the 2016 presidential election and aftermath, the Trump administration moved back towards “race” to embrace white nationalism and assaults on civil and human rights. In both administrations, narratives about racial–gender inequality were situated as the product of personal economic and moral failures rather than racist–capitalist structures.

Neither liberals nor reactionaries challenged the ideologies and practices that sustain empire as a racial project. Trump campaigned to “Make America Great Again” as a restoration of whiteness sullied by unlawful and unworthy colored immigrants, and a president of the United States whom Trump vilified through “birthism” as an unworthy, colored immigrant. Obama campaigned for his surrogate Hillary Clinton in 2016 by stating that America was already “great.” No presidential discourse (outside of that of insurgent Bernie Sanders who primaried against Clinton and endorsed her in the 2016 general election) presented predatory capitalism, the imperial wars, and police repression as structural flaws that disqualified claims to greatness.

Lula da Silva’s and Rousseff’s governments promoted racial inclusion programs along with the ideology of multi-racial democracy, yet ignored community activists’ assertions that black genocide was structured and waged by police, paramilitary, and corporate violence throughout Brazil. As police terror and homicides in Brazil indicate, the paradox of granting some rights and denying life itself was never structurally addressed by liberals or progressives.10

Nostalgia for the presidencies of Obama and Rousseff is predictable and expected. The civility, optimism, and the rhetorical embrace for liberal values were clearly visible in those administrations. Still, the avoidance of facing capitalism and white supremacy as foundations for predatory democracies meant the missed opportunity for structural liabilities as U.S. “national greatness” and the Brazilian “passport to the future” served as marketing campaigns masking perilous times. It is true that those liberal-centrist governments lacked the vulgarities of the Trump and Temer coalitions that boldly seek the restoration of unapologetic materialism and robber-baron capitalism based on heteronormative, Christian, white, patriarchal, propertied status. The lack of a “Marshall plan” for exploited and denigrated peoples historically hounded by the state and its police is found in both liberal and reactionary regimes. By the time the 2016 Brazilian parliamentary coup and Trump election occurred, their abilities to “threaten” liberal democracy were enhanced by the inabilities of liberal democrats to accurately provide the terra firma to challenge the basis upon which Temer/Trump’s rhetoric rested: a fault line riven by global capital, monied interests in elections, the rise of paramilitary and right-wing factions, inflamed racial animus, sexual predatory behavior, and control of women and queer communities. In all these instances, the real “threat” to democracy was the African-descent, brown, and indigenous people in Brazil and the United States, who would need to be subjugated or expunged.

From the hard-core racists, or “alt-right” and neo-Nazis, to the anti-racists, one could identify at least three current ideological fields filtered through gender, sexuality, and class politics: (1) “hard” racists or fascists; (2) “soft” racists; and (3) anti-racist structuralists or radicals. Anti-blackness would be central to the first category populated by rightists and pro-authoritarian factions; liberals embraced the second category with the “deficiency models” of behavior attributed to poor people and people of color as the largely agentic deficient wards of the state or professional caretakers. The third category of intellectuals and activists who insisted upon structural critiques of capital and hetero-fascist white supremacy by which those most impacted by violence co-led movements (e.g., the imprisoned activists on strike August 21–September 9, 2018) gained little traction under liberal regimes and were viewed as the primary “enemy” by reactionaries.

The third category of analysis, radical critiques through anti-racist structuralism, views democracy as inherently flawed because it was built on enslavement and genocide, and endangered by national leaders’ refusals to confront its contradictions. The trajectory and historical continuum of democracy in Brazil and the United States stabilize rather than rupture the notion of the commons. The “shift” in the current racial order is a readjustment of route—after some minor bumps (civil rights movements and voting rights are under assault), given the synergy between democracy and police terror.11

The sister-relationship between Brazil and the United States and their respective and shared democratic “crises” elicit some propositions: (1) reactionary elected regimes are a threat to liberal democracy, yet, at their core, those regimes share with liberalism structural exclusion of black participation in the commons; (2) U.S. white nationalists and heterosexists reflect American “core values” just as Brazilian white elites’ seizure of power recalibrates racial–sexual hierarchies; (3) anti-black police terror is foundational to the rule of law by which racial democracy prevails. Liberation activism and intellectualism must exceed the capacity of democratic electoral politics, civil rights, and conventional legalism in gaming. The rise of authoritarian and racist regimes in the United States and Brazil is countered with challenges to liberal democracy’s anti-black, anti-indigenous, gendered, and monetized policies.

On June 30, 2015, President Dilma Rousseff visited President Barack Obama to sign agreements on energy, climate change, trade, education, and security. Flirting with Brazil’s ambition to have a permanent seat on the UN Security Council and to become a global player in clean energy and anti-terrorism, Obama welcomed Rousseff and highlighted the shared democratic and human rights values of both nations. They signed the United States-Brazil Defense Cooperation Agreement, which aimed at boosting the defense industry and promoting military training and international peacekeeping operations between the two countries.12 In addition to increasing the militarization of the continent, the U.S.–Brazilian joint effort in security strengthened their domestic racial orders.

To celebrate the exchange of military technology, Obama–Rousseff’s international diplomacy shadowed the memorial of Dr. Martin Luther King in Washington, D.C. There, both presidents adhered to peaceful civil rights protests and expressed solidarity with demonstrators protesting police violence. Yet both governments failed to curb lethal and excessive police force that targeted black and brown people within nations providing security for propertied whites through homeland security and militarization of urban policing. (Obama in fact had stated in 2015 after the Baltimore rebellions and riots following the police homicide of Freddie Gray that he could not “federalize” or control local and state police.)

With diverging backgrounds that made them seem even more remarkable, Rousseff and Obama presided over administrations that embodied symbolic politics insufficient to structurally assist poor and working-class policed communities.

Despite the tensions between the two former administrations—the White House spied on Brazil’s strategic mineral resources and Rousseff’s electronic communication—both governments strengthened joint efforts to promote “democracy and stability” in the Americas through the further militarization of the continent and the further militarization of homeland security. Both worked in the 2010 military–humanitarian intervention in Haiti where the Brazilian army conducted urban policing. Both launched the OBANGAME EXPRESS program, created to counteract terrorism and piracy in the hemisphere. The U.S. Army trained at the Brazilian Army’s Instruction Center for Jungle Warfare. Both nations deployed local military forces on the coast of Africa. At Brazil’s Superior War College, in April 2012, U.S. Defense Secretary Leon Panetta asserted a “shared vision of deeper defense cooperation that advances peace and security in the 21st century.” Mr. Palleta also highlighted Brazil–U.S. historic connections to Africa and joint interests in stabilizing the continent.13

Defense contracts between both nations increased during the Obama–Rousseff administrations. As a strategic market, Brazil's National Defense Strategy was launched by Lula da Silva in 2008, increasing business opportunities to the United States. The Brazilian Ministry of Defense reported that between 2010–2012 the imports of U.S. defense equipment (U$1.1 billion) totaled nearly half of all Brazilian defense trade (U$2.4billion). Under U.S. influence, Brazil established military cooperation also with Israel, the U.S. Department of Defense’s close ally in security technology.14 The Brazilian army signed a protocol for technology with its Israeli counterpart and mercenaries Blackwater (renamed XE Services in 2009), the key military contractor during the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, trained Brazilian police in a highly controversial U$2 million contract with the U.S. embassy.15 U.S. and Israeli military technology increased Brazilian state capability to police black Brazilians while selling its image as “soft” humanitarian power abroad.

The respective successors of each president seek to dismantle progressive legacies. And yet the progress in “progressive” was never fundamentally opposed to capitalism, white supremacy, or hetero-patriarchy. Bourgeois democracies grant ideological cover for the concentration of police and military power at home and abroad. Progressives and liberals in both democracies express a nostalgia for these former administrations as a counter to the authoritarian norms set by Temer and Trump. It is difficult for some to contemplate that liberals and authoritarians exist on the same ideological continuum: liberal and reactionary leaders oversaw the increasing concentration of capital and expanding militarization of repressive policing.

Policing black bodies at home and waging wars against racialized enemies abroad are aspects of protecting white life and wealth. Empire as racially driving domestic U.S. policing fuels geopolitical interests.16 For instance, lynching and torture deployed against racial minorities in the United States resonates in counterinsurgency and death squad practices in Brazil and Latin America.17 The U.S. School of the Americas (SOA), renamed the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation, is a training ground for state terrorists in the region. The SOA was known among human rights activists as the “School of the Assassins” for its role in training death squads in El Salvador and Guatemala during the cold war to undermine communist guerrillas. SOA’s militarized violence sparked racist violence against indigenous, black people, unionists, and human rights advocates. SOA’s goal to “secure” U.S. multinational corporations by supporting murderous political regimes in the region targeted black and indigenous communities with counter-insurgency forces, creating the genocide against the Mayans in Central America and facilitating assassinations of activists in Colombia.18

In Brazil, this transnational regime of terror is tested on the bodies of black youth. With one of the most brutal police forces in the world, in 2017 alone at least 4,122 individuals were killed in this country, an average of twelve deaths per day. Between 2009–2013, the police killed 11,197 persons. Police forces are responsible for 15.5% and 20% of homicides in Rio de Janeiro and S~ao Paulo. Young black males constitute 79% of Rio’s and 60% of S~ao Paulo’s victims of police lethal violence.19

In the United States, police killings are poorly documented because the police are not required to keep and maintain accurate records. The Wall Street Journal (WSJ), for instance, documented 550 homicides by the police that went uncounted by local law enforcement agencies throughout the United States between 2007–2012. During that period, WSJ found underreported cases of “justified killings” by the police in at least 105 U.S. police departments. Disparities were attributed to corruption, lack of accountability, coding problems, and poor record systems. One example is the Ferguson Police Department in Missouri where the WSJ found that in 35 years (1976–2012), local law enforcement reported only one case of killings by the police to the Federal Bureau of Investigation; however, black community leaders document a systemic culture of killings by Ferguson police.20

Comparisons to Brazil might lead some to surmise that U.S. policing has a superior human rights record than other democracies’ treatment of the African diaspora. Yet, compared to other “advanced democracies,” the United States is a frontrunner in the killings and hyper-incarceration of black men, women, and children (Brazil increasingly is becoming its competitor). With six times the population of the United Kingdom, U.S. police killed the same number of individuals (59) in one month in 2015 that the UK police killed in twenty-four years. Germany registered 15 killings by the police between 2013–2014, the same number of unarmed black men fatally shot by the U.S. police during the first five months of 2015.21

The increasing militarization of U.S. domestic policing has been denounced by international agencies. The 2014 Amnesty International campaign “Bringing Human Rights Home” denounced the systematic torture of more than 100 individuals between 1972 and 1991 by police in Chicago, Illinois (the home city of the Obamas). The detectives used electric shock boxes and plastic bags to suffocate suspects and to obtain confessions for crimes they did not commit.22 The “nigger box,” as the electric shock box was known, was supposedly abandoned in 1992, but on February 15, 2015, the Guardian revealed an “off-the-books interrogation compound that lawyers say is the domestic equivalent of a CIA black site.” According to journalists, the interrogation site reproduces the same tactics used by the United States in its war against terror; these tactics closely resemble practices deployed in Abu Ghraib and Guant,anamo; civil rights activist Tracy Siska states that the war on terror “creep[s] into domestic law enforcement, either with weaponry like with the militarization of police, or interrogation practices. That’s how we ended up with a black site in Chicago.”23

Often police brutality is framed in mainstream critiques as a bad cop’s pathological behavior. Likewise, progressive social movements denounce police violence as an institutional deviation, incompatible with democracy. In the case of Brazil, the main argument on the Left is that police violence is the result of dysfunctional institutions of control that have been corrupted during the military dictatorships. Individual misconduct is driven by the legacies of the authoritarian period that continues to inform social relations. Likewise, in the United States, although officers are rarely found guilty, the prescription to end pervasive police terror is providing better training, promoting racial and gender diversity in troops, and punishing wrongdoings. In some accounts, aggressive policing is fine, insofar as it does not exceed its legal boundaries against “innocents,” unarmed civilians. Scholarly and activist contextualization of police violence within the larger political and ideological context of popular support for tough penal policies, a widespread culture of authoritarianism and pervasive “institutional failure” to control the police, is valuable.24 Still, the reliance on “democratic” institutions to curb police violence overlooks antagonistic structures and differential powers that render some lives stripped of state protection: black communities are not permitted to control the police that prey upon them while “serving” them. The logic of policing is a logic of terror and enmity. This logic is not counterintuitive or dysfunctional to the game of democracy; quite the opposite, democracy and police terror dialectically produces white civil life and black (social) death.25 In the U.S. “land of the brave” and Brazil home of the “cordial men,” ghettos and favelas are those expanded zones of death and predation where democracy is better defined as a permanent state of emergency.

On February 6, 2015, days before carnival, the Military Police killed thirteen young black men in Cabula, a poverty-stricken, predominantly black neighborhood on the outskirts of Salvador/Bahia. The police claimed that responding to an anonymous tip about a bank robbery they encountered “criminals” who fired at them. Police shot sixteen youths, killing thirteen and injuring three. The massacre took place under the leftist Workers’ Party’s administration, which replaced a twentyfive-year turn of a repressive right-wing coalition led by power-broker Antonio Carlos Magalh~aes. Officers responsible for the massacre were applauded by mainstream media and regarded by the governor as heroes. The leftist governor, Rui Costa, celebrated the police raid with a football metaphor: “Like a forward player in front of the goal, the police have to decide in seconds, how to score … if an officer scores he will be applauded, if he misses the goal he will be criticized.” Costa also reassured a cheering police audience during a public speech that there would be no legal action against the killers because “there is no evidence that indicates an unlawful action in this case.”26

Raquel Luciana de Souza’s 2017 analysis of the massacre meticulously documents how favela residents carried out their own investigations revealing a very different story: Those killed did not fire at the police. They were young black men gathered together on a soccer field. After executing them, the police replaced their clothing with military uniforms yet failed to cover up the evidence of a mass murder, leaving behind t-shirts and other clothing riddled with bullets holes and soaked with blood. They took pictures of the bodies lying in the corridor of the hospital and distributed them to social media. Later, at a news conference, they displayed photos of guns, drugs, and a few hundred Brazilian reais they claimed were seized during the raid.27

When community organizers denounced the “orchestrated genocide of black people,” the governor and his assistants insisted that the police would deploy full force, as needed, to protect the “good citizens” and that the government was “just responding to the threat” posed by bandits. Within the Brazilian deadly mode of racial relations, “bandit” is a racially coded word for young black males from impoverished urban communities. Vilma Reis, a leader in the Brazilian black movement, explains how this racial common sense plays out in Salvador’s urban periphery: “The police treat the black and poor population as enemies. … [It’s a] war against blacks.” Reis denounces that while the state fails to provide citizenship rights for black people, it is diligent in deploying the police against racialized communities: “the police should be the last resource to arrive, [yet] they are the first and most of the time the only ones.”28 Being “enemies,” blacks could not occupy public space to protest police terror without inviting further violence. In response to the Cabula Massacre, favelados set fires on buses and blocked main streets to call attention to police terror. Police terrorized protesters, yet activists persisted; one relative of the slain stated: “[Police] came angry, beating up everybody … slapping in the face, but we will not shut up. That was just the first of other protests that will come.”29

Similar to Afro-Brazilians, African Americans are also regarded as enemies of the state and civil society. Although rarely articulated in the discourses of liberals, (para)military violence inflicted by police on civilians and political dissidents has long been part of the U.S. domestic security strategy. During the Obama administration, government responses to urban riots in Ferguson and Baltimore (in 2014 and 2015, respectively) prove this point. Like most of disenfranchized urban Black America, these two U.S. cities have long been police-controlled territories that although familiar to many, were exposed during the urban unrests following the killings of Michael Brown and Freddie Gray. In Ferguson, Missouri, police killing was part of a larger and systemic practice of state abandonment and everyday violence. For instance, by the time Brown was killed, white unemployment was 5.7%; black unemployment was 17.8%; and 25.3% of the black population was living in poverty.30 Substandard public schools, limited employment for blacks, government use of punitive municipal fees to extort blacks and to fund city payrolls (mostly for whites) … all these ordinary practices turned Ferguson into a depressing antiblack space. The Department of Justice (DOJ) reported that between 2012–2014, 90% of the Ferguson Police Department (FPD) force was deployed against African Americans: “African Americans accounted for 85% of vehicle stops, 90% of citations, and 93% of arrests made by FPD officers, despite comprising only 67% of Ferguson’s population.”31

Similar to Brazil, police relied on the construction of black youth as “enemies of civil society” to justify eighteen-year-old Michael Brown’s death. Officer Darren Wilson argued that the teenager resisted arrest by making “a grunting-like aggravated sound.” According to Wilson, Brown came toward the police patrol, grabbed the door, and hit him in the face; then grabbed his gun and tried to shoot him. The policeman describes Brown as a “really big one” who made him feel like a vulnerable child. In Wilson’s words, “I felt like a five-year-old holding onto Hulk Hogan. That’s just how big he felt and how small I felt just from grasping his arm.” Wilson fired at Brown, but stated that the teenager did not surrender and that he “looked like a demon” as he moved towards the officer. Wilson’s descriptions of the teen’s last moments are justification for homicidal violence: “And the face that he had was looking straight through me, like I wasn’t even there, I wasn’t even anything in his way.”32 Brown’s supra-human body was a threat that justified Wilson’s use of lethal force in self-defense. He did not have to retreat, wait for back up, or not pursue Brown without adequate support that would not entail lethal force. It was his duty as a police officer to “stand his ground” (the same rationale used for George Zimmerman’s homicide of Trayvon Martin in Florida several years earlier is largely ineffectively used by blacks who fire their weapons). The narrative opposing a “real big” black teenager (Brown, 6’4”/300 lbs.) and a “child-like cop” (Wilson, 6’4”/240 lbs.) renders police the victims of irrational, black beasts.

When the November 24, 2014, verdict to not indict Wilson was announced in Ferguson, Louis Head, Brown’s stepfather, entered the camera frame of his sobbing mother Leslie McSpadden to yell “Burn this bitch down!” Protestors responded and the city went into chaos. News anchors condemned Head for inciting violence and Ferguson police threatened to indict him for the riots that followed. Media and police offered little condemnation of the regime of police terror that black Ferguson endured for decades. U.S. police and news commentators used a more sophisticated language about Ferguson than the leftist governor did in the Cabula Massacre in Salvador/Bahia. In the United States, the DOJ investigation noted in its toxicology report that Michael Brown when killed was under the influence of THC, which produces the hallucinogenic properties of marijuana; for some that report indicated that death was justified and that the teenager Brown was not “innocent”; thus, without being the “ideal” victim he could not be victimized at all. Yet activists rejected state mythologies that legalize police terror by making black victims the victimizers of defenseless officers.33 They also rejected the “bad victim” versus “good victim” duality of mainstream protest against policing by dismissing the angelic martyr narrative and by asserting Brown’s right to live regardless of his behavior or legal status.

While Obama could not silence the protests (largely driven by black activists) concerning Ferguson, Brazilian authorities had greater power over censorship. Frustrating human rights activists, Rousseff responded to public protests against the Cabula Massacre with silence. Although the federal administration was not directly involved in the massacre, the “new” slaughter was all but an exception in a modus operandi that intensified under the preparation of mega sporting events. Rousseff,s investment in the militarization of policing was also a domestic replication of the global war on terror. For instance, she sanctioned a set of anti-terrorism laws which expansively defined “terrorism” to criminalize social movements through arbitrary detentions even against her sympathizers. She was the first female president of Brazil who authorized the Brazilian Army to invade and seize black territories in pre–World Cup and pre-Olympics Rio de Janeiro.

Rousseff did condemn police brutality on March 16, 2014, when Claudia Ferreira da Silva, a 38-year-old Afro-Brazilian was shot in the head by a bullet in the crossfire between police and drug traffickers in the favela where she lived with her four children in Rio’s Zona Norte. Bundled into a police patrol car, she fell out in transit to the hospital, was dragged along the way, and pronounced dead at the hospital. The Brazilian president used her Twitter account to say that the nation was “shocked” but made no reference to her government’s direct involvement in Rio’s war against black favelados. Rousseff’s empathy for Claudia’s family “in this moment of pain” stressed Claudia’s innocence as a bystander and highlighted Claudia’s heteronormative, civil status as a good wife and mother: “[She] had four children, was married and used to wake up in the early hours of the morning to go to work in a Rio hospital.” Victims of police terror not seen as “hard-workers,” cisgender, “good” parents, and citizens are left outside of the zone of governmental care.

Like Dilma Rousseff who remained silent while her Party’s governor celebrated the Cabula Massacre as a score against thugs, President Obama initially distanced himself from the police crisis in urban America. During the 2014 Ferguson demonstrations he remained silent. Obama gave a speech condemning the “thugs” in the Baltimore street riots following the police homicide of Freddie Gray on April 28, 2015. Although the president acknowledged the executive branch’s inability to control dangerous practices of police who are not “federalized,” Attorney General Loretta Lynch condemned protestors’ violence against Baltimore police and property. Validating “legitimate peaceful protestors,” she offered DOJ investigations into Freddie Gray’s death and sought a consent decree for police reforms. That push for reform was based on the concern with destruction of property and the maintenance of public order. Before the riots, in 2014, Attorney General Eric Holder’s Department of Justice rejected Baltimore Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake’s and Police Commissioner Anthony Batts’s calls for federal investigations into the Baltimore police (despite The Baltimore Sun’s expos,e on police brutality and racism). The DOJ instead authorized COPS—the president’s Community Oriented Policing Services—as an incentive that would avoid antagonizing the police. Yet the police continued to violate black communities. Nonetheless, during the April 2015 riots, government officials declared that the “Baltimore community” must adhere to “the principles of nonviolence,” a “peace” to be enforced by a police whose violence was protected by bureaucracy structured in unions and laws such as the Baltimore police “Bill of Rights.” Activists disagreed and denounced police “riots” in paddy wagons and streets, and the evaluation of “broken windows” as more important than “broken necks.”

The U.S. press reported that after school 300 students rioted (thousands went home) without noting what teachers, administrators, and students witnessed: militarized riot police forcing students off buses, blocking subway travel, and refusing to let students leave Douglass High School for home. In May, a student’s handwritten missive to alternative press stated that police commandeered their transportation and corralled and intimidated them. Therefore, students reasoned that rather than turn their anger on each other they would turn it against the police. Much like the “gang threat,” media uncritically accepted the predator teen “threat,” increasing sympathy for police. Governor Larry Hogan outlined the military campaign: Baltimore divided into sectors cleared by police and secured by the National Guard. The mayor set a curfew (lifted after police indictments). Underreported by the press, gangs called truces, and the Nation of Islam, black clergy, and community leaders walked the streets as moving shields between rioters/rebels and police and property. Combatants and criminals (conflated into “thugs”) conformed to community and spiritual leadership.

Obama’s condemnation of Baltimore’s youth as “thugs” and Rousseff’s silence on the Cabula Massacre reveal their lethal investment in the anti-black democracy. Both the black and the woman presidents, as commanders in chief of the Americas two largest democracies, oversaw policing apparatuses and were complicit with racially driven police terror. Could they do different under the guise of the democratic regime of rights? Regardless of who is occupying state institutions, police terror and democracy work in tandem.

Exporting surplus military technology to Brazil is part of empire’s racial geopolitics of security. Consider for instance the favela where Claudia Ferreira da Silva lived, in Rio de Janeiro’s hillsides. The community was part of the program of “pacification”—in which U.S. and Israeli military technology was deployed to seize the “enemy’s” territory.34 Although young black men are by far the main victims of this urban warfare, black women’s bodies have been “securitized” as the dangerous site for the reproduction of black criminality. Consider for instance that Rio de Janeiro’s former governor Sergio Cabral’s support of abortion as a preventive measure against urban violence in Brazil was tied to ending “urban violence … [and] an assembly line of delinquency.”35 Although analyses of urban violence barely make connections between geopolitics of empire and domestic policing in Brazil and the United States, black women’s experience renders this continuum manifest. The multiple forms of victimization—military occupation, surveillance of sexuality, psychological pain, rape, targeted assassination, and so on—all comprehend an expansive web of state terrorism that targets the black female body in paradigmatic ways. These racial gendered bodies are sites where domestic and global articulations of power come together in the name of empire-making.36 This diffused and yet concerted assault on the gendered black body also has the (un)attended consequence of obscuring the rationality that informs this anti-black war as well as responses to it: police violence produces multiple forms of suffering and mass perceptions of police violence obscure female victimization.37

The connections between “domestic,” “state,” and transnational forms of violence facilitated or promoted by empire are critical. Legal scholars Kimberle Crenshaw and Andrea Ritchie argue that black women’s subordinate social position “creates the isolating and vulnerable context in which their struggle against police violence, mass incarceration, and economic marginalization occurs.”38 The killings of Sandra Bland and Claudia da Silva invite reflections not only on the liminal position of black women within geopolitics of security, but also on the difficulties to render their fate visible even among progressive forces. In the case of Claudia’s murder, a black female body dragged through city streets was too grotesque to be ignored by the news. However, military occupations of communities, ordinary disappearances, rapes, and psychological traumas are rendered invisible in media and popular discourses. What would be the metric for familiar military raids in favelas and the trauma or posttraumatic stress disorder in their wake?

Sandra Bland’s fate broke the wall of invisibility because of videotape which recorded the traffic stop and altercation before her incarceration. On July 13, 2015, 28-year-old Bland was found dead in a Texas jail cell. The autopsy report indicated that her injuries were consistent with suicide. Bland had been stopped and arrested following a traffic violation of changing lanes without signaling. She was taken into custody and charged with assaulting the arresting officer, Brian Encinia (who was later fired). The video released after her death shows Encinia ordering Bland to put out her cigarette and get out of her car. When she states that she has a right to smoke in her own car and that she has already been ticketed and should be able to proceed, the officer aims a Taser at her and threatens to “light her up” for noncompliance. A bystander filming the arrest was threatened by the police to stop filming. Off-camera one can hear Bland’s screaming and cursing that she is in pain and that her head has been slammed into the ground. A black woman officer who arrives provides no comfort and does not de-escalate the situation but informs Bland that she should have complied with Encinia’s orders and spared herself the pain. During the intake process, Bland indicates that she did not have the funds to post bail; and that she had been suicidal due to a miscarriage; yet she was not placed on suicide watch. Sent to an individual cell with plastic garbage bag liners, Bland was found hung. Police and the coroner ruled that she asphyxiated herself. After Bland’s death, her family and black activists raised doubts about the suicide claim and requested an independent federal investigation to determine if this were a homicide. Her mother, Geneva Reed-Veal, maintains that from the autopsy the state removed and refuses to return parts of her daughter’s throat for burial. In the protests that unfolded after Bland’s death, activists refused the official explanation of suicide and argued that “the system killed her.”39

Other atrocities concerning black female encounters with state terrorism include police rape. Police “justifiable homicide” has no equivalent in “justifiable rape”; thus police protective discourse stigmatizes black female (and queer) sexuality, arguing seductive “consensual sex” or denying the facts altogether. While rapes by officers are endemic in Brazil, rare cases of sexual violence involving police officers rarely break the wall of silence and impunity. When they do so, the victims have to bring their cases to international courts because the timeframe to indictment and trial expires before the state takes action. Illustrative here is the world famous massacre of Alemao, a favela in Rio’s Zona Norte—when thirteen individuals were killed and three teenagers were raped by the Military Police in an October 1994 military operation. After a long battle and legal dismal, the victims decided to bring the case to The Inter-American Court of Human Rights, which condemned Brazil in 2015 for failing to bring the perpetrators to justice even though the events happened twenty years earlier. The police officers argued that the victims planted evidence to criminalize them.40

In Oklahoma City, when police lieutenant Daniel Holtzclaw was charged with raping thirteen women in 2014, he became a high profile example of sexual violence among U.S. police officers. According to the 2010 CATO Institute Report, police sexual misconduct is the second most reported police crime following beatings. Also, a report on black women and police violence indicates that of 546 cases involving police sexual misconduct, between 2007 and 2010, the officers were onduty in 51.3% of the cases and 32.2% of the cases involved rape.41 Indeed, sexual violence is not a peripheral problem in police misconduct. Black male victimization eclipses black female victimization in media and cultural representations; even in rape—which predominately victimizes females—sexual assault against males becomes synonymous with police predation. In 1997, Attorney General Lynch prosecuted white officers who sodomized Haitian immigrant Abner Louima with a toilet plunger in a New York Police Department precinct. This led to the largest New York City settlement for police violence.

How does the black movement respond to these less visible and yet pervasive42 practices of police terror facilitated or energized by geopolitics? The Black Women’s Blueprint rightly argues that mass protests can deflect from police violence against black women and transgender people. Gender bias in the movement masks the intensity and pervasiveness of police sexual assaults as intergenerational. The attack on black females’ reputations for their nonconformity as well as the discourse of “black respectability” constitutes an internal policing that undermines coalitions against police terror; it also further underestimates state and civilian sexual terror against ungendered or nonconforming blacks. This rings true also for Brazil where the silence of the black movement about violence against and the assassinations of black non-cisgender and transgender people reveal the limits of a “radical” male-centric agenda around black victimization. Police killings of black transgender individuals remain a taboo subject in black political protest, even though queered black (i.e., sexually-racially stigmatized) vulnerable populations are the main target of state terrorism.43

The heteronormative category “motherhood” is repurposed by “captive maternals” to reclaim ungendered generative powers to constitute black family, community, and society as a foundation for sanctuaries resisting repression. Sanctuary here means an inclusive, queered movement centered on the protection of black and other vilified lives. Empire forges geographies of security through violence against black communities. An enslaved and/or colonized womb that gives birth to democracy’s prey is also the locus for a unified hemispheric struggle to turn out of a continent sanctuaries securing black lives.

Debora Silva, a leader of Maes de Maio, envisions a transnational network of warriors “fighting with their wombs” to “de-militarize the Americas.” During an international meeting in May 2016, at the City University of New York–Staten Island, with black mothers from Colombia and the United States, Silva denounced the U.S. war on African Americans and identified an imperial affinity between the global war on terror, killings of black youth in the United States, and police terror in Brazil: U.S. taxpayers funded the war at home and abroad. “Your tax-money paid for the bullet that killed my son,” she said to a muted audience. Silva proposed a broad alliance among black mothers to turn the Americas’ imperial geography of policing into a field of political possibilities: “Nobody will stop this movement because this movement is a movement of mothers, women that will demilitarize the police in the Americas. The mothers are ungovernable and will not admit the state determines how long our children will live.”44

The idealized mother of the Christian world becomes a “warrior” that fights the imperial war launched by police and military. Maternal rage becomes the political resource for the dispossessed; the captive black maternal (ungendered) refuses death and defeat despite the inevitability of each.45 Black mothers have embraced the dead as “our” children beyond the criminalizing rhetoric of good victim/bad victim deployed by mainstream media and conservative movements. Relatedly, another strategy has been to “adopt” the forgotten dead as part of the denigrated black community. Mothering and maternal care reclaim the dead to forge community among the grieving and those who struggle. Commenting on Claudia’s death, black activist Thandara Santos related Claudia’s fate to other unknown victims of police violence:

I didn’t know Claudia before. Thinking better … maybe I knew Claudia. Maybe I also knew her children. Let me remember that son of Claudia who was murdered in his doorsteps [sic], here in S~ao Paulo. She had another child that was tied to a pole and beaten. I remember even her husband, who was tortured to death inside a military police station in Rocinha. [I remember also] the daughter of Claudia [who] was raped again inside the police patrol.46

Relating nameless victims of police terror to Claudia’s assassination, activists “adopted” and expanded a politics of resistance that takes maternal encounters with the state and its supranational politics of security as the reference-point to a maternal rebellion against anti-black democracy.

Perhaps black, lesbian mother Marielle Franco’s activist labor better illustrates maternal rage and love in the name of black life. Assassinated on March 14, 2018, Marielle was one of the black activists who stood against “pacification” programs and against military intervention in the favelas.47 Unusual political mobilization across a wide range of social movements and progressive politicians denouncing her assassination indicated that Marielle Franco’s murder was unique as a political assassination in a state attempting to tame ungovernable political protest. She crossed the line, transgressing the spatial and social boundaries expected of black women from favelas. Franco demanded and fought for an antiracist commons that would include Rio’s dispossessed black population as she attempted to decolonize state structures. Her death was a reminder of democracy’s deadly game and a prophetic assertion of black maternal love. When liberals tried to capitalize on her death and discipline the narratives around her, Marielle’s friend Lourenco Silva wrote on Facebook: “The message was to the favela, not to the White leftist and macho [movement] of Rio. The idea was to tell the favelado, be careful, and watch out; there is no space for you here, don’t protest, don’t denounce. Accept!” Existing for centuries outside state domains (in some form of maroon or quilombo communities), black commons have never completely accepted bondage.

Oh, Mary, don’t you weep. Tell Martha not to moan. All of Pharaoh’s army got drowned in the Red Sea one day. —Aretha Franklin, Mary Don’t You Weep, 1972

At the height of the black liberation movement that sparked prison abolitionism, Aretha Franklin, a supporter of the Black Panther Party, retold in song the biblical story of sisters Mary and Martha whose beloved brother Lazarus died in Jesus’s absence. Franklin narrates that Mary ran to Jesus with admonishing grief: if he had been present, Lazarus would still be alive; at the request of their savior, the women brought Jesus to the burial site. There, according to the late, great “Queen of Soul,” Jesus said “For the benefit of you who don’t believe in me this evening, I’m going to call him three times … . He called [“Lazarus”] three times, and Lazarus got up walking like a natural man.”48

Figure 1. Maternal activists Brazilian Debora Silva and U.S.-Chicagoans Dorothy Holmes and Shapearl Welles stand centered beneath a banner in front of a Cali cultural center. The banner inscription translates: “Who feels for our dead? May the mothers’ pain transcend borders.” Photo by Global Network of Mothers in Resistance, Cali, Colombia, September 2018.

No one can definitively state how to “resurrect” democracy as a benign environment for black peoples; nor can we predict if popular armies will voluntarily realign to defend people over concentrated capitalism; or if an anti-racist commons will eventually disrupt white nationalism. Amid our struggles with restorative justice for civilians to diminish or cease inflicting violence on families, communities, and societies, we seek a social order that can deliver the stability and sanity that we deserve. Until the anti-black ethos that founds the state of rights (and legitimizes “the-state-as-master or master-state” narrative)49 is challenged, the “ordinary” killings of blacks in the hemisphere’s two largest democracies will continue to be part of democracy’s game. Perhaps our refusal to continue to play the game within conventional political parties and protocol might usher in greater imagination and organization for a free commons. However, we will never truly comprehend our capacity in political will and imagination unless we cross language and geographical borders to create a transnational alliance among liberationists.

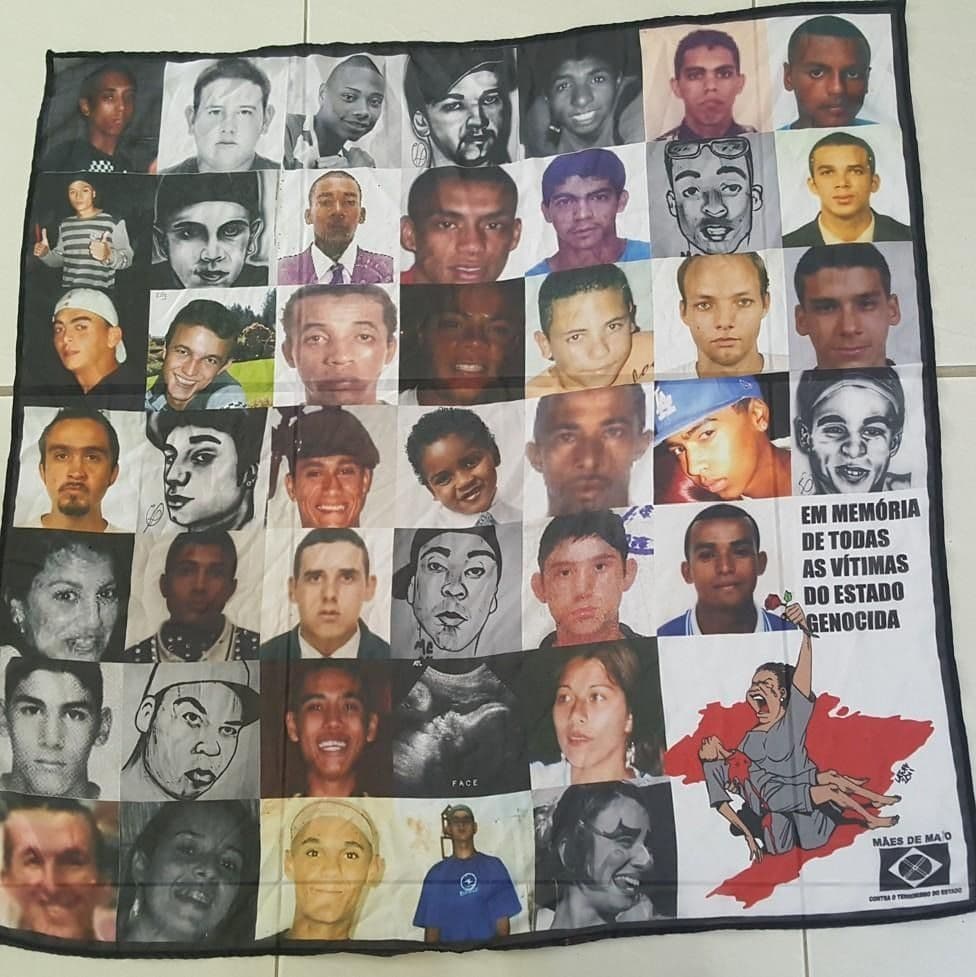

Figure 2. Mais de Maio banner for slain Brazilian youth and children of maternal activists killed by police, paramilitary, gangs, displayed on the floor of the 2018 trinational Brazil-Colombia-US meeting, mothers’ opening ceremony. Cali, Colombia, September 7, 2018. Photo by Joy James.

One of the maroon sites in which this work has emerged is that of organic intellectuals and healers among politicized captive maternals. A prime example of activism from captive maternals, in dialogue with international women, would be the contributions made by Chicago citizen-activists Dorothy Holmes and Shapearl Wells, who lost their sons to violence—Ronald “Ronnieman” Johnson on October 12, 2014 and Courtney Copeland on March 4, 2016, respectively. Both mothers are in litigation with the city of Chicago and the Chicago Police Department. As attendees of the third international gathering of mothers from Brazil, Colombia, and the United States, September 6–10, 2018, in Cali, Colombia, for women who lost children to police, paramilitary, or gang violence, Wells and Holmes shared counseling and advocacy with their Brazilian and Colombian peers (Figures 1 and 2). Both Chicago mothers expressed awareness that their grief could be used in performative ways to showcase media and academic platforms that failed to acknowledge astute forms of maternal politics emanating from traumatized households. Holmes and Wells have created nonprofits serving local communities in their sons’ names and continue to work to hold government accountable for police violence and social neglect.50 They did not write the rules for political games in which state “security” functions as predatory and indifferent policing. Yet they have dedicated their lives and the memories of their slain children to creating sanctuaries that will safeguard the lives of our community and kin.

Acknowledgment

This article is dedicated to the ancestral and revolutionary abolitionist black mothers Marielle Franco (1979–2018) and Erica Garner (1990–2017).

1. Quotation taken from documentary video 2018 pilot by Rita Moreira Videos, “Caminhada Lesbica por Marielle,” August 9, 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0OTHoAT4TEw (accessed September 10, 2018).

2. See Joy James, “The Womb of Western Theory,” Carceral Notebooks 12, no. 1 (2016): 253–96.

3. Shaun King, “The Assassination of Human Rights Activist Marielle Franco Was a Huge Loss for Brazil—and the World,” The Intercept, March 16, 2018.

4. The October 2018 election of Brazil President-elect Jair Bolsonaro—known as the “Trump of the Tropics”—singles the rise of another authoritarian figure hostile to liberal democracy and avidly opposed to the rights of blacks, women, LGBTQ communities and intent on establishing “law and order” through restrictions or abolishment of abortion, affirmative action and civil rights, and secularism. See Nathan Gardels, “Brazil: The Latest Domino to Fall,” The Washington Post, November 2, 2018 (accessed November 5, 2018).

5. Dan Baum, “Legalize It All: How To Win the War on Drugs,” Harper’s Magazine, April 2016.

6. Correio Braziliense, “Obama fala sobre a crise politica no Brasil,” March 3, 2016, http:// www.correiobraziliense.com.br/app/noticia/mundo/2016/03/23/interna_mundo,523831/ obama-fala-sobre-a-crise-politica-do-brasil-durante-visita-a-argentina.shtml (accessed November 10, 2016).

7. White House, “The White House Press Release,” September 22, 2016, https://www. whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2016/09/22/readout-vice-president-bidens-meeting-president michel-temer-brazil (accessed November 10, 2016).

8. Tathagatan Ravindran and Charles R. Hale, “Rethinking the Left in the Wake of the Global ‘Trumpian’ Backlash,” Development and Change 48, no. 4 (2017): 834–44.

9. Charles R. Hale, Pamela Calla, and Leith Mullings, “Race Matters in Dangerous Times: A Network of Scholar-Activists Assesses Changing Racial Formations across the Americas— And Mobilizes against Renewed Racist Backlash,” NACLA Report on the Americas 49, no. 1 (2017): 86. Scholars argue that the current “shift” in hemispheric racial projects reflect an adjustment in post–World War II racial governance. See Howard Winant, The World Is a Ghetto: Race and Democracy Since World War II (New York: Basic Books, 2001), 83.

10. Jo~ao Costa Vargas, “Black Dis-identification: The 2013 protests, Rolezinhos, and Racial Antagonism in Post-Lula Brazil,” Critical Sociology 42, no. 5 (2013): 551–65.

11. Joy James, The New Abolitionists: (Neo) Slave Narratives and Contemporary Prison Writings (Albany: SUNY Press, 2005); Saidiya Hartman, Scenes of Subjection (New York: Oxford UP, 1997); Angela Davis, Are Prisons Obsolete? (New York: Seven Stories Press, 2001).

12. Rachel Glickhouse, “Roundup: U.S.-Brazil Deals Forged during Rousseff’s Washington Visit,” July 1, 2015, http://www.as-coa.org/articles/roundup-us-brazil-deals-forged-during rousseffs-washington-visit (accessed November 10, 2016).

13. American Air Force Press Release, “Palleta Visits Brazil’s War Superior College,” April 25, 2012, http://www.defense.gov/news/newsarticle.aspx?id¼116089 (accessed January 10, 2014).

14. Alvite Ningthouja, “FIFA World Cup 2014: A Gateway to Israel-Brazil Defence Ties,” March 12, 2014, http://isssp.in/tag/israel-brazil-military-cooperation/ (accessed November 12, 2014); Marina Pomela, Defense Sector in Brazil, http://thebrazilbusiness.com/article/ defense-sector-in-brazil (accessed November 15, 2016).

15. Patricia Mello, “Paramilitares americanos treinam policia brasileira para a copa,” Folha de S. Paulo, April 10, 2014, http://www1.folha.uol.com.br/cotidiano/2014/04/1443261 paramilitares-americanos-treinam-policiais-brasileiros-para-a-copa.shtml (accessed May 12, 2014).

16. Moon-Kie Jung, “Constituting the US Empire-State and White Supremacy: The Early Years,” in State of White Supremacy: Racism, Governance, and the United States, edited by Moon-Kie Jung, Joao Costa Vargas, and Eduardo Bonilla-Silva (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2011), 1–26; Faye Harrison, “Global Apartheid, Foreign Policy, and Human Rights.” Souls 4, no. 3 (2002): 46–68; Joy James, “Introduction,” in Warfare in the American Homeland: Policing and Prison in a Penal Democracy, edited by Joy James (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007); Christen A. Smith, “Strange Fruit: Brazil, Necropolitics, and the Transnational Resonance of Torture and Death,” Souls 15, no. 3 (2013): 177–98.

17. Smith, “Strange Fruit”; Lesley Gill, The School of the Americas: Military Training and Political Violence in the Americas (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2004).

18. Lesley Gill, The School of the Americas. See also School of Americas Watch, “The Impact of the SOA on Colombia,” January 8, 2013, http://www.soaw.org/about-the-soawhinsec/ colombia/3470-the-impact-of-the-soa-in-colombia (access April 10, 2016).

19. Forum Brasileiro de Seguranc¸a Publica, Anuario Brasileiro de Seguranc¸a Publica (Sao Paulo, 2017); Human Rights Watch, Lethal Force: Police Violence and Public Security in Rio de Janeiro and S~ao Paulo (Executive Summary, Washington, DC, 2009).

20. Bob Barry and Jones Coulter, “Hundreds of Police Killings Are Uncounted in Federal States,” The Wall Street Journal, December 3, 2014, http://www.wsj.com/articles/hundreds of-police-killings-are-uncounted-in-federal-statistics-1417577504 (accessed May 10, 2015).

21. Jamiles Lartey, “The Uncounted,” The Guardian, June 9, 2015, https://www.theguardian. com/us-news/2015/jun/09/the-counted-police-killings-us-vs-other-countries (accessed December 10, 2016).

22. International Amnesty, Bringing Human Rights Home: Chicago and Illinois, Torture and other Ill-Treatment (Executive Report, Washington, DC, 2014).

23. The Guardian, “The Disappeared,” February 2, 2014, http://www.theguardian.com/us-news/ 2015/feb/24/chicago-police-detain-americans-black-site (accessed January 10, 2015).

24. Otwin Marenin, “Police Training for democracy,” Police Practice and Research 5, no. 2 (2004): 107–23; Paul Chevigny, Edge of the Knife: Police Violence in the Americas (New York: New Press, 1995); Robert J. Kane and Michael D. White, Jammed Up: Bad Cops, Police Misconduct, and the New York City Police Department (New York: NYU Press, 2012).

25. Steven Martinot and Jared Sexton, “The Avant-Garde of White Supremacy,” Social Identities 9, no. 2(2003), 169–81; Jaime Amparo Alves. The Anti-Black City: Police Terror and the Struggle for Black Urban Life in Brazil (Minneapolis: Minnesota University Press, 2018).

26. See governor’s speech at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v¼Im2YKABgMNo (accessed February 12, 2016).

27. Raquel Luciana de Souza, “Ethnographic Notes from a War Zone: Surviving and Resisting,” LASA Forum 17, no. 2 (2017): 34–36.

28. Correio da Bahia, “Chacina com 12 mortos no Cabula foi planejada por PMs como vinganc¸a,” May 18, 2015, https://www.correio24horas.com.br/noticia/nid/chacina-com-12 mortos-no-cabula-foi-planejada-por-pms-como-vinganca/ (accessed July 2, 2015).

29. Correio da Bahia, “Familiares de mortos no Cabula fazem novo protesto contra ac¸~ao da PM,” February 11, 2015, http://www.correio24horas.com.br/detalhe/noticia/familiares-de mortos-no-cabula-fazem-novo-protesto-contra-acao-da-pm/?cHash¼f5356da0bfafdaaa65636 6bd5e53931e (accessed September 16, 2015).

30. Phillip Bump, “How Ferguson Happened,” August 18, 2014, http://www.washingtonpost. com/blogs/the-fix/wp/2014/08/18/how-ferguson-happened/ (accessed October 10, 2014).

31. Department of Justice, “Investigation of the Ferguson Police Department,” March 14, 2015, http://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/opa/press-releases/attachments/2015/03/04/ferguson_ police_department_report.pdf (accessed April 14, 2015).

32. Ibid.

33. See Judith Butler, “Endangered/Endangering: Schematic Racism and White Paranoia,” in Reading Rodney King/Reading Urban Uprising, edited by Robert Gooding-Williams (New York: Rutledge, 1993), 15.

34. For the “pacification” program and its racialized outcomes, see Jo~ao H Costa Vargas, “Taking Back the Land: Police Operations and Sport Megaevents in Rio de Janeiro,” Souls 15, no. 4 (2013): 275–303.

35. Aluisio Freire, “Cabral Defende Aborto Contra Viol^encia no Rio,” Portal G1 Online, April 15, 2014; for a discussion on the criminalization of black women’s reproductive rights in the United States see Dorothy Roberts, Killing the Black Body: Race, Reproduction, and the Meaning of Liberty (New York: Vintage Books, 1999).

36. Faye Harrison, “Global Apartheid, Foreign Policy, and Human Rights,” Souls 4, no. 3 (2002): 46–68. For the place of black women within the racial regimes of U.S. and Brazilian security, see, respectively, Hazel Carby, “Policing the Black Woman’s Body in an Urban Context,” Critical Inquiry 18, no. 4 (1992): 738–55 and Luciane de Oliveira Rocha, “Black Mothers’ Experiences of Violence in Rio de Janeiro,” Cultural Dynamics 24, no. 2 (2012): 59–73.

37. This sexualized/raced/gendered dynamics of security manifests in global south cities’ use as militarized sites. Soldiers and contractors from the U.S. wars in Iraq and Afghanistan self-medicate post-traumatic disorder through sex tourism in Brazil and Latin America. See Sara Miller Llana, “El escandalo del Servicio Secreto arroja luz sobre el turismo sexual en America Latina,” The Christian Science Monitor, April 12, 2012, https://www.csmonitor. com/World/Americas/2012/0417/Secret-Service-scandal-sheds-light-on-sex-tourism-in-Latin-America (accessed May 10, 2015).

38. Kimberle Crenshaw and Andrea Ritchie, #Say Her Name: Resisting Police Brutality Against Black Women, African American Policy Forum, February 5, 2015, http://www.aapf.org/ sayhernamereport/ (accessed May 10, 2015).

39. Kelly Hayes, “Protesters Demand Justice for Sandra Bland,” Truth-Out, July 29, 2015, http://www.truth-out.org/news/item/32130-say-her-name-protesters-in-chicago-demand-justice for-sandra-bland (accessed Dec 10, 2016).

40. InterAmerican Commission of Human Rights, “CIDH apresenta caso sobre o Brasil a Corte IDH,” May 7, 2015, http://www.oas.org/pt/cidh/prensa/notas/2015/069.asp (accessed June 12, 2015).

41. Crenshaw and Ritchie, #Say Her Name.

42. Ibid. U.S. black women account for approximately 20% of the unarmed victims of police killings; percentages of police shootings/killings of blacks is 94% male to 6% female. In New York City, black and Latina women accounted for 80.9% of all women stopped by the New York Police Department in a given year.

43. Sergio Carrara and Adriana Vianna, “‘Tala o corpo estendido no ch~ao …’: A viol^encia letal contra travestis no municpio do Rio de Janeiro,” Physis: Revista de Saude Coletiva 16 (2006): 233–49.

44. Debora Silva, City University of New York-Staten Island, May 2016.

45. Joy James, “The Womb of Western Theory,” Carceral Notebooks 12, no. 1 (2016): 253–96.

46. Thandara Santos, “Somos Todas Claudia,” Blog da Marcha Mundial das Mulheres, https:// marchamulheres.wordpress.com/2014/03/18/somos-todas-claudia/ (accessed November 19, 2015).

47. Rita Moreira Videos, “Caminhada Lesbica por Marielle.”

48. Aretha Franklin, “Mary, Don’t You Weep,” January 13–14, 1972, with James Cleveland and the Southern California Community Choir.

49. Joy James, The New Abolitionists, xvii.

50. See Charles Preston, “Mother on a Mission Caption: Dorothy Holmes Celebrates the Life of Her Slain Son through Activism,” Chicago Defender, May 10, 2018, https:// chicagodefender.com/2018/05/10/mother-on-a-mission-caption-dorothy-holmes-celebrates-the life-of-her-slain-son-through-activism-and-community-engagement-mother-on-a-mission-by charles-preston-defender-contributing-writer-ever/ (accessed September 30, 2018); and Brittany Reyes, “Devastated Mother Looks for Answers, Has ‘Zero Percent Confidence’ in CPD Finding Killer of Courtney Copeland,” Homicide Watch Chicago, April 18, 2016, http://chicago.homicidewatch.org/2016/04/18/devastated-mother-looks-for-answers-has-zero percent-confidence-in-cpd-finding-killer-of-courtney-copeland/ (accessed September 30, 2018).