Sonicate

biochemistry

verb. subject (a biological sample) to ultrasonic vibration so as to fragment the cells, macromolecules, and membranes.

noun. a biological sample which has been sonicated.

Constitutive

biochemistry

adj. relating to an enzyme or enzyme system that is continuously produced in an organism, regardless of the needs of the cell.

Jazz provided the soundtrack for Chinese modernity. It helped fuel its entertainment industry and created new public/private social spaces for the interaction of hitherto highly traditional gendered and racialized relations in Chinese urban areas. Furthermore, the arrival of African American musicians in China put into stark relief the historical reception of the Black ‘other’ as exotic, primitive, and undesirable. To be a modern subject in the Republican era (1919– 1949) China, specifically in treaty port cities such as Shanghai, meant listening and dancing to American jazz music. Shanghai residents were sonically showered daily via radio broadcasts, phonographs, and live music. Even some literature of the period often featured a dance club or jazz musician Jazz also engendered and embodied an alternative, nontraditional social space for the interaction of multiracial groups centered-around improvisational music. Mediated through African American jazz music, musicians from around the world collaborated, learned, listened and played jazz in China. Whether the music heard originated directly from Black musicians themselves or entered the Shanghai soundscape through movies, radio, or the play of white or Asian musicians, the imprint of music created by Black musicians was ever-present. Whether one enjoyed the music or not, it was impossible to escape its reverberations and proponents and detractors alike had to react, to adjust, to fight for and against the new modern soundtrack.

From the mid 1920s, African American Jazz music and musicians of the Harlem Renaissance/The New Negro Movement embodied and promulgated ideas of modernity and freedom through their music and presence in China. Itinerant and long-term Black musicians from America residing in Shanghai and other semi-colonial Chinese cityscapes during the Republican era (1919–1949) fostered an alternative racially-inclusive social community outside the U.S. based on the practice and tradition of improvisational music. Jazz music and the community built around it provided a blueprint for the potential expansion, influence and fraternity between African American, Chinese and other international cultures via the first globalized popular music of the twentieth century. This is not to discount the other world or ethnic musics that were popular at the time, European classical, folk musics, etc. in what Michael Denning called “a new musical world-system. I argue, however, that no other music, captured the zeitgeist of the modern era and impacted the popular musical landscape that gave rise to other world defining genres such as Rock and Roll, Country, Rhythm and Blues, Pop, and Hip-Hop to name a few. In addition, Black musicians and dancers were directly responsible for creating the music and the dance choreography for the Fox-Trot—one of the most influential dances of the early twentieth century—that took the world, including Shanghai, by storm

Both the incumbent Chinese Nationalist Party’s and the nascent Chinese Communist Party’s interpolation of jazz’s social and political utilization was devalued and would highlight centuries of anti-Blackness already extant within Chinese culture. While living outside the rigid confines of the American color-line, but nonetheless not immune to its global reach, African American jazz musicians in Shanghai, for a brief time, enjoyed financial freedoms commensurate with their skills and exemplified the best traditions of the practice of jazz—free transfer of knowledge and ideas, democratic values, and humanitarian liberalism. From Shanghai, this early praxis of globalization would spread across Asia through the medium of Black improvised music carried by Black, white and Asian musicians alike. Other locales in Asia offered a similar personal and economic freedom, but places like the Philippines, an American colony at the time, can be argued operated under the closer purview of American racial politics where restrictions on who could dance in jazz cabarets were more strict. Unlike Shanghai for instance, white female dancers were not allowed to work the dance halls in colonial Manila so as to maintain a sense of racial superiority and propriety

This paper addresses the understudied topic of Black musicians and entertainers in Shanghai during the Republican era. Despite the vast literature on Shanghai during this time, there is a dearth of scholarly work during this period focused specifically on how African American jazz musicians and their Black musical esthetic and traditions engendered and became constitutive of Chinese modernity. This paper argues that the Black cultural production of jazz musicians not only fueled the cultural industry of Jazz Age Shanghai and created alternative social spaces for the practice of a global internationalism, but also revealed the racialization of Chinese anti-blackness that differs from the Western version, ironically, during the early formation of Sino-Black solidarity with the left-wing in China in the 1930s. This study examines advertisements, trade magazine articles, memoirs and most importantly, period-specific movies and popular songs to frame a narrative of the impact of a small, but influential group of African American musicians on the culture of modernity and the potentiality of Afro-Asian solidarity in China in the first half of the twentieth century and beyond. This paper privileges the use of race as a critical lens of analysis to the formation of the modern in early twentieth-century Shanghai.

The lives of African American musicians and the music they played in Shanghai illuminates the intersecting themes on race, class, music, and spatiality that have been put forth and touched on to various degrees by scholars My contribution to these works will be to focus the lens of race on Jazz Age Shanghai. In this instance, the lives of the African American sojourners are instructive in giving clues about the nature of the life Black musicians led in the ‘Paris of the East’ and give a visceral sense of how the Chinese approached and understood Blackness there and how this music and its musicians became constitutive of and provided the soundtrack for Chinese modernity. Black Americans in China during this time were essential to what Leo Ou-Fan Lee described as “… new forms of cultural activity and expression made possible by the appearance of new public structures and spaces for urban cultural production and consumption. It was within these new spaces that Black men and women played the music that accelerated the modern mode of social and cultural interaction in cabarets and taxi clubs that fueled the famed Shanghai night life. It is also what Mbembe refers to more explicitly in terms that “The noun “Black” is in this way given to the product of a process that transforms people of African origin into living ore from which metal is extracted. This is its double dimension, at once metaphorical and economic. The Black music of African Americans was not only embedded into the new mass media cultural technologies of film and radio, but also provided momentum for the formation of these nontraditional urban spaces and nodes of connection between genders and cultures in Shanghainese night clubs. Cabaret culture and dance halls were predicated on the interaction between male clients and female hostess who gyrated to sonicated Blackness with dances like the Charleston and Jitterbug (Lindy Hop). Many within the international community of non-black musicians in Shanghai also benefited from the social and cultural contacts with Black musicians playing the latest musical innovations from places such as Chicago and Harlem. Black music had so thoroughly encircled and integrated into the Chinese cultural milieu that it drew the attention of and received critical response from both the Guomindang Nationalist government and the burgeoning Chinese Communist Party. The negative reaction was definitive and swift. For the Chinese Nationalists, jazz was created by a racially inferior people and did not mesh with the vision of their society. Similarly, for the Chinese Communists jazz evoked the sentiments of a decadent and bourgeois community it sought to eradicate. The Guomindang government unsuccessfully attempted to ban the cabarets and discredit Black music since the 1930s. It would take the Communist Party four years after the country’s liberation in 1949 to completely stamp out the official public consumption of jazz

The rise and popularity of jazz in China appeared in the wake of the New Culture Movement (1910s–1920s) with its emphasis on ideas of individuality, the promotion of literature based on a common Chinese vernacular, women’s liberation and the rejection of Confucian values of fixed hierarchical obedience and conformity. A similar explosion of culture and intellectual curiosity was thriving simultaneously across the ocean in Black Harlem and other African American loci around the U.S. including the West Coast That this Black cultural production touched and resonated on the opposite side of the Pacific Ocean via technology and transpacific ocean voyages speaks to its cultural ubiquity and visibility. Jazz music, essential to Shanghai’s modernity ethos, also experienced the beginning of the Nationalist government’s New Life Movement (1934–1936) that sought to reintroduce and inculcate conservative Confucian values to Chinese society. This African American art form not only became the symbolic antithesis of the Chinese Nationalists government’s policy to eradicate jazz and dance culture nightclubs in Shanghai by the mid-1940s, but also became the target of Nationalist writers, and those on the Chinese Left that promoted expressions of Blackness as primitive and backwards. Jazz music critique in Shanghai in the early twentieth-century, not unlike its Western discursive counterparts of the time, also found popular expressions of otherization in its magazines, journals and periodicals that either erased, denigrated or misconstrued the music and its Black roots while also simultaneously acknowledging its uniqueness and impact on Chinese society. The sociocultural function and nature, however, of the music and the musicians who played it became lost in the deployment of a Chinese discourse of Black otherness that not only acted as a fulcrum to secure their own racial position and status confronted with Western imperialism and fixed ideas of modernity, but also demonstrated their own sentiments toward Blackness. The origins of Black racialization predate the arrival of Western ideology on Blackness. The Chinese intelligentsia in the early twentieth century promoted long-standing notions of color and otherizing that were reified and concretized both knowingly and unwittingly in Chinese cultural production that conformed not only to Western racial paradigms of people with darker hues, but also to the historical continuities of the “other” by the Chinese toward Blackness expressed in conceptions of Chineseness and “civilization” from as early as the 5th century CE to the 20th century discourse on race in Chinese modernity entangled with the creation of a new Chinese modern nation/state Unlike, Western discourses on race, there are no Chinese treatise per se that attempt to outline any historical genealogy on ideas of race or system of racial categorization based on scientific, biological, or religious rationale. There are, however, fragments and anecdotes from official recorded histories and fictional texts that taken collectively reveal a consistent trajectory of the otherization of Black bodies that places it outside the putative Sino-Confucian universalism This also refutes the notion that Chinese 20th century racism was a sole product of modes of anxiety stemming from exposure to Western modernity, but in fact has its own historical lineage traced in China’s own contact with the Black other Harold Isaac, the American journalist and political scientist, wrote in 1967 that the Chinese attitudes toward skin color had been cemented long before the arrival of Europeans Chinese intellectuals, of course, expressed their own agency and not all subscribed to essentialist notions of Blackness. For example, Lu Xun, the father of Modern Chinese Literature, publicly rebuffed assertions to the contrary that African American fiction had no merit. In response to the Chinese modernist poet Shao Xunmei’s disparaging remarks about Black literature as derivative and not useful outside the American context, Lu Xun replied, “my voice has come out. And Black poetry has also gone beyond the Anglophile confines. Lu Xun would have been familiar with works by African American writers through his mentorship of Zhao Jiabi, the owner and editor of Liangyou Publishing Press which edited and published several works of African American writers, including a compendium of Black writers in his publication. Zhao Jiabi corresponded with Lu Xun until his death in 1936. Chinese intellectuals were engaging with Black cultural production. Unfortunately, the anti-Black Chinese sentiment of some of these intellectuals played a crucial role in further cementing negative racial notions of the Black other. And in doing so, many failed to understand African Americans and jazz on its own terms, especially, in the socio-cultural sphere of engendering an alternative social community based on mutual respect for jazz in a non-racialized space devoted to collaboration and learning Lastly, given Shanghai’s unique position as a multicultural and administrative semi-colonial polity, it became the space for one of the first formations of mass global Black cultural appropriation in the 20th century. The translation, modification, and deletion of the jazz idiom into different cultural milieus, particularly Chinese ones by African American and eventually Chinese musicians is an insightful journey into the music’s dissemination and evolution. How do we measure jazz’s distinct relationship with China vis-'a-vis other colonial locales and metropoles? How has the localization of Black music impacted the idiom, if at all? By privileging the Chinese experience with jazz in the interwar years, mediated through race, we can further complicate and problematize what one scholar argues, is the jazz in “Chinese jazz” and the “Chineseness” of jazz that facilitated its translation and legibility Most importantly still is to center Blackness as represented by jazz, in this particular instance, as the locus of China’s modernity and to resonate it through the various valences that underpin its significance. In this way, it is possible to discover in the interstices neglected historical realities.

Shanghai, unlike Paris and Harlem, was a multinational colonial space that was divided into distinct geographical and cultural zones—the international settlement and the French concession that was administered by a multinational municipal council made up mainly of American, British, and Japanese provided a unique environment for jazz to thrive While there were elite Chinese who lived within the concessions, most of the three million middle and working class Chinese lived outside of the foreign concessions. Members of the middle-class worked as bank tellers, shop assistants, etc. The working-class Chinese migrated into the city from rural areas and worked in the many factories in and around the city or became destitute and beggars or found their way into the sex industry which was constitutive of the allure of the famed Shanghai night life The other part being its vast number of cabarets and nightclubs that catered to the wealthy foreign and Chinese elite as well as 2nd and 3rd tier venues for the burgeoning middle class Chinese worker. Shanghai attracted an international cornucopia of expatriates and refugees from different locales partly due to its lack of visa requirement at the Shanghai port of entry. Russians who fled the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, Japanese, and Filipinos alike found a new space to reinvent themselves in China. On Shanghai streets in the international concessions one could hear a myriad of languages and meet a number of different people from various cultures interacting with each other. Shanghai, by the 1930s was controlled by a multinational and multicultural oligarchy of imperialists, business figures and missionary elites along with a new class of Chinese bourgeoisie and entrepreneurs, some of whom made their money during the World War I economy, who owned and ran banks, factories, and nightclubs The cabarets and nightclubs employed thousands of workers by the 1930s where the various Black musicians and performers plied their trade.

Shanghai, for African American jazz musicians in the interwar years (1919–1937), provided an unprecedented level of economic and social freedom that they would find difficult to match in the U.S. This massive semi-colonial city, however, still bore and could inflict dynamic wounds from race, gender, and class conflict by the elite colonial powers as well as the local Chinese host. The mutual lack of familiarity among African Americans and Chinese with respect to cultures and languages would further limit cross cultural understanding and centuries of indigenous anti-blackness in some quarters of China would find new expression in the reception of the music most commonly known as jazz In many Chinese circles, these Black musicians, while recognized as singular talents, were not held in such high regard as the African American musicians in France at the end of World War I who were a part of a liberating army fighting for and with French allies and who were also treated with humanity and respect. Many French generals and people derided the segregationist policies of the U.S. military that sought to keep Blacks and whites separated. Some French citizens actually preferred to socialize with Black American troops over white ones. Perhaps the presence of a number of African American marching bands who played across France, particularly composer and conductor James Reese Europe’s all-Black regiment band performed to great fanfare throughout France to thousands of French people. Along the way, they generated much goodwill and adulation for their unique sounding performances One mayor of a French village complained when he discovered the occupying soldiers coming to his town were white Americans, he exhorted, “Take back these soldiers and send some real Americans, Black Americans. This French experience with Blackness that combined a welcomed allied foreign military presence and music did not exist in the same fashion in multinational Shanghai where the military was viewed as a humiliating occupying force. In addition, Shanghai was still in many ways a fragmented and segregated space. In fact, during World War II, nationalist leader Chiang Kai-Shek, attempted to limit the contact between Black and Chinese soldiers in the Burma Theater as U.S. forces built and established the Burma/Stilwell Road supply line into China’s Southwestern Yunnan Province This is not to say, however, that the French did not behave with condescension and racial bias toward African Americans and certainly against other people of color from their colonial regimes outside the metropole In the Philippines, the reception of African Americans was more directly tethered to the American empire. Black soldiers manned the armies of the colonial power which not surprisingly engendered a sympathy and solidarity to Filipino revolutionaries, leading some Black troops to defect, the most famous case was that of David Fagan, a Black soldier who accepted an officer position within the revolutionary army and led Filipino troops against U.S. forces. Some 1200 Black GIs stayed on in the Philippines after that country’s war of independence In addition to the sentiment of martial solidarity with the Filipino cause, Black musicians were admired by Filipinos who themselves enjoyed a rich heritage of musical excellence. This was epitomized in the relationship between Walter H. Loving, the African-American founder and bandleader of the Philippine Constabulary Band and the Filipino musicians under his leadership Despite the camaraderie between working-class Filipinos and former Black military men, the Filipino elite (whose identity was tied into Spanish, Chinese, and indigenous ethnicity) did not share the same reverence.

Similar to Paris and to a certain extent Manila, Shanghai perhaps featured more prominently in the African American jazz musicians’ utopian imagination. In 1924, The band leader Fletcher Henderson, recorded the song “Shanghai Shuffle.” This uptempo tune captured the feeling of the frenetic pace of the so called “Paris of the East.” As one writer wrote, the “Shanghai Shuffle” is an attempt to "reinforce the exotic jazz-Chinese connection. More than that, it spoke to the cognizant awareness of the opportunity the city represented for Black musicians as the progenitors and inheritors of the music that Shanghai could not do without. The shuffle could perhaps also be a reference to a hustle that paid huge dividends. African American jazz musicians could make 4-5 times more than their Japanese counterparts (who were at lowest end of the pay scale) who mostly played in the Hongkou section of Shanghai.

Black musicians also assisted their white counterparts. For instance, Fletcher Henderson exchanged musical sheet arrangements with Paul Whiteman, the film industry’s appointed “King of Jazz” due to his 1930 Universal Studio film of the same name which was screened in Shanghai in November 1930, just under seven months after its American debut. Whiteman, to his credit, worked to hire Black musicians and composers when possible. African American composers such as Eubie Blake, co-composer of the Broadway musical Shuffle Along (1921) and William Grant Still, composer of Afro-American Symphony (1931) the composition that catapulted him to worldwide fame, were key to the success of white band leaders. William Grant Still was responsible for many of Whiteman’s popular works and lauded as the first American composer to integrate the blues and jazz into his compositions These and other Black musicians and composers were integral to the success of their white counterparts at a time of de jure segregation in America that precluded the public interaction of Black and white musicians.

In other parts of Asia, such as the Philippines, the racial dynamics of African American musicians differed significantly. There seemed to be much more interaction with local people and a greater potential for solidarity with local communities, of course, dependent on class considerations in addition to racial ones

In addition to phonograph records that were playing songs like the “Shanghai Shuffle”, African American composers were contributing to the works of the most famous bands of the time, Black musicians in the mid to late 1920s began playing on the ocean-liners traveling across the Pacific on its three to four-week journey to Asia. Shanghai became a major locus for the fortunate jazz musician who got the opportunity to get a gig there. Jazz broke on to the scene early in the 1920s. White band leader, Whitey Smith is widely credited with bringing jazz to China and teaching the Chinese how to dance–he famously played for Chiang Kaishek’s, Nationalist Party’s military and political leader, wedding in 1927. It was African American musicians, however, that catapulted, what was called the ‘dance craze’, ‘dance heat’ and ‘dance madness’ into the Chinese stratosphere New modern mass media technologies played a huge role in disseminating music and culture. Phonograph records had been around since the 1910s. Talking movies appeared in the US on October 6, 1927. And almost just as soon appeared in Shanghai. These movies are important not only because the masses of Chinese who could afford to do so were consuming them, but also because Chinese musicians were canvasing the theaters transcribing and scoring all the latest music they heard. This transcription of aural Black jazz to Chinese text and back again into sonic form by those Chinese musicians is crucially important in that it demarcates not only the similarities and disparities in musical elements and executions but also references the social and cultural seams and fissures that announce the (in)visibility of Blackness. In other words, the spaces in which Black and Chinese musicians performed, congregated, and the music played marks their proficiency and interpellation of Black music offers insights into the realities of the relations between the two cultural groups. Were Black musicians in China interacting with their Chinese counterparts in meaningful ways professionally and personally? Did African American musicians like Buck Clayton have significant contact with Li Jinhui, one the leading composer of the jazz/Chinese folk music hybrid called “Yellow Music”? Unfortunately, many of the recordings from the period were lost during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) due to mishandling, improper storage, and destruction of the very fragile and brittle shellac-records. We are left with a limited number of examples of this music from movies from famous Chinese stars such as Zhou Xuan that are indicative of how Chinese musicians were digesting Black music. Moreover, Chinese audiences were also viewing the many stereotypical and racialized imagery such as Blackface performances and exotic histrionics that were required of Black musicians when engaged in jazz performativity that had to satiate and meet the demands and expectations of both white and Chinese consumers of Black cultural production of the putative “authentic” Black other. Important to note that this racial otherizing did not originate with this new media, but served to further reinforce existing ideas about Blackness as primitive, backwards, lascivious, unintelligent, comedic and unattractive that existed in China for over a millennium

Consequently, the Shanghai film industry was key in screening several films from early 20th century American productions that promoted and enforced racialized stereotypes of blackness that conformed and resonated with Chinese ones. Al Jolson’s Hollywood movie The Jazz Singer appears in Shanghai on April 25, 1929, a little over a year and a half after its U.S. debut. Marketed as a story of filial piety between father and son, Jolson’s character Jack is torn between the secular world of a jazz singer and his traditional Jewish heritage. After his hard earned success to be a top singer is realized, Jack must choose between his career and his responsibility to stand in for his father, who is on his death bed, in a community ceremony that requires his vocal talents. Jack decides to perform a final act of filial piety for the sake of reconciliation with his father and manages to retain his headliner position at the theater. The denouement of Jolson’s character reaching stardom and performing in blackface on a high profile stage for a mass audience with his mother in attendance adds the coda to the movie. The Jazz Singer was screened in numerous theaters in Shanghai. Billed as a movie celebrating the hardships and redemption of a filial son. Chinese audiences are regaled by an artist who during his breakthrough concert for a large venue dons Blackface to the accolades of those in attendance. The wearing of Blackness signifies, instills and solidifies in the consumer the notion that Black equals a certain kind of musical affect inherent within its character. This was not the first time that a Chinese group experienced a blackface production. Chinese students studying abroad in Japan in 1907 performed adaptation of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin on stage. Chen Xiaomei and Claire Concesion both argue for an indigenous Chinese construction of racial representation that operates independent of Western discourses of race to fit their own realities It would be wrong to assume that only the wealthy, English-speaking Chinese elite were fervid in their consumption of blackness. In the Shenbao, one of China’s most popular Chinese-language daily newspapers with a circulation of around 150,000 subscribers by the mid-1930s, ran many advertisements of jazz performances, jazz-inspired biopics, and dances that peppered the entertainment section. Between 1929 and 1943 there were around 78 advertisements taken out in this daily periodical promoting mainly jazz related movies, but also performances by African American artists. The cost of attendance was well within the budget of a working class Chinese person. Depending on the time of day and the show time, a ticket could cost as little as 20 cents to upwards of 1 yuan for special performances.

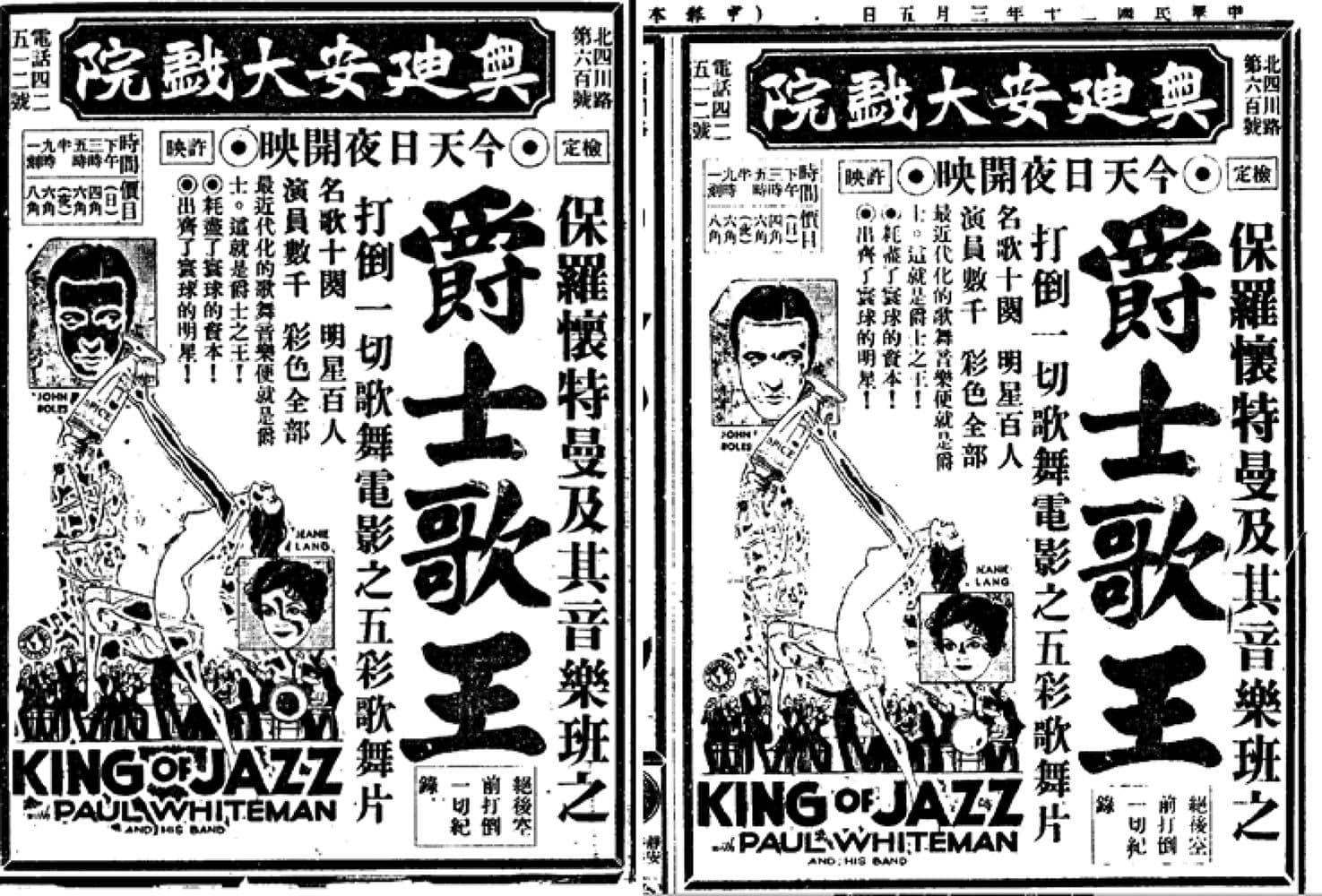

In addition to the ubiquity of Al Jolson’s The Jazz Singer and The Paul Whitman biopic King of Jazz, (Jueshi Ge Wang) was another popular American movie screened in Shanghai around the same time as The Jazz Singer. Between 1930 and 1933 advertisements for the King of Jazz appear in the Shen Bao entertainment section no less that sixty-one times. On March 5 and 6, 1931 the advert for Shanghai’s Odeon (see Figure 1) runs the same add on consecutive days—a common practice. The ad declares, “Paul Whitman and his band’s movie—King of Jazz has beat every record and every other musical and dance movie … Jazz music is the most modern song and dance music.” The visual image on the ad features what appears to be a side profile of a naked woman who with outstretched arms and her head tilted back pours a substance out of a glass. The glass has the word

Figure 1. “King of Jazz”, Shenbao Chinese newspaper, Movie Advertisement.

‘spice’ printed on it. The contents pouring from the glass seem to be musical notes and abstract naked human figures. At the bottom of the print is a full-band playing with energy and alacrity as connoted from the upright positions of the hands, arms and instruments of the figures frozen in mid-motion. The upper left-hand corner of the image features the face of the star male actor—John Boles. On the March 5th advertisement John Boles face is printed with black ink as to mimic Blackface and the next day the Boles’ face is white, clear of the black print from the day before. This appears to be a cognizant nod to the only Blackface performance in the entire movie. During one scene a white dancer donning Blackface erupts into what is supposed to be a stylized African dance. Ironically, the erasure of any other link to jazz and African American culture is absent from this film, so it is peculiar that Shenbao editors and/or theater managers took out this ad in the paper would make blackface a focus of their strategy to attract audiences. Was drawing a correlation between blackface minstrelsy synonymous with Blackness and jazz music in the international concessions? Was it something that was a proven box office draw—a pull factor to entice potential Chinese consumers? At the least, this points to a basic understanding and deployment of otherizing methods on the part of Chinese media. Another American movie shown in Shanghai featuring blackface was Amos and Andy’s 1930 film Check and Double Check (see Figure 2).

Originally aired on radio as a 15-minute comedy sketch performed by white actors Freeman Gosden and Charles Correll, the radio comedy sketches follow the

Figure 2. July 16, 1931 “Check and Double Check”, Shenbao Chinese newspaper, Movie Advertisement.

lives of two fictional Black characters Amos and Andy who are portrayed as stereotypical archetypal figures that emphasize negative tropes of Blackness ranging from avarice and indolence to ignoramus and consternation. For the film version, Gosden and Correll reprise their roles of Amos and Andy in blackface. Chinese audiences like their American counterparts were inundated with various inauthentic images of Blackness through proxy that both mirrored Western notions, but also conformed to long-standing Chinese notions of Blackness and introducing new ones. In addition to the cast of white performers in blackface, about third way through the film, Duke Ellington and his Cotton Club Band give a musical performance. The scene is set in a ballroom with an all-white audience. The white figures dressed in their formal wear stop dancing and talking almost simultaneously on cue to watch Ellington’s band perform. Once Ellington leads his musicians into song and what will become his signature sound of various wails and moans produced by the brass and wind instruments; his brass players use various devices to manipulate and create the modern and unique sounds his groups would become known for. The white audience is captivated as it consumes this black cultural production in a privileged space that allows for black people to entertain in a performance of “authenticated” Blackness, but remain always a separate and disparate part of the white space that serves to solidify and define its boundaries vis-'a-vis the Black body This scene would actually be replicated in Shanghai in the 1930s many times over by the white colonial and Chinese elite in extravagant venues such as the Canidrome. In fact, Shanghai’s spatial distribution of jazz venues outpaced its Harlem counterpart. Harlem’s night clubs operated within a fixed space of no more than a 4 mile radius from the south at 124th street up north to about 149th and east from 8th avenue to the borders of the Harlem River. Venues like Small’s Paradise and the Cotton Club were all mere blocks apart. In addition, in Shanghai the monied elite and underworld gangsters invested millions in the elite ballrooms. Each trying to one-up the other in a game of highstakes “keeping up with the Jones’s” or in this case the Zhang’s (a very common

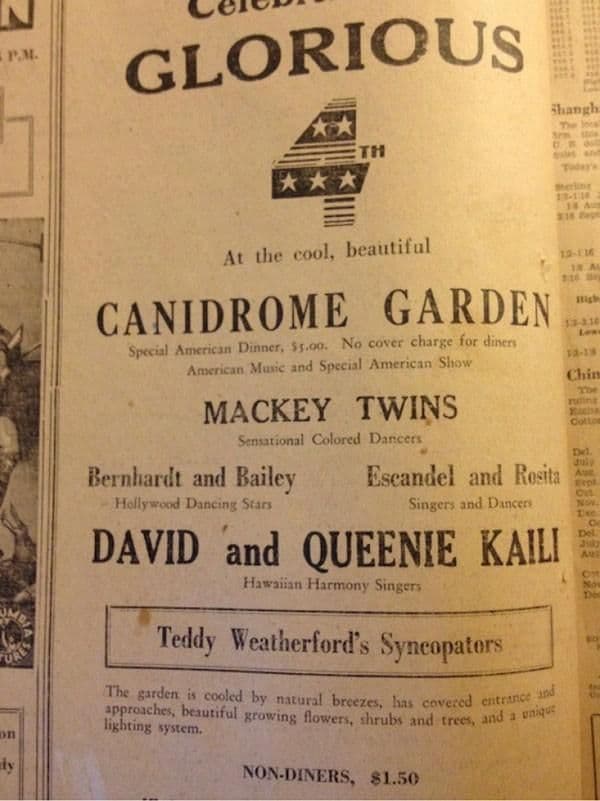

Figure 3. July 4, 1933 Shanghai Evening Post newspaper, Advertisement for the Canidrome Ballroom and Garden featuring Teddy Weatherford and his band the Syncopators.

surname in China). The most opulent ballrooms in Shanghai showcased the best materials and technology money could buy—Art Deco architecture, marble ornamentation, the best hardwood floors, and immaculate culinary experiences

Although the dispersion of dance venues within the French and International concessions as well as those in the Chinese section of town created a diluted talent pool, this bode well for the incomes of the African American Jazz musicians in Shanghai who were in high demand. During the height of the global depression Black musicians in Shanghai were making around $200 USD a month. Buck Clayton, a West Coast trumpet player who would later join Count Basie’s Orchestra described how entrepreneurial musicians like Teddy Weatherford quadrupled their income by playing at multiple venues a night earning roughly $800 USD per month. In the early 1930s, the price of a car in America hovered around $600 USD. In other Asian countries the money was just as good, if not better due to supply and demand. In the Philippines, for instance, some Black soldiers in the military band could make $500 USD a day outside of their normal working hour duties This fact, along with Clayton’s account of his spending sprees, gives some indication of the economic privilege and purchasing power the top musicians in Shanghai enjoyed. The surplus of capital, however, did not inoculate these musicians from racial sentiments that impacted their lives and would eventually change their fortunes in Shanghai. Until that time, however, they would enjoy a particular celebrity status not often afforded them in the States.

The presence of African American musicians and their Black cultural production would help fuel the Shanghai cultural entertainment industry in the 1920s and 1930s. In the July 4, 1933 edition of the Shanghai Evening Post (see Figure 3) an advertisement announced a special American Independence Day celebration at the famed Canidrome Garden, Shanghai’s premier dance club and racetrack for the Western and Chinese elites in the 1930s. Headlining the special program was David and Queenie Kaili, a duo billed as ‘Hawaiian Harmony Singers’, Berhardt and Bailey, Hollywood Dancing Stars, Escandel and Rosita, Singers and Dancers, The Mackey Twins (not actually twins or brothers), two African American tap dancers and stride pianist Teddy Weatherford and his Syncopators who performed their own pieces as well as played background for the above performers What is most fascinating about this lineup is its diversity in musical offerings for the night. This Asian vaudeville production provided seemingly disparate musical genres in one night’s program. This was not unique for Shanghai given the city’s demographic. Chinese and foreigners were of course listening to other forms of music as well as dancing to the Fox Trot, the Charleston, the Cuban Rumba, and the Tango (all musical form and dance with African American and African origins). Black jazz and Teddy Weatherford, however, by the late 1920s and early 1930s seemed to have garnered the most celebrity status, at least, among foreigners in Shanghai and English-speaking Chinese elites. A notice in the entertainment section of the March 4, 1934 North-China Daily Newspaper informed readers that:

The popular Teddy Weatherford is returning to the Canidrome Ballroom from the United States, bringing an entirely new dance band and several high-class coloured entertainers, arriving on April 10 in the Tatsuta Maru. He was sent to the United States for the express purpose of obtaining a crack dance band and outstanding artistes. The current floor show at the ballroom is regarded as the strongest presented here in years

Weatherford was so popular, Langston Hughes would recount on his visit to Shanghai in 1933, that “The Far East was his personal stomping ground. Stiffnecked Britishers and Old China hands from Bombay to the Yellow Sea swore by his music. It was the best! … Teddy could walk into almost any public space in the Orient and folk would break into applause. This was a true testament to the power of his playing and its hold on the audiences in Shanghai. Weatherford was indeed a very talented musician and not just some novelty act. In 1923, He had honed his musical virtuosity playing alongside Louis Armstrong in Chicago. Weatherford, an imposing figure at over 6 feet tall with huge hands, played with an amazingly hard-hitting left-hand banging out chords in a percussive manner that is characteristic of stride-style piano playing, while simultaneously gliding his right hand fluidly and effortlessly over the piano keys in the middle to upper register of the keyboard. Not only was this style of playing velocity-forward, but it also had to be a thrill to watch for audiences accustomed to a more genteel concert performance. Weatherford was so in demand that he often had three different gigs on the same night; he shuttled from performance to performance earning multiple paychecks a week. To keep up with the demand of jazz and other variety acts, Weatherford was tasked by the owners of the Canidrome, Tong and Vong, to go to the U.S. to hire more musicians and dance acts. Weatherford returned with several musicians including trumpet player Buck Clayton who traveled to Shanghai

![Figure 4. Shanghai, September 7, 1938. “Leaders of the Band.” From left to right: Jimmy Carson, Andy Andico(Filipino musician), Buck Clayton and Earl Whaley. All pictured were leaders of their respective jazz bands in Shanghai. “Earl Whaley’s Seattle-based jazz band, the Red Hot Syncopators, played in Shanghai clubs from 1934 until 1937, and continued to perform until he and others from his band were imprisoned by the Japanese Army between 1941 and 1945.” MOHAI, Collection on James E. Adams family, [2016.84.2.9]](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fcdn.sanity.io%2Fimages%2Fneqqlok6%2Fproduction%2Fc434541ce47301b53accf3dbab28294ecfbd739c-800x476.jpg&w=3840&q=75)

Figure 4. Shanghai, September 7, 1938. “Leaders of the Band.” From left to right: Jimmy Carson, Andy Andico(Filipino musician), Buck Clayton and Earl Whaley. All pictured were leaders of their respective jazz bands in Shanghai. “Earl Whaley’s Seattle-based jazz band, the Red Hot Syncopators, played in Shanghai clubs from 1934 until 1937, and continued to perform until he and others from his band were imprisoned by the Japanese Army between 1941 and 1945.” MOHAI, Collection on James E. Adams family, [2016.84.2.9]

with his wife in 1934. Clayton played in the house band fronted by Teddy Weatherford at Shanghai’s most elite, first-tier club the Canidrome.

In addition to Weatherford and Clayton, other Black musicians from the West Coast, particularly Seattle, would help fill the soundscapes of Shanghai. Band leader and saxophonist Earl Whaley, brought members of the American Federation of Musicians’ (AFM) Local 458, the first All-Black unionized musicians group from Seattle in the early 1930s. The 458 became the Local 493 in 1924 and by the early 1930s even began accepting other ethnicities on their rolls Whaley and his band “The Red Hot Syncopators” included other 493 members—Palmer Johnson on piano, Wayne Adams on baritone sax, Earl West on guitar, Oscar Hurst on trumpet, Fate Williams on trombone and Punkin Austin on percussion. Bassist Reginald “Jonesy” Jones would join the band later after a stint with Buck Clayton’s Band at the Canidrome(See Figure 4) Whaley’s Syncopators were the house band for the St. Anna Club, a third-tier dance hall in the International Settlement, which also hosted the all-jazz radio station XQHA. A 1934 advertisement for the St. Anna Dance Club in the Shenbao writes in large bold font “Earl Whaley’s Black Band” and “Dance and Tea Party opens every day at 6 pm. This lower-tier dance club catered to the Chinese middle class, so it would follow that Whaley’s group was playing a mix of standard jazz dance tunes and Chinese folk songs—yellow music. Whaley’s band enjoyed relative success in Shanghai and Tianjin until the Japanese invasion of Shanghai in 1937. The African American musicians who did not leave China after the Canidrome incident in Fall of 1934 found themselves eventual prisoners in Japanese internment camps at the start of the second World War. In addition to African American men, Black female musicians also figured prominently in the Shanghai jazz scene. The multi-talented singer, dancer and instrumentalist Valaida Snow, who W.C. Handy, the self-titled ‘father of the Blues’ once called her the second best trumpet player in the world, was probably one of the world’s most gifted musicians most people have never heard of, mainly because she spent much of her career touring overseas, especially

Figure 5. Valaida Snow at St. Anna Ballroom, Shenbao Chinese newspaper, Dance Club Advertisement.

Europe. Contemporaries and a rival of sorts with Josephine Baker, whom she costarred with in composer Eubie Blake’s and lyricist and dancer Sissle Noble’s 1924 Broadway production In Bamville, later called Chocolate Dandies. Though Chocolate Dandies was a successful follow up to the popular Shuffle Along(1921), Snow and Baker both received favorable reviews for their performances. Valaida had a significant run in Shanghai. She spent a little over two years with Jack Carter’s band in China from 1926 to 1928 playing first in the Plaza Hotel and then The Plantation earning close to $100 USD a week She was not only a great trumpeter, but also a talented singer and dancer whose shows were electrifying. Snow’s name appears in a 1934 Shenbao advertisement (see Figure 5) stating she would be performing at the St. Anna Dance Club in March 1934. The ad’s title in bold, large print reads “St. Anna, Black Songs and Dances … Appearing are “Valaida” and “Alice,” internationally known ladies of Black dance and song.” The center image appears to be two people in Blackface performing what looks like the Charleston dance. Again, Blackface and/or Black people appear in Chinese media as synonymous with music and dancing—historically professions in China that were equated with prostitution and moral depravity. As a woman singer in a male-dominated profession coupled with playing an instrument that also carried certain sexual connotations from the male gaze, Snow was not immune to the exploitation by industry powers and patriarchy, but her decision to reside mainly in Asia and Europe may have provided her with greater income and respite from the more overt racial tensions in the U.S. to sustain herself. Akin to other early Black women singers of the 1920s and 1930s, Valaida Snow also embodied what Angela Davis calls, “quotidian expressions of feminist consciousness. That is to say, Snow’s music and performances also expressed a certain Black woman’s poor and working class perspective that is determined and informed by race, class, gender and sexuality. For her final number at the end of her sets, Snow would play a vigorous trumpet tune and then run and slide into the audience on her knees gyrating through the crowd. Her theatrics never failed to elicit a roar of excitement from the crowd, even in elite establishments such as the Canidrome in Shanghai. With this freedom of expression in music and in the movement and control of her body, Snow exhibits not only a resistance to the established social norms, but an aggressive ownership of her sexuality on display.

Furthermore, another result of African American musicians clustering in Shanghai in the 1920s and 1930s was an extension of not only the black music aesthetic, but its concomitant social and cultural practices. There is a long tradition within the African American artistic communities for caring, nurturing and tutoring those invited into the musical circle of communion. Through these musical apprenticeships, Leonard Brown, ethnomusicologist notes,

You have to be invited … Much of this music was rooted in practices of the African ancestors, and often reflected adaptations and innovations resulting from black American life experiences. Acknowledgement of life’s difficulties and themes of “perseverance”, “resilience” “hope” and “freedom” can be found in the music … musicians had the responsibility of determining to whom, when, and where this knowledge would be passed” And with it one entrusted with such knowledge must know how it should be shared

Notice there is no mention of any requirement of race. This fellowship was open to all. Furthermore, Fishlin and Heble, echo these sentiments, stating, “the formation of alternative community structures that link improvised music with-… liberatory cultural practices. This most important socio-cultural function of the Black musician was extended into China. The inherent responsibility to disseminate the knowledge of jazz and foster community represented a paramount tradition. And thus sharing the “black cultural aesthetic”, so that the individual(s) invited to partake in the tutelage and instruction could harness the lessons and gain mastery over the musical vocabulary and syntax to express one’s own personal sound. At the outset, a musician started with mimicry and at its best ended his or her career with their own musical voice able move the tradition to new configurations, based in part, on an individual’s own unique personality and sociocultural environment. This knowledge was also given with the caveat that the recipient of the invitation was to continue the tradition and circle with other worthy candidates. In this regard, it is not difficult to imagine Black musicians in Shanghai like Teddy Weatherford, Earl Whaley and Buck Clayton, carrying out this duty for a number of the international musicians living and playing in the city.

Nanri Fumio, a Japanese musician playing in Shanghai in the 1930s, who would eventually gain fame in his native country as the “Satchmo of Japan” remembered Weatherford coming to hear him play. “He[Weatherford] asked me “Who’d you learn from?” and when I said “Louis Armstrong’s records”, he said, “I’ve played with Louie. Come over to my hotel”… He showed me blue notes and tenth chords. It was the best lesson’ It is likely that the other African American musicians also spent time when they were not playing seeking out different venues to hear live music. Besides being practitioners, they were also fans of the music and would have been keen on hearing others play not only jazz, but searching for other captivating sounds as well. It would not be uncommon in the African American musical tradition to pass along knowledge and “pointers” to other musicians, especially foreign ones, who demonstrated an interest in jazz. In some ways, Weatherford’s visit to Nanri’s session is a testament to his interest in seeking out other musicians to take in the sounds of his new environment and his willingness to offer his support and tutelage to those deserving. As to Weatherford’s query to Nanri, “who’d you learn from?” was Weatherford’s way of eliciting information about Nanri’s musical pedigree and background. Weatherford statement about his playing with Armstrong announces his credentials. And in that way informing Nanri that he could be Weatherford’s pupil or that he could become his acolyte or disciple in the ways of jazz. Nanri’s appreciation of the lesson as being “the best” also helped create and perpetuate the mythology around Shanghai as the preeminent destination to learn “real jazz” among Japanese musicians. For Weatherford, this experience of seeking out, finding and listening to other talented or eager musicians and offering his experience and wisdom of the music was not just a one off. This was a tradition that was passed down from musician to musician at every location, every stop one found him or herself. Buck Clayton, who subsequently held down the lucrative Canidrome job was most surely performing the same functions. It is also quite plausible that white Russian musicians such as Oleg and Igor Lundstrem, who performed at the famous and opulent Paramount ballroom in the 1930s, exchanged music with their black counterparts playing at other venues in Shanghai

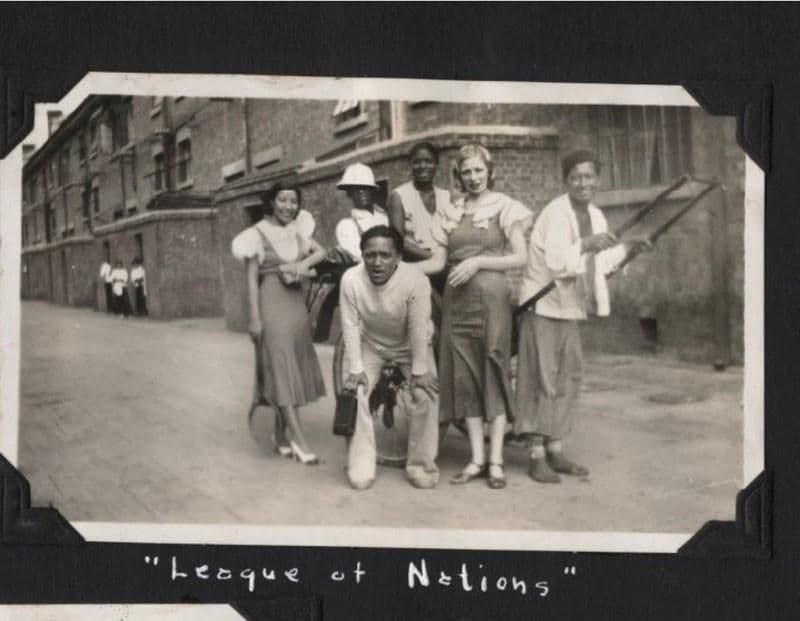

Buck Clayton took over band leader duties from Teddy Weatherford in 1934. For Clayton and his band members Shanghai was a place where during the middle of the Great Depression they lived very opulent lifestyles sheltered from most of the depravity of the times because of their purchasing power in China. Many in the band had all their clothes tailored, took up horseback riding, and enjoyed the equivalent of a jet set lifestyle in an international community of musicians and dancers. Russian, Filipino and Japanese musicians, dancers and other expatriates were regular friends and acquaintances during work and leisure time. In one group photo, the caption includes the title ‘League of Nations,’ the precursor to the oft used ‘United Nations’ moniker to refer to a diverse group. (see Figure 6).

The good times in Shanghai did not last long as the specter of racism was used to force Buck Clayton and his Harlem Gentlemen band from their posh position

Figure 6. “League of Nations.” Derb Clayton(left) with a host of international friends in Shanghai circa 1934-1937. LaBudde Special Collections, UMKC University Libraries.

in the Canidrome. One Fall night in 1935, a former white American Marine, Jack Riley instigated a fight with Buck Clayton over a perceived racial slight that embroiled the entire band into a confrontation during one of their sets at one of the most prestigious clubs in the city. The ensuing legal battle saw Clayton and his fellow band members ousted from the Canidrome with the threat of further violence if they did not comply. One scholar argues that the incident was an elaborate scheme by the club owners to break the lucrative contract of the band. In fact, once fired Clayton and his band move to the Casanova Ballroom managed by the same group at the Canidrome. Whether or not the management group was racist or that Jack Riley indeed took umbrage at Black musicians playing and dancing in such close proximity to white dancers is less important to the fact that race, particularly the American strand, was employed to great effect to marginalize and exclude the band for economic and/or social reasons.

The Riley incident not only reinforced the colonial and racial hierarchy of the American regime, but also delimited the contours of the space within the international concession betwixt and between the Chinese elite and commoner. The demotion of these jazz superstars, if you will, to secondand third-tier jazz venues quite possible served as disciplinary action by the white power structure or even by the Chinese owners of the club who did not wish to continue to pay top rates to Weatherford, Clayton and the other African American musicians. Conversely, by leaving the Canidrome to play at the Casanova Ballroom this event also had the effect of disseminating the music to a vastly different clientele—working-class Chinese. This change in audience forced Clayton and his musicians to incorporate Chinese Folk music into their repertoire, something Clayton found interesting and required a minimal amount of effort to transcribe songs from Chinese to Western musical notation During this time, Li Jinhui, the founder of Chinese Modern Music (shidai qu) was responsible for producing a great deal of the periods greatest female singers and actors, such as Zhou Xuan. While there is no evidence that Li and Clayton ever met or collaborated, it would be remiss not to consider the possibilities of both men having had some tangential musical overlap at the least in the form of passive or active listening to a performance, practice or jam session. Given the popularity of jazz in Shanghai, there had to always have been musicians in the audience listening closely to performances by the best jazz musicians in Shanghai that were now playing in a cheaper more accessible club for the Chinese masses. It is plausible to assume that Li Jinhui could have been among those in the audience.

While the silence in the archive of a direct link between African American and Chinese musicians is palpable, there are no records, as of yet, of Chinese musicians discussing lessons they received from the likes of Weatherford, Clayton or Whaley or even pictures of the musicians socializing with their Chinese counterparts, but we can nonetheless be fairly certain that these exchanges took place at least via technologies such as films, phonograph records, radio and live music venues for which there were many in Shanghai. We also hear the distinct traces and definitive impact of the music of those Americans in the songs of some of the Chinese singers and musicians as well as deduce from the advertisements of performances, movies with jazz themes and/or vignettes, and the writings of Chinese music critics the affective impact of this unique form of music on the Chinese populace.

Zhou Xuan, nicknamed the golden voice, was arguably the most famous Chinese singer and actress in Shanghai by the 1940s. Li Jinhui’s most famous protege, Zhou recorded over 200 songs and acted in over 40 movies from the 1930s to 1940s. Since the 1920s, Chinese musicians had been acquiring the rudiments of blues and jazz forms through transcribing film scores at movies, listening to technologies such as phonograph records, and undoubtedly attending live performances of African Americans bands in one of the Shanghai nightclubs like the St. Anna. Zhou Xuan’s recording of Two Roads (liang tiao lu shang) is set to a standard AAB or 12-bar blues format. The phrasing and elements employed in this song is unlike most of the other tunes in Zhou’s repertoire. The length of the song, for example, diverges from the 12-bar blues in that it is extended to a 26-bar song. The two A parts both have 8 measures instead of the usual 4 and the final B has 10 measures. Theoretically, this “extended Blues” format had to be lengthened to accommodate the lyrics of the song in Mandarin Chinese—a monosyllabic language where commonly one Chinese character receives one syllable and equals one word, but also consists of multiple character compound combinations to form new words. The syntax of the Chinese language called for a longer song to express a meaning that perhaps proved difficult to contain within a 12-bar blues written in English. The song starts with a kind of slowed tempo boogie-woogie walking bass line. Boogie-woogie was a style of piano playing popularized in Chicago in the late 1920s by Blues pianists such as Meade Lux Lewis and Teddy Weatherford. The content of the song concerns the duality of the “progress” of modernity juxtaposed against the traditional.

Zhou sings about two different roads she travels—one during the day and the other at night. The road traveled in the morning is a bustling modern scene that appears dangerous and hazardous to pedestrians. Zhou sings in the first A part, “The road that I walk on in the morning, I can only see pedestrians, and I can only see cars; with a beating heart I anxiously stumble forward.” Here Zhou’s anxiety surrounding the exigencies of modernity highlight her extreme trepidation, especially as a woman, she felt in the large modern Shanghai landscape not only during the interwar years, but also in the post-World War II environs of 1947 when the song was recorded and with the resumption of the Chinese Civil War. In the second A section, Zhou sings “The road I walk on in the evening, I can only see the light, I can only see the moonlight, with an empty heart, I calmly look forward.” The B section starts— “The road is so desolate, and the other road is too intense, I cannot find a better place, I am on these two roads every day.” Zhou seems to feel resigned to an existential sense of helplessness that there is no escape from either path and that she must confront whatever lies ahead.

Yan Zhexi, who was a popular songwriter and visual artist wrote “Two Roads. It is important to note that this song is a clear example of the conscious use of and reference to Blues and jazz musical elements. The B section of the song makes use of the fourth chord which is a signature of the Blues format. Zhou also executes sliding and bending pitches of 5ths and 7th (blue notes). The musical totality of “Two Roads”, however, does not match the sound of the music it attempts to mimic, “… these stylistic references constitute a type of parody. They are quotations in a new context. The boogie-woogie figures, for instance, do not achieve the flexibility or kinetic energy of the exemplary boogie-woogie pianists. They have been decelerated, simplified, stripped down. The choice to use a blues/jazz format to express the modernity of the song’s existential subject matter is noteworthy. Using Blues to talk about issues that were perhaps taboo in public discourse was of course common in the American Blues tradition. Perhaps Zhou was hiding the expression of her anxiety, critique of modernity, and the political situation in plain ear shot of authorities bundled in a foreign-style to escape the repercussions of the two rival governments. The musicality of Zhou’s Two Roads, however, belie the outdated state of the Shanghai music scene in the mid 1940s due to World War II. Shanghai was no longer at the cusp of new Black music being imported via African American musicians. By the mid 1940s, a new generation of musicians in Harlem were evolving and revolutionizing the harmony of jazz with the creation of Bebop characterized by its fast double time flurry of sixteenth notes and harmonic versus melodic improvisation. Zhou’s song is rooted in an earlier form of jazz and blues that still co-existed, but was no longer avant-garde. One way to view Zhou’s Two Roads is one of stagnation, employing musical tropes that were hackneyed and antiquated. This perhaps speaks to the harbinger of a new era that would come into fruition and represented a mode of musical bifurcation between the Nationalists who would soon flee to Taiwan as the Chinese Communist Party liberated China. The creation of Canto and Mandopop in Hong Kong and Taiwan respectively take shape directly from this merger of Black and Chinese sounds. There is, however, another way to look at Zhou’s music in a different context. A 1949 jazz “fake book” (a compilation of various sheet music of standard tunes) published in Shanghai using traditional Chinese musical notation illustrates this point The fake book contains many songs popular in Shanghai in the 1930s and 1940s. What is interesting about this book is the number of Chinese folk songs that have been included. Many of the songs notations explicitly note how they are to be performed. Some dictate the musicians play with a Tango “feel” for instance. One of China’s most famous folk tunes, The Flower Drum Song (not to be confused with the 1950s Hollywood version) is written with the notation to play with a Samba feeling.

Both the Samba and Tango originated in Brazil and Argentina respectively via rhythms from West Africa played by Afro-Brazilians in favelas in Rio de Janeiro and those of African descent in the working class neighborhoods near the Plata River in Buenos Aires. Jazz musicians were already quite familiar with sounds from Latin America via the trade routes between Havana and New Orleans in the late 19th century The jazz and Samba integration that would become the Bossa Nova craze by the mid20th century was perhaps already taking place in Shanghai in the years before the Communists came into power evinced by the number of traditional songs that have been transformed into different musical styles, especially jazz. Consequently, Zhou’s Two Roads, becomes a metaphor for the trajectory of the music—one that looks to incorporate and embrace other traditions into itself and the other to look back on halcyon notions of the traditional folk song that can be expressed in a similar format, but using different language in the name of nation-building and social realism. For instance, The Communist Party’s use of this widely popular folk tune, The Flower Drum Song, was adapted to employ as a patriotic device to foment anti-Japanese sentiment during World War II. The Flower Drum Song, much like the American Blues articulates not only, the depravity and horrors of the human condition, but also provides the necessary impetus to overcome and transcend life’s limitations. The failure of Chinese intellectuals to interrogate the parallels of these folk art forms to a logical conclusion is telling, especially, in light of the figure of Paul Robeson who sustained intimate cultural and political ties with China. Furthermore, Robeson had also been theorizing the interrelatedness of these folk musics and history

The Chinese cultural production of jazz critiques paralleled and reflected some of the same reductive criticisms of early and mid20th century white critics from modern metropoles from New York to Istanbul. These included false perceptions of the music’s simplicity and decadence that were seemingly responsible for corrupting the morals of society and appealing to the base and “emotional” instincts of humankind. In this vein, Black music and Black people simultaneously represented modernity and its polar opposite—primitivity. In the United States, the antecedent of jazz music, ragtime achieved popularity with mainstream American audiences between the 1890s and 1920. The genre originated from Black folk music and was popularized via minstrel blackface performances and songs which were often always associated with a denigration of Blackness. Ragtime was often described as being “ragged” in sound and in reference to the physical appearance of those who played the music A great deal of the early reception of jazz in America in the 1920s and 1930s was not flattering. Dr. Frank Damrosch, director of the Institute of Musical Art, later known as Julliard School of Music, writing in a special edition of the Etude magazine in August 1924, titled “The Jazz Problem” wrote “If jazz originated in the dance rhythms of the negro, it was at least interesting as the self-expression of a primitive race. When jazz was adopted by the highly “civilized” white race, it tended to degenerate it toward primitivity. We can only hope that sanity and the love of the beautiful will help to set the world right again and that music will resume its proper mission of beautifying life instead of burlesquing it.

There was also little ambiguity expressed in China in regards to the creators of jazz being Black as there was in other Asian spaces like the Philippines, where in the American colony, jazz was employed in the civilizing mission of the colonizer The presence of jazz and its inherent Blackness engendered a certain affective disposition toward the music that was expressed in the critical language and reception by Chinese intellectuals. One Chinese author, Fang Xin writing in 1937 lamented that, “components of jazz music is usually barbaric and depressing, which also proves that this music definitely originates from Black people … Essentially, it was the intelligence of the white race and the anesthetizing nature of jazz that brought harmony to the misery of Black people’s lives. For this author, whose identity may be lost to the pages of history due to the extensive use of pen names during the era, the music seems to inherently embody a morose pathos that is constitutive of Blackness The quality of the music “proves” the Black origins. Jazz becomes a musical metaphor for primitivity and a trope for the melancholy. Jazz in China, like other Black music in America, becomes racialized Why do these putative essentialisms of jazz music “prove” its Blackness? Jazz music in its totality is capable of a myriad of emotional expressions, sadness, just one of many, but the author here is fixed on pitting Blackness in opposition to “the intelligence of the white race” whose presence allows for a dialectical resolution of the two forces. This narrow reading of jazz and Black people delimit the possibilities and multiplicity of emotional qualities that are expressed in this Black art form. The people and their music also become marginalized in this critique as emotionally irrational beings capable of only a primal expression in opposition to the rational “intelligence” of whites. This concretized metaphorical critique of Blackness stands in for racial hierarchy of the modern world. Only the “intelligence” of whiteness, presumably due to the enslavement and/or subjugation of Black people “brought harmony” to the preexisting doldrums of Black life.

Embedded in this critique is also a justification or acceptance of the forceful subjugation of African descendants by Anglo-European powers without any reflection of China’s own parallel issue with European transgressions. Another Chinese writer asked, “Why does real jazz music, in other words, the kind that doesn’t lose the essence of jazz, only exist in America, and why can only Black people like Duke Ellington play such superior and touching jazz? It is interesting to note that if it were not for the movie Check and Double Check, (Ellington and his band received a contract with a movie studio to appear and perform) he and his band would have probably been a part of the group that Teddy Weatherford was tasked with taking back to Shanghai instead of Buck Clayton. Who knows if Ellington would have stayed in Asia or returned to the States during the interwar years and how that would have impacted his career trajectory? That a Chinese music critic, however, was writing about him attests to his global popularity and fame as one of the first American global pop stars. The author suggests that the authenticity of this jazz affect is something produced solely from the purview of Black people. It is this argument of charged emotion that is at once the source of the attraction and revulsion of the music.

The Chinese Left’s critique of jazz, while seemingly more sympathetic, also questioned the music’s capacity to be used in revolutionary work needed for nation-building in the new, future Chinese nation/state. In May 1942, Mao Zedong gave his influential speech on the proper role of artists and their cultural production in nation-building at the Yenan Forum On Literature And Art. Mao criticizes the state of literature and the arts:

Many comrades like to talk about "a mass style".(sic) But what does it really mean? It means that the thoughts and feelings of our writers and artists should be fused with those of the masses of workers, peasants and soldiers. To achieve this fusion, they should conscientiously learn the language of the masses. How can you talk of literary and artistic creation if you find the very language of the masses largely incomprehensible?

By extension, this critique was also applied by leftist writers to highlight the incompatibility or inappropriateness of the musical language of black music to the Chinese situation. Despite the fact that jazz was quintessentially a music that was conceptualized and produced largely by those originating from the poor, exploited working-class masses in the United States, jazz is described instead as an “erotic” and “emotional” music in contradistinction to more acceptable forms of music that could be used to further the Chinese liberation movement. One leftist writer clearly delineated the most useful modes of musical expression for China during the Republican Period:

The second is the erotic music we mentioned just now. Although this kind of music consumes emotions, it is still very popular, especially as the middle-class people’s hobbies. Most of this music talks about the love of men and women. the most appropriate description of this music is “demoralizing.” The third kind of music is the new music advocated by Nie Er and Xi Xinghai. this music reflects the reality, so that people who listen to music feel a force. Its style is healthy. Anti-Japanese songs and folk songs belong to this kind of music

Additionally, the Chinese Communist dialectical and material historical critique of the music also fails in its attempt to accurately gauge the relevance of the music and its working class origins— relegating it to a lascivious bourgeois music.

Some people say, "you can understand a nation from a song and there is a good reason for this. Music reflects the life and feelings of a nation. Erotic music is a commodity. Its production does not originate from creativity, feelings or emotions. Its production results from the satisfaction of the vulgar taste of the lower middle classes. There are no emotions but the emptiness and anguish of one’s life. The new music has actual substance. It shows people’s feelings and demands. The new music is better than jazz, so we should get closer to it in the future. To make it a part of our feelings, because listening to healthier music can cultivate healthy feelings

What most of the Chinese critics did not seem to understand or value was that “jazz” a word that many musicians did not care to apply to their music, was the cultural function of its creation in a hostile and suppressive environment specifically by African Americans to meet their specific needs. Many Chinese critics elected to ignore or not investigate the fact that African American music was employed as a coping mechanism, a means of instilling hope, joy and celebration of Black humanity in a particular condition that otherwise forbade and disparaged it. Paul Robeson, the famous African American actor, singer, and activist understood these connections. Part of his life’s work was spent investigating the similarity between world folk music based on the pentatonic scale. The Chinese intelligentsia and public-at-large struggled, on the one hand, with an unwillingness to hear “jazz” on its own terms without resorting to discourses of simplicity and primitivism that belied a problem intellectuals in and outside of China would grapple with in one form or another continually for decades. By the early-1950s before the U.S. State Department deployed jazz and jazz musicians as an emblematic beacon of the creative genius of blackness under its egis and of the progressiveness of American society, the music had come to represent the worse of Western culture in China.

The case of jazz’s reception by intellectuals sympathetic to Nationalists before 1949 and subsequently by Communist authorities both before and after their 1949 national liberation were indicative of their mutual lack of understanding of the purpose and function of Black music. During a period when Chinese leftist intellectuals and musicians such as Nie Er were theorizing a political praxis for harnessing the power of Chinese folk songs to serve the nation, jazz, whose roots of blues were similar to those of the folk song traditions were marginalized. Again, Paul Robeson’s ideas, despite being incomplete and some may argue teleological, attempted to demonstrate a connection between the folk song traditions of Black America with those of China. Unfortunately, like jazz and its musicians, the importance of Robeson and his work are elided in the Chinese Communist Party’s racial interpretations and political exigencies of decolonization and the Cold War.

It would be remiss to assume that Chinese intellectuals of the time were unfamiliar with the value of studying folk music and culture and being able to make the intellectual connection between the two traditions in the same way Paul Robeson achieved. Intellectuals such as Hu Shi and Lu Xun, championed the study of the vernacular in Chinese culture, for which peasant folk songs were an integral component and extension of the New Literature Movement This is perhaps why Lu Xun acknowledged the significance of Black literature. An examination of folk song of Chinese origin and the folk tradition that is the Blues and Jazz details some of these similarities in subject matter and literary execution. Similar to the Blues, Chinese folk music can be categorized into themes dealing with love, suffering, and even salaciousness. One such popular song from Yunnan illustrates this sexual innuendo:

My love, you are a dragon roaming high above, I am a flower bush down below.

If a dragon doesn’t caper there will be no rain,

If there is no rain the flowers will not bloom

A popular Suzhou song reads:

At sixteen she is full of burning desire,

Two ivory breasts are visible underneath her red blouse

“My maid, you are like a big freshly steamed bun, I shall gobble you up tonight.

Another title, “Eighteen Touches” is even more explicit in its explication of sexual desires:

Fondling your breast with my hands,

Your breasts are like freshly steamed stuffed buns, Ai-ai-yo, ai-ai-yo,

Here’s a tit on the top,

Ai-ai-yo!

Caressing your bottom with my hands, Your bottom is as big as the blue sky, Ai-ai-yo, ai-ai-yo,

It looks like a painted face, Ai-ai-yo

These sexual metaphorical references to “the dragon,” “flower bush,” “rain,” and “steamed stuffed buns” are similar to the kind of referents used by Blues singers such as the Bessie Smith, widely considered the mother of the modern Blues, an African American folk music and precursor of jazz. Smith’s insinuations of sex have an equivalent tone and quality. Her song titled Need a Little Sugar in My Bowl is perhaps emblematic of this similar character:

Tired of bein’ lonely, tired of bein’ blue

I wished I had some good man, to tell my troubles to … I need a little sugar in my bowl

I need a little hot dog on my roll …

I need a little steam-heat on my floor …

Get off your knees, I can’t see what you’re drivin’ at It’s dark down there looks like a snake

Stop your foolin’ and drop somethin’ in my bowl

The usage of the double entendre and explicit references are present in both traditions. It is not happenstance to postulate how the Blues and jazz medium was suited musically to the Chinese folk song tradition. In a way, jazz became embroiled into a larger Chinese discourse on the appropriate nature of folk musics, that also included notions of Blackness, that relegated it to the periphery in among both Nationalists and Communists during Republican period. That scholars like Hu Shi found significance and value in folk traditions spoke to their inquiry of openness and possibilities during this period. The failure, however, of most Chinese scholars to critically engage and to commit to a more open and extended critique that examined the common linkages between Chinese and Black Folk music was a lost opportunity in favor of reductive commentaries.

By 1954, The CCP effectively rooted out the cabaret culture for mass public consumption (elite Party members such as Mao still held private dance parties replete with jazz music) Jazz was labeled as “reactionary” music. Chen Yulin, who was a trumpet player during the halcyon days of Shanghai’s Jazz Age lamented the fact that after National Liberation he was rehabilitated and jazz was vilified. “When we watched Chinese films,” he remembered, “whenever the enemy appeared, there’d be jazz music in the background. Jazz would not appear again for the masses in mainland China until the Open and Reform of the 1980s that saw the importation of new technologies such as the cassette player and jazz musicians global movement to China in the early 1980s and 1990s.

One such group was the Mitchell-Ruff Duo, at the time the oldest jazz duo group in the United States. Pianist Dwike Mitchell and French horn and bass player Willie Ruff had been playing together since the 1950s and opened for such illustrious jazz bands as the Count Basie Orchestra and Duke Ellington. Willie Ruff personally raised money to travel to China in 1981 and spent six months learning Chinese, so that he could speak directly to his audiences about the history of jazz music. Mitchell and Ruff were invited to China by Tan Shu-chen, then deputy director of the Shanghai Conservatory of Music, whom they had met the previous year in Boston Mitchell and Ruff gave a master class to students and professors at the Conservatory.