“Where I’m Bound”

Come and go with me to that land Come and go with me to that

land Where I’m bound

Come and go with me to that land Come and go with me to that

land Where I’m bound

Ain’t no welfare in that land— Aint no begging in that land Aint

no hunger in that land Ain’t no workers in that land Nothing but

joy in that land

From the National Welfare Rights Organization

The abolition of a society that could have prisons, that could have slavery, that could have the wage.

—Fred Moten and Stefano Harney The Under Commons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study

The proletariat betrays its instincts and misunderstands its historic mission by allowing itself to be perverted by the dogma of work. The punishment has been harsh. All individual and social misery is born of the passion for work.

—Paul Lafarge The Right to Be Lazy

Radical scholars have long emphasized the profoundly transformative effect social movements—and other collective mobilizations—have on peoples’ beliefs about the world One particularly fruitful contribution to this conversation is Robin D.G. Kelley’s concept of “freedom dreams. In an eponymous book, Kelley explores collective mobilizations that do more than just make concrete demands, but are richly imaginative political projects that alter how we see and understand the world, challenge perceived limitations of what might be feasible or desirable, and shift our sense of possibility. Examining instances of freedom dreams as they appear in the Combahee River Collective, mobilization for reparations, and Black nationalist projects, Kelley asserts, “revolutionary dreams erupt out of political engagement; collective social movements are incubators of new knowledge … new theories, new questions. I draw from Kelley’s example here to examine the freedom dreams of the welfare rights movement (WRM) in particular, how activists sought to confront and transform our understanding of one of society’s most revered and hegemonic institutions: wage work. Centered on the movement’s archives, I explore the WRM’s visionary—if sometimes polyphonic—critiques of wage work and aspirations for a world with “no workers” articulated in the epigraph above, as an example of an “antiwork” freedom dream. I trace how participants in the WRM critiqued work as an insufficient mechanism for addressing poverty, and highlight their alternative solution: income decoupled from employment, in the form of a guaranteed income for all enshrined by “the right to live,” freed from the compulsions of waged labor. I emphasize the commonalities the WRM’s articulations share with established antiwork theorists in order to intentionally underscore welfare activists as inventive public intellectuals and radical visionaries whose sophisticated theoretical output enriches existing bodies of political and social thought

Like Kelley, I focus on this visionary freedom dream not because the movement was successful in their antiwork aspirations (spoiler alert: they were not), but as E.P. Thompson reminds us, “[i]n some of the lost causes … we may discover insights into social evils which we have yet to cure. The contemporary reality is that working class people cannot rely on employment for their well being, financial or otherwise Within this context, we may view welfare activists—the frustrations and challenges they faced, as well as the alternatives they proposed—as modern day Cassandras, signaling not only the problems of a society that emphasizes work as the solution to most of its ills, but also prescient in the alternatives they imagined.

The Welfare Rights Movement

Much is known about the welfare rights movement (WRM): the ardent, grassroots struggles waged in the mid 1960s to 1970s by mostly Black welfare recipients against intrusive caseworkers, unjust benefit cut offs and inhumane sterilizations. They sought to compel the federal government to overhaul the stingy atomized welfare system and institute a guaranteed income Careful scholarship has documented the amalgamation of disparate grassroots efforts into the National Welfare Rights Organization (NWRO), and their local chapters who fought for more generous benefits, dignity, and consumer as well as the internal conflicts that plagued the movement Additional scholarship has examined the innovative, but often unsuccessful efforts of affiliated antipoverty lawyers as they attempted to replicate the Civil Rights Movement’s remarkable litigative achievements One feature of the movement that has not received comprehensive attention is its ambitious “antiwork” politics, encapsulated most succinctly in the above epigraph as an aspiration for a world with “no hunger,” “no workers,” and “nothing but joy.” Existing scholarship on the WRM has largely overlooked this leitmotif, emphasizing instead the organizational ideology of motherhood and domesticity as the central perspective animating the movement’s pursuit of a guaranteed income There are some exceptions to scholarly narratives that emphasize fidelity to a gendered division of labor: Felicia Kornbluh underscores that the movement’s “overarching goal was to establish welfare, or a minimum standard of living, as a citizenship right and human right. In contrast to much existing scholarship Kornbluh emphasizes that “[t]his minimum was to be based neither on wage work nor on any other specific contribution to the state—often, not even on motherhood—but was conceived as a universal ‘right to live. Kornbluh’s assertion however, has been insufficient to settle the question once and for all, as later scholarship often resorted back to insisting that gendered ideologies dominated the movement’s goals In a recent article, Frances Fox Piven and I examine the other activities through which welfare activists derived meaning: decentering domestic labor, and highlighting the importance of community activism as primary sources of identity and meaning making. While we briefly examine the movement’s antiwork politics in that article, a systematic examination of the movement’s sophisticated antiwork politics remains necessary to give welfare activists’ profound interventions their proper due.

What Are Antiwork Politics?

One question gaining greater resonance in this era, encouraged by fears of automation, technological unemployment, and persistent precarity faced by employed people, is whether in rich societies it is reasonable for working class people’s livelihoods to be entirely reliant upon employment Well before the Covid-19 pandemic imbued this question with a particularly dire urgency, a subset of leftist thought known as “antiwork politics” gained notice for challenging the capitalist insistence on employment as the panacea to most social problems Antiwork politics are defined by French theorist Roland Simon as “the aspiration that work no longer be the condition nor the center of people’s lives Far from advocating total indolence, as many fear when they hear the (admittedly challenging, and perhaps misnomer) term “antiwork,” Simon emphasizes the theory as a mobilization against the portion of people’s lives that work occupies, as well as an opposition to the fundamentally coercive nature of an institution that demands, in the words of welfare rights activists, that people “work or starve.

While many antiwork advocates recognize the important feminist intervention that what counts as “work” and therefore worthy of a wage, is too narrowly delineated under capitalism, rather than seeking to expand the category of work to be more inclusive, antiwork advocates seek to rethink an institution which demands that people demonstrate their productivity in order to be deemed worthy of survival This is both a pragmatic and ideological intervention, as many have argued the apparatus necessary to police eligibility for means-tested programs that determine what work is legitimate or who has performed enough of it renders such programs extremely expensive, invasive, and inefficient Antiwork advocates assert instead, that money would be better spent giving it to people who declare they have a need, rather than generating enormous administrative bloat to assess whether one has adequately contributed to society to merit existence.

In a logic similar to that of police and prison abolitionists, proponents of antiwork politics see the unjust aspects of the wage relation—exploitation, poor health, harassment, persistent poverty, to name a few—as intrinsic to the institution and therefore incapable of being addressed by the reforms which have been proposed and enacted since nearly the inception of capitalism Rather, than looking to reforms for answers, as Simon insists, antiwork politics “situate unemployment and precarity at the heart of the wage relation, which necessitates its being called into question. Many of those interested in antiwork politics today argue that, contemporary work conditions—defined for large portions of the workforce by low pay, sporadic schedules, unfulfilling activities, and little security or room for advancement—necessitate reevaluating and refusing the hegemony of wage work.

Feminist philosopher Kathi Weeks takes a more expansive approach in The Problem with Work, identifying the project of antiwork politics as seeking to undermine “work’s domination of the times and spaces of life and of its moralization, a resistance to the elevation of work as necessary duty and supreme calling. Challenging the ideological power of work under capitalism is one of the key interventions made by antiwork theorists and practitioners, and as I will later argue, a particularly incisive component of the welfare rights movement’s refusal to seek ameliorative reforms to merely soften the compulsion of work.

In their theoretical and pragmatic interventions into the failures of “the work regime, antiwork thinkers underscore the irrationality of requiring employment to bear the burden of addressing most social problems—how people meet their material needs, derive their self-worth, secure health care and develop social networks. Far from actually achieving these objectives, the obsession with wage work has resulted in incredibly short-sighted, and destructive decisions. Some stark examples include former President Barack Obama’s justification for failing to implement a single-payer healthcare system on the grounds that a large number of administrative jobs would be lost at health insurance companies; or construction trade unions fighting for culturally and environmentally catastrophic oil pipelines in the name of job creation Antiwork thinkers point out that a fidelity to job creation generates a false bind between addressing issues such as universal healthcare, climate catastrophe, or migrant crises, and sufficient employment. In recent years, antiwork politics have garnered increased relevance as scholars and activists attempt to understand and address the daunting confluence of climate change, economic inequality, mass incarceration, automation, and global health pandemics, proposing that a guaranteed income decoupled from work would provide crucial steps towards addressing many of these crises.

Although they offer provocative insights into the problems with work and a work-centric society, texts on antiwork often remain in the realm of highly abstract normative philosophy; they provide few clues as to how, or even if, the struggle against work takes shape in practice Examining the small scholarly record of antiwork politics one could easily believe that they exist primarily as radical intellectual theorizing, or as atomized, clandestine, individualized or even “sloppy” acts, rather than ever manifesting as a collective political project Viewing the WRM through the lens of antiwork politics provides a concrete example of a sizable historical social movement that embodied the radical antiwork aim to separate the need to work from the right to live.

Scholars of the WRM can be forgiven for overlooking the movement’s antiwork politics when the theme remains similarly absent from scholarship at large, especially the fields of social movements and labor studies where one might most expect to encounter it. Indeed, scholarship on social movements seeking economic justice overwhelmingly emphasizes access to, and improvement in, employment opportunities. These disciplines, focusing almost exclusively on mobilization for more and better work, have yet to recognize antiwork politics as a legitimate or even possible political aspiration. As Saidiya Hartman notes of other insurgent and utopian longings, antiwork politics—in the welfare rights movement, and elsewhere—“has not only been overlooked but is nearly unimaginable. Anthropologists Jean Comaroff and John Comaroff confirm what a review of existing literature indicates: “We—scholars, politicians, pundits, people at large— seem unable to think beyond a universe founded on mass employment.

Although many of the unique analytic contributions of antiwork politics, outlined briefly above, appear in the welfare rights movement’s oeuvre, in this essay I closely examine three main themes through which the NWRO articulated their antiwork politics: First, they rejected the premise that jobs can solve poverty, and in doing so, situated problems with work as central to the institution and therefore irreformable Secondly, they challenge the moralization of the work ethic, and finally, and perhaps most uniquely, they appeal to a racialized class consciousness to develop their antiwork analysis. Throughout these different analyses the NWRO insisted on guaranteed income for all, decoupled from work as their desired solution, refusing the call for expanded, improved employment opportunities, or the continuation of a gendered division of labor enabling women to stay home while men worked.

As perhaps the largest and most cohesively articulated antiwork social movement to date, the WRM holds crucial importance in deepening our empirical understanding of antiwork politics, the pursuit of income decoupled from work, and what motivates its advocates Additionally, analyzing the WRM thus, situates antiwork politics as an overlooked component of the rich and variegated legacy of the Black radical tradition providing a counter narrative to the assertion that full employment and better jobs are the principle desires of Black movements

A Note on Methodology

Scholars of radical social movements, especially movements of the 1960s, have identified a trend of scholarship that trivializes, domesticates and “defangs” movements’ political visions, undermining the “vast sense of possibility” they generated As Michael Watts describes evocatively, studies of the era have

become so wrapped in cant and the worst sort of revisionism, so clouded by the admitted excesses and confusion of the times, so discredited by the defeats and reversals that followed the turmoil of 1968 … that it has become impossibly difficult to reclaim what was, and indeed what remains, so radical and relevant about the sixties

One source of this revisionism, critical scholars have noted, are narratives produced by former movement participants 30, 40 or 50 years later, which tend to imbue reflections on past beliefs and actions with the values of the present day. In these interviews the perceptions and values of the ensuing decades move to the foreground, while the cognitive maps, or “freedom dreams” developed at the time of the movement itself, if they are acknowledged at all, become hazier, perhaps even embarrassingly idealistic and therefore muted and downplayed For this reason, a number of scholars, especially those concerned with the radical political projects of the long 1960s have emphasized returning to the archival record—to the words, thoughts and images produced during the movement itself—rather than post hoc participant interviews. With these insights in mind, I intentionally rely on the movement’s extensive archives of primary documents in order to examine the WRM’s antiwork politics Many of the documents I analyze—pamphlets, newspaper articles, songs, speeches given at congressional hearings, internal documents and more, including the evocative song that begins this article—have been absent from the scholarly record of the movement until now.

The Welfare Rights Movement’s Critiques of Work

During the long 1960s, politicians, activists, and frustrated housewives alike identified expanding and improving waged labor as crucial to remedying the era’s problems, especially for African Americans and women For example, tasked with making sense of hundreds of riots that swept across the country in the late 1960s, the Kerner Commission concluded that high unemployment rates among African Americans was one of the prime causes of the era’s unrest and that increased access to good jobs were needed to remedy this One culmination of this era’s jobs-centric analysis was the 1967 Freedom Budget. Developed by economist Leon Keyserling and endorsed by notable civil rights activists such as A. Philip Randolph, Bayard Rustin and Martin Luther King Jr., the Freedom Budget sought to address the economic plight of African Americans, unequivocally asserting that ensuring the availability of well-paying jobs was central “The key is jobs,” authors of the proposal argued:

We can all recognize that the major cause of poverty could be eliminated, if enough decently paying jobs were available for everyone willing and able to work … What we must also recognize is that we now have the means of achieving complete employment—at no increased cost, with no radical change in our economic system, and at no cost to our present national goals—if we are willing to commit ourselves totally to this achievement

Proponents of the Freedom Budget believed there to be a clear continuity between New Deal programs, the Employment Act of 1946, and the Freedom Budget, which they envisioned as the ultimate fulfilment of the unfinished, and racially discriminatory promises contained in the earlier programs Early publications by the NWRO shared a similar perspective to the Freedom Budget, and demanded, “JOBS OR INCOME NOW! Decent Jobs with adequate pay for those who can work and adequate income for those who cannot. But quickly, as the NWRO gained a larger membership and political influence, it moved dramatically away from this demand, and developed an analysis of poverty that demonstrated a substantive break with this formulation

Jobs Don’t Solve Poverty

In 1970 William Whitaker, a graduate student studying the WRM, summarized the WRM’s distinct perspective vis a vis work, identifying its crucial ideological rupture from other movements, noting, “whereas the civil rights movement had attempted to open up the right to participate in the economic system of American society, in a sense welfare rights has sought to legitimatize the prerogative of persons to refrain from such participation and yet still receive sustenance from social sources. Whitaker’s interpretation, in this regard, was spot on: The WRM rejected the analysis proffered by the Freedom Budget, and many other contemporaneous social movements that jobs were central to ameliorating social problems, and that it might be possible to reduce economic insecurity with “no radical changes in our economic system.” Instead, for most of the organization’s tenure, the NWRO insisted that employment was not the solution to poverty and that it was impossible to remedy the plight of the poor with minor reforms because poverty was a necessary, and constitutive aspect of the wage system.

As an organization, the NWRO’s utmost priority was eradicating poverty. In numerous publications the NWRO sought to demystify prevailing notions of why people were poor, and what policy solutions might finally resolve poverty, challenging the ameliorative potential of employment. One pamphlet, which succinctly encapsulated the organization’s perspective and resonated with readers (as evidenced by its reproduction in local and national welfare rights organizations’ publications for many years) reads: “[the] NWRO recognizes that people are poor because they don’t have enough money. Poor people have never been able to secure enough income from the wages they earn to enable their families to live decently. Yet every man, woman and child has the right to live. Poverty, they insisted, contrary to most common perceptions and interpretations at the time, was not merely a temporary or remediable condition which arose due to a stagnant economy or discrimination, it was due to a lack of money, which employment, in their analysis, was fundamentally incapable of resolving. The NWRO frequently underscored that poverty was part and parcel of the system of employment for working people

The WRM’s emphasis that poverty persists despite or even because of employment, was featured frequently in their educational materials. One pamphlet posed the question “Why are there so many poor?” The answer:

Our economic system is structured so there is always a large number of poor people. The poor are needed to fill millions of low paying jobs that sustain many industries in our country. When industry needs them, the poor are called to work. When industry doesn’t need them, many people must go on welfare or survive as best they can. By always having more people than available jobs, industry is guaranteed all the cheap labor it needs

A far cry from the Freedom Budget’s assertion that poverty could be addressed by creating more jobs through minimal change to the economic system, the NWRO situated poverty and unemployment as essential to the functioning of the entire economic system. In this sense, the NWRO’s analysis of the centrality of unemployment more closely corresponds with Marx’s “reserve army of labor,” which he believed was so essential to capitalism that it functioned as the “lever of profit accumulation,” than a Keynesian, or New Deal perspective encapsulated by the Freedom Budget

Despite the ubiquity of demands for job creation or higher wages, the NWRO identified the solution to poverty as guaranteed income for all poor people, not just women and caregivers, decoupled from employment. A NWRO pamphlet explicates:

Is there a solution to the problem? YES! … A guaranteed adequate income plan would attack the root cause of poverty: a lack of money in a large segment of the population due to an economic system that thrives on cheap labor, high unemployment and the concentration of the country’s wealth in the hands of a privileged few

By situating poverty and unemployment as central, structural byproducts of wage work, the NWRO demonstrates one of the core analytic gestures of antiwork politics: to identify the problems with work as constitutive of the institution, refusing analyses that view them as merely frictions that can be ameliorated with reforms In these articulations we see the development of a crucial theoretical rupture from the Keynesian, or New Deal logic that animates many reformist approaches to work which, in much scholarship, has been designated the only conceivable perspective

Refining Their Analysis

In 1970, at the peak of the NWRO’s prominence, measured by both membership and influence, President Nixon proposed a major overhaul of the welfare system in a proposal called the Family Assistance Program (FAP) FAP would have allocated $1,600 a year in benefits for a family of four, contingent on numerous work requirements. This was a crucial moment for the NWRO to expose the undesirable ideology and alternatives animating Nixon’s plan, and to press for their own vision. Accordingly, the NWRO devoted much of the next few years to critiquing FAP, campaigning against it, and promoting their desired alternative The WRM was particularly invested in this issue, in part, because they saw FAP as a response, albeit insufficient, to the pressure their activism was successfully and demonstrably exerting their criticisms of Nixon’s FAP were one of the major vehicles through which the NWRO asserted their analytic interventions and developed their antiwork politics.

The same year Nixon proposed FAP, the NWRO submitted to congress The Adequate Income Bill, seizing the momentum of FAP but challenging many of its shortcomings. Pamphlets comparing the two proposals underscored that the NWROs goals were simple: “$5500 for a family of four; No forced work; Covers everyone; Cost of living increases; Guarantees justice and dignity.

The Adequate Income Bill contains some of the most formal, cohesive articulation of NWRO’s antiwork analysis. The bill’s introduction contends,

Millions of Americans are not on welfare but are unable to secure an adequate income from the wages they earn. The real employment problem is not that people need jobs and jobs need people. It is that employment does not distribute wealth the way its advocates claim it does. As a wealth distribution system employment has never worked well for the poor, especially the black poor. Even if all eligible Americans were employed today, the poverty rate would not be seriously affected

Once again, the NWRO firmly staked their position that waged labor is fundamentally incapable of distributing wealth and that even if full employment was achieved, poverty would not be significantly ameliorated. Additionally, despite frequent claims that NWRO held strongly gendered notions about who should work and who should stay at home, the bill is framed in universal, gender neutral language (like much of the movement’s content), insisting only that families have enough income to sustain themselves The bill was not only the culmination of the NWRO’s efforts to block passage of Nixon’s FAP, but also of years of developing consciousness and refining demands through which their antiwork politics were concretized

Nevertheless, activists in the movement understood the bill as “only a symbol of the work that lies ahead. Securing the material means to survive without the compulsion of employment was one key aspect of their battle, but it was far from their only fight.

Refusing the Moral Ideology of Work

In addition to attempting to secure guaranteed income, which would enable people to decouple their survival from wage work, participants in the welfare rights movement fought against the ideological hegemony of work. Challenging work’s ideological power is central to antiwork politics in that advocates seek to not only “confront its reification and depoliticization but also its normativity and moralization. This is an especially fundamental component of resisting work’s hegemony because, as Weeks insists, “[w]ork is not just defended on grounds of economic necessity and social duty; it is widely understood as an individual moral practice and collective ethical obligation. Activists in the NWRO recognized the incredible power of the work ethic, especially its function to delineate who is considered deserving of respect and well being and they sought to challenge this whenever possible.

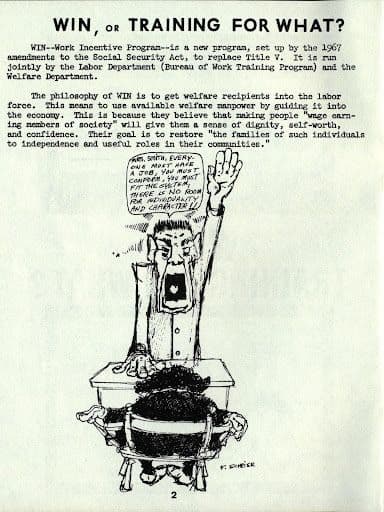

Activists in the movement took particular umbrage at the belief that “work is the source of all good, their frustrations with the incorrect persistence of this hegemonic narrative were articulated throughout many publications. For example, a widely reproduced NWRO pamphlet from May 1969 (See Figure 1) criticized the overvaluation of waged labor implicit in a workfare provision: “they believe that making people ‘wage earning members of society’ will give them a sense of dignity, self-worth, and confidence. Their goal is to restore ‘the families of such individuals to independence and useful roles in their communities’. Lest it not be explicit enough that NWRO perceived this intention with scorn, irony and disapproval, below this text appeared a cartoon figure of a towering, uniformed man giving a Nazi salute and screaming at a tiny, cowering woman seated in front of him. The word bubble above his military-style haircut reads, “Mrs. Smith everyone must have a job, you must conform, you must fit the system, there is no room for individuality and character!!”

Figure 1. WIN or training for what?

Representing waged labor with an unhinged, fascist, man in military garb would have been especially resonant to an explicitly antiwar organization such as the NWRO Additionally, the notion that forcing welfare recipients to work would restore dignity and a “useful role” to women who believed themselves to be engaged in extremely useful roles in their communities—not just at home—would have been absurd to the pamphlet’s intended audience.

Welfare activists rarely missed an opportunity to insist that society’s reverence for wage work was misplaced. One pamphlet, criticizing a workfare program complained, “[i]t forces people to work and doesn’t give them any choice in the matter. It is based on the prejudiced attitude that welfare people are no good. They assume that only people with jobs are useful, good citizens, so the only way welfare people can become useful is to make them have jobs. Although many of these statements appear in the context of criticizing the implementation and efficacy of “terrible and very inadequate” training programs, welfare activists did not seek to improve these programs. Rather, they identified a major adversarial target in the “philosophy” and “attitude” which ascribes a moral value to waged labor and wrongfully assumed that those without employment also lack “dignity” “selfworth” and “confidence.” Note that in these publications welfare activists do not argue for the valor or the productive relevance of reproductive labor in contrast to waged labor, rather they develop an expansive and open-ended criticism of wage work and its valorization

Despite being a majority female organization, which occasionally relied on gendered slogans such as “mother power,” the crux of the NWRO’s analysis and rigorous theoretical interventions into wage work, particularly as it appears in policy proposals and other organizational publications, was fundamentally universal with regards to gender. On the other hand, while articulating a multi-racial political project their analysis demonstrates careful attention to the racialized nature of labor in American society, or what Kelley identifies as a “racialized class consciousness. In the following section I examine how this racialized class consciousness shaped the NWRO’s desire for income decoupled from work.

“We’ve Worked Enough”

Black feminists have long underscored the generative relationship between lived experiences and political analysis, or as the Combahee River Collective emphasized, “the political realization that comes from the seemingly personal experiences of individual black women’s lives. Members of the NWRO drew from their lived experiences to develop their antiwork politics, and activists often referred to their personal experiences as evidence substantiating their claims that employment was inadequate and fundamentally incapable of meeting their material needs. As approximately 90% of the NWRO membership was Black activists frequently situated their criticisms of wage labor in the racialized history of U.S. labor. In addition to arguing that labor did not resolve the issue of poverty, especially for Black people, they argued that welfare recipients, and poor Black people in particular deserved a guaranteed income because they had already worked enough This argument has a dual temporality—both as individuals, many of whom had been working since they were children in racialized industries such as sharecropping or domestic work they felt they had worked enough for a lifetime, but also as a race, across generations who had produced untold wealth, little of which had accrued to them.

In the spring of 1968, the NWRO’s newspaper, The Welfare Fighter, reported testimonies from the large crowd attending a Mother’s Day march, including that of Mrs. Perlie Mae Bynclum of Lamast, Mississippi who, the newspaper noted, “told it like it is.” Bynclum exclaimed, ‘I picked cotton, I hauled wood, I done everything—and I got nothing to show for it’ The Jan–Feb 1972 issue of the Welfare Fighter contained a statement by Curtis L. Butler who argued for situating the welfare debates within the racialized history of American labor. Butler pointed out that mainstream welfare debates occluded an essential component of the issue: that individuals like himself were impoverished and had to rely on welfare because throughout American history Black families had been subjected to generations of forced labor and stolen wages:

And you say you want to take them off welfare. How can you take them off the welfare? I shouldn’t be on welfare. You know why? Because my great great grandfather worked for nothing. My great grandfather worked for nothing, my grandfather worked for nothing. My daddy worked for nothing and they worked hell out of me for nothing. I ain’t got nothing for me to live for but this boy now. But you see if I would have gotten paid for the minimum wages and got bread and justice any white man or anybody else would, I would not be on the welfare

An explicit reference to the unpaid and underpaid labor performed by African Americans, as articulated above, helped underpin both a rejection of work as the solution to poverty, as well as a sense of rightful entitlement to government benefits. Recall the unequivocal statement that reappeared throughout movement publications: “employment does not distribute wealth the way its advocates claim it doe for many members of the welfare rights movement, the failure of labor to procure many of the promised benefits to the laborer was especially obvious given the extent of Black dispossession in American history.

Appeals to the racialized history of American labor were also used to argue for the direct redistribution of wealth. A number of the songs in the welfare songbook, many of which were altered church songs and Civil Rights staples, reflected this analysis. For example, the lyrics to “Right to Live” by Frederick D. Kirkpatrick encapsulate much of the movement’s ideological perspective, despite its unlikely occlusion of Black women’s labor.

Ev’rybody’s got a right to live, Ev’rybody’s got a right to live— And before this campaign fails, We’ll all go down in jail

Ev’rybody’s got a right to live.

On my way to Washington feelin’ awful sad Thinkin’ ‘bout an income

That I never had.

Black man dug the pipeline Hewed down the pines Gave his troubles to jesus

Kept on toeing the line. (Chorus)

Black man dug the ditches Both night and day

Black man did the work

While the white man got the pay.

I want my share of silver I want my share of gold

I want my share of justice

To save my dying soul.

“A Right to Live” was a persistent rallying cry of the movement, and later, a campaign mounted by the lawyers affiliated with the NWRO It is worth emphasizing that in Kirkpatrick’s song this right to the income “never had” was articulated as rooted in the historic injustices of American slavery and racialized labor that long denied Black Americans’ income. They were now therefore owed an income (“silver, gold, justice”) decoupled from labor.

As scholars of the Civil Rights Movement have often reflected, and Kirkpatrick noted explicitly in the liner notes of the album on which “Right to Live” was featured, “[m]usic is the easiest way to tell the story of what we’re trying to do; [our] songs are one of the best tools for getting people together Songs can convey a movement’s boldest visions—such as the epigraph which opens this article, insisting on a world with no workers, only joy.

By the mid 1960s many radical Black organizations and publications such as the 1969 Black Manifesto advanced by James Foreman’s Black National Economic Conference, and other currents of the radicalizing Civil Rights Movement, held similar positions as those articulated by the NWRO on reparation The NWRO and Foreman were particularly close allies, and Foreman pledged to redistribute 10 million dollars of the reparations he demanded from churches directly to the NWRO

Reinforcing the claim of historical continuity between the brutal exploitation of chattel slavery and their own work experiences, literature produced by the WRM often called work requirements “slave jobs.” This argument reappears throughout much of the welfare rights literature and is a frequent visual presence in protest materials. Posters and pamphlets opposing FAP, for example, often contained an image of an African American woman scrubbing a floor or performing some other type of arduous, unpleasant labor, with what appears to be a whip hovering above her (see the Figure 2). On one of NWRO’s posters, bold red text exclaimed: “NIXON-MILLS WELFARE PLAN: SLAVE JOBS.” The mugshot of Wilbur D. Mills, a congressman central to the FAP bill was featured on another NWRO poster, with the tagline “WANTED FOR CONSPIRACY TO STARVE CHILDREN, DESTROY FAMILIES, FORCE WOMEN IN TO SLAVERY AND EXPLOIT POOR PEOPLE. Again and again, NWRO made forced work requirements central to their rejection of welfare reforms and likened their imposition to slavery. In another pamphlet renouncing FAP, NWRO activists rejected what they described as its compulsion to “WORK or STARVE In the pamphlet “Steps Toward True Welfare Reform” NWRO envisioned a future welfare policy that prohibited any “forced work.

Figure 2. Slave jobs.

NWRO’s renunciation of “forced,” “compulsory” and “slave” labor was certainly rooted in and meant to recall the brutal racial legacy of chattel slavery, but it also echoed long standing criticisms of wage labor as a system of “wage slavery.” A major theme in antiwork and anti-capitalist analyses is emphasizing the unfreedom of a system in which people have no other means of securing their needs than to work for someone else, and the extent to which force, domination, and compulsion are intractable components of the work regime Advocates of guaranteed income underscore that one of the policy’s particularly compelling features is its potential for undermining the “work or starve” compulsion that defines wage work. For example, sociologist and UBI advocate Erik Olin Wright has described the structural shift which might take place through a generous guaranteed income program as particularly appealing because for the first time, “the labor contract becomes more nearly voluntary since everyone has the option of exit. For similar reasons, Kathi Weeks has described basic income as “an invocation of the possibility of freedom. Daniel Patrick Moynihan, one of the architects of the much abhorred FAP, also noted this relationship to compulsion and freedom contained in guaranteed income programs. Moynihan, surprised that his proposal received so little support from the Left, boasted that “A Yugoslav Marxist, for one, was reported as commenting within his circles that were [FAP] to pass it might well be the most important social legislation in history in that it would finally free the individual and his family from the myriad and inescapable forms of coercion which society exerts through the employment nexus. Welfare recipients were undoubtedly more familiar with the particular intricacies of FAP’s proposed guaranteed income than this unnamed Marxist, and therefore less optimistic that it would achieve this objective, which they too sought.

The Difficulty of Critiquing and Refusing Work

Above I have examined especially pronounced examples of what I identify as the antiwork politics animating the welfare rights movement, as they appear primarily in the movements’ archives. In particular, I have highlighted the way activist-theorists attempt to unsettle the logic of the work ethic, which insists “only people with jobs are useful, good citizens. Additionally, participants in the WRM challenged the reverence of work especially by underscoring the inability of wage work to resolve the problem of poverty, and they situated their demand for guaranteed income in the legacy of unpaid labor performed by African Americans, while at the same time emphasizing a universal “right to live” which was impeded by the labor market’s compulsion to work or starve. Through these generative interventions, activists associated with the movement reveal themselves to be inventive social theorists whose thoughts and action aligns with the often underappreciated tradition of antiwork politics.

In highlighting these features of the movement, I have focused on what Kristin Ross identifies in her work on the 1960s as “what it is that has been lost.” Ross emphasizes, as I do here, “a special effort to locate memories that do not conform to the predispositions of the present, that do not serve to legitimate contemporary configurations of power. In other words, I have given particular attention to amplifying what Saidiya Hartman describes as “moments of withholding, escape and possibility, moments when the vision and dreams of the wayward seemed possible. In a sense, both Ross and Hartman articulate a similar methodological approach, urging scholars to highlight and home in on moments of bold, counter hegemonic expansions of imagination and possibility when they appear. Kelley explains that emphasis on these moments is so crucial, in part because of the constant counter pressures that impede these radical ideas from ever gaining traction at all. Kelley notes, “[r]ecovering the poetry of social movements, however, particularly the poetry that dreams of a new world, is not such an easy task … It is a testament to the legacies of oppression that opposition is so frequently contained, or that efforts to find “free spaces” for articulating or even realizing our dreams are so rare or marginalized. In other words, before these ideas gain enough traction to make it into any kind of collective movement, let alone the archive, they are often stamped out. Hartman, Kelley and Ross’s work similarly underscore the remarkable tenacity required to not only develop, but articulate trenchant counter hegemonic critiques such as the antiwork freedom dreams generated by the welfare rights movement The next section provides further empirical support for Ross and Hartman’s insistence that uncovering these types of ideas requires particular effort.

Strategic Concealment

To be sure, within the historical archive of the WRM there are also articulations that contradict the radical counter hegemonic tendencies I have examined throughout this paper. The scholar and activist Frances Fox Piven, who worked closely with the WRM, recalls an incident when the NWRO staff advertised a “training” session to which dozens of recipients showed up, and quickly left, disappointed, upon realizing they were not attending a job training program as they hoped, but rather a training for political organizing Other times, despite many examples of the movement’s careful efforts to undermine the logic of the work ethic, the NWRO also occasionally resorted to arguments that upheld this ethic as an arbiter of decency and deservingness. For example, a factsheet addressing frequently asked questions about the NWRO’s counter proposal to FAP, anticipated the question: “Wouldn’t people stop working if they were guaranteed an income?” “no,” the pamphlet asserts “poor people want to work and have to work harder than others. Poor people respond to the same incentives as everyone else. How can scholars reconcile the apparent contradiction in which, despite devoting an enormous amount of effort to challenging the notion of deservingness delineated by wage work, the movement nonetheless occasionally attempted to reassure skeptics by resorting to the same loathed logic? In 1969 longtime NWRO organizer Hulbert James offered insight into this putative contradiction while discussing the strategy animating NWRO’s public image:

Two persons asked me about ideology and whether what we are doing is relevant in terms of the whole revolutionary crowd … One of the things we are sharp about is in not advertising what we are doing. I think that one of the problems that the Panthers are in trouble today is not so much that they are a vanguard force, but that they have come out with a clear call to the people for power and revolution. We are doing the same thing but we are not coming out with a manifesto saying where we are going. We know where we are going and the ladies know where they are going. To advertise that is only to bring an onslaught we are not ready to deal with

Here, James explicitly states that ideological subterfuge, or strategic concealment of the movement’s beliefs and aspirations was a necessary and clever tactic, deployed intentionally in hopes of the NWRO surviving and avoiding the kind of intense repression faced by contemporaries such as the Black Panther Party. Keen to emphasize the similarities between the NWRO and “the whole revolutionary crowd,” James underscores that the major distinction was the vocalization of these shared beliefs: “we are doing the same thing but we are not coming out with a manifesto saying where we are going.” To say that the Panthers were “in trouble” in 1969 would have been euphemistic at best Although it may not have been as unequivocally clear as it is today that the federal government was waging war on them, it was obvious to the NWRO that when organizations like the Panthers or the Young Lords boldly and clearly articulate their political positions, they were met with violent and often deadly repression Therefore, the NWRO learned to mute and downplay messages that might “bring an onslaught.”

Social movements are notoriously sites of conflict over guiding ideologies, strategy, tactics and more and there are certainly participants who disagreed with James’ assessment that the WRM was “doing the same thing” as the Panthers Nevertheless, James’ reflection on intentionally concealing certain ideas helps explain that the occasional appearance of compliance with the ideology of work and other hegemonic norms may have been strategic and did not encapsulate the genuine, expansive analyses and demands of the movement as a whole, which may have been frequently muted.

The WRM’s strategy of downplaying the revolutionary aspects of their politics also underscores Ross and Hartman’s emphasis on amplifying counter hegemonic ideas which are frequently, as James confirms, silenced or quieted as a survival mechanism. The seeming ambiguities in the movement’s record underscore the difficulties entailed in developing antiwork politics, and more generally, any political project that seeks to challenge widely accepted, hegemonic institutions for which there exist few ready alternatives. Both because, as the Panthers example demonstrates, promoting certain ideas can be extremely dangerous, and in capitalist societies there are few means of surviving outside wage work for those not independently wealthy

Why Does It Matter?

Emphasizing the antiwork politics of the welfare rights movement is important for a number of reasons, three of which I elucidate here: First, and most obviously, is the pursuit of historical accuracy. Scholars should attempt to accurately reflect the interests and objectives of the subjects they study. There is a particular importance in listening, and accurately representing the self-determination of people whose contributions, understandings and ideas are not often taken seriously. Throughout the history of the United States, it is well documented that women, poor people, and people of color have been prevented from contributing to and shaping political discourse and policy, especially on issues relevant to their lives In other words, whatever the activists involved with the welfare rights movement said and did, scholars should try to reflect and document it as accurately as possible. The obfuscation of many key articulations from the WRM’s historical record, presented above, has rendered this difficult. Additionally, recognizing the manifold challenges people face in asserting bold, visionary political alternatives, especially those that call into question venerated institutions, encourages scholarship to give past visionaries’ brave articulations particularly close consideration.

Secondly, the WRM’s freedom dream of a world with “no workers” is relevant to contemporary debates about guaranteed income One of the major criticisms frequently parried at antiwork politics is that they are a privileged theoretical thought experiment with little connection to the actual lived experiences and desires of the working class. This mischaracterization has stood, in large part, because of a dearth of empirical studies on antiwork politics and the pursuit of guaranteed income by working class people and social movements. This study contributes to expanding this small body of literature by providing richly descriptive analysis by affected populations, as well as by challenging the perception that antiwork politics are solely of interest to leftist European theorists. I have demonstrated the way poor Black women activists formulated an antiwork freedom dream, drawing from their own experiences, and the history of Black labor in the United States.

Finally, exhuming the legacy of the welfare rights movement and forthrightly adding “antiwork” politics as a central element of the movement’s freedom dream, provides us with a more abundant repertory of innovative, expansive ideas—and their praxis—we may draw from to confront the dire challenges facing contemporary society. This moment, perhaps more so than any during the past half century, appears ripe for a serious reckoning with the work regime.

Although every era in American history is, in its own way, a brutal demonstration of the work regime, the Covid-19 pandemic has revealed its contradictions and cruelty in a particularly stark light. The pandemic upended nearly every facet of life, and yet people were obligated to continue working as though nothing had changed. Even relatively privileged office workers who were able to work safely at home, faced enormous challenges navigating childcare, health crises, and more, often working even longer hours than before the pandemic. The mental health consequences for these workers have been dire Low wage “essential” workers who lacked the ability to work from home were forced to make the devastating decision of whether to face eviction, starvation, or catching a potentially deadly or severely debilitating disease, in order to keep meat processing plants, restaurants, and Amazon fulfilment centers running as usual. The exact number of deaths that resulted from forcing people to continue showing up to already otherwise dangerous and poorly remunerated jobs in the midst of a respiratory pandemic—without vaccines or proper protective protocols—is hard to ascertain exactly, in large part because of obfuscatory systems of oversight It is however, unsurprising that poor people of color have experienced especially disproportionate mortality throughout the pandemic, in part as a result of being forced to work low wage jobs, in person. Perhaps no one more succinctly articulated the usually unspoken logic of the work regime than Texas’s Lieutenant Governor, who just a few short weeks into the pandemic argued for reopening businesses across the state, stating bluntly, “[t]here are more important things than living.

A year and a half into the Covid-19 pandemic workers have begun refusing the dangers and frustrations of work en masse in a surge of work refusal many are calling “The Great Resignation.” Three separate months of 2021 saw the highest numbers of “quits” since the Bureau of Labor Statistics started keeping records. The Reddit thread “/antiwork” which features the slogan “Unemployment for all, not just the rich!” became one of the fastest growing areas of the popular website. By November 2021, the group boasted over a million members who posted anti work memes and cheered gleefully as others recounted in florid detail telling their bosses to stuff it On the other side of the globe, “tangping” or the “lay down flat” movement emerged in China, imploring people to resist the cult of overwork by refusing to engage all together. In a few short weeks of the autumn of 2021, antiwork politics went from fringe political concept, to a theme frequently discussed in the New York Times

Social scientists will undoubtedly debate for years the extent to which variables like flush saving accounts, burn out, impending climate doom, lack of childcare, or a new critical perspective on work, fueled these remarkable trends. For now, to the extent that these developments can be understood as instances of antiwork politics at all, they remain largely nascent, atomized, and far from the bold, collective project of welfare rights activists. And yet, they also provide a glimmer of hope for a possible future full of raucous antiwork mobilization.

To navigate our way out of the manifold crises society faces, we need to consider all of the boldest ideas we can muster, especially those that encourage a capacious sense of possibility, ideas that reject defensiveness and refuse to be curtailed by manufactured scarcity Returning to the antiwork freedom dreams of the welfare rights movement encourages us to stretch our brittle radical imaginations, and provides us with fodder for conceiving of different pleasures and new worlds, ideally ones with much less work and more joy for all

1National Welfare Rights Organization songbook, Guida West Papers, Sophia Smith Collection, Box 27, Folder 13. Smith College.

2George F. E. Rud'e, Ideology & Popular Protest (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995); Antonio Gramsci, Selections from the Prison Notebooks, ed. Quintin Hoare and Geoffrey Nowell Smith, 1989 ed. (New York: International Publishers Co, 1971); Rick Fantasia, Cultures of Solidarity: Consciousness, Action, and Contemporary American Workers (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988); Frances Fox Piven and Richard Cloward, Poor People’s Movements: Why They Succeed, How They Fail (New York: Vintage, 1978); Robin D. G. Kelley, Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination, New ed. (Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 2003); Kristin Ross, May ’68 and Its Afterlives, 1st ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002); Erik Olin Wright, Envisioning Real Utopias (London: Verso, 2010).

3Special thanks to Michelle O’Brian who read innumerable drafts of this project and pointed out that what I was really describing in the WRM was a “freedom dream.”

4Kelley, Freedom Dreams, 8.

5Brittney C. Cooper, Beyond Respectability: The Intellectual Thought of Race Women (Urbana, IL: Chicago Springfield University of Illinois Press, 2017); Saidiya Hartman, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval, Reprint ed. (New York: WW Norton, 2020).

6Edward P. Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class, Vintage ed. (New York: Vintage Books, 1966), 13.

7This claim can be supported by examining the challenges millions of working people in the U.S. face paying for basics such as rent, food, childcare, or covering an unexpected emergency. David Cooper, Zane Mokhiber, and Ben Zipperer, “Raising the Federal Minimum Wage to $15 by 2025 Would Lift the Pay of 32 Million Workers: A Demographic Breakdown of Affected Workers and the Impact on Poverty, Wages, and Inequality,” Economic Policy Institute (blog), March 9, 2021, https://www.epi.org/ publication/raising-the-federal-minimum-wage-to-15-by-2025-would-lift-the-pay-of-32-millionworkers/ (accessed December 13, 2021). Jeanna Smialek, “Many Adults Would Struggle to Find $400, the Fed Finds.” The New York Times, May 23, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/ 2019/05/23/business/economy/fed-400-dollar-survey.html; Alicia Adamczyk, “Full-Time Minimum Wage Workers Can’t Afford Rent Anywhere in the US, According to a New Report,” CNBC, July 14, 2021, https://www.cnbc.com/2021/07/14/full-time-minimumwage-workers-cant-afford-rent-anywhere-in-the-us.html.

8Piven and Cloward, Poor People’s Movements; Guida West, The National Welfare Rights Movement: The Social Protest of Poor Women (New York: Praeger, 1981); Martha F. Davis, Brutal Need: Lawyers and the Welfare Rights Movement, 1960–1973, New ed. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1995); Jacqueline Pope, Biting the Hand That Feeds Them: Organizing Women on Welfare at the Grass Roots Level (New York: Praeger, 1989).

9Nick Kotz, A Passion for Equality: George A. Wiley and the Movement, 1st ed. (New York: Norton, 1977); Annelise Orleck, Storming Caesars Palace: How Black Mothers Fought Their Own War on Poverty, Annotated ed. (Boston: Beacon Press, 2006); Felicia Ann Kornbluh, The Battle for Welfare Rights: Politics and Poverty in Modern America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007); Lawrence Neil Bailis, Bread or Justice: Grassroots Organizing in the Welfare Rights Movement (Lexington, MA: Lexington Books, 1974).

10Premilla Nadasen, Welfare Warriors: The Welfare Rights Movement in the United States (New York: Routledge, 2004); West, The National Welfare Rights Movement.

11Edward V. Sparer, “The Right to Welfare,” in The Rights of Americans: What They Are–What They Should Be, eds. Norman Dorsen and American Civil Liberties Union, 1st ed. (New York: Pantheon Books, 1971). Davis, Brutal Need; Elizabeth Bussiere, (Dis)Entitling the Poor: The Warren Court, Welfare Rights, and the American Political Tradition, New ed. (University Park, PA: Penn State University Press, 2001).

12Anne M. Valk, “‘Mother Power’: The Movement for Welfare Rights in Washington, D.C., 1966–1972,” Journal of Women’s History 11, no. 4 (2000): 34–58, doi:10.1353/jowh.2000. 0014; Premilla Nadasen, “Expanding the Boundaries of the Women’s Movement: Black Feminism and the Struggle for Welfare Rights,” Feminist Studies 28, no. 2 (2002): 271–301, doi:10.2307/3178742; Ellen Reese and Garnett Newcombe, “Income Rights, Mothers’ Rights, or Workers’ Rights? Collective Action Frames, Organizational Ideologies, and the American Welfare Rights Movement,” Social Problems 50, no. 2 (2003): 294–318, doi:10.1525/sp.2003.50.2.294; Georgina Denton, “‘Neither Guns nor Bombs – Neither the State nor God – Will Stop Us from Fighting for Our Children’: Motherhood and Protest in 1960s and 1970s America,” The Sixties 5, no. 2 (2012): 205–28, doi:10.1080/17541328. 2012.712012; Mary E. Triece, “Credible Workers and Deserving Mothers: Crafting the ‘Mother Tongue’ in Welfare Rights Activism, 1967–1972,” Communication Studies 63, no. 1 (2012): 1–17; Holloway Sparks, “When Dissident Citizens Are Militant Mamas: Intersectional Gender and Agonistic Struggle in Welfare Rights Activism,” Politics & Gender 12, no. 4 (2016): 623–47, doi:10.1017/S1743923X16000143. For an initial critique of these claims see Wilson Sherwin and Frances Fox Piven, “The Radical Feminist Legacy of the National Welfare Rights Organization,” WSQ: Women’s Studies Quarterly 47, no. 3–4 (2019): 135–53, doi:10.1353/wsq.2019.0060.

13Felicia Kornbluh, “The Goals of the National Welfare Rights Movement: Why We Need Them Thirty Years Later,” Feminist Studies 24, no. 1 (1998): 65–78, doi:10.2307/3178619.

14Kornbluh, “The Goals of the National Welfare Rights Movement,” 67.

15Melinda Cooper, Family Values: Between Neoliberalism and the New Social Conservatism (New York: Zone Books, 2017).

16I rely on the terminology “working class,” despite its contradiction in this context, with the recognition that the working class has always included people who are outside of employment. Robin D. G. Kelley, Race Rebels: Culture, Politics, and the Black Working Class (New York: Free Press, 1996).

17Edward Granter, Critical Social Theory and the End of Work (Farnham, England: Ashgate, 2009); Kathi Weeks, The Problem with Work: Feminism, Marxism, Antiwork Politics, and Postwork Imaginaries (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011); David Frayne, The Refusal of Work: The Theory and Practice of Resistance to Work (London: Zed Books, 2015); David Graeber, Bullshit Jobs (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2018); Alastair Hemmens, The Critique of Work in Modern French Thought: From Charles Fourier to Guy Debord, 1st ed. (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019).

18Roland Simon, Fondements critiques d’une th'eorie de la r'evolution: au-del'a de l’affirmation du prol'etariat (Paris: Senonevero, 2001), 252. Translation author’s own.

19Even Paul Lafargue, in his famously scathing criticism of the work ethic under capitalism and a key text in the antiwork tradition, proposes three-hour work days as his remedy, rather than eschewing any effortful activity entirely. Paul Lafargue, The Right to Be Lazy, and Other Studies (London: Forgotten Books, 2012).

20Ideologically this shares a great deal with, and contemporary antiwork advocates have much to learn from, disability rights activists who have for far too long been arguing in siloed isolation against the morality of a productivist society, especially when 1 in 4 adults in the U.S. have a disability, “Disability Impacts All of Us,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/infographic-disabilityimpacts-all.html. Branka Magas Coulson and Hilary Wainwright, “The Housewife and Her Labour under Capitalism—A Critique,” New Left Review no. 89 (1975): 51–71; Lourdes Beneria, “Conceptualizing the Labor Force: The Underestimation of Women’s Economic Activities,” Journal of Development Studies 17, no. 3 (1981): 10–28.

21Philippe Van Parijs, Arguing for Basic Income: Ethical Foundations for a Radical Reform (London: Verso, 1992); Philippe Van Parijs, “Basic Income: A Simple and Powerful Idea for the Twenty-First Century,” Politics & Society 32, no. 1 (2004): 7–39, doi:10.1177/ 0032329203261095; Bruce Ackerman, Anne Alstott, and Philippe van Parijs, Redesigning Distribution: Basic Income and Stakeholder Grants as Cornerstones for an Egalitarian Capitalism (London: Verso, 2006).

22See for example, Mariame Kaba, We Do This ’Til We Free Us: Abolitionist Organizing and Transforming Justice (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2021); Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Change Everything: Racial Capitalism and the Case for Abolition (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2022).

23Simon, Fondements critiques d’une th'eorie de la r'evolution, 252.

24Weeks, The Problem with Work, 124.

25Kristin Ross, The Emergence of Social Space: Rimbaud and the Paris Commune (London: Verso, 2008).

26Graeber, Bullshit Jobs; Tamara Keith, “Just How Many Jobs Would The Keystone Pipeline Create?” NPR, December 14, 2011, https://www.npr.org/sections/itsallpolitics/2011/12/14/143719155/just-how-many-jobs-would-the-keystone-pipeline-create.

27A few rare exceptions to this include: Jacques Ranci'ere, Proletarian Nights: The Workers’ Dream in Nineteenth-Century France (London: Verso Books, 2012) which examines instances of resistance to work articulated throughout French working class cultural artifacts in the mid 19th century. Michael Seidman, Workers against Work: Labor in Paris and Barcelona during the Popular Fronts (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991) argues for viewing incidents of sabotage and shirking by radicals in France and Spain in the 1930s as “guerilla warfare against work,” a claim Jamie Woodcock, Working the Phones: Control and Resistance in Call Centers (Pluto Press, 2016) updates on a much smaller scale to present day UK. Kathi Weeks’s The Problem with Work identifies the Wages for Housework movement, as well as the Welfare Rights Movement, as examples of an antiwork movement. Italy’s Autonomia has also been (sparsely) written about through this lens: Patrick Cuninghame, “Autonomia in the 1970s: The Refusal of Work, the Party and Power,” Cultural Studies Review 11, no. 2 (2005): 77–94.

28Robin D. G. Kelley, Race Rebels: Culture, Politics, and the Black Working Class (New York: Free Press, 1996), 17.

29Hartman, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments, xiv. A number of scholars emphasize that a major impediment to social movement scholarship is scholars’ entrenched, preconceived notions of what counts as resistance and who might be undertaking it. Aldon Morris, “Social Movement Theory: Lessons from the Sociology of WEB Du Bois.” Mobilization: An International Quarterly 24, no. 2 (2019): 125–36. Frances Fox Piven and Richard Cloward, Poor People’s Movements. Also Kelley, Race Rebels. This problem is especially compounded by the reach of traditional work values. (See Weeks, The Problem with Work, 247.)

30Jean Comaroff and John Comaroff, “After Labor,” Critical Historical Studies 7, no. 1 (2020): 87, doi:10.1086/708007.

31Simon, Fondements critiques d’une th'eorie de la r'evolution.

32David Calnitsky, Jonathan P. Latner, and Evelyn L. Forget, “Life after Work: The Impact of Basic Income on Nonemployment Activities,” Social Science History 43, no. 4 (2019): 657–77, doi:10.1017/ssh.2019.35; Ingrid Robeyns, “Introduction: Revisiting the Feminism and Basic Income Debate,” Basic Income Studies 3, no. 3 (2008), doi:10.2202/1932-0183.1137; Sherwin and Piven, “The Radical Feminist Legacy of the National Welfare Rights Organization.”

33A very partial list of texts that explore and expand the black radical tradition include Cedric J. Robinson, Black Marxism, Revised and Updated Third Edition: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2021); David Scott, “On the Very Idea of a Black Radical Tradition,” Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism 17, no. 1 (2013): 1–6; Chandan Reddy, “Neoliberalism Then and Now,” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 25, no. 1 (2019): 150–55, doi:10.1215/ 10642684-7275362; Gaye Theresa Johnson and Alex Lubin, eds., Futures of Black Radicalism (London: Verso, 2017). Hartman, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments; Kelley, Freedom Dreams; Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study (Wivenhoe, UK: Minor Compositions, 2013).

34Mathew Forstater, “From Civil Rights to Economic Security: Bayard Rustin and the African-American Struggle for Full Employment, 1945–1978,” International Journal of Political Economy 36, no. 3 (2007): 63–74.

35Ross, May ’68 and Its Afterlives; Joshua Bloom and Martin, Black against Empire: The History and Politics of the Black Panther Party, 1st ed. (Oakland: University of California Press, 2016).

36Michael Watts, “1968 and All That … ,” Progress in Human Geography 25, no. 2 (2001): 161, doi:10.1191/030913201678580467.

37Ross, May ’68 and Its Afterlives; Bloom and Martin, Black against Empire; Watts, “1968 and All That …” share this analysis.

38Archives themselves are far from perfect records of the past, as they themselves are sites of exclusion and silence Saidiya Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts,” Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism 12, no. 2 (2008): 1–14, doi:10.1215/-12-2-1; Ann Laura Stoler, Along the Archival Grain: Epistemic Anxieties and Colonial Common Sense (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2009); Clare Hemmings, Considering Emma Goldman (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017).

39Betty Friedan, The Feminine Mystique (New York: Norton, 2001).

40The National Advisory Commission on Civil, Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, 8th Printing ed. (New York: Pantheon Books, 1968).

41Paul Le Blanc and Michael D. Yates, A Freedom Budget for All Americans: Recapturing the Promise of the Civil Rights Movement in the Struggle for Economic Justice Today (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2013); David P. Stein, “‘This Nation Has Never Honestly Dealt with the Question of a Peacetime Economy’: Coretta Scott King and the Struggle for a Nonviolent Economy in the 1970s,” Souls 18, no. 1 (2016): 80–105, doi:10.1080/ 10999949.2016.1162570.

42A. Philip Randolph Institute, A ‘Freedom Budget’ for All Americans: Budgeting Our Resources, 1966–1975, to Achieve Freedom from Want (New York: A. Philip Randolph Institute, 1966), 10.

43Blanc and Yates, A Freedom Budget for All Americans.

44“Goals of the National Welfare Rights Organization,” NWRO Papers, Box 2083, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University.

45I argue in the manuscript length version of this article (Wilson Sherwin, “Rich in Needs: The Forgotten Radical Politics of the Welfare Rights Movement” (PhD diss., CUNY Graduate Center, 2019)) that one of the major problems with existing literature on the movement is that scholars focus on statements made at the very beginning of the movement, ignoring the progressive development towards a sharper, more radical analysis which emerges as the movement gained members and influence. Additionally, existing scholarship rarely considers the target audience for particular articulations, overemphasizing statements made for journalists, or politicians as the true perceptions of members, rather than considering strategic motivations for highlighting certain issues in particular situations. Here I focus on statements made during the height of the movement’s power and radicalism, and primarily but not exclusively intended for internal movement audiences.

46William Whitaker, “The Determinants of Social Movement Success: A Study of the National Welfare Rights Organization” (PhD Thesis, Brandeis University, 1970), 243, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/36108099_The_determinants_of_social_ movement_success_a_study_of_the_National_Welfare_Rights_Organization.

47West Papers Box 27, Folder 14.

48Karl Marx, made similar arguments about poverty being constitutive of the working class experience. Marx argues that despite the enormous value produced by laborers, the result of capitalist accumulation for the working class is “pauperism.” For Marx, “pauperism forms a condition of capitalist production, and of the capitalist development of wealth. It forms part of the faux frais of capitalist production.” Karl Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy (London: Penguin, 1992), 797. in other words, for Marx, as well as the NWRO, poverty is an inevitable biproduct of capitalism.

49“The NWRO Adequate Income Program $7500 NOW!” NWRO Papers, Box 2083, Folder “NWRO Publications.”

50I am not suggesting that members of the NWRO were secretly Marxist, rather than their analysis of waged labor echoes key elements of Marxian analysis. This may suggest that Marx’s analysis so aptly encapsulates the working class’ experience of work that across different continents and centuries, people of different races and genders come to similar observations about the nature of work under capitalism. The conceptual parallels also indicated that the fundamental radicalism of the NWRO has been vastly underestimated or overlooked by scholars in the intervening years.

51NWRO Papers, Box 2083, Folder “NWRO Publications.”

52Simon, Fondements critiques d’une theorie de la revolution. This logic will be familiar to readers from the work of carceral state abolitionists such as Angela Y. Davis, Are Prisons Obsolete? (Seven Stories Press, 2011); Eric A. Stanley and Nat Smith, eds., Captive Genders: Trans Embodiment and the Prison Industrial Complex (Oakland, CA: AK Press, 2011); William Widmer/Redux, “The Case for Abolition,” The Marshall Project, June 19, 2019, https://www.themarshallproject.org/2019/06/19/the-case-for-abolition; https:// abolitionjournal.org/.

53Kornbluh identifies guaranteed income programs as “a kind of anti-New Deal and antiWar on Poverty, a response to the problems of male under-employment, persistent poverty, and black rage that differed from anything the United States had yet tried.” Felicia Kornbluh, “Is Work the Only Thing That Pays-The Guaranteed Income and Other Alternative Anti-Poverty Policies in Historical Perspective,” Northwestern Journal of Law & Social Policy 4 (2009): 61. A similar perspective was articulated by radicals in the 1970s, outside academia see for example Zerowork 1975, specifically Paolo Carpignano, “US Class Composition in the Sixties,” Zerowork 1 (1975), http://libcom.org/library/us-classcomposition-sixties-paolo-carpignano-zerowork. Also Jeremy Brecher, Strike!, (PM Press, 2014).

54For more on FAP see Felicia Kornbluh, “Is Work the Only Thing That Pays The Guaranteed Income and Other Alternative Anti-Poverty Policies in Historical Perspective,” Northwestern Journal of Law & Social Policy 4 (2009): 61; Daniel P. Moynihan, The Politics of a Guaranteed Income: The Nixon Administration and the Family Assistance Plan, 1st ed. (New York: Random House, 1973); Brian Steensland, The Failed Welfare Revolution America’s Struggle over Guaranteed Income Policy (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2018); Jill Quadagno, “Race, Class, and Gender in the U.S. Welfare State: Nixon’s Failed Family Assistance Plan,” American Sociological Review 55, no. 1 (1990): 11–28.

55Kornbluh, The Battle for Welfare Rights.

56Welfare Fighter Dec 1969: 2. West Papers, Box 25, Folder “Publications.”

57“5500 UP the Nixon Plan” West Papers, Box 25, Folder 13.

58West Papers Box 25, Folder 13.

59Welfare activists were plenty aware of the ways their gender, and particularly their motherhood, in addition to their race and class, rendered them especially vulnerable to exploitation in the labor market. However, as Piven and I have argued elsewhere (“The Radical Feminist Legacy of the National Welfare Rights Organization”) the movement generally did not seek to improve women’s chances in the labor market or to seek remuneration for housework, but rather provide all poor people with the freedom to eschew employment. The persistent argument that welfare activists sought a gendered division of labor, encouraging work for men, and childrearing in the home for women (see Sherwin and Piven, “The Radical Feminist Legacy of the National Welfare Rights Organization” for a summary and retort of these arguments) is not born out in the archival record.

60With the exception of our article, Sherwin and Piven, “The Radical Feminist Legacy of the National Welfare Rights Organization,” scholarship examining the NWRO’s alternative to FAP has overlooked this profound analytic intervention entirely. For example, Kornbluh summarizes this groundbreaking document and recounts only, “in an April 1970 version of the NWRO Guaranteed Adequate Income plan, the activists offered a list of principles that they saw as essential to national welfare reform, beginning with adequate income as a ‘national goal’ and a timetable for reaching a basic income level of $5,500 per year. They sought the addition of emergency grants and regular cost of living increases to the ‘flat’ guaranteed income in FAP” (The Battle for Welfare Rights, 153). The powerful critiques of wage work contained within it are ignored entirely by the scholarly record.

61West Papers, Box 27, Folder 14.

62Weeks, The Problem with Work, 10.

63Ibid.

64Herbert J. Gans, “Positive Functions of the Undeserving Poor: Uses of the Underclass in America,” Politics & Society 22, no. 3 (September 1, 1994): 269–83, doi:10.1177/0032329294022003002.

65Richard Cloward comments given at the 1968 Congressional Hearing on Income Maintenance Programs.

66“WIN: Training for What?,” Piven Papers, Box 53, Folder 11.

67West, The National Welfare Rights Movement; Nadasen, Welfare Warriors; Sherwin and Piven, “The Radical Feminist Legacy of the National Welfare Rights Organization.”

68“WIN: Training for What?,” Piven Papers, Box 53, Folder 11, Smith College.

69Denton, “Neither Guns nor Bombs – Neither the State nor God – Will Stop Us from Fighting for Our Children”; Premilla Nadasen, “Expanding the Boundaries of the Women’s Movement”; Reese and Newcombe, “Income Rights, Mothers’ Rights, or Workers’ Rights?”; Triece, “Credible Workers and Deserving Mothers”; Sparks, “When Dissident Citizens Are Militant Mamas.”

70Kelley, Race Rebels.

71The Combahee River Collective, “A Black Feminist Statement,” Women’s Studies Quarterly 42, no. 3/4 (2014): 274.

72West, The National Welfare Rights Movement.

73This framing—centering on unpaid gendered labor rather than race—was adopted by the Wages for Housework movement, which looked to the welfare rights movement for inspiration. Mariarosa Dalla Costa for example wrote, “women refuse the myth of liberation through work. For we have worked enough. We have chopped billions of tons of cotton, washed billions of dishes, scrubbed billions of floors, typed billions of words, wired billions of radio sets, and washed billions of diapers by hand and in machines.” Mariarosa Dalla Costa, Women and the Subversion of the Community: A Mariarosa Dalla Costa Reader, trans. Richard Braude, ed. Camille Barbagallo (Oakland, CA: PM Press, 2019), 42. Existing scholarship on the WRM has compared the movement with Wages for Housework (Nadasen, Welfare Warriors); however, a central component of both movements was not the enshrining of and remuneration for gendered division of labor, but rather the refusal of work.

74West, The National Welfare Rights Movement; Orleck, Storming Caesars Palace; Nadasen, Welfare Warriors; Allison Puglisi, “Identity, Power, and the California Welfare-Rights Struggle, 1963–1975,” Humanities 6, no. 2 (June 2017): 14, doi:10.3390/h6020014.

75“NOW! National Welfare Leaders Newsletter,” June 6, 1968 West Papers, Box 25, Folder 10.

76NWRO Papers, Box 2068, Folder “Welfare Fighter.”

77“The Adequate Income Bill” West Papers Box 25, Folder 13.

78West Papers, Box 27, Folder 13.

79Sparer, “The Right to Welfare”; Davis, Brutal Need.

80“Everybody’s Got a Right to Live,” Smithsonian Folk Ways Recordings, https://folkways.si. edu/jimmy-collier-and-frederick-douglass-kirkpatrick/everybodys-got-a-right-to-live/ american-folk-struggle-protest/music/album/smithsonian. For example, Kerran Sanger argues “songs offered a compelling means by which activists could communicate among themselves and disseminate a positive self-definition, and provide answers to questions,” Kerran L. Sanger, When the Spirit Says Sing!: The Role of Freedom Songs in the Civil Rights Movement, 1st ed. (New York: Routledge, 2015), 8.

81Kelley, Freedom Dreams.

82West, The National Welfare Rights Movement; Kelley, Freedom Dreams, 121.

83West Papers, Box 25, Folder 10.

84West Papers, Box 25, Folder 13.

85West Papers, Box 27, Folder 14.

86Again, here the NWRO parallels Marx’s critiques of wage work when he insists the wage relation is entered into by the working class involuntarily and therefore a form of “economic bondage,” Karl Marx, Capital, 723. Arguments as to the unfreedom inherent to the proletarian condition appear throughout Marx’s work. In one example Marx writes, “The Roman slave was held in chains; the wage laborer is bound to his owner by invisible threads. The appearance of independence is maintained by a constant change in the person of the individual employer, and by the legal fiction of the contract,” 719.

87Wright, Envisioning Real Utopias, 4.

88Weeks, The Problem with Work: Feminism, Marxism, Antiwork Politics, and Postwork Imaginaries, 141.