Schilndler, Morphed into John Quincy Adams, Rescue Africans–A Retrograde Film Denies Black Agency and Intelligence, Misses What Really Happened, and Returns to the Conservative Themes of the Fifties; with an Account of What Really Happened, and a Few Words About Abolitionists as Fanatics

Introduction: Amistad’s Conservatism

Steven Spielberg's Amistad (1997 is a present-minded Nineties screed for white paternalism and cartoonified black instinctualism and for the archaic notion of history made by great men, particularly great white men After what amounts to a brief cameo uprising, which is presented as totally spontaneous and without prior thought or planning, Amistad denies the agency of the rebels, portraying them for most of the rest of the film as bystanders, while good and bad whites argue among themselves about whether or not to make them free. It's Spielberg's Schindlers List (1993) all over again, history seen not from the point of view of an alien oppressed them but rather mediated by a benevolent intervener who is more like us—the predominantly white (or, in the case of Schindler, gentile) audience—and who decides/or the oppressed whether they will live or die. J. Hoberman writes of Amistad in the Village Voice, "As in Schindler 's List, power resides with the white protagonist. In this respect, Amistad fits into a long line of Hollywood films of supposed social consciousness, such as Gentleman's Agreement, with its Jew-who-is-okay-because-he-is-just-like-everybody-else or the loathsome Mississippi Burning (1988), with its heroic FBI men who are presented as if they were the civil rights movement in 1964

Amistad’s schlock history is in tune with today's conservative and grim times in American culture and politics. And as we will see, its portrayal of the abolitionists brings back archaic themes from another conservative time, the Fifties: end of ideology, radicalism as a quest for martyrdom, true believers—the absurdity of radicalism. Since movies may well have more influence than the classroom does, Amistad will cast a large shadow over our history, over our understanding of slavery, and, more generally, over audiences' understanding of how political and social change comes about. I would argue that it is not, in the end, a good thing that we have this film. It is a bad thing, worse than nothing, a step back to interpretations that predate the Sixties. If you think Amistad is useful because, after all, it raises important issues, precipitates discussion, and yada yada, why not advance the discussion further by bringing back Gone with the Wind—whoops! they just did —and Birth of a Nation? What splendid opportunities to refute bigotry! Amistad has made millions, was nominated for two Academy awards, and would probably have done better but for the stiff competition I say, thank God for Titanic—with its straightforward message of people struggling ingeniously, against terrible forces, to survive.

My complaint against Amistad is not the professional historian's widely voiced displeasure with historical inaccuracies in the film. Certainly it is riddled with errors, some of them quite telling (see below). But most of the criticisms that I have heard on this front are mere pedantry. It really just doesn't matter that it couldn't have been snowing when Amistad was brought into port It just doesn't matter that American seamen are anachronistically portrayed as having beards and mustaches Far from being troubled by such matters, I find myself instead dismayed by the historians who have breached their trust with the public by focusing on often trivial inaccuracies while ignoring the larger themes of the film and the distorted history that it presents. Of course, the public will be confirmed in its judgment of academics as rarified fools if, in the face of the large interpretations in Amistad, the best we can do is quibble, while ignoring the point of the film

Inaccuracies aside, Spielberg is a historian, offering his interpretation of the past. He is free to focus on any part of the Amistad story that he wants to, interpreting the past in his own way, just like any other historian. Our job is to look at his history not simply as a collection of individual facts but also as an interpretation, arising from and promoting his values and politics, and to criticize his history. Yes, we can criticize different versions of history: I have no patience with postmodernist notions about different narratives in the face of supposedly unattainable truth, such as the idea that there is no truth of Hiroshima or Auschwitz, just different stories. There is a truth of Amistad: That truth is violent uprising against enslavement. And to say that movies are just show biz and that they therefore invite a different set of standards is absurd. If Spielberg had portrayed blacks as munching on watermelons and tossing the seeds in the air, would we say, "Oh well, that's entertainment?" To say "It's the times, that's the way movies have to be made" is to suggest that the times dictate that we also give up on such controversial issues as affirmative action and surrender to rampant racism and sexism and all the other vile values that historians looking back will see as ascendant in this period. Those who think that it's unfair to criticize Spielberg for making the movie that conservative times suggest might as well say that it's wrong to stand up against other manifestations of contemporary political recidivism because these are what the times indicate And although the rerelease of Gone with the Wind at this time is an ominous sign, some other recent films show us that movies don't have to simply bend with the worst prejudices of the time

Of course entertainment comes from a point of view and conveys values, so it is important to ask: Just what kind of values and politics are conveyed in Amistad? Looking at the ideas behind Amistad will tell us much about the social thought of the times we live in, since Spielberg is a somewhat mindless weather vane. As we will see, he has in the past bent with very different winds: I'll contrast with Amistad the Sixties values of Spielberg's Jaws, which I find different and preferable.

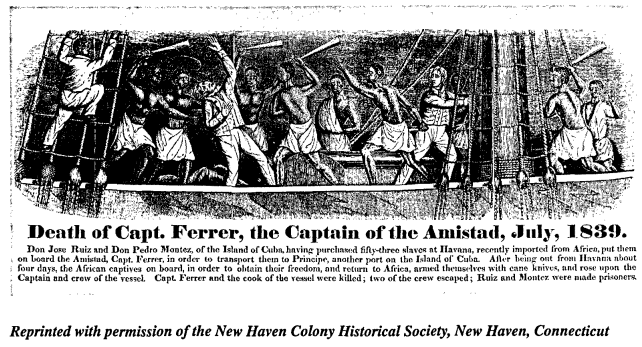

Reprinted with permission of the New Haven Colony Historical Society, New Haven, Connecticut

The Central Problem: Rebellion as Cameo

Am I missing the point? Is the movie really about resistance and protest? I asked my students who had not seen Amistad what it was about. Most of them thought it was about a shipboard rebellion. The expectation that Amistad would be about rebellion is an understandable error, since the central reality of the actual Amistad events is a shipboard rebellion. In fact, the rebellion takes only four minutes and twenty-six seconds of this long movie. Spielberg has chosen to place the resistance if not offstage, at least in a very small compartment. In flashback, Amistad later portrays successfully—even memorably—the horrors of the Middle Passage. But a depiction of horrors is not a depiction of rebellion.

This disproportion has been reproduced in many recent discussions and versions of Amistad, in which the uprising itself is given only brief attention Anthony Davis's opera, Amistad, performed by Chicago's Lyric Opera beginning in November 1997 follows the same pattern. And we have reason to wonder whether the replica of the original vessel being constructed at Mystic Seaport in Connecticut by Amistad America Inc. will be used forthrightly to celebrate a violent uprising or will be tuned down into a celebration of the legal process Amistad America Inc. describes its mission as "to teach the lessons of history, cooperation and leadership inherent in the Amistad incident and its legacy. Speaking at Mystic Seaport in March 1998, Ambassador John Leigh of Sierra Leone saw in the Amistad events a story—incredibly—of black-white cooperation He, too, missed the boat.

Returning to the cameo quality of the uprising in Amistad: As part of the process of reducing the rebellion in this way, Spielberg makes it into an unpremeditated outburst, without planning or prior root in events on shipboard. As we will see, the effect of this is to ignore the intelligence behind the uprising and to focus instead on what thus appears to be instinctual and stereotypically animalistic behavior.

Spielberg’s Portrayal of the Uprising and Subsequent Events

The film begins in medias res. In the dark, punctuated by lightning but no thunder, a man we will later learn is Cinque labors, sweating and breathing heavily, to pry a nail out of Amistad. He seems to be alone. His hand bleeds. He succeeds, holds up the nail and looks at it. He uses the nail to release himself from his locked iron collar. Now, the thunder booms. Immediately, without an instant's hesitation, Cinque and the other Africans break open a crate containing cane knives. They shout at each other, but we cannot understand what they are saying. They emerge on deck, shrieking and killing. They seem to disagree among themselves. They take the vessel. All this has lasted less than four and one-half minutes.

The short rebellion presented by Spielberg is shown as spontaneous, rising out of the air and without prior planning or rationale This is like the older historiography of riot and much contemporary journalism (especially television) about protest and riot, which begin at the moment of physical violence. This approach reports an action that is made to appear without thoughtful root and therefore appears to be inexplicable and crazy.

In addition to reducing the rebellion to a cameo, the rest of the two-and-one-half hour film, after the uprising, is about struggles among white people to determine whether blacks will be granted their freedom or sent off to die. (There are a few flashbacks to Africa and scenes on the Middle Passage.) Amistad is about a courtroom confrontation among whites rather than a rebellion of blacks against whites who seek to enslave them. The Africans are, by and large, only witnesses to these struggles, often reduced to trying to decode the dramatis personae: "Have you figured out who he is?" one asks another in the courtroom. The film's penultimate scene shows shouting blacks fleeing the "slave fortress" at Lomboko liberated by British military action, with the Union Jack flying high. British cannons destroy the fortress—which blows up like the finale of Zabriskie Point (1970), with pieces flying around. Could the message— benevolent action by whites, and black passivity—be any clearer

The Absence of Black Agency

This is a little like the version of history that is emerging in which Lyndon Johnson gives blacks their rights in 1964 What's missing in Amistad is a sense of black agency. For the classic definition of the term "agency" we must go back to more enlightened times, the years of the birth of the New Left and its founding work of history, E. P. Thompson's The Making of the English Working Class (1963). Thompson writes of "the degree to which they [workers] contributed, by conscious efforts, to the making of history" (p. 12). From this notion came the turn away from history as the history of Great White Men, and the development of social history. And this historical reinterpretation, beginning in the 1960s, was no ivory-tower thing: Part of its persuasive power rested on the fact that it resonated with the reality in those years of people in the streets making their own history. Agency was the central idea, both in the movement and in the emerging scholarship. With Amistad, we have a movie that, like so much in contemporary culture, seeks to take back the Sixties.

Reinforcing the absence of black agency is the film's focus on Cinque as individual hero: "It is the story of Cinque ... whose revolt... led to a landmark Supreme Court decision. Grabeau, described by a contemporary source as "the next after Cinque in command of the Amistad," is simply written out of the film, exaggerating the singularity of Cinque's role The learning kit Amistad: A Lasting Legacy, distributed to educators by the makers of Amistad, focuses on heroes—Cinque and John Quincy Adams—and seems explicitly to reject the role of popular movements of resistance, to focus on leaders rather than groups. Activity One, concerning "Heroes," describes itself as "run[ning] somewhat counter to current trends in the study of history," and it clearly turns its back on the social history that has developed in the last thirty-five years We can also see a denial of agency in the film's unwillingness to come to terms with the rebels' intelligence and planning.

And those who see as resistance black people helping their white lawyers to formulate legal arguments seem obtuse about the meaning of resistance. The moment when the blacks stand up in the courtroom and chant for their freedom—"Give us free!" "Give us free!"—is moving precisely because it hints at the agency that is generally missing from the movie. (The learning kit, focusing on individual heroism, klutzily misperceives this wonderful collective moment: "Cinque disrupts the court.") And it may be that Spielberg's insertion into the story of an invented character, black abolitionist Theodore Joadson, is another token effort by the director to compensate for the overall lack of black agency in the film

Not the First Discovery of Amistad

As part of the mood of the Sixties, the Amistad story was a popular theme among insurgents of the time. Coproducer Debbie Allen has been saying that the story of Amistad was unknown before she came upon it, and Amistad promotional materials call the Amistad events "a forgotten past." What a failure to credit those who fought for black history earlier! Amistad was known to activists of the Sixties, both black and white. It was there, for instance, in a fine journal of black history and culture by that name, two issues of which had been published in paperback by Vintage Books of Random House while coproducer Allen was in college Although claiming that Amistad was unknown before she came upon it, Allen acknowledge s that her first information came in her reading in of "two volumes of essays and articles, titled Amistad I and I I, written by African-American writers, historians and philosophers," which are not otherwise described (promotional materials). The film's learning kit omits mention of the journal from its list of relevant readings.

Beyond the journal, the story of Amistad was there in the Sixties (and Seventies) in frequent invocations including poetry, and, for better or for worse, it was the assumed name of the leader of the Symbionese Liberation Army. And there were, as I recall, some baby Cinques, like the baby Ches of the time, and the baby Emmas of today. It's tragic that an Amistad film was not made in those times. It would have had very different themes and accents than Spielberg's version.

An Alternate Scenario: Rebellion as Central

But let's imagine that film—the one that might have been made in the Sixties, the one Spielberg could have made today had he been willing (like Warren Beatty and Peter Weir) to stand up against the conservative Nineties tide, the film that we may hope will one day be made. Imagine a two-and-one-half-hour movie about Amistad that deals for two hours and twenty-nine minutes with Africa and the taking of the blacks and culminates in the planning, organization, and carrying out of the uprising, saving the trials for an epilogue

In imagining the crafting of such a film, our first step must be to get back to the basic facts of the uprising. This will help us to understand what Spielberg left out and how badly he distorted the story. In what follows, I will present first a brief narrative of what happened in the days leading up to the Africans' attack and their seizure of the vessel. Then I will move on to an analysis, looking in particular at the ideas and themes that could have been presented in a more exciting and truthful film than the one that Spielberg made.

The

The fifty-three Africans boarded Amistad at Havana on June 28, 1839. Below deck, the cargo included crockery, copper, dry goods, "Fancy articles for Amusement or luxury— and boxes "that contained weapons: sugar cane knives with handles consisting of square pieces of steel an inch thick, and attached to blades two feet long that gradually widened to three inches at the end.

Amistad weighed anchor near midnight, then set out for Puerto Principe, down the coast of Cuba. Grabeau later testified that at night the Africans were kept in irons ("placed about the hands, feet and neck") Cinque said "the chain which connected the iron collars about their necks, was fastened at the end by a padlock. The Africans' "allowance of food was very scant, and of water still more so. They were very hungry, and suffered much in the hot days and nights from thirst. In addition to this there was much whipping." Abolitionist George Day of New Haven basing his account on the Africans' statements, said that they "were cruelly treated on the passage, being beaten and flogged, and in some instances having vinegar and gunpowder rubbed into their wounds, and that they suffered intensely from hunger and thirst. Another abolitionist account said, "When they took any water without leave, and at other times, they were severely scourged by order of their masters.

During the day, Grabeau recalled, some of the irons were removed The Africans were allowed on deck from time to time. At one such point, Cinque had an ominous conversation with the schooner's mulatto cook, Celestino:

[H]e used sign language to ask the cook what would happen to them. In cruel jest, Celestino grinned and pointed to the barrels of beef across the room and then to an empty one behind him. Upon arrival in Puerto Principe, he indicated with his fingers, the Spaniards planned to slit all the slaves' throats, chop their bodies into pieces, salt them down, and eat them as dried meat

Howard Jones's account proceeds, describing Cinque's reaction to the cook's remark: "Cinque stumbled out of the kitchen, stunned by Celestino's crude revelation and yet furious with himself and with the cook's arrogant manner. Cinque should have known better than to talk to him; Celestino had once struck him for no apparent reason.

At this point, Cinque found a way to free himself: "Finding a nail, Cinque hid it under his arm, determined at the first opportunity to pick the lock on the iron collar around his neck and make a strike for freedom.

The opportunity was to present itself on July 1. As far as the captain and crew were concerned, "For the four first days every thing went on well. But that night, between eleven and twelve, after the captain went to sleep, the night turned stormy. "There was no moon," one of the Spaniards would later recall: "It [was] very dark. The clouds covered the moon, and the storm forced the crew to lower the sails for several hours

So it was that between 3:00 and 4:00 A.M. on July 2, with the sky still rainy and darkened by heavy and some of the crew asleep the successful rebellion began Cinque opened the padlock, and then the other irons The Africans emerged on deck with their cane knives and attacked their captors. We have a vivid contemporary picture of this, showing the Africans brandishing their knives "Throw some bread at them!" shouted the awakened captain, seeking to pacify them and thinking that was all they wanted The captain and the cook were killed, as were perhaps one or two of the rebels, and others wounded Within a few minutes, the Africans were in control of Amistad.

Consciousness and Communication

E. P. Thompson's definition of agency, it will be recalled, spoke of conscious efforts from below to make history. Even the bare outline offered above shows that the uprising in Amistad was thoughtful, resourceful, intelligent, and planned, involving communication among the rebels and a sense of injustice—in other words, it was conscious. To show this, we will return to the narrative, but this time we will look at what lies behind it. In particular, we will find that there was communication about intent and strategy among the rebels before and during the rebellion. Although the evidence is ample, we may not find detailed evidence of such communication—no surprise in a conspiracy. But we will work from the simple assumption that people talk to each other. The assumption that they do not is so illogical and unrealistic that evidence would be needed to defend so dubious a proposition

Spielberg allows the Africans a certain amount of verbal communication, but he uses a special device that has the effect of masking their communication from the audience and thus radically lessening its significance: In the early scenes and through much of the rest of the movie, we literally do not know what they are talking about. Carla Peterson has acutely noted the absence of subtitles for the Africans, which, as Robert Sklar has pointed out, has the effect of blocking us from their personhood and inner thoughts Thus, as soon as Cinque has unshackled himself and the Africans are breaking into the box of knives, they are shouting to one another—incomprehensibly. When the Spaniards talk, they are given English subtitles. After the Africans successfully seize the ship, they are seen quarreling among themselves, but we must rely on English subtitles that translate the Spaniards' version of what the Africans say. This further distances us from the notion that there might be conflicts about strategy among the Africans, reflecting intelligent thought. In other words, the Spaniards mediate between us and the Africans. The Africans thus remain, by the film's imposed definition, literally inarticulate. Only after twenty-two minutes of the film do the Africans begin to acquire English subtitles. But thereafter the titles go away, come back, and go away again. At one point later on, Cinque is shown in a passionate but incomprehensible outburst, denouncing lawyer Baldwin while drums beat and a bonfire burns. If we can shake ourselves free of the notion that Spielberg has somehow done a good thing with this movie, we can clearly see the perpetuation of old racist stereotypes.

The Availability of Weapons on Board Amistad

Was the taking of the cane knives by the Africans planned or serendipitous? The film shows the rebels, once freed of shackles, going immediately for the crates of cane knives, breaking into them and taking them. If this had actually been the case, they would have had to have known in advance that there were knives in the boxes, and they might even have planned their uprising at least in part in light of their knowledge that weapons were available. How did they find out? We don't know, but we do know that they knew about them and communicated about them before the uprising. What appears to be spontaneity in the film in fact demonstrates the reverse

The Cook’s Threats That the Africans Would Be Made into Meat

All the evidence we have is that these threats were taken seriously by the rebels, and their awareness was a crucial element in leading them to rebel. Although this event is omitted from the film, we know the impact this had on Cinque: Jones says that "Cinque claimed that he had led the others in revolt because the cook said they would be eaten upon reaching land. Kinna indicates that Cinque told the others about the incident with the cook: "[C]ook say we good to eat—we very unhappy all night— we 'fraid to be killed. Grabeau—who was written out of the film—"declared that this had 'made their hearts burn,'" and he could not be plainer about the causality: "To avoid being eaten, and to escape the bad treatment they experienced, they rose upon the crew with the design of returning to Africa. And we have letters from two of the Africans to John Quincy Adams that focus on this event. Kale writes: "Cook say he kill, he eat Mendi people—we afraid—we kill cook. Kinna writes: "Bad people say Mendi people murderers because we kill Captain and cook. If we have knife and come to America people and say I kill and eat, what America people do? An abolitionist who interviewed the Africans said that after the cook's threat, "[t]he Mendians took counsel, and resolved on attempting to recover their liberty. The Africans attached great significance to this event, and its omission from the film falsely exaggerates the spontaneity of the uprising, while undermining the rationality and underlying principles of their act.

The Conjunction of Circumstances on the Night of the Uprising

Since anything can be imagined, it is imaginable that the rebellion was conceived and executed impulsively within a few minutes. But the conjunction of circumstances at the time of the rebellion strongly suggests that people had made their plans and were waiting for an opportunity. When they struck, the captain and some of the crew were asleep and the night was dark and stormy, with the noise making it easier for the rebels to communicate with each other without the men on deck detecting their action. All this gave them the opportunity to surprise their enemies: "Do not know how things began; was awoke by the noise.

Immediate Action Implies Planning

As indicated above, the rebels would not have gone straight for the crates of cane knives without advance knowledge that the knives were there. Similarly, their rapid movements on the night of July 1-2 imply prior organization and planning.

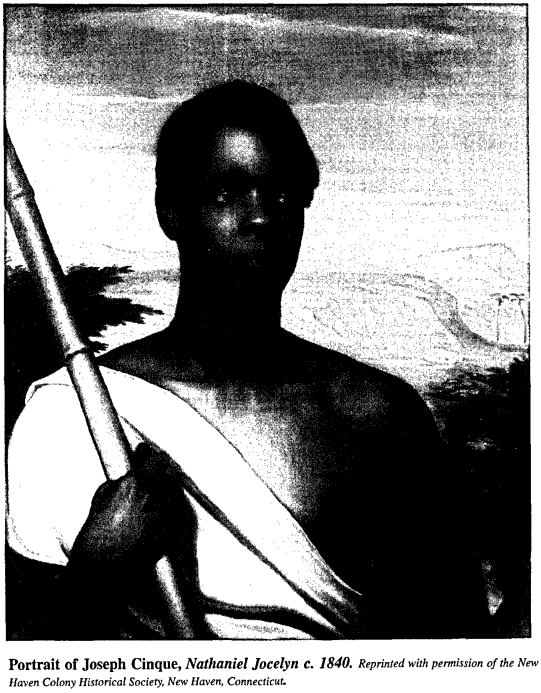

Portrait of Joseph Cinque, Nathaniel Jocelyn c. 1840.

Conclusion: “Animal Propensities” Versus “Intellectual Faculties”

Contemporary descriptions of Cinque indicate:

The lower animal propensities do not constitute the leading elements of his character...

[He has] a love of liberty, independence, determination, ambition, regard for his country, and for what he thinks is sacred and right; also, good practical talents and powers of observation, shrewdness, tact, and management, joined with an uncommon degree of moral courage and pride of character

His countenance, for a native African, is unusually intelligent, evincing uncommon decision and coolness, with a composure characteristic of true courage, and nothing to mark him as a malicious man ... his moral sentiments and intellectual faculties predominate considerably over his animal propensities. He is said, however, to have killed the Captain and crew with his own hand, by cutting their throats

We have no trouble recognizing the racism summarized in the notion of "animal propensities." However, we have seen much evidence, in Cinque as well as in the others, of "intellectual faculties." But we have also seen that in his description of the uprising, Spielberg comes down heavily on the side of "animal propensities." The alternate scenario that I have suggested, and its special themes, bring us back to intelligent rebels.

And the evidence supports the notion of thoughtful rebels, who did, indeed, engage in a conspiracy. They "take counsel": Kinna says, "[W]e consider" Kale says, "Mendi people think, think, think. And we have seen something of what they thought about: not, as the captain believed, simply bread, but rather the cook's threats, the bad treatment, getting their liberty, and returning to Africa.

Imagine a movie, rooted in the rebels' principles and informed by the historical sources and the kind of analysis offered above. It would be substantial and thrilling and would leave us at the end with at least a clue about answers to such questions as those that I have posed above, as well as others: How much support did the uprising have? Who participated, and who didn't? How do you organize an uprising under such conditions? (Perhaps some of these questions are answered in the Mende dialogue in the opening scenes where there is much talk but no translation.)

Then, after two hours and twenty-nine minutes of my hypothetical film about the uprising, in the last minute, an epilogue in print would scroll by on the screen, dealing briefly with the subsequent events that the film as presently made focuses on almost totally: the trials In the film that I have suggested, Spielberg as historian would have focused on black agency and group action rather than, as in the film that he made, focusing on white paternalism: whites freeing blacks. The things Spielberg presents did in fact happen: black resistance and then white activism. Why does Spielberg choose to focus on the one at the expense of the other and to ignore evidence of agency, intelligence, and consciousness? In the age of postmodernism, one may still conclude that there is in fact a truth of Amistad: violent and courageous resistance.

Jaws and Titanic Versus Amistad

In a way, the Spielberg of the Seventies did make the film I have outlined. He called it Jaws (1975). Jaws, like Amistad, reflected the feeling of the times. But those were different times. Quint (Robert Shaw), with all his manliness, is shown to be dangerously crazy, and the terrible shark is overcome not by him but by a new kind of not-manly hero: Brody, a somewhat inept former New York cop who can't swim (Roy Scheider), and Hooper, a small nerdy ichthyologist (Richard Dreyfuss), still partly encased in the character of the previous year's Duddy Kravitz (1974). It is these two, physically limited but resourceful, who overcome the terror. The agency that is lacking in Amistad is the central theme in Jaws. In the latter, the weak overcome the strong; in the former, after the uprising—reduced to a prologue—the best the people who argued this out with me on the American Studies Internet list were able to produce in the way of agency in the film was the notion that the Africans influenced their lawyers If Spielberg had made Jaws the way he made Amistad, the shark would have been dead in the first five minutes, and the rest of the film would have been about the negligence suit against Quint

Jaws is more like Titanic than it is like Amistad. In Titanic, Jack isn't waiting for somebody else to save him and Rose. He is active and resourceful, and so is Rose, sometimes (despite the sexist overlay of dependence in the portrayal). Amistad is more like Mississippi Burning, with blacks as beneficiaries of the FBI's generosity. And again, this whole complex should remind us of Schindler, who saves "his" Jews.

Amistad Ridicules Abolitionists and Radicalism

Finally, the film ridicules abolitionists. They are portrayed as zealots, fanatics, and True Believers, and even the blacks whom they defend in the movie think them absurd. Lewis Tappan, the abolitionist, is portrayed as saying "this war must be raged on the battlefield of righteousness," and at one point he wishes for martyrdom for the Africans. Roger Baldwin, in actuality an abolitionist but portrayed sympathetically by Spielberg as earthy, practical, non-ideological—just a property lawyer without high principle—dimisses principled struggle by saying tersely, "Christ lost." The Africans look at the abolitionists and say that they "look like they're going to be sick," and "They're entertainers." "Why do they look so miserable?"

This descriptive complex is familiar to anyone who lived through the conservatism of the 1950s, with its consensus historiography and its attack—as part of the anti-Communist crusade—on all radicalism. And now, with Amistad, it has returned. Spielberg's abolitionists are derived from Daniel Boorstin, with his attacks on alleged deliberate quests for martyrdom and his support of the practical and non-ideological over the principled; Daniel Bell, preaching the end of ideology; Nixon's favorite worker, Eric Hoffer, with his attacks on radicals as True Believers; and Stanley Elkins, who saw abolitionists as irrational and driven by guilt

In conclusion: Let's wake up, the Fifties are back, and Spielberg's Amistad tells us which way the wind is blowing. It will take a movement, as it did last time, to wash these conservative ideas away. Let's make one!

Notes

An earlier version of this article was presented at the New England American Studies Association Conference plenary session, Mystic Seaport, Mystic, Connecticut, May 9, 1998. The author expresses his gratitude to Christopher Z. Hobson, Joanne Landy, and Naomi Weisstein. Copyright Jesse Lemisch, 1998.

1With apologies to Vincent Harding's excellent essay, "You've Taken My Nat and Gone," in John Henrik Clarke, ed., William Styron 's Nat Turner: Ten Black Writ- ers Respond (Boston, 1968), pp. 22-33. Harding, in turn, quotes Langston Hughes: "You've taken my blues and gone" (ibid., p. 32).

2Amistad is available on video.

3For an earlier critique of this tendency in historiography, see Jesse Lemisch, "The American Revolution Bicentennial and the Papers of Great White Men," American Historical Association Newsletter 9 (November 1971), pp. 7-21. Also see Lemisch, "The Papers of a Few Great Black Men and a Few Great White Women," Maryland Historian 6 (Spring 1975), pp. 60-66.

4December 16, 1997. Without sensing the irony in her statement, Amistad coproducer Debbie Allen says that seeing Schindler's List persuaded her that Spielberg was "a filmmaker who could understand and embrace the project [Amistad]'' The promotional material that contains this quotation also indicates a good deal of continuity between the "creative teams" of the two films.

5Arts and Entertainment Cable Network documentary, "Hollywood, Jews, Movies and the American Dream," March 22, 1998; based on Neal Gabler, An Empire of Their Own: How the Jews Invented Hollywood (New York, 1988).

6For a good discussion, see Jonathan Rosenbaum, "A Perversion of the Past (Mississippi Burning)," in his Movies as Politics (Berkeley, 1997), pp. 118-124.

7Bernard Weinraub, "Scarlett, Rhett and the Old South at Their Most Colorful," New York Times, June 25, 1998, reports the opening of the film on that date in two hundred theaters. The president of Turner Entertainment says, 'Ted just loves this movie . . . He's the force behind it." (Thanks to you, too, Jane.) Most of Weinraub's piece deals with technical enhancements in this version, and not a word is said about the film's notorious racism, which has been widely condemned since its original release in 1939. A later Times report broaches the subject of racism, but only in an indirect and apologetic way: "Its politics—to the extent it has any—are at a decent remove from the blatant racism of "The Birth of a Nation,' the D. W. Griffith silent-film masterpiece. But with the exception of a couple of sarcastic remarks made early on by the renegade aristocrat Rhett Butler, there is nothing in 'Gone With the Wind' to indicate that the pretty world being destroyed is anything but perfect. With the passage of time, the movie has been taking on the airs of the imperious Lady Bracknell, who simply ignores everything that exists beyond Belgravia." Vincent Canby, "A Classic That's as Changeable as the Wind," New York Times (Arts and Leisure section), June 28, 1998. A week later ("Taking the Children," New York Times [Arts and Leisure section], July 5, 1998), the Times was recommending the film for children, while noting secondarily, "The film, almost 60 years old, reflects some very negative racial attitudes of its time." Although the reissue of Gone with the Wind (GWTW) would have to have been in process for some time, it seems reasonable to speculate that a critical reception for Amistad might have made reissuing GWTW less commercially appealing. If, in addition, there is critical acquiescence to GWTW, how far behind will an enhanced (colorized?) Birth of a Nation be?

8But it should be noted that six months after Amistad's release, the New York Times described it on May 19, 1998, as "a commercial disappointment, grossing only [sic] $44.3 million."

9Review by Sally Hadden, H-Net Humanities and Social Science OnLine, January 1998.

10Eric McKitrick, "John Quincy Adams: For the Defense," New York Review of Books, April 23, 1998. Some other cute' anachronisms include: Roger Baldwin tells Cinque, "I need you to tell me"; Baldwin responds to a favorable verdict by thrusting his arm in the air and shouting, "Yessss!"

11For an important exception, see Eric Foner, "Hollywood Invades the Classroom," New York Times, December 20, 1997.

12Some, in effect, do say this: For critiques, see Jesse Lemisch, "Angry White Men on the Left," New Politics 6 (2) (Winter 1997), pp. 97-104; Jesse Lemisch, "Social Conservatism on the Left: The Abandonment of Radicalism and the Collapse of the Jewish Left into Faith and Family," Tikkun 4 (3) (May-June 1989).

13Not considered here, but certainly worth mentioning as additional evidence that Hollywood can indeed make films that challenge these retrograde times, are two 1998 films: Warren Beatty's Bulworth and Peter Weir's The Truman Story; and, in 1997, Wag the Dog and The Rainmaker. Truman seems to me more than simply the literal attack on the role of media that critics have seen in it but rather a 1984 for our times, a critique of totalitarianism. In some respects, these films suggest that Hollywood—or at least some of it—is ahead of the rest of the culture.

14Eric McKitrick in New York Review of Books, April 23, 1998; symposium on "Amistad: Slavery, Justice and Memory," Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History and Association of the Bar of the City of New York, New York City, April 25, 1998.

15Libretto by Thulani Davis. New York Times, February 18, 1998.

16The keel was laid March 8, 1998. See Sally Hadden, "Redefining the Boundaries of Public History: Mystic Seaport Goes Online and On Board with Amistad," Organization of American Historians Newsletter, May 1998, p. 13; "Slave Ship to Be Rebuilt as a School," New York Times, March 9, 1998.

17Available: www.amistadamerica.org.

18"Slave Ship to Be Rebuilt as a School."

19Of course slavery is horrible and offers in itself ample reason for rebellion. But we know that, unfortunately, horror is generally not sufficient in itself to cause or explain specific acts of rebellion.

20For classic critiques, see George Rudé, The Crowd in History (New York, 1964), and E. P. Thompson, "The Moral Economy of the English Crowd in the Eighteenth Century," Past and Present, 50 (February 1971), pp. 76-136. See also Jesse Lemisch, "Jack Tar in the Streets: Merchant Seamen in the Politics of Revolutionary America," William and Mary Quarterly, 3d ser., 25 (July 1968), pp. 371-407.

21Represented in the film by El Morro in San Juan. This representation is something of an exaggeration. Lomboko (Dombokoro) was simply "a square with a stockade . . . the factory containing the goods was upon each side; in the middle were the barracoons." Trial of Pedro de Zulueta, quoted in Adam Jones, From Slaves to Palm Kernels: A History of the Galinhas Country (West Africa) [Studien zur Kulturkunde 68, Wiesbaden, 1983], p. 51, q.v. for a description of a barracoon. For an illustration of a barracoon at Lomboko, see Illustrated London News, April 14, 1849; "Exploring Amistad" (available: www.amistad.mysticseaport.org). See also Jones, From Slaves to Palm Kernels, figure 2, for a map; pp. 80-83 for British actions leading to "The Destruction of the Atlantic Slave Trade" on the Galinhas coast; and plate 2 for a sketch of the destruction of barracoons in 1840. I am indebted to Stanley Engerman for calling Jones's work to my attention.

22There seems a parallel here with Jonathan Rosenbaum's statements concerning Mississippi Burning: "Two FBI agents [are] the only good guys in sight [p. 119] . . . The blacks themselves are given no voice . . . They're essentially treated like children [p. 120]."

23For a recent counter to this trend in another area, see Lawrence S. Winner's statement: "The history of nuclear arms controls without the nuclear disarmament movement is like the history of U.S. civil rights legislation without the civil rights movement." Resisting the Bomb: A History of the World Nuclear Disarmament Movement, 1954-1970 (Stanford, 1997), vol. 2 of The Struggle Against the Bomb.

24Taken from the film's "learning kit," Amistad: A Lasting Legacy (1997), which was distributed to educators by the makers of Amistad. For a critique of the kit, see Eric Foner, "Hollywood Invades the Classroom." I have no intention to denigrate Cinque's heroism and leadership, only to put it in the context of a group effort. One contemporary report describes Cinque as "the master spirit of this bloody tragedy." John Warner Barber, A History of the Amistad Captives: Being a Circumstantial Account of the Capture of the Spanish Schooner Amistad, by the Africans on Board . . . (New Haven, 1840), p. 2 (Pagination follows the bracketed numbers given in www.Amistad@MysticSeaport.org).

25Barber, History of the Amistad Captives, p. 8 (picture and biographical sketch). (Grabeau's Mende name was Gilabaru.) Howard Jones, Mutiny on the Amistad: The Saga of a Slave Revolt and Its Impact on American Abolition, Law, and Diplomacy (New York, 1987; rev. ed., 1997), describes Grabeau: "Cinque worked closely with a fellow captive named Grabeau in making preparations for an insurrection" (p. 24); "Cinque, along with Grabeau and Burnah, had taken command of the Amistad" (p. 25); John Quincy Adams called Cinque and Grabeau "the two chief conspirators" (p. 154). Nonetheless, Grabeau does not appear in the film; see the credits under the headings "Amistad Africans" and "Additional Amistad Africans."

26For another narrowing of the focus to Cinque, note Activity Four of the learning kit: "John Quincy Adams defends Cinque before the Supreme Court."

27Note that this invented character is presented as a prosperous businessman. This seems, like Schindler and the white abolitionists, another way in which Spielberg mediates between the audience and oppressed people via characters who are less alien to the majority audience, more "white."

28This important product of more radical times ought to be remembered. Amistad: Writings in Black History and Culture made its debut in February 1970, containing a short description of the Amistad uprising and articles (on other topics) by C.L.R. James, Vincent Harding, Ishmael Reed, Langston Hughes, Chester Himes, and others. Published by Random House as a Vintage Book and edited by John A. Williams and Charles F. Harris, volume 1—dedicated to Langston Hughes—offered a critique of what it called "'intellectual' racism" (p. viii). Issue 2 (1971), dedicated to Richard Wright, included material by Wright, Haywood Burns, Toni Morrison, John Oliver Killens, W.E.B. Du Bois, Basil Davidson, and others.

29However, a Hartford Courant reporter who interviewed Allen (December 3, 1997) says that she "first came across the story in a collection of academic essays in 1978."

30As well as in history. See, for example, William A. Owens, Slave Mutiny: The Revolt on the Schooner Amistad (New York, 1953); Christopher Martin, The Amistad Affair (New York, 1970); Mary Cable, Black Odyssey: The Case of the Slave Ship "Amistad" (New York, 1971).

31For a possible qualification, although one that would still give the trials sharply reduced attention, see below.

32The following narrative and discussion is based on my reading of: (1) Howard Jones, Mutiny on the Amistad; (2) the rich collection, amounting to more than 400 documents (including newspapers, personal papers, court records, popular media, and maps), available at the Library section of "Exploring Amistad," including John Warner Barber, History of the Amistad Captives (under "Popular Media"); (3) other sources, as cited herein. For visual materials, see "Exploring Amistad," "Gallery." (For a discussion of the web site, see Hadden, "Redefining the Boundaries.") See also photographs of contemporary paintings and sketches of Cinque, Grabeau, Kale, Kinna, Margru, and Banna in Jones, Mutiny on the Amistad, after p. 154. Some years back, I urged historians not to dismiss ordinary people as "inarticulate" for lack of documentation but rather to look for historical situations that produce an outpouring of first-person documentation from below. See Lemisch, "American Revolution Bicentennial and the Papers of Great White Men," p. 15. Lemisch, "Listening to the 'Inarticulate': William Widger's Dream and the Loyalty of American Revolutionary Seamen in British Prisons," Journal of Social History 3 (Fall 1969), concludes (pp. 28-29) by asking: If sources such as those which I found for the seamen's politics, loyalties and culture exist, "then is it not time that we put 'inarticulate' in quotation marks and begin to see the term more as a judgment on the failure of historians than as a description of historical reality?" Amistad is a prime example of the kind of historical situation that produces such documentation. The material available includes testimony and even letters from the Amistad Africans (see, for example, below, letters from Kale and Kinna to JQA) and visual materials. See also John Blassingame, ed., Slave Testimony: Two Centuries of Letters, Speeches, Interviews, and Autobiographies (Baton Rouge, LA, 1977), pp. 32-46, 198-208, including a letter from Cinque to President John Tyler, October 5, 1841, p. 42. In the sources, the Amistad Africans are neither inarticulate nor unintelligent, and we can see their faces.

33Charleston Courier, September 5, 1839. For other items, see Barber, History of the Amistad Captives, p. 2.

34Jones, Mutiny on the Amistad, p. 24. For contemporary illustration, see above, p. 59.

35For this and the following, see Barber, History of the Amistad Captives, p. 18.

36See New Haven Record, October 12, 1839, in Blassingame, Slave Testimony, pp. 199-200 for this and the following.

37See Jones, Mutiny on the Amistad, p. 85.

38George Day to New York Journal of Commerce, October 8, 1939; Barber, History of the Amistad Captives, p. 17

39Philanthropist, December 29, 1841, in Blassingame, Slave Testimony, p. 202.

40Barber, History of the Amistad Captives, p. 18.

41Ibid., p. 24. See below for Africans' descriptions of this event.

42Jones, Mutiny on the Amistad, p. 24.

43Ibid., p. 24.

44Barber, History of the Amistad Captives, p. 5.

45Barber, Mutiny on the Amistad, p. 5. See also Montes (in ibid.): "Between 11 and 12 at night, just as the moon was rising, sky dark and cloudy, weather very rainy, on the fourth night I laid down on a matress [sic]''

46Jones, Mutiny on the Amistad, p. 24.

47Ibid.

48Montes, in Barber, History of the Amistad Captives, p. 5: "Between three and four was awakened by a noise which was caused by blows given to the mulatto cook. I went on deck and they attacked me."

49Montes, in Barber, History of the Amistad Captives, p. 5.

50New Haven Record, October 12, 1839, in Blassingame, Slave Testimony, p. 200.

51Barber, History of the Amistad Captives, p. 59.

52Jones, Mutiny on the Amistad, pp. 24-25; Ruiz, in Barber, History of the Amistad Captives, p. 5.

53Jones, Mutiny on the Amistad, pp. 5, 25. Cf p. 126. Philanthropist, December 29, 1841, in Blassingame, Slave Testimony, p. 202.

54To be clear about this point, my contention is that the evidentiary presumption is in favor of communication and that explicit evidence would have to be produced to support the dubious notion that communication was absent.

55Presentations by Peterson and Sklar at Amistad Symposium, Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History and Association of the Bar of the City of New York, April 25, 1998.

56An hour and twenty minutes after the uprising scene, the film offers a clumsy hint that the rebels may have known of the knives in advance, but it presents this in a totally unpersuasive way. In a flashback, we see the Africans climbing up to board Amistad at Havana. Before Cinque, and above his head, we see a partially opened crate of knives being lifted on board. But the knives are displayed for the camera (actually tilted toward it)—the crate is open on top—in a way that would not make them visible to Cinque behind and beneath the crate. Nonetheless, at this point, Cinque has a premonition of rebellion. Since he has been shown as unable to see the knives, the scene suggests only a mystical perception on his part.

57Jones, Mutiny on the Amistad, p. 85.

58"Exploring Amistad" web site.

59New Haven Record, October 12, 1839; Blassingame, Slave Testimony, p. 199.

60"Exploring Amistad" web site, "Personal Documents," Kale to John Quincy Adams, January 4, 1841.

61"Exploring Amistad' web site, "Personal Documents," Kinna to John Quincy Adams, January 4, 1841.

62Philanthropist, December 29, 1841, in Blassingame, Slave Testimony, p. 202.

63Ruiz, in Barber, History of the Amistad Captives, p. 5.

64L. N. Fowler, "Phrenological Developments of Joseph Cinquez, Alias Ginqua," American Phrenological Journal and Miscellany 2 (1840), pp. 136-138, in "Exploring Amistad''

65Barber, History of the Amistad Captives, p. 2.

66Available: www.amistadamerica.org.

67Kale to John Quincy Adams, January 4, 1841.

68I could see giving the trials more than one minute, but the idea of reducing them to an epilogue seems to me to offer the reader for thoughtful consideration a solution symmetrical to the brief attention that Spielberg has given to the uprising.

69Robert L. Hall, "Reflections on the Amistad Affair in History and in Film, 1839-1997," Radical Historians Newsletter, December 1997, argues that there is in any case no evidence for this proposition. But note that there were some letters from the Amistad Africans to John Quincy Adams, in which they seem to be supplying information for use in his argument before the Supreme Court (above).

70There are some scenes in Amistad that seem to make reference to similar scenes in Jaws: People are seen underwater from below, with the bottoms of boats visible and the camera breaking through to the water's surface.

71Stanley M. Elkins, Slavery: A Problem in American Institutional Life (Chicago 1959). Compare, Lemisch, On Active Service, pp. 77-80. For Boorstin, see ibid., 74-77; for Bell and Hoffer, see ibid., pp. 56-58. In those bad times before the Sixties, when radicalism and utopianism were portrayed as mental aberrations, there was nonetheless a critical literature on the hostile portrayal of radicals and reformers. Particularly relevant as an antidote to Spielberg's later portrayal of the abolitionists is Martin B. Duberman, The Antislavery Vanguard: New Essays on the Abolitionists (Princeton 1965). The general theme of anti-radicalism is dealt with in my On Active Service in War and Peace. And Eric Foner ("Hollywood Invades the Classroom"), writing about Amistad in 1997, connects the film's hostility to the abolitionists with "today's cynicism about broad social movements."