“Harlem" has multiple meanings: It is at once a geographical space; a neighborhood of constantly changing ethnicities, nationalities, and languages; the birthplace of a famous cultural and artistic movement; an economic environment where poverty and affluence exist on the same streets; a site of black resistance and history. For many years, it has not been the largest black community in the country or even in New York City. At the height of the Harlem Renaissance in 1927, W.E.B. Du Bois complained that stereotypes all too frequently distorted the image of this community. "It is not chiefly cabarets, it is chiefly homes; it is not all color, song and dance, it is work, thrift and sacrifice," Du Bois stated. If Harlem is to be "bribed and bought by white wastrels, distorted by unfair novelists and lied about by sensationalists, it will lose sight of its own soul and wander bewildered in a scoffing world. Yet Harlem continues to be the foremost home of the racial imagination of black urban America.

In October 1995, the largest mass mobilization of African Americans in U.S. history took place—the Million Man March. Conceived by conservative black nationalist Louis Farrakhan, head of the Nation of Islam, the event was billed as a "Day of Atonement." Curiously, the march organizers said little about the Republican-controlled Congress's assault against affirmative action, civil rights enforcement, and social welfare policies then well underway. Instead, a program of racial self-help, spirituality, and patriarchy was emphasized. The Million Man March was followed subsequently by the Million Woman March, which brought several hundred thousand African-American women to Philadelphia and was also oriented around a culturally conservative program. Both marches generated broad-based enthusiasm and support within the national black community, although a significant number of black feminists, gay and lesbian activists, and other political radicals voiced their strong opposition to Farrakhan's leadership. What had given impetus to these public mobilizations was a widespread sense of crisis inside the national black community. Federal and state governments were abandoning public programs and social policies that directly benefited many black Americans. The mainstream African-American leadership seemed ineffectual in turning the situation around. Farrakhan subsequently attempted to construct a political formation, the African-American Leadership Council, to take advantage of the social momentum following these marches. The group quickly fell apart behind Farrakhan's controversial and separatist politics. Nevertheless, it was probably inevitable that other black activists would soon propose the call for a Million Youth March. The object of this new mass mobilization would be to highlight the highly problematic status of African American children and young adults throughout the United States.

Harlem Poster

African-American elected officials and civil rights leaders who had been outflanked by Farrakhan's Million Man March decided not to stay on the sidelines this time around. In Atlanta, when African-American youth activists began plans to hold a Labor Day weekend rally, mainstream organizations quickly backed the effort. A broad-based coalition emerged, including representatives from National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) youth chapters, the Urban League, the National Council of Negro Women, the Nation of Islam, Jesse Jackson's Rainbow Coalition, and many black churches. Rally organizers informed the press that their event would "center on political empowerment through voter registration and participation. However, a closer examination of the actual program of Atlanta's Million Youth Movement reveals an emphasis not on politics but on religion. The Million Youth Movement's announced platform called for a great "spiritual awakening" among African-American young people: "It is our goal to strengthen or re-establish our relationship with the Creator and allow spiritual direction to be at the nucleus of our lives." Participants in this spiritual enterprise must "make an Atonement to all those whom we have injured and in doing so, we can once again be at one with our Creator. " Economically, the movement's objectives included "instill[ing] the principles of collective work and ownership, harness[ing] our dollars into responsible spending and investment" and "entrepreneurship. Many of these priorities could have been comfortably accommodated in the program of the Christian Coalition, the Promise Keepers, or other mass evangelical, conservative formations. Few observers were subsequently surprised when barely 1,000 African-American young people came to the Atlanta rally. The mobilization's emphasis was too "mainstream" and clearly out of step with a generation defined by militancy of hip-hop popular culture.

Yet when other more militant black activists announced plans to hold a similar mobilization of African-American young people in New York City on the same weekend, expectations rose dramatically for an event as well attended as the rallies in Washington, D.C., and Philadelphia. With 2.4 million people of African descent living in the city's boundaries, black New York had long played a central role in the racial imagination of black America. A protest march championing the rights of young African Americans, built around a militant program of empowerment, could potentially inspire new movements throughout the entire country. And nowhere in New York City or the nation were black youth more "at risk" than in the neighborhood of Central Harlem, which was ultimately selected as the venue for the march.

Saying both "Harlem" and "black," for most African Americans, is being redundant. Central Harlem today is still overwhelmingly a non-Hispanic black urban center, with only a 12.5 percent nonblack population as of 1990. In the past three decades, however, the community has undergone major changes in its social and economic characteristics. In 1970, Central Harlem's population stood at 159,300; ten years later, it was 105,600, a one-third decline. By 1990, Central Harlem's population had dropped just below 100,000, but since that time, it has grown to just over 108,000. Although in recent years a number of black professionals, artists, and corporate executives have purchased and renovated a number of Harlem's gorgeous brownstones, most working-class and low-income residents have little in common with this affluence or privileged lifestyle. As of 1990, 30,600 residents lived on public assistance, such as Aid to Families with Dependent Children; another 8,900 depend on Supplemental Security Income.

Another major problem in Central Harlem is housing. Beginning in 1984, the city government began to place indigent families living in the city's hotel shelter system in Harlem. By the early 1990s, more than 4,500 homeless families had been relocated into Central Harlem. Simultaneously, the city failed to provide the necessary social services to support these families In 1993, Central Harlem had an estimated 40,500 households, of which the overwhelming number (39,300) were renters. Nearly 20 percent of all families lived in public housing. The median income for Central Harlemites living in rental housing was just $10,200

As in other major American cities in the past two decades, deindustrialization and the decline of jobs and social services had a devastating impact on black and brown children and young adults. According to the Children's Defense Fund, in 1987, the poverty rate for black children in New York City (52 percent) was more than double that for white children. By 1994, 62.1 percent of all African-American children and 75 percent of Latino children in New York City were born into poverty. Most children and adolescents growing up in low-income black households have only limited access to health-care services. About 20 percent of New York City's black and Latino population have no health insurance. Sixty-one percent of the uninsured children and young adults in this group are black

Major health indicators also clearly illustrate the social consequences of poverty, unemployment, and government neglect in Central Harlem. In 1991, infant mortality rates in the neighborhood were 15.3 per 1,000 live births, well above the city wide average (11.2). One out of seven infants was classified as a low birth-weight baby, nearly twice the citywide figure. The annual number of tuberculosis cases in the community per 100,000 (165.0) was over three times the city's rate. The annual number of AIDS cases diagnosed in Central Harlem per 100,000 (352.0) was double that for the city

A similar situation exists in economic life. Official unemployment rates for adults in Harlem is consistently estimated by officials at 20 to 25 percent. However, real labor-force participation rates are below 60 percent. This means that roughly 45 percent of all Harlem residents are outside of the paid labor force. Most Harlem businesses are not owned by blacks, and many still adhere to policies of employment discrimination. With immigrants from Korea and the Dominican Republic purchasing Harlem-based businesses during the past twenty years, large numbers of jobs have begun to disappear for young black women and men. In a survey of Korean merchants in Harlem and other black neighborhoods in New York City, sociologist Pyong Gap Min found that only 5 percent of all employees of Korean-owned businesses in the city are black. In Harlem, less than one-third of all employees at Korean-owned stores are black, whereas over 90 percent of their sales are to black consumers. The standard complaint is that "blacks don't want to work." In reality, there is fierce competition for low-wage employment in Harlem. At the McDonalds restaurant on 125th Street, about 300 people apply every month for jobs that pay $4.25 per hour. Overall, there are about fourteen job applicants for every low-wage job in Harlem's fast-food establishments

Nevertheless, these depressing statistics should not obscure the considerable strengths and resources within the Harlem community. There is an elaborate network of neighborhood-based social institutions: churches and mosques, social clubs, fraternities and sororities, business associations, tenants' groups, parents' organizations, small collectives of artists, writers, and musicians. There is also a long and very rich history of political and social protest that is well known to community residents. Thus, when prominent black nationalist Khallid Abdul Muhammad announced plans for a national Million Youth March to be held in Harlem sometime in September 1998, many Harlemites initially agreed that a carefully planned and well-organized protest should find significant support in their neighborhood.

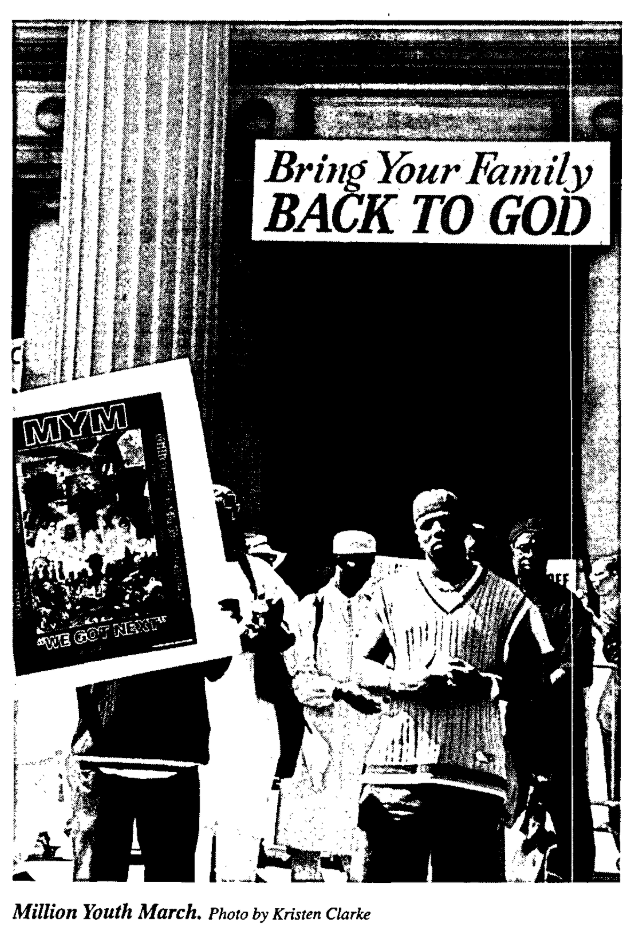

Million Youth March

To describe Khallid Muhammad as a "controversial" public figure would be a considerable understatement. Born Harold Moore Jr., in Houston, Texas, for two decades he worked his way up the hierarchy of the Nation of Islam, eventually becoming Louis Farrakhan's national spokesman. In February 1988, he was sentenced to three years in federal prison for using false information, including doctored tax returns, to obtain a home mortgage in Atlanta. Emerging from prison just as Farrakhan was attempting to become more mainstream, Muhammad's constant references to Jews as "bloodsuckers" who "deserved Hitler" was an embarrassment. Despite being demoted from the Nation of Islam's hierarchy, Muhammad continued to profit from his career of offensive hate speech, receiving as much as $10,000 per public engagement. Typical of Muhammad's public polemics was a 1997 speech to college students in California, where he declared the Holocaust to be a hoax and smeared Jews as "hooked-nose, bagel-eating, lox-eating, perpetrating-a-fraud, so-called Jews who just crawled out of the ghettoes of Europe.

Other notable characteristics of Khallid Muhammad, beyond his outrageous anti-Semitism, are his boundless egotism and shameless self-promotion. Muhammad's official biography, posted on the Million Youth March web site, declared that "the most distinct trait of this handsome black man, this lexical pyrotech, is that he speaks for the liberation and salvation of the black nation, the downtrodden and the oppressed." He applauded himself for possessing "a sense of humor that can have the audience bouncing in their seats with laughter" yet having the ability to "bring tears to the eyes of the toughest of his listeners." Muhammad listed among his many "accomplishments" serving as associate director of the Urban Crisis Center, a race relations consulting firm whose clients included U.S. Steel, Federal Express, IBM, AT&T, police agencies, and the federal government In his biographical profile, Muhammad also characterized his notorious speech at Kean College in New Jersey in November 1993 as one that "shook the racist Zionist, imperialist white supremacist foundation of the world." This hate speech is curious for a self-described corporate and government consultant on race relations. More recently, Muhammad made national headlines in June 1998 by leading armed members of two militant groups, the New Black Panther Party and the New Black Muslim Movement, into Jasper, Texas, to protest the white supremacist murder of a black man. Local residents and the victim's family denounced Muhammad for "exploiting their tragedy.

Many Harlemites who had heard of Muhammad knew he had recently purchased a magnificent nineteenth-century brownstone on Harlem's famous Strivers' Row, with an estimated market value of $1 million. With no office, Muhammad frequently conducts his business, according to New York magazine "out of the trunk of his $140,000 ocean-blue Rolls-Royce.

When Khallid Muhammad began preparations to hold his Million Youth March in Harlem, he largely ignored the community's middle-class community and local political leaders. He probably assumed that the socioeconomic conditions within the Harlem community were so severe that a natural constituency of grassroots supporters would quickly emerge. Bill Perkins, Harlem's city councilman, complained to the press that rally organizers had refused to consult anyone within his constituency. "Not me, not the clergy, not our youth leaders—nobody!" he emphasized. "It's like somebody coming into your house and just telling you he's taking over and throwing himself a party. Many local black leaders came out against the mobilization because of Muhammad's central role in it. "You can't build something off a person like Khallid Muhammad," stated New York Urban League president Dennis Wolcott. "I can't separate the march from the messenger." Others such as Harlem congressman Charles Rangel denounced Muhammad but encouraged participation, urging "church choirs to participate and Boy Scouts to show up in uniform, so that they might... take the hate that's been associated with this assembly and substitute it with love and concern. Even Louis Farrakhan, concerned about the negative repercussions that would occur if the Harlem rally degenerated into violence, sternly cautioned his former protégé against any behavior that might provoke the police. Farrakhan undoubtedly recalled the events of 1964, when a protest march against police brutality in Harlem erupted into violence between police and demonstrators. After several days of unrest, one person had been killed, 141 seriously injured, and over 500 people had been arrested, with property damage exceeding tens of thousands of dollars

It was at this moment that New York mayor Rudolph Giuliani came to Khallid Muhammad's rescue. The conservative Republican was first elected in 1993, defeating black liberal Democratic incumbent David Dinkins. During his tenure as the city's chief executive, a "cold war" had developed between the mayor's administration and the vast majority of the African-American community. It is fair to say that Giuliani was as widely despised among most blacks as he was praised and admired by the majority of the city's white electorate. The city administration curtly refused to grant a permit for the event in Harlem, and Giuliani repeatedly denounced the event as a "hate march." City officials would only allow the rally to take place on Randalls Island or in Van Cortlandt Park in the Bronx. Taking the city to court, U.S. District Court judge Lewis Kaplan ruled in favor of the march organizers, declaring that city officials had violated their constitutional rights to free speech and due process. A subsequent decision by a federal appeals court, however, restricted the rally to a six-block area on Malcolm X Boulevard and for a duration of only four hours Giuliani's opposition immediately generated unmerited yet widespread support throughout Harlem for Muhammad's efforts. Triumphant, Muhammad declared to his supporters that Giuliani was nothing but "an ordinary cracker" who had simply chosen "to ignore the law.

Demonstrators attending the Million Youth March, Harlem

However, with only days to go before the demonstration, local activists loudly complained that Muhammad's people still had done next to nothing to prepare for a mass public audience. No one had assembled the basic elements essential for a major rally, such as a stage, portable toilets, a sound system, and insurance bond. Regional coordinators of the 1995 Million Man March such as Sadiki Kammon, head of the Black Community Information Center in Boston, had not even been contacted by organizers of the New York event. NAACP youth leaders in Philadelphia, Washington, D.C., and other major cities declared to the press that they had "nothing to do with the event." Few plans had been made to coordinate buses to bring people to the rally site. Veteran Harlem politicians and activists began to suspect that Muhammad and his coterie of followers had no intention of mobilizing black youth around social issues. City councilman Perkins complained: "I've seen block parties that were better organized and planned. This has been the Khallid Muhammad show. It has nothing to do with the legitimate concerns and aspiration of young people. Nevertheless, in mid-August, lawyers for Muhammad maintained that the march was expected to draw 175,000 people. One reporter for the Financial Times (London) predicted on the eve of the march that it "is still expected to draw many tens of thousands of young people from as far away as Ohio and California.

On the morning of September 5, it was immediately apparent that the New York Police Department, not the marchers, was eager for a show of force. Over 3,000 police officers were assigned to the Harlem demonstration—a number easily large enough to handle 250,000 people. Barricades had been erected in the center of Malcolm X Boulevard, and dozens of surrounding streets were blocked off. The subway stations in Central Harlem were closed, with police using the underground sites for command posts. Police observers were stationed on the roofs of buildings overlooking the crowd. Police deliberately halted or diverted many people trying to cross intersections. Shoppers were kept from local stores; patients released from Harlem Hospital were denied permission to cross the barricaded street. Most of the people who were inconvenienced by these excessive police tactics were Harlem residents who had nothing to do with the march. It was like waking up and living in a military occupation zone.

The rally itself was something of an anticlimax. Only about 10,000 people attended the peaceful, four-hour rally. Police estimated the crowd to number only 6,000. Nearly all who came were not motivated by anti-Semitism, racism, or any sort of bigotry. This largely working-class and poor people's audience wanted to make a public statement concerning the challenges facing young African-Americans across the nation and especially in Harlem. Virtually no national figures were featured on the platform. Local Afrocentric educator Leonard Jeffries presented a demand for African-American reparations, and Al Sharpton delivered a political and entertaining speech. Unfortunately, there were no significant proposals about how to address the real problems confronting young adults and children within the black community.

At five minutes before 4:00 P.M., just before the rally was supposed to end, Khallid Muhammad finally took the stage and began to harangue the police officers surrounding the crowd, many now dressed in helmets and riot gear. Suddenly, a police helicopter swooped less than 200 feet above the crowd. As officers rushed the stage, Muhammad responded with irresponsible and inflammatory rhetoric: "If anyone attacks you . . . beat the hell out of them.... If they attack you, take their guns away, and use their guns in self-defense.

There was confusion, shock, and outrage in the unarmed crowd as a phalanx of police attempted to clear the stage and the streets. Activists tried to shield and protect smaller children in the crowd. Some of the crowd began throwing bottles at the police, and the cops responded by swinging their batons in discriminately. Several people yelled, "This is South Africa!" Fortunately, only the remarkable restraint shown by the vast majority of those who had come to the rally defused the situation. Within an hour, most of the crowd had been dispersed. Outraged Harlem political and religious leaders demanded to see Giuliani to protest the use of excessive police force in their community. Typically, Giuliani refused even to consider meeting with them. Attorney Dorothea Caldwell-Brown spoke for most black New Yorkers by observing that the mayor's actions "feed these young people to Khallid. He stands up and says, 'Look at how they treat you,' and here they come rushing in doing exactly what he says. Giuliani and Khallid are in concert… They need one another.

In Harlem folklore, the events of September 5, 1998, will probably be remembered as the "Million Cop March," where the integrity and civil liberties of an entire community were violated. Yet beyond the irresponsible misleadership of both Muhammad and Giuliani, the difficult challenges facing Harlem and the rest of black urban America still remain. But the history of our racial imagination provides real hope that new democratic movements for fundamental change may still be created.

1W.E.B. Du Bois, "Harlem," Crisis 34 (7) (September 1927):240.

2Larry Bivins, "Black Youth Marches Play Down Differences," USA Today, August 31, 1998.

3"Million Youth Movement Ten Year Action PlanAgenda," web site, available: www.millionyouthmovement.com, August 1998. 4.

4Community Board No. 10—Manhattan, Statement of District Needs, published by the City of New York, 1996.

5Ibid.

6City of New York, Rent Stabilized Manhattan: An Apartment Building Income and Expense Profile, compiled by Ted Fields, City of New York Rent Guideline Board, January 1997.

7Phyllis Y. Harris, "Impact of Social Factors on Health," in June Jackson Christmas, ed., Growing Up . . . Against the Odds: The Health of Black Children and Adolescents in New York City (New York: Urban Issues Group, 1997), pp. 15-18.

8Phyllis Y. Harris and June Jackson Christmas, "Profiles of Three Black Communities," in Christmas, ed., Growing Up . . . Against the Odds, pp. 19-26.

9Jonathan Kaufman, "Help Unwanted: Immigrants in U.S. Refuse to Hire Blacks in Inner City," Asian Wall Street Journal, June 7, 1995.

10Henry Goldman, "Judge: Can't Bar Million Youth March Permit," Philadelphia Inquirer, August 27, 1998.

11"Dr. Khallid Abdul Muhammad Biography," web site, available: www.millionyouthmarch.com.

12David M. Halbfinger, "Behind Hate Speech, an Enigma," New York Times, August 31, 1998.

13Peter Noel, "Blood Brother," New York 31 (34) (September 7, 1998):25.

14Goldman, "Judge: Can't Bar Million Youth March Permit."

15Henry Goldman, "N.Y. Youth March Is On, But Are Organizers Ready?" Philadelphia Inquirer, September 2, 1998.

16Basil Wilson and Charles Green, The Struggle for Black Empowerment (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1992), p. 20.

17Patricia Hurtado, "Marching Order/Court Places Restrictions of Six Blocks and Four Hours," Newsday, September 2, 1998.

18Abby Goodnough, "Youth March Organizer, Celebrating Ruling, Taunts Giuliani," New York Times, August 28, 1998.

19Raymond Hernandez and Monte Williams, "Days Before Harlem Youth Rally, Little Effort to Draw Big Turnout," New York Times, September 3, 1998.

20John Labate, "Confrontation Flares Over Million Youth Solidarity March," Financial Times (London), September 4, 1998.

21Dan Barry, "Rally in Harlem Ends in Clashes with the Police," New York Times, September 6, 1998.

22Somini Sengupta, "Voicing Anger at a Day Turned Upside Down," and Mike Allen, "Some Experts Say the Rules on Rallies Were Ignored," New York Times, September 7, 1998.