I would argue that it makes some sense that in a time of elusive, yet emergent, cosmopolitanized identities, of sweatshop- and shantytown-spawning multinational corporations, of entry-level service-sector-only employment opportunities in Big City, U.S.A., an anthropologist attempting to write about the here-and-now of post-civil rights urban America might find it fruitful to begin, of all places, at that quintessential locale of global sameness called McDonalds.

That mythical space where identical memorized greetings ("Welcome to McDonalds, may I take your order, please?"—a capitalist command in the guise of a question) are offered up time and again by uniformed, minimum-wage-earning, secondary-labor market workers, each with that exact same perky yet disingenuous smile etched on an otherwise disgusted face. McDonalds, where the mass-produced logic of late capitalism duplicates itself, with ever-so-minor modifications, on nearly every strip mall or highway or street corner or college campus across the country. And most directly, the place where this particular story begins. On that fine line of evidential limbo separating the illuminatingly "ethnographic" from the merely "anecdotal." A line hardly different, conceptually speaking, from the one I was waiting in at a McDonalds restaurant on 125th Street when I first met Dexter, a young black male customer arguing with Pam, the young woman trying patiently (but unsuccessfully) to take his order, please.

Dexter, dressed in white-and-black fatigues, held in the palm of his right hand a colorful coupon, in exchange for which he was supposed to receive a $.99 Big Mac in every part of the city (so read the fine print) "except the borough of Manhattan," where a Big Mac— with this same coupon—would cost him $1.39 instead. Well, hearing Pam repeat that important distinction, Dexter was outraged that he was being forced to pay $1.39 for his Big Mac sandwich. With only a dollar and a dime in his outstretched left hand (the $.10 was "for tax," he declared several times), Dexter made his case: "This is Harlem," he said, "not Manhattan! If they meant Harlem, if they meant Harlem, they should have written Harlem! Harlem is not Manhattan! So, I'm paying $1.10 for my Big Mac." Once Dexter finished his spiel and clunked the money on the counter, other customers lined up in front of cash registers all around him (along with the brown-and-red costumed McDonalds staff at work on the other side of the long silver counter) mostly chuckled, giggled, and shook their heads incredulously at his argument, an argument that, in its unabridged iteration, took over ten full minutes to play out. But Dexter didn't mind their smirks; he was adamant, determined—even though his half-smiling face and exaggeratedly playful body language clearly, if only indirectly, indicated he knew full well that Harlem was smack dab in the borough of a Manhattan Island where Big Macs (as a function of, say, higher-priced rental space and property taxes) simply cost $.40 more than in any other part of the city. On this particular day, however, Dexter would not and did not leave that crowded McDonalds restaurant until Pam, poised and patient behind her cash register, reluctantly snatched his dollar (and his dime) and handed him a Big Mac sandwich to go—a paper-bag-covered burger he was munching on greedily as I jogged out to catch up with his much heftier strides in the fast-food restaurant's wet and slippery parking lot.

Dexter's analysis served as the central frame and organizing principle through and around which I would toil for close to a year and a half. I was doing an ethnography of social solidarity in Harlem, but Dexter had hit on the complicatedly symbolic boundaries that I had to engage—before anything else. A Harlem in Manhattan, but then again not quite bound there. A Harlem thought (by both those who reside there and many more who wouldn't dare) to be a kind of world apart; a living, breathing space whose semiotic significances inform the boundaries between the supposedly black and white worlds of New York City. A place where the objective conditions of people's existence and their subjective responses to those conditions illustrate the elaborate relationships between structural marginalization, cultures of poverty, and individual agency in a postindustrial context rife with all manner of lucrative underground economies and devastatingly "savage" inequalities.

Hearing Dexter argue with Pam about the distinctly separate location of Harlem vis-àvis Manhattan, of the impossibility of reducing Harlem to its geographical location exposed my own facile assumptions about what—ethnographically speaking—made up Harlem and its borders.

According to the New York State Visitor and Convention Bureau, Harlem has the highest name recognition of any neighborhood in the entire state of New York, and for my argument, this tiny bit of trivia is quite substantial: the most famous neighborhood in the nation's most famous city is Harlem! It is known the world over. But for those who live there, who live with (and even off) that notoriety, what does Harlem mean? What and where is Harlem, really? One of my first ethnographic tasks, as I saw it, was to address just that: how field sites like Harlem, with reified names that far precede and exceed the stretches of land they designate, operate beyond easily demarcated and circumscribed ways; how places like Harlem are discursively and subjectively mobilized toward various ends; how a volitional rendering of place impacts and informs people's racialized identities and class(ed) positionalities.

At right: Harlem kids

It is possible to fall back on Benedict Anderson's notion of an imagined community as a means of vouchsafing access to arguments about the mystical constructedness of place and space and their impact on people's social identities. In Anderson, specific relations between literacy and industrialization helped spawn the discursive and extradiscursive foundations upon which contemporary nationalisms (and nation-state solidarities) were first made to stand. With the advent of mass-produced, print-culture capitalism, citizens became better able to imagine a connection to relatively unknown others across the daunting obstacles of both space and time. Andersonian assessments of created communities can speak most loudly and directly to a Harlem that not only uses various discursive modes to shore up the social and spatial parameters of its imagined home but also (and more important, I choose to share with an anthropologist who think) a Harlem possessing the uncanny to resituate itself in another time and space entirely. In Dexter's case, this relocation carries Harlem out of the borough of Manhattan altogether and into an area that he claims "is not Manhattan." Any ethnographic work conducted in Harlem, on the hard-core issues of the day (deindustrialization and its links to urban unemployment, institutionalized racism, welfare-to-workfare reforms, transgenerational cultural pathologies, and so forth), must take Dexter’s cartography seriously.

This idea of “Harlem,” snuggled neatly within quotation marks, operates as a kind of place apart, functions as a geographic and iconographic space talked about with an almost mythical distinction, with an air of extraspecial signification. And an ethnographer working here must consciously and carefully wade through the mounds of excess meaning connected to a space imagined from within and without, by those who would use its name to either (1) index a sense of belonging or (2) scream at a black threat seeping down from uptown. Before writing a single word about linkages between class stratification and racial identification in Harlem I first had to peel back the multilayered understandings of place and its connection to identity. Indeed, these understandings cloud and obstruct any attempt at writing race, class, and culture in a wonderfully mediated field site like Harlem, a Harlem where preconceived and continually reconfigured notions of “the real” simultaneously and contradictorily obscure yet illuminate what is most consequential about the place itself.

***

One of the first roads of inquiry into a quotation-marked-off Harlem has to do with Harlemites and their varying and prescient articulations of this place’s taken-for-granted-ness—that is, those articulations they choose to share with an anthropologist who asks. Danielle, a thirty-seven-year-old elementary school teacher who lives on a tree-lined street off Adam Clayton Powell/Seventh Avenue, just three blocks from where she teaches third graders, says that the “Harlem” she knows is nothing if not in a league all by itself:

Danielle: Harlem is special. It is a special place. I’ve been here fourteen years, and I know that I am lucky to be here. Because there is only one Harlem in the whole entire world. There is just one. So I’m lucky to be here, you know, to be making a way here, because it’s easy not to make it. And there are plenty of people in Harlem who know that, you know, who live that. Who aren’t as lucky as me. To be here and happy with their lives.

Asia, twenty-two, a third-generation Harlemite who lives on 104th and Lexington and works with Pam at the McDonalds restaurant where I first heard Dexter extract “Harlem” from Manhattan Island, offers a slightly different spin on Harlem’s particularity:

Asia: Harlem to me is like the real nitty-gritty. Like hard and real and dangerous. I lived in Brooklyn before, for like two years, and my oldest sister lives in Long Island with her boyfriend, but none of those spots is like Harlem. They just don’t feel like Harlem.

John: What does Harlem feel like?

Asia: I don’t know, but no other spot feels like it. I could close my eyes and you could take me anywhere and if you bring me back to Harlem, I would say, I’m back home. ‘Cuz no place sounds and smells like here. Or is real and, I don’t know, nitty-gritty, and rough and real like it. I can’t really explain it. But I know I’m right.

Harlem barbeque

Both Danielle's "special place" Harlem, the only one of its kind "in the whole entire world," and Asia's almost tactile, yet inexplicable "nitty-gritty" Harlem, a neighborhood that no other place quite "feels like," are significantly recurring strands of a common argument running through contemporary discussions about Harlem's embraceable distinctiveness. There are, in fact, many people (Harlem residents or not) with a highly vested interest in what this peculiarly "special" place looks like and reads like, how it is to be seen and represented.

People have a stake in the space's definition; they defend and police its meaning with a protective vengeance. Refracted through, say, social hierarchies, this place called "Harlem," this Harlem idea, can work as an important template for thinking not just about one's connections to place but also about one's relationships with others.

Cynthia, twenty-eight, a part-time security guard for an office building on 125th and Frederick Douglass/Eighth Avenue, was born in Virginia and has lived in New York City for the last twelve years.

Cynthia: When I see Harlem, you know, when I look at it, I don't see any welfare or crime or drugs. None of that nonsense. This is the Mecca. I mean, I don't see beggars and homeless people on the street. Or begging by the bank. When I see Harlem, I see, like, a perfect picture. It is just beautiful. That is Harlem.

Cynthia uses this "beautiful" version of Harlem to justify her criticism of what the social science literature would call "the underclass"—a group that is, according to Cynthia, tarnishing the shiny legacy of this "Mecca" of black America and, therefore, must be denied access (at least symbolically) to its most-hallowed name. Cynthia's no-"nonsense" Harlem is asserted to the exclusion of stereotypical representations of urban America, stereotypes that foreground poverty, criminality, and drug use as emblematic and even constitutive of the place itself. Contrary to these many negative images and depictions of urban America, Cynthia's Harlem is a place "where you can just have fun and feel free. No racism and things like that. No. Just good lives. Like what it used to be."

Carl, thirty-one, more securely in the so-called black middle class than Cynthia, is a finance lawyer who has lived in Harlem for some fifteen years now. He grew up with "dirt-poor, broke parents" who moved here from the Caribbean in the 1950s, before he "was close to being born." Waving to a waitress as he whips out a credit card to cover our fried chicken lunch at a new soul-food spot in midtown Manhattan, Carl offers a picture of "Harlem" that locates its validity and reality even more specifically in a past that, as Cynthia put it, "used to be":

Carl: Harlem is history. And I don't know a lot about all of it. I'm just starting to really know it. I've been focusing on my stuff, you know. I've seen some tours. The grange. Not many, but that is Harlem. It is history, the history of an entire people. Sure there are bad things, but Harlem isn't just that. Troublemakers here are people who don't know what Harlem should be like. That's all they've seen, you know, the nastiness, the poverty. They haven't seen better and don't know no better. Maybe if they knew more of that history, you know, they would try to fly right.

Ms. Joseph, fifty-five, a Seattle native who made collegiate pit stops in Southern California and Omaha, Nebraska, before settling into a Harlem brownstone with her architect husband some twenty years ago, considers Harlem "the center of the world."

John: Is it a bad place to live?

Ms. Joseph: It ain't bad at all. I mean, no worse than any place else, right? The crime and stuff is not Harlem. If anything, that is gonna make Harlem not be Harlem anymore. You know?

John: No. What do you mean?

Ms. Joseph: The more crime and violence and drugs ... means we got less and less of Harlem every day. Every time somebody gets killed or something, Harlem is dying, too. That kind of thing is not Harlem. Its just killing Harlem—little by little, bit by bit. It takes away from Harlem, like as if one day we'll wake up and there won't be any Harlem anymore and people would be looking around asking, "What happened? what happened to it?" It would just be gone.

Ms. Joseph's Harlem, to be Harlem at all, presumes the exclusion of violent death and crime. It is a Harlem that flies in the face of vicious murders and drugs, the kinds of actions that don't just kill people, Ms. Joseph argues, but kill place as well.

Ms. Joseph: I just get tired of all of it. Like when, when, when Jeffrey's sister—my husband, Jeffrey—got held up right around the corner, that wasn't more than a month ago. I don't usually have no problems here. I see the people doing what they doing, but I usually just go about my business. I go right past them like they weren't there. Because for me, they are not there. I don't see them. They just like ghosts: you know, the drug dealers and, and, and things. These people aren't part of my community. They aren't from here.

John: Where are they from, do you think?

Ms. Joseph: I mean, maybe from the Bronx, or some other state, but even if not, they still ain't from Harlem. Even if they from here, if they live here. Maybe you could say they from upper Manhattan, or from 155th Street, but that don't mean they from Harlem. That just mean they live on 155th Street. Not Harlem. Not if they doing that kind of stuff. Harlem don't want them.

Ms. Joseph, too, has neighbors, like Cynthia's "beggars at the banks," who may share the same physical surroundings but who are excluded from a valid social place. Socioeconomic status functions as one of the criteria used to sift through the social landscape and separate the legal/legitimate form of social citizenship from the illegal/illegitimate. Just as Ms. Joseph and Cynthia can look down the socioeconomic ladder at undesirables who don't belong, some "Harlemites" look up the social ladder to challenge their upper-class race mates' rights to call "Harlem" home.

"Harlem is what I know," says Sheila, twenty-seven, unemployed, and trying to get into a GED preparation program. We are walking and talking on Frederick Douglass Boulevard as she points out places she's lived in, or been to, or heard tall tales about.

Sheila: The people I know, the people who have to work and struggle to make it every day, we here and we real. Real life. There are people who want to come in here and don't have a clue, but they come cause it's cheap rents and stuff, and they want to be here and act like they better than any of us, but they really need to be someplace else. They not from here, not belonging here. They the ones that think they can do whatever they want up here, that they can do whatever they want and won't nobody do nothing. But that ain't true. And most of them gonna learn, too.

For Sheila, as for Cynthia and Ms. Joseph, there is vast space separating residency from really belonging. David, Sheila's twenty-year-old on-again, off-again boyfriend, talks emphatically about where Harlem "is really at":

David: Harlem is from the left side to the right side of Manhattan. Uptown. Period. Good and bad. Take it or leave it. Harlem is like a ghetto like everywhere else, where black people live and work and play and die. People kill each other and they go to church. And they, sometimes, some of them work, and some of them stay home and do drugs and wait for a welfare check and don't do nothing else except watch TV and movies. All of that is what is going on here every day. That's what's happening.

To hear David tell it, listening to him capture the series of divergent experiences during any average, ordinary day in a Harlem "where black people live," a "ghetto like anywhere else" (no more or less special and specific than other any neighborhood), we get a representation of Harlem's value as a sociological idea that becomes more and more complex and compelling. David's "Harlem" shows the ease with which a globally recognized Harlem-concept (that most famous neighborhood in all the United States) slides effortlessly back and forth between (1) Black "Mecca" hyperspecificity and (2) an easy collapsibility into a stereotypical representation of contemporary black urbanity. Ms. Joseph's explicit exclusion of a 155th Street resident/drug dealer/crack addict from her pristine Harlem and Sheila's dismissal of the Buppie without-"a-clue" pragmatists who think they belong but really don't both speak to the subtle kinds of ways in which any community and its residents, not just those in Harlem, apply the litmus test of desirability to define locals/residents who are supposedly jeopardizing, in different ways, the sanctity and solidity of the collective social space.

All the understandings of this place called "Harlem" (and there are many more besides the few offered here) lead to one central point: that the importance with which "Harlem" is imbued does not negate its status as a stand-in for black America. Harlem can be both "special" and "ordinary" at one and the same time. But what does this mean for an anthropologist trying to make sense of the place itself? What should the ethnographic gaze behold when it casts its eyes upon a quotation-marked-off place like Harlem?

***

To answer this I want to backtrack a bit, to a genesis story of sorts. The early strands of the discipline's lineage are debatable, but in one origin story of anthropology's early years, there was an armchair. And in it sat the ethnologist, a person who supplied an analytical eye (or two) to the raw materials of others' observations. It was someone else who did the ethnographic dirty work (say, a traveling merchant with a trusty journal or a proselytizing missionary, diary in hand), and the masterful ethnologist pulled these sordid and motivated tales together into some universally explanatory schema. But this armchair brand of anthropological inquiry gave way as the discipline flung itself full swing into an institutional and accredited distinction between its methodologically honed scientific empiricism born of firsthand participant-observation versus what was considered the shoddy, grossly unscientific and relatively inadequate writings of nonanthropologists. The anthropologist's expertise came from a scientifically trained vision that could pierce through the many details of a seemingly incomprehensible culture and provide a scientific formula through which to make sense of it all—be it evolutionism, structural-functionalism, transmissionism, structuralism, cultural materialism, and so on.

The primitive's village became the site wherein rested the anthropologist's authority. A long visit to that "Promised land" as Roger Sanjek put it, coupled with a mastery of the native language, meant a scientifically holistic view of an entire people. But there is really so much more behind the scenes.

As many have argued, this perfect, scientistic picture of cultural critique elides as much as it illuminates. First of all, the "field" wasn't as isolated, discreet, and monolithic as (explicitly or implicitly) assumed. In fact, this reified field site, the empirical ground upon which the discipline stood, was even said to be a kind of fabricated region, a made-up space—and in more ways than one. A fabrication that resonates most directly with Dexter's attempts at dislodging Harlem from its Manhattan moorings. (Or ever better, with Columbia University's pamphleteering two-step that maneuvers its thousands of dollars and tons of material in and out of "Harlem" into the sunnier site of "Morningside Heights"—except, of course, when recruiting students of color to its "home in Harlem."

The anthropologist can be said to create boundaries where there are none, to force and forge distinctions between here and there in an effort to pin down and circumscribe the space within which fieldwork will take place. In order to see "the other" better, the ethnographer has traditionally had to condense and downscale the amount that was to be seen. And that downsizing has often meant an overly rigid gerrymandering of social space. But for the anthropologist to see this in person, of course, was not the ultimate point, and the published monograph distilled the anthropological gaze into a narrative form that, according to Jim Clifford, solidified the ethnographer's unassailable authority while, as Johannes Fabian puts it, freezing the other into a perpetual past distinct from the Western world's much more modern present. And so, in that overly surefooted discursive field, a moment—a meta-ethnographic moment— opened up that would allow, using the tools of literary criticism, for ethnographic texts to be "looked at" as well as "looked through" to some overly reified and supposedly transparent other.

Critiques of the ethnography as a text abound. What ethnographers see and what they think they get are both fair game for critical engagement. Ethnographies, it is argued, are not just pure and unadulterated reflections of what has been observed but rather are crafted and constructed worlds that stand in for the jumbled reality from which often indecipherable field notes are alchemized into realist narrative accounts. And if that was true in the past for Bronislaw Malinowski's Western Pacific or Margaret Mead's Samoa (or, more self-consciously so, for Zora Neale Hurston's Eatonville), how much more so is it now? And even still, in a place like Harlem, "that Mecca of black America," the New World center of the fabled African diaspora, "the queen of all Black belts." And how much more so in-the-here-and-now of the late twentieth century and its new-fangled transnational trade agreements, international immigration shifts, and First World deindustrialization?

The head-in-the-sand, cultural-village anthropologist of yesteryear was a fiction (Clifford calls it an "allegory") created to, among other things, justify the discipline itself. Anthropologists must look up, out and beyond what easy borders we are quick to create, beyond the arbitrary parameters we translate into and project onto our anthropological field sites. We must open up the ethnographic view to include international connections that link places through the flow of never-ending and mobile peoples and capital. And many theorists are arguing for just such an opening of the field site—for looking past our assumed, hard-and-fast boundaries. Jelan Paige asks for an ethnographic engagement with black people and cultures that takes mass media stereotyping seriously as obstructions to any ethnographic understanding of African Americans. Faye Harrison lobbies for an opening up of ethnographic inquiries and field sites into an analysis of how television, radio, and motion picture images inform and cocreate our perceptions of the world. Arjun Appadurrai pleads for a transnationalized, transculturally savvy understanding of societies that links the locally specific to its global context. Where they all agree is in the understanding that field sites must be opened up into other sites (even "multisited"). But how far open? And where does the opening end? Where does it close? Should we open the anthropological gaze into just other nearby neighborhoods? Into contiguous nations? Into a black Atlantic paradigm that recognizes the analytical bankruptcy of the nation-state's borders as valid cutoff points for social and cultural analyses? Even into Wallersteinian-influenced world-systems theories that ask for center-periphery models of the entire planet's players on the global stage? A Derridean invocation of signification means opening "the field" up into textuality and intertextuality, all of which could be interpreted with Geertzian-thick descriptions galore. I would say yes to these recommendations. But I want to go further, especially in a place like "Harlem." I want to argue for an opening up of the field site (as politically irresponsible as it might sound at first blush) into the ethnographic land of make-believe, into the ethnographic imaginary, where fact and fiction, true and false, chip away at the walls of demarcation that separate their shadowing and mutually constitutive worlds. An opening up into the ideas we hold and are taught to have about places like Harlem, places whose boundaries are magically malleable and whose people are stereotypically assumed.

***

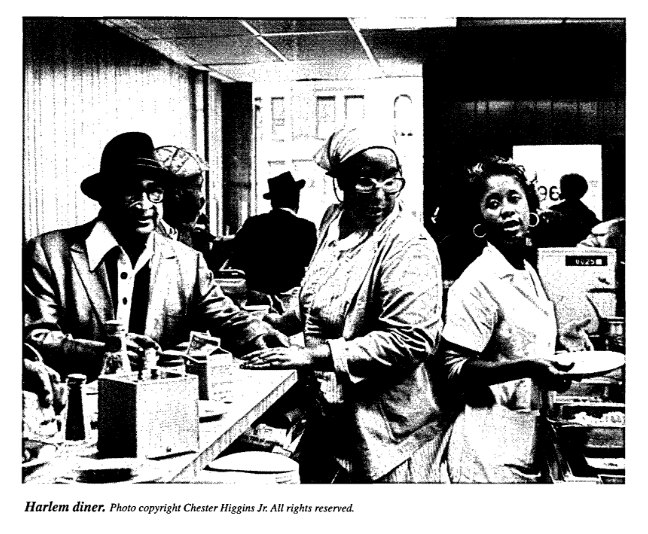

Harlem diner

Chuck, twenty-five, a part-time student at a community college in the middle of 125th Street, says that "Harlem is like a person you got to take the time to know. When you know Harlem, she will treat you right. And if you don't take the time to, she won't. She'll lie to you and you'll be stupid enough to believe it. Cause people do everyday. They think Harlem is this but it ain't. It's that. And they don't get it. And won't believe you when you tell them they wrong." Chuck's decidedly gendered Harlem is a place that, first and foremost, misrepresents itself. It is a Harlem that might be said to make itself up as it goes along. A Harlem able to fictionalize itself and keep its pursuers off its hidden tale.

And it is, of course, the artisans who are the first ones there in that make-believe made-up land of a camouflaged, quotation-marked-off "Harlem" that "is not Manhattan." The artists. Particularly, the actors: the professional pretenders. The ones trained to recognize the inevitability of that constitutive intermingling of truth with falsehood when it comes to location and identity. As such, an ethnography of the cinematic is in order. Ethnographicus cinematicus. In this case, movie star Denzel Washington's carefully measured advice to rapper-turned-actor Will Smith—and the approach Denzel thinks Will should take to his role in the film Six Degrees of Separation (1993), where Smith plays Paul Poitier, a black, homosexual, Walter Benjamin-quoting con artist who lies his way into the home of a wealthy art dealer on Manhattan's Upper West Side by falsely claiming to be Sidney Poitier's son. Pretending to be the child of a black film icon, Paul is indeed Harlem's prodigal, if still unclaimed, offspring. In fact, Harlem, as a very character in the film, is right there (off-camera, of course) portentously in the background all the while—playing itself and providing the distant, aerial-shot backdrop to this tale of class-based posing, passing, and performativity. The separation point, the borderline, is an Upper West Side apartment of gullibility (an apartment off Central Park no less, that last landscaped border post protecting a posh middle-classness of double Kandinskys and English hand-blasted shoes from the presumed anarchy raging uptown).

But Six Degrees is based on only one real story made into a stage play and then adapted to the silver screen. The other real story, the other real-life story, has Denzel Washington, another icon, the next Sidney Poitier (some say), who's played many a Harlemite onscreen, passing on some acting wisdom to Will Smith: an arguably homophobic admonition that Smith not, as called for in the script, kiss a white, male actor on-screen; that Will feign the two kisses (one set in a Boston studio apartment, the other in a stage coach riding through that very same Central Park border land) Denzel maintains that Will should obstruct the kiss from view, fake it (by turning his back away from the screen/the audience and pretending that he and his white, male costar's lips touch on the other side of the back of his head). Smith must conceal the act, Denzel argues, because the black audience wouldn't be able to read that action as just made up; wouldn't see the kiss as acting; couldn't distinguish between the "real" and the "make-believe" of the thing. Denzel's rather patronizing assessment of black people's mass-media decoding capabilities is a provocative and interesting (however condescending) model, I believe, for looking at an ethnographic field site, especially when that site is a place like Harlem, a place where the line between fiction and nonfiction, as people talk about the neighborhood they know, is fuzzy indeed. Maybe Denzel's point helps to unpack the truths and fictions of Cynthia's beggarless and Ms. Joseph's drug-dealerless Harlem, U.S.A. What if, Denzel's homophobia and provincialism notwithstanding, people in that black audience he talks about can't tell the difference between fact and fiction because they recognize the often equivalent effects of the shadow and its act. That is, they know a world where stereotyped unrealities have an impact on people's lives that disproves any easy argument for the power of some supposed real over the unreal. Indeed, the unreal assumptions about places like Harlem (assumptions that impact the decisions, say, of big businesses about whether to move there or that inform where people choose to eat, shop, and so on) have been powerfully determining factors in the very real lives of the people who reside there.

Moreover, in a place like Harlem, "What is 'real'" (what is Harlem, really?) becomes a tricky question. Margaret, thirty-three, goes to school at City College, fifteen minutes south, by foot, from where she lives with her mother, three sisters, a brother, and two nephews in a two-bedroom apartment. She offers yet another take on Harlem, a take very real in its unreality:

Margaret: Harlem is no poverty, no immigrants, no trash on streets. Harlem is not any of that. That is not what I think about. I don't. I don't at all. Harlem is nothing bad. Nothing bad like that. And nobody can't tell me any different. Nobody.

What people think about Harlem and its boundaries, whether true or not (even a trash-free Harlem xenophobically and unrealistically peopled, as Margaret asserts, without immigrants and the poor), has true enough consequences, especially when depictions of blacks, in or out of Harlem, carry the stereotypes of many generations on their backs As Dexter put it: "They come up here, they don't know us. Think they know Harlem; they think they do, but they don't. They could never know us. They just think they know us from what they been taught from TV and shit for all these years. Nothing but lies."

1This article was written for and presented at Columbia University's Institute for Research in African American Studies during the spring of 1998 as part of a semester-long series on the Harlem community. This is an excerpt from a longer piece entitled "White Harlem: How to Do Ethnography with Your Eyes Closed."

2I know from my own recruitment that Columbia University is strategic about when and where it mobilizes the quotation-marked-off notion of "Harlem" in its recruitment and admissions literature.

3Will Smith has retold this story about Denzel Washington's advice many times, both in TV interviews and in print.

4Ethnicity falls out of this equation, especially as ethnic differences are strained against the power of black overdeterminism in Harlem.